Protected Area Management: Collection and Use of Visitor Data Volume 1: Summary and Recommendations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gondwana Rainforests of Australia State of Conservation Update - April 2020 © Commonwealth of Australia 2020

Gondwana Rainforests of Australia State of Conservation update - April 2020 © Commonwealth of Australia 2020 Ownership of intellectual property rights Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights) in this publication is owned by the Commonwealth of Australia (referred to as the Commonwealth). Creative Commons licence All material in this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence except content supplied by third parties, logos and the Commonwealth Coat of Arms. Inquiries about the licence and any use of this document should be emailed to [email protected]. Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment GPO Box 858 Canberra ACT 2601 Telephone 1800 900 090 Web .gov.au The Australiaenvironmentn Government acting through the Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment has exercised due care and skill in preparing and compiling the information and data in this publication. Notwithstanding, the Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment, its employees and advisers disclaim all liability, including liability for negligence and for any loss, damage, injury, expense or cost incurred by any person as a result of accessing, using or relying on any of the information or data in this publication to the maximum extent permitted by law. Contents Introduction ....................................................................................................................................... 4 Outstanding Universal Value ............................................................................................................ -

Dorrigo National Park Ecosystems at Risk Activity Outline

Ecosystems at Risk Dorrigo National Park North Coast Region Location description and highlights Dorrigo National Park is located astride the Great Escarpment at the edge of Activity outline the Dorrigo Plateau and above the heart of the Bellinger Valley. Its magnificent rainforests are part of the Gondwana Rainforests of Australia World Heritage area, are of international significance, and are easily accessed via boardwalks and sealed walking tracks. Views from the Skywalk boardwalk emphasize aspects of both geographical location, climate, geology, and human impacts on the site. About this program Levels: The field trip is designed to complement a case study of a particular ecosystem at Stage 6 risk, providing an opportunity to observe a highly diverse rainforest ecosystem, its geographical location and extent, altitude, continuity and the effects on it of Key learning areas: biophysical interactions, human impacts and contemporary management practices. GEOGRAPHY - Ecosystems at risk It also provides an opportunity to question a representative of the management Key outcomes: authority about the global significance of the site, possible future impacts, and . Students explain the factors which strategies for managing these. An additional 3hr exercise may be added, where place ecosystems at risk and the students role-play characters who play a variety of roles in the evaluation and reasons for their protection management of risk factors. In addition, detailed information about these aspects . Students evaluate environmental management strategies in terms of of the site are provided in a resource package available on the Department website. ecological sustainability . Students plan geographical enquiries to analyse and synthesise information Objectives from a variety of sources Students gain an understanding of the vulnerability of ecosystems to natural stress and human impacts. -

Engaging with the Chinese Non-Group Leisure Market

GREAT DRIVES IN NSW Enjoy the sheer pleasure of the journey with inspirational drives in NSW. Visitors will discover views, wildlife, national parks full of natural wonders, beaches that make the rest of the world envious and quiet country towns with plenty of stories to tell. Essential lifestyle ingredients such as wineries, great regional dining and fantastic places to spend the night cap it all off. Travel slowly and discover a state that is full of adventures. The Legendary Pacific Coast Fast facts A scenic coastal drive north from Sydney to Brisbane in Queensland Alternatively, fly to Newcastle, Ballina Byron or the Gold Coast and hire a car 940km from start to finish Why drive it To the west is the Great Dividing Range, green pastures, rainforests, sleepy villages and waterfalls. Along the coast is an almost continuous line of beaches and rocky headlands. The Legendary Pacific Coast has many possible themed itineraries: Culture and Heritage Trail Food and Wine / Farm Gate Journey National Parks Trail Surfing Safari Backpacker / Working Holiday What can visitors do along the way? On the Central Coast, drop into a wildlife or reptile park to meet Australia’s native animals. Stop off at the Hunter Valley for cellar door wine tastings and delicious cheeses. Take a detour along Bucketts Way through deep forest to the historic villages of Stroud and Gloucester. Stop at South West Rocks and visit Smoky Cape Lighthouse for ocean views and to see the historic Trial Bay Gaol. Turn west to Bellingen, explore this New Age village and go on to Dorrigo National Park for World Heritage-listed rainforests and waterfalls. -

Gondwana Rainforests of Australia World Heritage Area

Gondwana Rainforests of Australia World Heritage Area NIO MU MO N RI D T IA A L P W L O A I R D L D N O H E M R I E T IN AG O E PATRIM GONDWANA RAINFORESTS OF AUSTRALIA New England National Park Park National England New Ruming Shane © OUR NATURAL TREASURES WHY WORLD HERITAGE? HOT SPOTS OF BIODIVERSITY Explore the amazing Gondwana A RECORD OF THE PAST Some of the most important and Rainforests of Australia World significant habitats for threatened Heritage Area (Gondwana Rainforests The Gondwana Rainforests WHA species of outstanding universal WHA) within north-east NSW reveals major stages of Earth’s value from the point of view of and south-east Queensland. It’s history. Sheltering in the high science and conservation are a true pilgrimage to see these rainfall and rich soils of the Great contained within the Gondwana magnificent rainforests – places of Escarpment lie remnants of the Rainforests WHA. towering ancient trees, plunging once vast rainforests that covered Of the thousands of different native waterfalls, craggy gorges and the southern supercontinent plant species in Australia, half splendid rainbows. of Gondwana. occur in rainforests. More than 200 These rich and beautiful forests form Few places on Earth contain so many of the plant species found in the some of the most extensive areas of plants and animals that are so closely Gondwana Rainforests WHA are rare diverse rainforest found anywhere related to their ancestors in the or threatened with extinction. in the world and their importance fossil record. is recognised with World Heritage Spectacular remnant landforms listing. -

Identifying the Recreational Value of Reserves

Identifying the Recreational Value of Reserves NEFA BACKGROUND PAPER Identifying the Recreational Value of Reserves Prepared by: Dailan Pugh, 2014 National parks and reserves provide a range of economic values to society including those associated with recreation and conservation. Visitation to, and management of protected areas, also provides stimulation to regional economies from the associated expenditures that occur within the region. Tourism is the most rapidly expanding sector of the regional economy. The long-term economic value of national parks for recreation will often outweigh any short-term economic return from logging, mining and/or grazing. Public land is a highly valued resource, providing the only natural areas for recreation for many residents. The Centre for Coastal Management (1993) note “as indicated by the recreationalist survey … the most significant source of recreational forest visitation comes from the residents of the local government area”. Roy Morgan Research Ltd (2011) undertook a series of telephone surveys to identify visitation to NSW national parks and reserves, estimating 38,057,162 visitors in 2008 and 34,607,247 visitors in 2010 (with the drop considered to be due to extreme weather and overseas travel). Around 12% of people had visited a park in the last 4 weeks. Primary activities in 2010 were walking (50%), water-based activities (18%), picnicking and dining (16%) and touring and sightseeing (10%). Buultjens et. al. (1998) considered that: The natural environment is perceived to be the one of the most important tourist attractions for Australia, and in particular of the north east NSW region. Forested areas represent a significant proportion of tourism and recreational attractions in natural environments (Commonwealth Department of Tourism, 1994; Northern Rivers Regional Development Board, 1994). -

Forestry Revocation and National Parks Reservation Act 1984

Forestry Revocation and National Parks Reservation Act 1984 As at 1 July 2018 Long Title An Act to revoke certain dedications of parts of State forests and part of a timber reserve and to reserve or dedicate the lands the subject of those revocations, and certain other Crown lands, as parts of national parks, a nature reserve and part of a nature reserve. 1 Name of Act This Act may be cited as the Forestry Revocation and National Parks Reservation Act 1984. 2 Revocation of parts of certain State forests The dedications as parts of State forests of the lands described in Schedule 1 are revoked. 3 Revocation of part of a timber reserve The reservation as part of a timber reserve of the land described in Schedule 2 is revoked. 4 Reservation of lands as parts of national parks (1) The lands described in Part 1 of Schedule 1 are reserved as part of the Washpool National Park. (2) The lands described in Part 2 of Schedule 1 are reserved as part of the Dorrigo National Park. (3) The lands described in Part 3 of Schedule 1 and in Schedule 2 are reserved as parts of the Werrikimbe National Park. (4) The lands described in Part 4 of Schedule 1 and in Schedule 3 are reserved as parts of the Barrington Tops National Park. 5 Dedication of lands as a nature reserve or as part of a nature reserve (1) The lands described in Part 5 of Schedule 1 are dedicated as a nature reserve to be known as "Mount Hyland Nature Reserve". -

State of Conservation Update - April 2020

Gondwana Rainforests of Australia State of Conservation update - April 2020 State of Conservation – Gondwana Rainforests of Australia – April 2020 Contents Introduction ....................................................................................................................................... 3 Outstanding Universal Value ............................................................................................................. 3 Impact of the 2019-2020 fires ........................................................................................................... 4 Extent of the fires .......................................................................................................................... 4 Assessment of ecological impacts of the fires ............................................................................. 13 Variability of fire impact .......................................................................................................... 13 Identifying key species affected .............................................................................................. 19 Threatened ecological communities ....................................................................................... 21 Intersection with other conservation issues ............................................................................... 21 Future of Gondwana Rainforests under climate change ......................................................... 21 Weeds and feral animals ........................................................................................................ -

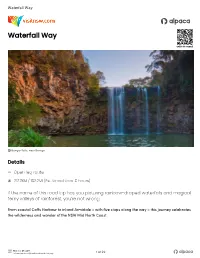

Waterfall Way

Waterfall Way Waterfall Way OPEN IN MOBILE Dangar Falls, near Dorrigo Details Open leg route 212.7KM / 132.2MI (Est. travel time 3 hours) If the name of this road trip has you picturing rainbow-draped waterfalls and magical ferny valleys of rainforest, you’re not wrong. From coastal CoÂs Harbour to inland Armidale – with Êve stops along the way – this journey celebrates the wilderness and wonder of the NSW Mid North Coast. What is a QR code? To learn how to use QR codes refer to the last page 1 of 22 Waterfall Way What is a QR code? To learn how to use QR codes refer to the last page 2 of 22 Waterfall Way 1 Coffs Harbour OPEN IN MOBILE The CoÂs Coast is your starting point for this epic day trip and you'll want to begin with a few adventures. In the town of CoÂs Harbour, the Big Banana Fun Park welcomes you with a 13m banana sculpture (the original Big Thing); inside are attractions ranging from waterslides to a 4D simulator and mini-golf. Save some energy to hike around Muttonbird Island Nature Reserve A kangaroo at Emerald Beach, Coffs Harbour (Giidany Miirlarl), a place of Aboriginal signiÊcance and an important nesting ground for migratory shearwaters. The other migratory species you’ll see here are humpback whales, breaching and blowing between the Solitary Islands from June through October. For a loftier look, take the plunge with CoÂs Skydivers, oÂering breathtaking – literally – views over the coast’s long stretches of sand. Driving out of town, pause at Sapphire Beach to learn about the local Gumbaynggirr people on a Wajaana Yaam Adventure Tour, exploring the marine park and oÂering a taste of bush tucker. -

FERAL PIG MANAGEMENT in the Australian Alps National Parks

FERAL PIG MANAGEMENT in the Australian Alps National Parks Workshop Khancoban, NSW 25-27 April 2005 1 © Australian Alps Liaison Committee, February 2006. This work is copyright. The Australian Alps Liaison Committee holds copyright in this printed and CD edition. Apar t from any use as permitted under t he Copyright Act 1968, no part may be r eproduced by any proc ess without written permission. Copyright in individual papers, PowerPoint presentations, photographs and graphic images are held by the author/owner. Permission for reproduction of these items should also be directed to the author/copyright owner. The opinions expressed in this docum ent are those of the authors and do not necessarily express t he views of any of the government ministers, heads of authorities or the Australian Alps Liaison Committee. Report compiled by Trish Macdonald for the Australian Alps Cooperative Management Program 2 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION 5 WORKSHOP OBJECTIVES 5 WORKSHOP SESSIONS 6 PAPERS Principles for effective feral pig control 11 Jim Hone An Overview of Current Techniques for Feral Pig Control. 21 John A Meany Animal Welfare And Best Practice Pest Animal Control: Development Of Codes Of Practice and Standard Operating Procedures Glen Saunders and Trudy Sharp 24 Involvement of the National Feral Animal Control Program (NFACP) in feral pig management Quentin Hart 28 Feral Pig Research at the Pest Animal Control CRC Steve Lapidge 34 Feral Pig Control in Namadgi National Park – ACT Bill Woodruff 40 Feral Pig Management in Victoria Peter Kambouris & Charlie Pascoe 43 A Feral Pig Control Program in Kosciusko National Park, NSW Craig Smith 50 A Co-operative Feral Pig Control Program in the South East Forests of NSW Dayna Blackmore 51 Oberon Pest Management Group John Meany 53 APPENDICES Workshop Agenda Workshop Participants 3 Available on CD - Powerpoint Presentations Contact the Program Manager [email protected] • Principles for effective feral pig control. -

Ame a NEW SOUTH WALES RAINFORESTS

~o ~OMINATION TO THE WORLD HERITAGE LIST Conventlon concernlng tne Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage ~ame a NEW SOUTH WALES RAINFORESTS Identirica~ion NOa 368 Date received by WH Secretariat I 20.11.85 Contracting State Party having submitted the nomination of the property in accoraance wlth the Convention a AUSTRALIA Summary prepared by IUCN (Aprll 1986) based on the original ~omination submitted by Australia. This original and all documents presented in support of this nomination will be available for consultation at the meetings of the Bureau and the Committee. 1. LOCA'.J.'ION a The norunation proposal consists of seven separate clusters containing a total of 17 different national parks, flora reserves and nature reserves. The sites extend from the NSW!Queensland border In the north, 750 km south along the south-east coastal region of Australia. 36°20'S-28°15'S, 150 0 05'E-153°20'E. 2. JURIuICAL DATA, All tt,e nominatlon areas are in public ownership. Fourteen of the sites (national parks and nature reserves) are administered by the NSW National Parks and Wildlife serVlce and three (flora reserves) are administered by the Forestry Commission of NSW. Dates of establishment and boundary modifications date from 1~31 to the present wlth the major acquisitions made between 1964 and 1983. The Acts which apply are the National Parks and Wildlife Act (1974), the Forestry Act (1916), and the Forestry Revocation and National Park Reservation Act (1983, 1984). 3. IDENTIFICATION a The 17 ralnforest reserves are groupea in seven clusters from north to south along the Great Dividing Range as followsl a) Tweea Volcano Group includesa e) Hastings Group includes, Border Ranges National Park 31,229ha Werrikimbe National Park 34,753ha Limpinwooa Nature Reserve 2,443ha Mt. -

1 Grand Pacific Drive 200Km 2 Kosciuszko Alpine Way 170Km 3 Rainforest Way 270Km 4 Darling River Run 940Km 5 Mighty Murray River

1 GRAND PACIFIC DRIVE 200KM Sydney to Jervis Bay via Royal National Park, Wollongong, Shellharbour, Kiama and Shoalhaven. 2 KOSCIUSZKO ALPINE WAY 170KM Cooma to Khancoban via Jindabyne and Kosciuszko National Park. 3 RAINFOREST WAY 270KM Byron Bay to Tabulam via Murwillumbah, Uki, Mebbin National Park, Nightcap National Park, Lismore and Casino. 4 DARLING RIVER RUN 940KM Walgett to Wentworth via Brewarrina, Bourke, Louth, Tilpa, Wilcannia, Menindee and Pooncarie. 5 MIGHTY MURRAY RIVER DRIVE 830KM Albury to Wentworth via Howlong, Corowa, Yarrawonga Mulwala, Tocumwal, Echuca Moama, Barham, Balranald, Mungo National Park. 6 GREATER BLUE MOUNTAINS DRIVE 220KM Sydney to the Hawkesbury via Katoomba, Lithgow, Mount Tomah and Bilpin. 7 CENTRAL TO OUTBACK NSW 780KM Dubbo to Broken Hill via Nyngan, Cobar and Wilcannia. 8 WATERFALL WAY 210KM Coffs Harbour to Armidale via Bellingen, Dorrigo National Park, Dorrigo, Ebor and Wollomombi. 9 RIVERINA TO SNOWY VALLEYS WAY 400KM Griffith to Tumbarumba via Leeton, Narrandera, Coolamon, Junee, Wagga Wagga and Tumut. 10 COAST AND COUNTRY HIGHLIFE 610KM Sydney to Robertson via Bowral, Goulburn, Bungendore, Braidwood, Batemans Bay, Milton, Mollymook, Huskisson, Jervis Bay, Gerringong and Kiama. 11 HIGH COUNTRY TO CRUISING COAST 480KM Cooma to Bungendore via Bega, Merimbula, Cobargo, Tilba Tilba, Narooma, Moruya, Mogo, Batemans Bay and Braidwood. 12 FOOD LOVER’S LOOP 540KM Sydney to the Hunter Valley via the Hawkesbury, Mount Tomah, Lithgow, Mudgee, Rylstone and the Upper Hunter. 13 LEGENDARY PACIFIC COAST 820KM Lake Macquarie to Tweed Heads via Newcastle, Port Stephens, Port Macquarie, South West Rocks, Coffs Harbour and Byron Bay. 14 SYDNEY TO MELBOURNE COASTAL DRIVE 410KM Wollongong to Merimbula via Jamberoo, Kiama, Jervis Bay, Ulladulla, Batemans Bay, Moruya, Tuross Head, Bodalla, Narooma and Tilba. -

Dorrigo National Park Plan of Management

DORRIGO NATIONAL PARK PLAN OF MANAGEMENT NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service October 1998 This plan of management was adopted by the Minister for the Environment on 4 October 1998. Acknowledgements: This plan of management has been prepared by staff of the Dorrigo District Office of the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service Crown Copyright 1998. Use permitted with appropriate acknowledgement. ISBN 0 7310 7688 5 FOREWORD Dorrigo National Park has an area of 7 885 hectares and is located 4 kilometres east of Dorrigo township which in turn lies 590 kilometres by road from Sydney. Dorrigo township is the centre of the rich agricultural lands of the Dorrigo Plateau. The town of Bellingen lies 25 kilometres to the east of the park and is the main town servicing the Bellinger Valley. The mid-north coast is within one hours drive of the park with the increasing population of centres such as Coffs Harbour and Nambucca Heads an important factor in park use and management. Part of Dorrigo Mountain was first protected in 1901. The area of reserved lands was progressively enlarged and granted increased protection until in 1967 when it was reserved under the National Parks and Wildlife Act, 1967 as a State Park. Under the National Parks and Wildlife Act of 1974 Dorrigo State Park was accorded national park status. In 1986 it was incorporated in the World Heritage List as one of the Sub-tropical and Warm Temperate Rainforest Parks of Eastern Australia, now known as the Central Eastern Rainforest Reserves of Australia. Dorrigo National Park is one of an important group of conservation areas on the Great Escarpment which include New England, Guy Fawkes River, Cathedral Rocks and Oxley Wild Rivers National Parks and Mount Hyland and Guy Fawkes River Nature Reserves.