Download Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Told to Take a Hike

Your news and views? Email us at [email protected] September 2, 2011 the Grey Nomad Times In this issue: •Satphone prices plunge •Meet our GN character •A laughing matter Grey nomad Park ‘developers’ gold diggers eye pay dirt told to take a hike There’s gold in them thar The Victorian government hills and the soaring value of looks set to reject persistent the precious metal has sent and growing calls to allow grey nomads hunting for it more private development in like never before. the state’s magnificent national Many find the on-the-road parks … at least for now. lifestyle perfectly suited to Proposals put forward by gem fossicking and gold business groups included boat prospecting … and metal cruises at Wilsons Promontory, detectors don’t take up much new hotel accommodation at space in the van. Point Nepean, and privately Like many former gold operated tourist walking huts rush towns, Mudgee, on the Great Ocean Walk about 250kms northwest from Apollo Bay to the Twelve of Sydney, has noticed the Apostles. influx. Prospecting supply The proposals have been the shops have seen many more Privately-owned walking huts too big a step? Pic: Tourism Vic subject of a review by the new arrivals in the past six Victorian Competition and Victoria that private develop- for such as hiking, camping, months. And it is the life- Efficiency Commission. ments should not take place cross-country skiing and fam- style as well as the potential However, Environment Min- inside national parks,” it ily day trips,” they said. “Tak- windfall that sends people ister Ryan Smith, says his goal said. -

Monograph of the Family Atherospermataceae R.Br

ar. UOT{OGR.APH OF gTB MR.Br. by RIGIIARD SCHODDE, B.Sc.(Uæs, ) vol¡¡oe II INDICES and. ILLT¡SIRÁTIoI{S - SIIBMIT]ED FOR SIIE DEGEffi OF DOCTOR OT'PHII¡SOHtr îO 1TIE IJNilTER.9IIY OF ADEÏATDE BdMT{T DXPARTMÐÍI tÁARCrr 1969 a SASTE OF COI\ITM{TS Vo}¡ne IÏ I. INDEX TO H¡RB¡.RIUM COT'T'ECTIOI\ìS 5W II. INDEX TO WOOD COI'T,ECTIONS 5Bo III. INDEX r0 PoLûEN c0Tf,r:cTI0I{S 583 fr/. INEEX TO IJMRAfi]RE REflERENctsS 585 vo T}IDEX TO SCIENTTFIC T{¿MES 6w v:f. ITIIJSTA.NTIONS Figures 1-58 Maps 1-10 5+7 I INDEX TO HERBARIUM COT,T,T:CTTONS (Collections v¡ithout j¡rd-ication of provenance or from cu1- tivation aro not includ.ed.. Ror.¡nd. brackets i¡rd.icate tho d.ate of coflection v¡here a colloctorts mmber is not given' and- braokets on the co]l-ectÌon label. Square brackets j¡d.icate d-ata not present or occurrirrg ilconsistently on herbarium collections, ) Àthero sDerma moschattun l"abi]l" subs'p. j:rtegrj-foliÌ¡ì1 (À.Cr:nn.ex Tu1' )Scnoaae Botche (x.18!l): NS\T: fentworth Faflsr Boornan (iii.f9f5): NST: Blact<heath. :: Boornan (xii.1915):- NSr-rl: Barrington Tops" constabl_e (f7.i.r95O): I{SvT: Blackheath. constable 27.i.:1¡90+): lüS$: tr'erLoral Falls, Lavrson. -A. C'nni¡reha¡n iI82+" þv,t826): K[x 2], SING: Bluo Mou¡rtains. Deane (ii.faae ): IÆì1,: Katoomba. Duff JlE: [El': Iøchlan d'istrict' Iary (ZO.iv.I95l): NSI{: Gunini, Upper Maru:ing river' - O'D'E' l.- Evans,l I92O: C.ANB: Mi¡nehaha Falls, Katomba. -

Newsletter for Landcare and Dunecare in Byron Shire

Newsletter for Landcare and Dunecare in Byron Shire http://www.brunswickvalleylandcare.org.au/ September 2019 Completion of National Landcare Grant in Yalla Kool Reserve by Alison Ratcliffe The project which has allowed Brunswick Valley Landcare and the volunteers of Yalla Kool Landcare group to upgraded the walking track through Yalla Kool Reserve in Ocean Shores is now complete. The project has been a great success with 3 community days with 92 attendees, 0.5 ha of regeneration and planting of 420 plants as well as the significant improvement to the walking track. Yalla Kool Reserve was successful in receiving $49,816 through the Australian Governments National Landcare Program Environments Small Grants to improve the condition and function of this suburban reserve in Ocean Shores. Alison Ratcliffe, Landcare Support Officer said “The project has allowed the walking track to be upgraded and formalised. The walking track that winds through the reserve is now accessible in all weathers. It provides a great link between the Ocean Shores shopping centre and Devine’s Hill lookout through a beautiful natural environment”. These photos show the difference from the start of the project in September 2018 to this week. This project has been supported by funding from the Australian Governments National Landcare Program. 1 For the full program https://www.bigscrubrainforest.org/big-scrub-rainforest-day/ 2 Locally Brunswick Valley Landcare are holding guided Rainforest Identification walks through Heritage Park – Maslam Arboretum in Mullumbimby. To book on any or all of the 3 walks please visithttps://www.eventbrite.com.au/e/big-scrub- rainforest-day-guided-walks-and-talks-tickets- 68921531155 Weed Identification Walk Thursday 26th September at 10am-12noon David Filipczyk, Byron Shire Council Bush Regenerator, will lead a weed walk along the Byron Shire Council managed site on Casuarina St starting from St John's Primary School carpark. -

Approved Conservation Advice for Rutidosis Heterogama (Heath Wrinklewren)

This Conservation Advice was approved by the Minister/Delegate of the Minister on: 3/07/2008. Approved Conservation Advice (s266B of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999). Approved Conservation Advice for Rutidosis heterogama (Heath Wrinklewren) This Conservation Advice has been developed based on the best available information at the time this conservation advice was approved. Description Rutidosis heterogama, Family Asteraceae, also known as the Heath Wrinklewren or Heath Wrinklewort, is a perennial herb with decumbent (reclining to lying down) to erect stems, growing to 30 cm high (Harden, 1992; DECC, 2005a). The tiny yellow flowerheads are probably borne March to April (Leigh et al., 1984), chiefly in Autumn (Harden, 1992) or November to January. Seeds are dispersed by wind (Clarke et al., 1998) and the species appears to require soil disturbance for successful recruitment (Clarke et al., 1998). Conservation Status Heath Wrinklewren is listed as vulnerable. This species is eligible for listing as vulnerable under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cwlth) (EPBC Act) as, prior to the commencement of the EPBC Act, it was listed as vulnerable under Schedule 1 of the Endangered Species Protection Act 1992 (Cwlth). The species is also listed as vulnerable on the Threatened Species Conservation Act 1995 (NSW). Distribution and Habitat Heath Wrinklewren is confined to the North Coast and Northern Tablelands regions of NSW. It is known from the Hunter Valley to Maclean, Wooli to Evans Head, and Torrington (Harden, 1992). It occurs within the Border Rivers–Gwydir, Hunter–Central Rivers and Northern Rivers (NSW) Natural Resource Management Regions. -

Lamington National Park Management Plan 2011

South East Queensland Bioregion Prepared by: Planning Services Unit Department of Environment and Resource Management © State of Queensland (Department of Environment and Resource Management) 2011 Copyright protects this publication. Except for purposes permitted by the Copyright Act 1968, reproduction by whatever means is prohibited without the prior written permission of the Department of Environment and Resource Management. Enquiries should be addressed to Department of Environment and Resource Management, GPO Box 2454, Brisbane Qld 4001. Disclaimer This document has been prepared with all due diligence and care, based on the best available information at the time of publication. The department holds no responsibility for any errors or omissions within this document. Any decisions made by other parties based on this document are solely the responsibility of those parties. Information contained in this document is from a number of sources and, as such, does not necessarily represent government or departmental policy. This management plan has been prepared in accordance with the Nature Conservation Act 1992. This management plan does not intend to affect, diminish or extinguish native title or associated rights. Note that implementing some management strategies might need to be phased in according to resource availability. For information on protected area management plans, visit <www.derm.qld.gov.au>. If you need to access this document in a language other than English, please call the Translating and Interpreting Service (TIS National) on 131 450 and ask them to telephone Library Services on +61 7 3224 8412. This publication can be made available in alternative formats (including large print and audiotape) on request for people with a vision impairment. -

Australia-15-Index.Pdf

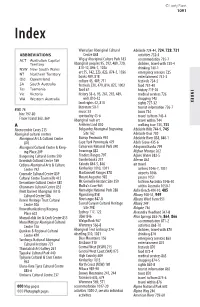

© Lonely Planet 1091 Index Warradjan Aboriginal Cultural Adelaide 724-44, 724, 728, 731 ABBREVIATIONS Centre 848 activities 732-3 ACT Australian Capital Wigay Aboriginal Culture Park 183 accommodation 735-7 Territory Aboriginal peoples 95, 292, 489, 720, children, travel with 733-4 NSW New South Wales 810-12, 896-7, 1026 drinking 740-1 NT Northern Territory art 55, 142, 223, 823, 874-5, 1036 emergency services 725 books 489, 818 entertainment 741-3 Qld Queensland culture 45, 489, 711 festivals 734-5 SA South Australia festivals 220, 479, 814, 827, 1002 food 737-40 Tas Tasmania food 67 history 719-20 INDEX Vic Victoria history 33-6, 95, 267, 292, 489, medical services 726 WA Western Australia 660, 810-12 shopping 743 land rights 42, 810 sights 727-32 literature 50-1 tourist information 726-7 4WD 74 music 53 tours 734 hire 797-80 spirituality 45-6 travel to/from 743-4 Fraser Island 363, 369 Aboriginal rock art travel within 744 A Arnhem Land 850 walking tour 733, 733 Abercrombie Caves 215 Bulgandry Aboriginal Engraving Adelaide Hills 744-9, 745 Aboriginal cultural centres Site 162 Adelaide Oval 730 Aboriginal Art & Cultural Centre Burrup Peninsula 992 Adelaide River 838, 840-1 870 Cape York Penninsula 479 Adels Grove 435-6 Aboriginal Cultural Centre & Keep- Carnarvon National Park 390 Adnyamathanha 799 ing Place 209 Ewaninga 882 Afghan Mosque 262 Bangerang Cultural Centre 599 Flinders Ranges 797 Agnes Water 383-5 Brambuk Cultural Centre 569 Gunderbooka 257 Aileron 862 Ceduna Aboriginal Arts & Culture Kakadu 844-5, 846 air travel Centre -

New England Regional

A B TO INGLEWOOD 18km C D E TO WARWICK 45km Source: © Land and Property Mt (locality) (locality) Management Authority Bullaganang Bullecourt Fleurbaix PANORAMA AVENUE BATHURST 2795 (locality) 151º00'E 151º30'E 152º00'E www.lpma.nsw.gov.au Glenarbon 89 (locality) Cottonvale (locality) Messines MARYLAND Magee Thulimbah NAT PK 1 QUEENSLAND (locality) The Summit Creek Cannon Browns Mt Creek (locality) Mtn You You Beebo Black Ck (locality) Mtn Pikedale Ten Mallow TOPOFTHETOWN Applethorpe (locality) Creek TOURIST PARK Limevale WAY (locality) 41km BRUXNER Liston Pine Mtn elec TO WOODENBONG 84km WOODENBONG TO A STANTHORPE 1 TO GOONDIWINDI TO NEW SOUTH Fish Hole Bark Mtn Amosfield 24 WALES (locality) 150º30'E Smithfield Oaky 17 DTHINNA (locality) Nundubbermere DTHINNAWAN (locality) NAT PK Mt North Star Mt Pike Jibbinbar Malakoff (locality) Glen Aplin Gunyan TD 7 WAY 1 Texas Coxs Mtn Fletcher Sugarloaf HWY 89 Yetman Texas Mt Eukey Ballandean (locality) 12 44 Silver Spur Glenlyon Black Jack Blue 64 (locality) Glenroy (locality) Mtn 8 Fees apply Nobby (locality) YETMAN BEBO 29º00'S ST F ST F SUNDOWN (locality)Lyra Wolonga SHEARERS (locality) NATIONAL PARK Camp 24 Raleigh Razorback Wyberba Mt (locality) (locality) (locality) Norman 5 Severn 15NATIONAL Bald Tikitere Mountain Bald Rock Mitchell Christie 11 GIRRAWEEN Round Mtn (locality) Lake Glenlyon (locality) RD Hill BURRAL Target NAT PK (locality) Russell YURRUL Atholwood 95 NAT RES Boonoo Hill Ck Boonoo Wallangarra BALD ROCK Ottleys (locality) NAT PK elec Yallaroi Rocky Dam BURRAL (locality) Mole -

Government Gazette of the STATE of NEW SOUTH WALES Number 112 Monday, 3 September 2007 Published Under Authority by Government Advertising

6835 Government Gazette OF THE STATE OF NEW SOUTH WALES Number 112 Monday, 3 September 2007 Published under authority by Government Advertising SPECIAL SUPPLEMENT EXOTIC DISEASES OF ANIMALS ACT 1991 ORDER - Section 15 Declaration of Restricted Areas – Hunter Valley and Tamworth I, IAN JAMES ROTH, Deputy Chief Veterinary Offi cer, with the powers the Minister has delegated to me under section 67 of the Exotic Diseases of Animals Act 1991 (“the Act”) and pursuant to section 15 of the Act: 1. revoke each of the orders declared under section 15 of the Act that are listed in Schedule 1 below (“the Orders”); 2. declare the area specifi ed in Schedule 2 to be a restricted area; and 3. declare that the classes of animals, animal products, fodder, fi ttings or vehicles to which this order applies are those described in Schedule 3. SCHEDULE 1 Title of Order Date of Order Declaration of Restricted Area – Moonbi 27 August 2007 Declaration of Restricted Area – Woonooka Road Moonbi 29 August 2007 Declaration of Restricted Area – Anambah 29 August 2007 Declaration of Restricted Area – Muswellbrook 29 August 2007 Declaration of Restricted Area – Aberdeen 29 August 2007 Declaration of Restricted Area – East Maitland 29 August 2007 Declaration of Restricted Area – Timbumburi 29 August 2007 Declaration of Restricted Area – McCullys Gap 30 August 2007 Declaration of Restricted Area – Bunnan 31 August 2007 Declaration of Restricted Area - Gloucester 31 August 2007 Declaration of Restricted Area – Eagleton 29 August 2007 SCHEDULE 2 The area shown in the map below and within the local government areas administered by the following councils: Cessnock City Council Dungog Shire Council Gloucester Shire Council Great Lakes Council Liverpool Plains Shire Council 6836 SPECIAL SUPPLEMENT 3 September 2007 Maitland City Council Muswellbrook Shire Council Newcastle City Council Port Stephens Council Singleton Shire Council Tamworth City Council Upper Hunter Shire Council NEW SOUTH WALES GOVERNMENT GAZETTE No. -

Birdlife Northern NSW Autumn Campout 2021 DORRIGO Friday 12Th to Sunday 14Th September at Dorrigo Mountain Holiday Park, 3991 Waterfall Way, Ph (02) 6657 2564; Email

BirdLife Northern NSW Autumn Campout 2021 DORRIGO Friday 12th to Sunday 14th September at Dorrigo Mountain Holiday Park, 3991 Waterfall Way, ph (02) 6657 2564; email PROGRAM and OUTINGS (subject to changes/cancellation to comply with NSW COVID public health orders at the time) Friday 12th registration (required for our legal obligations); (TBC) optional guided Night Walk in Dorrigo NP; the evening meal is your own arrangement 3.00 - 5.00pm register in the Meeting Hall at Dorrigo Mountain Holiday Park, near the Park Office (please observe COVID public health orders) - confirm contact details, check outing details, enter 'Final Bird Count', buy raffle tickets, Night Walk payments - $20 (cash only please) TBC: 6.30 - 8.30pm ranger-guided Night Walk (limit 20 people) in Dorrigo National Park, enter your interest on the registration form; payment $20 cash on Friday 12 March. - free choice for Fri & Sat night meals e.g. self-catering in cabins, or use communal kitchen & BBQ facilities at the campground. In Dorrigo town centre: the usual take- away, pub dinner at Dorrigo Heritage Hotel, Chinese at RSL Club (6-8pm), North Dorrigo Restaurant (Fri nights only by booking ph:(02 6657 5150); Bellingen has many eateries (30min drive down Waterfall Way). For Friday or Monday we recommend Canopy Cafe in the pleasant setting of Dorrigo National Park (open 9-4.30). Saturday 5th guided daytime Outings see page 2 (COVID public health orders must be observed) NB: there is no group dinner for this campout, see Friday dining suggestions Sunday 6th guided daytime Outings and 5.00pm for final Bird Call byo drinks & snacks in the Meeting Hall, Dorrigo Mountain Holiday Park (COVID number limit may apply) Saturday 5th and Sunday 6th Outings Program page 2 NOTE your departure time & meeting location - please be on time, your group may not be able to wait Because environmental conditions or leaders may change, or new information is received, routes could be modified by guides on the day for safety reasons and to maximise bird-watching opportunities along each route. -

EPBC Protected Matters Database Search Results

FLORA AND FAUNA TECHNICAL REPORT Gold Coast Quarry EIS ATTACHMENT A – EPBC Protected Matters Database Search Results April 2013 Cardno Chenoweth 71 EPBC Act Protected Matters Report This report provides general guidance on matters of national environmental significance and other matters protected by the EPBC Act in the area you have selected. Information on the coverage of this report and qualifications on data supporting this report are contained in the caveat at the end of the report. Information about the EPBC Act including significance guidelines, forms and application process details can be found at http://www.environment.gov.au/epbc/assessmentsapprovals/index.html Report created: 01/06/12 14:33:07 Summary Details Matters of NES Other Matters Protected by the EPBC Act Extra Information Caveat Acknowledgements This map may contain data which are ©Commonwealth of Australia (Geoscience Australia), ©PSMA 2010 Coordinates Buffer: 6.0Km Summary Matters of National Environment Significance This part of the report summarises the matters of national environmental significance that may occur in, or may relate to, the area you nominated. Further information is available in the detail part of the report, which can be accessed by scrolling or following the links below. If you are proposing to undertake an activity that may have a significant impact on one or more matters of national environmental significance then you should consider the Administrative Guidelines on Significance - see http://www.environment.gov.au/epbc/assessmentsapprovals/guidelines/index.html World Heritage Properties: None National Heritage Places: None Wetlands of International 1 Great Barrier Reef Marine Park: None Commonwealth Marine Areas: None Threatened Ecological Communities: 1 Threatened Species: 57 Migratory Species: 27 Other Matters Protected by the EPBC Act This part of the report summarises other matters protected under the Act that may relate to the area you nominated. -

Emergency Response to Australia's Black Summer 2019–2020

animals Commentary Emergency Response to Australia’s Black Summer 2019–2020: The Role of a Zoo-Based Conservation Organisation in Wildlife Triage, Rescue, and Resilience for the Future Marissa L. Parrott 1,*, Leanne V. Wicker 1,2, Amanda Lamont 1, Chris Banks 1, Michelle Lang 3, Michael Lynch 4, Bonnie McMeekin 5, Kimberly A. Miller 2, Fiona Ryan 1, Katherine E. Selwood 1, Sally L. Sherwen 1 and Craig Whiteford 1 1 Wildlife Conservation and Science, Zoos Victoria, Parkville, VIC 3052, Australia; [email protected] (L.V.W.); [email protected] (A.L.); [email protected] (C.B.); [email protected] (F.R.); [email protected] (K.E.S.); [email protected] (S.L.S.); [email protected] (C.W.) 2 Healesville Sanctuary, Badger Creek, VIC 3777, Australia; [email protected] 3 Marketing, Communications & Digital Strategy, Zoos Victoria, Parkville, VIC 3052, Australia; [email protected] 4 Melbourne Zoo, Parkville, VIC 3052, Australia; [email protected] 5 Werribee Open Range Zoo, Werribee, VIC 3030, Australia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Simple Summary: In the summer of 2019–2020, a series of more than 15,000 bushfires raged across Citation: Parrott, M.L.; Wicker, L.V.; Australia in a catastrophic event called Australia’s Black Summer. An estimated 3 billion native Lamont, A.; Banks, C.; Lang, M.; animals, and whole ecosystems, were impacted by the bushfires, with many endangered species Lynch, M.; McMeekin, B.; Miller, K.A.; pushed closer to extinction. Zoos Victoria was part of a state-led bushfire response to assist wildlife, Ryan, F.; Selwood, K.E.; et al. -

What Role Does Ecological Research Play in Managing Biodiversity in Protected Areas? Australia’S Oldest National Park As a Case Study

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The University of Sydney: Sydney eScholarship Journals online What Role Does Ecological Research Play in Managing Biodiversity in Protected Areas? Australia’s Oldest National Park as a Case Study ROSS L. GOLDINGAY School of Environmental Science & Management, Southern Cross University, Lismore, NSW 2480 Published on 3 September 2012 at http://escholarship.library.usyd.edu.au/journals/index.php/LIN Goldingay, R.L. (2012). What role does ecological research play in managing biodiversity in protected areas? Australia’s oldest National Park as a case study. Proceedings of the Linnean Society of New South Wales 134, B119-B134. How we manage National Parks (protected areas or reserves) for their biodiversity is an issue of current debate. At the centre of this issue is the role of ecological research and its ability to guide reserve management. One may assume that ecological science has suffi cient theory and empirical evidence to offer a prescription of how reserves should be managed. I use Royal National Park (Royal NP) as a case study to examine how ecological science should be used to inform biodiversity conservation. Ecological research relating to reserve management can be: i) of generic application to reserve management, ii) specifi c to the reserve in which it is conducted, and iii) conducted elsewhere but be of relevance due to the circumstances (e.g. species) of another reserve. I outline how such research can be used to inform management actions within Royal NP. I also highlight three big challenges for biodiversity management in Royal NP: i) habitat connectivity, ii) habitat degradation and iii) fi re management.