Grimdark Magazine Issue 24 PDF

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The University of Chicago Tears in the Imperial Screen

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO TEARS IN THE IMPERIAL SCREEN: WARTIME COLONIAL KOREAN CINEMA, 1936-1945 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF EAST ASIAN LANGUAGES AND CIVILIZATIONS BY HYUN HEE PARK CHICAGO, ILLINOIS AUGUST 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF TABLES ...…………………..………………………………...……… iii LIST OF FIGURES ...…………………………………………………..……….. iv ABSTRACT ...………………………….………………………………………. vi CHAPTER 1 ………………………..…..……………………………………..… 1 INTRODUCTION CHAPTER 2 ……………………………..…………………….……………..… 36 ENLIGHTENMENT AND DISENCHANTMENT: THE NEW WOMAN, COLONIAL POLICE, AND THE RISE OF NEW CITIZENSHIP IN SWEET DREAM (1936) CHAPTER 3 ……………………………...…………………………………..… 89 REJECTED SINCERITY: THE FALSE LOGIC OF BECOMING IMPERIAL CITIZENS IN THE VOLUNTEER FILMS CHAPTER 4 ………………………………………………………………… 137 ORPHANS AS METAPHOR: COLONIAL REALISM IN CH’OE IN-GYU’S CHILDREN TRILOGY CHAPTER 5 …………………………………………….…………………… 192 THE PLEASURE OF TEARS: CHOSŎN STRAIT (1943), WOMAN’S FILM, AND WARTIME SPECTATORSHIP CHAPTER 6 …………………………………………….…………………… 241 CONCLUSION BIBLIOGRAPHY …………………………………………………………….. 253 FILMOGRAPHY OF EXTANT COLONIAL KOREAN FILMS …………... 265 ii LIST OF TABLES Page Table 1. Newspaper articles regarding traffic film screening events ………....…54 Table 2. Newspaper articles regarding traffic film production ……………..….. 56 iii LIST OF FIGURES Page Figure. 1-1. DVDs of “The Past Unearthed” series ...……………..………..…..... 3 Figure. 1-2. News articles on “hygiene film screening” in Maeil sinbo ….…... 27 Figure. 2-1. An advertisement for Sweet Dream in Maeil sinbo……………… 42 Figure. 2-2. Stills from Sweet Dream ………………………………………… 59 Figure. 2-3. Stills from the beginning part of Sweet Dream ………………….…65 Figure. 2-4. Change of Ae-sun in Sweet Dream ……………………………… 76 Figure. 3-1. An advertisement of Volunteer ………………………………….. 99 Figure. 3-2. Stills from Volunteer …………………………………...……… 108 Figure. -

Scheherazade

SCHEHERAZADE The MPC Literary Magazine Issue 9 Scheherazade Issue 9 Managing Editors Windsor Buzza Gunnar Cumming Readers Jeff Barnard, Michael Beck, Emilie Bufford, Claire Chandler, Angel Chenevert, Skylen Fail, Shay Golub, Robin Jepsen, Davis Mendez Faculty Advisor Henry Marchand Special Thanks Michele Brock Diane Boynton Keith Eubanks Michelle Morneau Lisa Ziska-Marchand i Submissions Scheherazade considers submissions of poetry, short fiction, creative nonfiction, novel excerpts, creative nonfiction book excerpts, graphic art, and photography from students of Monterey Peninsula College. To submit your own original creative work, please follow the instructions for uploading at: http://www.mpc.edu/scheherazade-submission There are no limitations on style or subject matter; bilingual submissions are welcome if the writer can provide equally accomplished work in both languages. Please do not include your name or page numbers in the work. The magazine is published in the spring semester annually; submissions are accepted year-round. Scheherazade is available in print form at the MPC library, area public libraries, Bookbuyers on Lighthouse Avenue in Monterey, The Friends of the Marina Library Community Bookstore on Reservation Road in Marina, and elsewhere. The magazine is also published online at mpc.edu/scheherazade ii Contents Issue 9 Spring 2019 Cover Art: Grandfather’s Walnut Tree, by Windsor Buzza Short Fiction Thank You Cards, by Cheryl Ku ................................................................... 1 The Bureau of Ungentlemanly Warfare, by Windsor Buzza ......... 18 Springtime in Ireland, by Rawan Elyas .................................................. 35 The Divine Wind of Midnight, by Clark Coleman .............................. 40 Westley, by Alivia Peters ............................................................................. 65 The Headmaster, by Windsor Buzza ...................................................... 74 Memoir Roller Derby Dreams, by Audrey Word ................................................ -

The New Cosmic Horror: a Genre Molded by Tabletop Roleplaying Fiction Editor Games and Postmodern Horror

315 Winter 2016 Editor Chris Pak SFRA [email protected] A publicationRe of the Scienceview Fiction Research Association Nonfiction Editor Dominick Grace In this issue Brescia University College, 1285 Western Rd, London ON, N6G 3R4, Canada SFRA Review Business phone: 519-432-8353 ext. 28244. Prospect ............................................................................................................................2 [email protected] Assistant Nonfiction Editor SFRA Business Kevin Pinkham The New SFRA Website ..............................................................................................2 College of Arts and Sciences, Ny- “It’s Alive!” ........................................................................................................................3 ack College, 1 South Boulevard, Nyack, NY 10960, phone: 845- Science Fiction and the Medical Humanities ....................................................3 675-4526845-675-4526. [email protected] Feature 101 The New Cosmic Horror: A Genre Molded by Tabletop Roleplaying Fiction Editor Games and Postmodern Horror ..............................................................................7 Jeremy Brett Cushing Memorial Library and Sentience in Science Fiction 101 ......................................................................... 14 Archives, Texas A&M University, Cushing Memorial Library & Archives, 5000 TAMU College Nonfiction Reviews Station, TX 77843. Black and Brown Planets: The Politics of Race in Science Fiction ........ 19 -

Here We Are at 500! the BRL’S 500 to Be Exact and What a Trip It Has Been

el Fans, here we are at 500! The BRL’s 500 to be exact and what a trip it has been. Imagibash 15 was a huge success and the action got so intense that your old pal the Teamster had to get involved. The exclusive coverage of that ppv is in this very issue so I won’t spoil it and give away the ending like how the ship sinks in Titanic. The Johnny B. Cup is down to just four and here are the representatives from each of the IWAR’s promotions; • BRL Final: Sir Gunther Kinderwacht (last year’s winner) • CWL Final: Jane the Vixen Red (BRL, winner of 2017 Unknown Wrestler League) • IWL Final: Nasty Norman Krasner • NWL Final: Ricky Kyle In one semi-final, we will see bitter rivals Kinderwacht and Red face off while in the other the red-hot Ricky Kyle will face the, well, Nasty Normal Krasner. One of these four will win The self-professed “Greatest Tag team wrestler the 4th Johnny B Cup and the results will determine the breakdown of the prizes. ? in the world” debuted in the NWL in 2012 and taunt-filled promos earned him many enemies. The 26th Marano Memorial is also down to the final 5… FIVE? Well since the Suburban Hell His “Teamster Challenge” offered a prize to any Savages: Agent 26 & Punk Rock Mike and Badd Co: Rick Challenger & Rick Riley went to a NWL rookie who could capture a Tag Team title draw, we will have a rematch. The winner will advance to face Sledge and Hammer who won with him, but turned ugly when he kept blaming the CWL bracket. -

Collision Course

FINAL-1 Sat, Jul 7, 2018 6:10:55 PM Your Weekly Guide to TV Entertainment for the week of July 14 - 20, 2018 HARTNETT’S ALL SOFT CLOTH CAR WASH Collision $ 00 OFF 3ANY course CAR WASH! EXPIRES 7/31/18 BUMPER SPECIALISTSHartnett's Car Wash H1artnett x 5` Auto Body, Inc. COLLISION REPAIR SPECIALISTS & APPRAISERS MA R.S. #2313 R. ALAN HARTNETT LIC. #2037 DANA F. HARTNETT LIC. #9482 Ian Anthony Dale stars in 15 WATER STREET “Salvation” DANVERS (Exit 23, Rte. 128) TEL. (978) 774-2474 FAX (978) 750-4663 Open 7 Days Mon.-Fri. 8-7, Sat. 8-6, Sun. 8-4 ** Gift Certificates Available ** Choosing the right OLD FASHIONED SERVICE Attorney is no accident FREE REGISTRY SERVICE Free Consultation PERSONAL INJURYCLAIMS • Automobile Accident Victims • Work Accidents • Slip &Fall • Motorcycle &Pedestrian Accidents John Doyle Forlizzi• Wrongfu Lawl Death Office INSURANCEDoyle Insurance AGENCY • Dog Attacks • Injuries2 x to 3 Children Voted #1 1 x 3 With 35 years experience on the North Insurance Shore we have aproven record of recovery Agency No Fee Unless Successful While Grace (Jennifer Finnigan, “Tyrant”) and Harris (Ian Anthony Dale, “Hawaii Five- The LawOffice of 0”) work to maintain civility in the hangar, Liam (Charlie Row, “Red Band Society”) and STEPHEN M. FORLIZZI Darius (Santiago Cabrera, “Big Little Lies”) continue to fight both RE/SYST and the im- Auto • Homeowners pending galactic threat. Loyalties will be challenged as humanity sits on the brink of Business • Life Insurance 978.739.4898 Earth’s potential extinction. Learn if order can continue to suppress chaos when a new Harthorne Office Park •Suite 106 www.ForlizziLaw.com 978-777-6344 491 Maple Street, Danvers, MA 01923 [email protected] episode of “Salvation” airs Monday, July 16, on CBS. -

Turning Pain Into Power: Traffi Cking Survivors’ Perspectives on Early Intervention Strategies

Turning Pain into Power: Traffi cking Survivors’ Perspectives on Early Intervention Strategies Produced by the The contents of this publication may be adapted and reprinted with the following acknowledgement: “This material was adapted from the Family Violence Prevention Fund publication entitled Turning Pain into Power: Trafficking Survivors’ Perspectives on Early Intervention Strategies.” Family Violence Prevention Fund 383 Rhode Island Street, Suite 304 San Francisco, CA 94103-5133 TEL: 415.252.8900 TTY: 800.595.4889 FAX: 415.252.8991 www.endabuse.org [email protected] ©2005 Family Violence Prevention Fund. All Rights Reserved. Turning Pain into Power: Trafficking Survivors’ Perspectives on Early Intervention Strategies Family Violence Prevention Fund In Partnership with the World Childhood Foundation October 2005 AssessingTurning the PainNeeds into of Power:Trafficked Trafficking Young Women Survivors’ and Perspectives Children:Health ResponseWhat on Earlyis the Intervention RoleTrafficking of Health Strategies Report Care? Acknowledgments The Family Violence Prevention Fund (FVPF) is extremely grateful to all the people who made this project possible. In particular, the FVPF extends deep gratitude to all the survivors of human trafficking who courageously shared their experiences with us. We are honored to learn from their stories and hope that their experiences continue to inform and direct future public policy, intervention strategies, and prevention efforts. Likewise, we thank the advocates and activists who work tirelessly to empower these women and children to regain their lives completely. The Advisory Committee members who gave their input and expertise to this project were invaluable. Their pioneering work in the field of anti-human trafficking and dedication to helping survivors restore their well-being have enriched and informed this research from its inception. -

Beyond the Bodice Ripper: Innovation and Change in The

© 2014 Andrea Cipriano Barra ALL RIGHTS RESERVED BEYOND THE BODICE RIPPER: INNOVATION AND CHANGE IN THE ROMANCE NOVEL INDUSTRY by ANDREA CIPRIANO BARRA A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School—New Brunswick Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Sociology Written under the direction of Karen A. Cerulo And approved by _______________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey OCTOBER 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Beyond the Bodice Ripper: Innovation and Change in the Romance Novel Industry By ANDREA CIPRIANO BARRA Dissertation Director: Karen A. Cerulo Romance novels have changed significantly since they first entered the public consciousness. Instead of seeking to understand the changes that have occurred in the industry, in readership, in authorship, and in the romance novel product itself, both academic and popular perception has remained firmly in the early 1980s when many of the surface criticisms were still valid."Using Wendy Griswold’s (2004) idea of a cultural diamond, I analyze the multiple and sometimes overlapping relationships within broader trends in the romance industry based on content analysis and interviews with romance readers and authors. Three major issues emerge from this study. First, content of romance novels sampled from the past fourteen years is more reflective of contemporary ideas of love, sex, and relationships. Second, romance has been a leader and innovator in the trend of electronic publishing, with major independent presses adding to the proliferation of subgenres and pushing the boundaries of what is considered romance. Finally, readers have a complicated relationship with the act of reading romance and what the books mean in their lives. -

The Matrix As an Introduction to Mathematics

St. John Fisher College Fisher Digital Publications Mathematical and Computing Sciences Faculty/Staff Publications Mathematical and Computing Sciences 2012 What's in a Name? The Matrix as an Introduction to Mathematics Kris H. Green St. John Fisher College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/math_facpub Part of the Mathematics Commons How has open access to Fisher Digital Publications benefited ou?y Publication Information Green, Kris H. (2012). "What's in a Name? The Matrix as an Introduction to Mathematics." Mathematics in Popular Culture: Essays on Appearances in Film, Fiction, Games, Television and Other Media , 44-54. Please note that the Publication Information provides general citation information and may not be appropriate for your discipline. To receive help in creating a citation based on your discipline, please visit http://libguides.sjfc.edu/citations. This document is posted at https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/math_facpub/18 and is brought to you for free and open access by Fisher Digital Publications at St. John Fisher College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. What's in a Name? The Matrix as an Introduction to Mathematics Abstract In my classes on the nature of scientific thought, I have often used the movie The Matrix (1999) to illustrate how evidence shapes the reality we perceive (or think we perceive). As a mathematician and self-confessed science fiction fan, I usually field questionselated r to the movie whenever the subject of linear algebra arises, since this field is the study of matrices and their properties. So it is natural to ask, why does the movie title reference a mathematical object? Of course, there are many possible explanations for this, each of which probably contributed a little to the naming decision. -

Cinema As a Tool for Development

MSc Thesis Cinema as a Tool for Development Investigating the Power of Mobile Cinema in the Latin American Context By Philippine Sellam 1 In partial requirement of: Master of Sustainable Development/ International Development track Faculty of Geosciences, Utrecht University Student: Philippine Sellam (3227774) [email protected] Under the supervision of: Gery Nijenhuis Utrecht, August 2014 Cover Picture and full page pictures between chapters: The public of mobile cinema/Fieldwork 2014 Title font: ‘Homeless font’ purchased from the Arells Foundation (www.homelessfonts.org) 2 Everything you can imagine is real - Picasso 3 Abstract During the last fifteen years, mobile cinema has sparked new interest in the cinema and development sectors. Taking cinema out of conventional theatres and bringing it to the people by transporting screening equipment on trucks, bicycles or trains and setting up ephemeral cinemas in the public space. Widening the diffusion of local films can provide strong incentives to a region or a country’s cinematographic industry and stimulate the production of independent films on socially conscious themes. But the main ambition of most mobile cinema projects is to channel the power of cultural community encounters to trigger critical social reflections and pave the way for social transformation. Just as other cultural activities, gathering to watch a film can bring new inspirations and motivations, which are subjective drivers for actor-based and self-sustained community change. Research is needed to substantiate the hypothesis that mobile cinema contributes to social change in the aforementioned sense. Therefore, the present work proposes to take an investigative look into mobile cinema in order to find out the ways and the extent to which it contributes to actor-based community development. -

The Journal of Shakespeare and Appropriation 11/14/19, 1'39 PM

Borrowers and Lenders: The Journal of Shakespeare and Appropriation 11/14/19, 1'39 PM ISSN 1554-6985 VOLUME XI · (/current) NUMBER 2 SPRING 2018 (/previous) EDITED BY (/about) Christy Desmet and Sujata (/archive) Iyengar CONTENTS On Gottfried Keller's A Village Romeo and Juliet and Shakespeare Adaptation in General (/783959/show) Balz Engler (pdf) (/783959/pdf) "To build or not to build": LEGO® Shakespeare™ Sarah Hatchuel and the Question of Creativity (/783948/show) (pdf) and Nathalie (/783948/pdf) Vienne-Guerrin The New Hamlet and the New Woman: A Shakespearean Mashup in 1902 (/783863/show) (pdf) Jonathan Burton (/783863/pdf) Translation and Influence: Dorothea Tieck's Translations of Shakespeare (/783932/show) (pdf) Christian Smith (/783932/pdf) Hamlet's Road from Damascus: Potent Fathers, Slain Yousef Awad and Ghosts, and Rejuvenated Sons (/783922/show) (pdf) Barkuzar Dubbati (/783922/pdf) http://borrowers.uga.edu/7168/toc Page 1 of 2 Borrowers and Lenders: The Journal of Shakespeare and Appropriation 11/14/19, 1'39 PM Vortigern in and out of the Closet (/783930/show) Jeffrey Kahan (pdf) (/783930/pdf) "Now 'mongst this flock of drunkards": Drunk Shakespeare's Polytemporal Theater (/783933/show) Jennifer Holl (pdf) (/783933/pdf) A PPROPRIATION IN PERFORMANCE Taking the Measure of One's Suppositions, One Step Regina Buccola at a Time (/783924/show) (pdf) (/783924/pdf) S HAKESPEARE APPS Review of Stratford Shakespeare Festival Behind the M. G. Aune Scenes (/783860/show) (pdf) (/783860/pdf) B OOK REVIEW Review of Nutshell, by Ian McEwan -

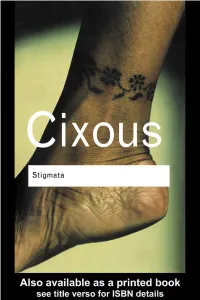

Stigmata: Escaping Texts

Stigmata ‘Hélène Cixous is in my eyes, today, the greatest writer in the French language… Stigmata is henceforth a classic…. One of her most recent masterpieces.’ Jacques Derrida Routledge Classics contains the very best of Routledge publishing over the past century or so, books that have, by popular consent, become established as classics in their field. Drawing on a fantastic heritage of innovative writing published by Routledge and its associated imprints, this series makes available in attractive, affordable form some of the most important works of modern times. For a complete list of titles visit http://www.routledgeclassics.com/ Hélène Cixous Stigmata Escaping texts With a foreword by Jacques Derrida and a new preface by the author London and New York First published 1998 by Routledge First published in Routledge Classics 2005 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxfordshire, OX14 4RN Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge New York, NY 100 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. “To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge's collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk.” © 1998, 2005 Hélène Cixous Index compiled by Indexing Specialists (UK) Ltd, 202 Church Road, Hove, East Sussex BN3 2DJ, UK All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. -

LESSON 5: Boneshaker by Cherie Priest

LESSON 5: Boneshaker by Cherie Priest On the forum, I gave you the following assignment: Read the first 5 pages of Boneshaker by Cherie Priest. List the Steampunk elements you find. Then list the ESSENTIAL Steampunk genre elements, and then the Character descriptions, then setting Your chart will look something like this: STEAMPUNK ...................... ESSENTIAL ...................CHARACTER ...........SETTING ELEMENTS ......................... ELEMENTS.....................ELEMENTS...............ELEMENTS black overcoat black overcoat 11 crooked stairs 11 crooked stairs and so on you can find Boneshaker here at Amazon The table part didn’t come out very well so here’s a better version. I added the word “ALL” to the column labels because I wanted you to understand that in those columns I’m not looking for any specific elements other than those labeled. For instance, under “CHARACTER ELEMENTS (ALL)” give all the character elements you find, not just elements pertaining to the Steampunk genre. STEAMPUNK ESSENTIAL CHARACTER SETTING ELEMENTS (ALL) STEAMPUNK ELEMENTS ELEMENTS (ALL) ELEMENTS (ALL) Black overcoat Black overcoat 11 crooked stairs 11 crooked stairs Goth, Gadgets & Grunge: Steampunk Stories with Style!© By Pat Hauldren LESSON 5: Boneshaker by Cherie Priest / 2 If you’ll notice on the link I provided for Boneshaker at Amazon.com, it’s listed as “ (Sci Fi Essential Books) “ and baby, that’s where *I* want to be! I couldn’t find a specific definition for exactly what that term meant at Amazon.com, but just from the term itself, you can tell it’s the list of books that, while aren’t classics yet, are becoming so for various reasons.