Author(S): Title: Year

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Conference 2017.Indd

SCOTTISH GREENS AUTUMN CONFERENCE 2017 CONFERENCE LEADING THE CHANGE 21-22 October 2017 Contents 3. Welcome to Edinburgh 24. Sunday timetable 4. Welcome to Conference 26. Running order: Sunday 5. Guest speakers 28. Sunday events listings 6. How Conference works 32. Exhibitor information 10. Running order: Saturday 36. Venue maps 12. Child protection 40. Get involved! 13. Saturday events listings 41. Conference song 22. Saturday timetable 42. Exhibitor information Welcome to Edinburgh! I am pleased to be able to welcome you to the beautiful City of Edinburgh for the Scottish Green Party Autumn Conference. It’s been a challenging and busy year: firstly the very successful Local Council Elections, and then the snap General Election to test us even further. A big thank you to everyone involved. And congratulations – we have made record gains across the country electing more councillors than ever before! It is wonderful to see that Green Party policies have resonated with so many people across Scotland. We now have an opportunity to effect real change at a local level and make a tangible difference to people’s lives. At our annual conference we are able to further develop and shape our policies and debate the important questions that form our Green Party message. On behalf of the Edinburgh Greens, welcome to the Edinburgh Conference. Evelyn Weston, Co-convenor Edinburgh Greens 3 Welcome to our 2017 Autumn Conference! Welcome! We had a lot to celebrate at last year’s conference, with our best Holyrood election in more than a decade. This year we’ve gone even further, with the best council election in our party’s history. -

Business Bulletin Iris Ghnothaichean

Monday 26 July 2021 Business Bulletin Iris Ghnothaichean Today's Business Meeting of the Parliament Committee Meetings There are no meetings today. There are no meetings today. Monday 26 July 2021 1 Today's Business Future Business Motions & Questions Legislation Other Gnothaichean an-diugh Gnothaichean ri teachd Gluasadan agus Ceistean Reachdas Eile Chamber | Seòmar Meeting of the Parliament There are no meetings today. Monday 26 July 2021 2 Today's Business Future Business Motions & Questions Legislation Other Gnothaichean an-diugh Gnothaichean ri teachd Gluasadan agus Ceistean Reachdas Eile Committees | Comataidhean Committee Meetings There are no meetings today. Monday 26 July 2021 3 Today's Business Future Business Motions & Questions Legislation Other Gnothaichean an-diugh Gnothaichean ri teachd Gluasadan agus Ceistean Reachdas Eile Chamber | Seòmar Future Meetings of the Parliament Business Programme agreed by the Parliament on 23 June 2021 Tuesday 31 August 2021 2:00 pm Time for Reflection followed by Parliamentary Bureau Motions followed by Topical Questions (if selected) followed by First Minister’s Statement: Programme for Government 2021-22 followed by Committee Announcements followed by Business Motions followed by Parliamentary Bureau Motions 5:00 pm Decision Time followed by Members' Business Wednesday 1 September 2021 2:00 pm Parliamentary Bureau Motions 2:00 pm Portfolio Questions followed by Scottish Government Debate: Programme for Government 2021-22 followed by Business Motions followed by Parliamentary Bureau Motions -

Thomson Revised 20 09 17

Citation for published version: Thomson, J 2017, 'Abortion Law and Scotland: An Issue of What?', Political Quarterly. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-923X.12443 DOI: 10.1111/1467-923X.12443 Publication date: 2017 Document Version Peer reviewed version Link to publication University of Bath Alternative formats If you require this document in an alternative format, please contact: [email protected] General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 30. Sep. 2021 Abortion Law and Scotland: an issue of what? In recent years, two abrupt decisions have been taken at Westminster regarding abortion provision in the devolved regions of the United Kingdom. In 2017, following the general election and the Conservative-DUP supply and demand agreement, the British government declared that Northern Irish women who sought abortions in England would have their procedures funded on the NHS.i In 2015, the Conservative government devolved laws on abortion in Scotland to the Scottish government in Edinburgh. This article focuses on the second of these decisions – the resolution to devolve abortion laws to Scotland. It explores debates and documents produced at the time, asking why this decision was taken. Two debates on the issue of Scotland and abortion at Westminster are considered, alongside several questions on the issue put in the Scottish Parliament. -

TRI00000086 C Witness Statement

Edinburgh Tram Inquiry Office Use Only Witness Name: Gordon Mackenzie Dated: The Edinburgh Tram Inquiry Witness Statement of Gordon Ferguson Mackenzie Statement taken by Duncan Begg. My full name is Gordon Ferguson Mackenzie. I am aged 53, my date of birth being -· My contact details are known to the Inquiry. My current occupation is as a Social Work Manager. My role in the tram project was as Councillor with the City of Edinburgh Council (CEC). In 2007, I was a Director of I Transport for Edinburgh Ltd (TEL) and, in 2009; I became a member of the Tram t I Project Board (TPB). I have provided a copy of my curriculum vitae [CVS00000024]. ~ I Statement: I Introduction I' 1. In May 2003, I was elected as a Councillor for the Ward of Prestonfield as a Scottish Liberal Democrat, and I served until May 2007. In May 2007, there was an electoral reorganisation, as a result of which I served as a Scottish Liberal Democratic Councillor for the Ward of Southside and Newington until May 2012. Between 2003 and 2007, I held a number of positions in opposition, mainly to do with housing. 2. Prior to 2007, I do not recall that I had any particular involvement or direct relationship with the tram project. From 2007 onwards, however, I was a member of the CEC administration. From May 2007 to June 2009, I was the Convenor of Finance. From June 2009 to May 2012, I was Convenor of Transport. As a result of holding the Convenor of Finance role, I was Page 1 of 1 TRI00000086 _ C_ 0001 nominated to be a Director of Transport Edinburgh Limited (TEL). -

Scottish Leftreview

ScottishLeft Review Issue 113 September/October 2019 - £2.00 'best re(a)d' 'best 1 - ScottishLeftReview Issue 113 September/October 2019 ASLEF CALLS FOR AN INTEGRATED, PUBLICLY OWNED, ACCOUNTABLE RAILWAY FOR SCOTLAND (which used to be the SNP’s position – before they became the government!) Mick Whelan Tosh McDonald Kevin Lindsay General Secretary President Scottish Ocer ASLEF the train drivers union- www.aslef.org.uk STUC 2018_Layout 1 09/01/2019 10:04 Page 1 Britain’s specialist transport union Campaigning for workers in the rail, maritime, offshore/energy, bus and road freight sectors NATIONALISE SCOTRAIL www.rmt.org.uk 2 - ScottishLeftReview Issue 113 September/OctoberGeneral 2019Secretary: Mick Cash President: Michelle Rodgers feedback comment Like many others, Scottish Left Review is outraged at the attack on democracy represented by prorogation and condemns this extended suspension of Parliament to allow for a no-deal Brexit to be forced through without any parliamentary scrutiny or the opportunity for parliamentary opposition. Scottish Left Review supports initiatives to mobilise citizens outside of Parliament to confront this anti-democratic outrage. We call on all opposition MPs and Tory MPs who believe in parliamentary democracy to join together to defeat this outrage. All the articles in this issue (bar Kick up the Tabloids) were written before reviewsthe prorogation on 28 August 2019. t has long been a shibboleth on the Who will benefit from Brexit? of contradictions. This is certainly true radical left, following from Marx and as Boris seems to be prepared to engage In the lead article in this issue, George Engels, that politics in the last instance in Keynesian-style reflation to try to aid I Kerevan explains this perplexing situation bends to the will of economics. -

The City of Edinburgh Council Year 2008/2009

Committee Minutes The City of Edinburgh Council Year 2008/2009 Meeting 14 – Thursday 30 April 2009 Edinburgh, 30 April 2009 - At a meeting of The City of Edinburgh Council. Present:- LORD PROVOST The Right Honourable George Grubb COUNCILLORS Elaine Aitken Alison Johnstone Ewan Aitken Colin Keir Robert C Aldridge Louise Lang Jeremy R Balfour Jim Lowrie Eric Barry Gordon Mackenzie David Beckett Kate MacKenzie Angela Blacklock Marilyne A MacLaren Mike Bridgman Mark McInnes Deidre Brock Stuart Roy McIvor Gordon Buchan Tim McKay Tom Buchanan Eric Milligan Steve Burgess Elaine Morris Andrew Burns Joanna Mowat Ronald Cairns Rob Munn Steve Cardownie Gordon J Munro Maggie Chapman Ian Murray Maureen M Child Alastair Paisley Joanna Coleman Gary Peacock Jennifer A Dawe Ian Perry Charles Dundas Cameron Rose Cammy Day Jason G Rust Paul G Edie Conor Snowden Nick Elliott-Cannon Marjorie Thomas Paul Godzik Stefan Tymkewycz Norma Hart Phil Wheeler Stephen Hawkins Iain Whyte Ricky Henderson Donald Wilson Lesley Hinds Norrie Work Allan G Jackson 2 The City of Edinburgh Council 30 April 2009 1 The Quality Standard Award The Lord Provost and members of the Council congratulated five schools in achieving the Quality Standard Award in the most recent round of applications. The Lord Provost presented the award to the following schools in recognition of their achievements: • Clovenstone Primary School • East Craigs Primary School • Fox Covert Primary School • Gracemount High School • James Gillespie’s High School (Reference – report no CEC/171/08-09 by the Director of Children and Families, submitted.) 2 Youngedinburgh: Presentation by Local Youth Forums Youngedinburgh, the Council’s Youth Services Strategy, aimed to improve the quality of life of the city’s young people aged 11-21 years. -

Under Equality's Sun: George Mackay Brown and Socialism from the Margins of Society

MacBeath, Stuart (2018) Under Equality's Sun: George Mackay Brown and socialism from the margins of society. MPhil(R) thesis. https://theses.gla.ac.uk/8871/ Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten: Theses https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Under Equality’s Sun George Mackay Brown and Socialism from the Margins of Society Stuart MacBeath, B.A. (Hons), PGDE A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Philosophy (Research) Scottish Literature School of Critical Studies College of Arts University of Glasgow October 2017 1 Contents Acknowledgements 3 Abstract 4 Abbreviations 5 Introduction 6 Chapter One 13 ‘Grief by the Shrouded Nets’ –Brown’s Orcadian, British and Universal Background Chapter Two 33 ‘The Tillers of Cold Horizons’: Brown’s Early Political Journalism Chapter Three 58 ‘Puffing Red Sails’ – The Progression of Brown’s Journalism Chapter Four 79 ‘All Things Wear Now to a Common Soiling’ – Placing Brown’s Politics Within His Short Fiction Conclusion 105 ‘Save that Day for Him’: Old Ways of Living in New Times – Further Explorations of Brown’s Politics Appendices Appendix One - ‘Why Toryism Must Fail’ 117 Appendix Two - ‘Think Before You Vote’ 118 Appendix Three – ‘July 26th in Stromness’ 119 Appendix Four - The Uncollected Early Journalism of George Mackay Brown 120 2 Bibliography 136 3 Acknowledgments I would first like to thank my supervisor, Professor Kirsteen McCue, for her guidance, support and enthusiasm throughout the construction of this project. -

Council Results 2007

Aberdeen 2007 Elected Councillors Ward 1: Dyce, Bucksburn & Danestone Ron Clark (SLD) Barney Crockett (Lab) Mark McDonald (SNP) George Penny (SLD) Ward 2: Bridge of Don Muriel Jaffrey (SNP) Gordon Leslie (SLD) John Reynolds (SLD) Willie Young (Lab) Ward 3 Kingswells & Sheddocksley Len Ironside (Lab) Peter Stephen (SLD) Wendy Stuart (SNP) Ward 4 Northfield Jackie Dunbar (SNP) Gordon Graham (Lab) Kevin Stewart (SNP) Ward 5 Hilton / Stockethill George Adam (Lab) Neil Fletcher (SLD) Kirsty West (SNP) Ward 6 Tillydrone, Seatonand Old Aberdeen Norman Collie (Lab) Jim Noble (SNP) Richard Robertson (SLD) Ward 7 Midstocket & Rosemount BIll Cormie (SNP) Jenny Laing (Lab) John Porter (Con) Ward 8 George St & Harbour Andrew May (SNP) Jim Hunter (Lab) John Stewart (SLD) Ward 9 Lower Deeside Marie Boulton (Ind) Aileen Malone (SLD) Alan Milne (Con) Ward 10 Hazelhead, Ashley and Queens Cross Jim Farquharson (Con) Martin Grieg (SLD) Jennifer Stewart (SLD) John West (SNP) Ward 11 Airyhall, Broomhill and Garthdee Scott Cassie (SLD) Jill Wisely (Con) Ian Yuill (SLD) Ward 12 Torry & Ferryhill Yvonne Allan (Lab) Irene Cormack (SLD) Alan Donnelly (Con) Jim Kiddie (SNP) Ward 13 Kincorth & Loirston Neil Cooney (Lab) Katherine Dean (SLD) Callum McCaig (SNP) ELECTORATE: 160,500 2003 RESULT: SLD 20: Lab 14: SNP 6: Con 3 Aberdeenshire 2007 Elected Councillors Ward 1 Banff and District John B Cox (Ind) Ian Winton Gray (SNP) Jack Mair (SLD) Ward 2 Troup Mitchell Burnett (SNP) John Duncan (Con) Sydney Mair (Ind) Ward 3 Fraserburgh and District Andy Ritchie (SNP) Ian -

Scottish Parliament Election Declaration of Constituency Result

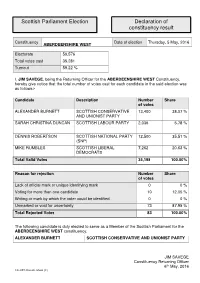

Scottish Parliament Election Declaration of constituency result Constituency Date of election Thursday, 5 May, 2016 ABERDEENSHIRE WEST Electorate 59,576 Total votes cast 35,281 Turnout 59.22 % I, JIM SAVEGE , being the Returning Officer for the ABERDEENSHIRE WEST Constituency, hereby give notice that the total number of votes cast for each candidate in the said election was as follows:- Candidate Description Number Share of votes ALEXANDER BURNETT SCOTTISH CONSERVATIVE 13,400 38.07 % AND UNIONIST PARTY SARAH CHRISTINA DUNCAN SCOTTISH LABOUR PARTY 2,036 5.78 % DENNIS ROBERTSON SCOTTISH NATIONAL PARTY 12,500 35.51 % (SNP) MIKE RUMBLES SCOTTISH LIBERAL 7,262 20.63 % DEMOCRATS Total Valid Votes 35,198 100.00 % Reason for rejection Number Share of votes Lack of official mark or unique identifying mark 0 0 % Voting for more than one candidate 10 12.05 % Writing or mark by which the voter could be identified 0 0 % Unmarked or void for uncertainty 73 87.95 % Total Rejected Votes 83 100.00 % The following candidate is duly elected to serve as a Member of the Scottish Parliament for the ABERDEENSHIRE WEST constituency: ALEXANDER BURNETT SCOTTISH CONSERVATIVE AND UNIONIST PARTY JIM SAVEGE Constituency Returning Officer 6th May, 2016 Ct5-SPC-Results Sheet (C) Scottish Parliament Election Declaration of regional votes cast in a constituency Constituency ABERDEEN SHIRE WE ST Date of election Thursday 5 May 2016 Electorate 59,576 Total votes cast 35,274 Turnout 59.21 % I, JIM SAVEGE , being the Returning Officer for the ABERDEENSHIRE WEST Constituency, -

Separatism and Regionalism in Modern Europe

Separatism and Regionalism in Modern Europe Separatism and Regionalism in Modern Europe Edited by Chris Kostov Logos Verlag Berlin λογος Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de . Book cover art: c Adobe Stock: Silvio c Copyright Logos Verlag Berlin GmbH 2020 All rights reserved. ISBN 978-3-8325-5192-6 The electronic version of this book is freely available under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 licence, thanks to the support of Schiller University, Madrid. Logos Verlag Berlin GmbH Georg-Knorr-Str. 4, Gebäude 10 D-12681 Berlin - Germany Tel.: +49 (0)30 / 42 85 10 90 Fax: +49 (0)30 / 42 85 10 92 https://www.logos-verlag.com Contents Editor's introduction7 Authors' Bios 11 1 The EU's MLG system as a catalyst for separatism: A case study on the Albanian and Hungarian minority groups 15 YILMAZ KAPLAN 2 A rolling stone gathers no moss: Evolution and current trends of Basque nationalism 39 ONINTZA ODRIOZOLA,IKER IRAOLA AND JULEN ZABALO 3 Separatism in Catalonia: Legal, political, and linguistic aspects 73 CHRIS KOSTOV,FERNANDO DE VICENTE DE LA CASA AND MARÍA DOLORES ROMERO LESMES 4 Faroese nationalism: To be and not to be a sovereign state, that is the question 105 HANS ANDRIAS SØLVARÁ 5 Divided Belgium: Flemish nationalism and the rise of pro-separatist politics 133 CATHERINE XHARDEZ 6 Nunatta Qitornai: A party analysis of the rhetoric and future of Greenlandic separatism 157 ELLEN A. -

No. 47, September 2018

1 No. 47, September 2018 Editors: L. Görke – Prof. Dr. K. P. Müller – R. Walker Scottish Studies Newsletter 47, September 2018 2 Table of Contents Scottish Studies Newsletter 47, Sept 2018 Editorial 3 Scotland and the Turmoil of Brexit - A. L. Kennedy, "A toxic culture" 6 - Iain MacWhirter, "How to win Indyref 2? Keep it simple" 8 - "Sir Ivan Rogers' letter to staff in full" 11 Exchange students' reports - Josip Brekalo / Marco Giovanazzi, 14 "People make Glasgow" - A report from the perspective of two exchange students - Simona Hildebrand, "Fuireach anns an Dùn Eideann – Living in Edinburgh" 15 - Marsida Toska, "Edinburgh, my Love!" 16 - Jessica Völkel, "Autumn in Edinburgh" 18 Britain after the Brexit Decision Klaus Peter Müller, "The State of Britain 2018 - 2021: All Out War and Overall Bankruptcy" 19 Common Weal, "Scottish National Investment Bank Success" 41 New Scottish Poetry: Peter McCarey 43 Ian McGhee (Secretary, The John Galt Society), John Galt – Observer and Recorder 43 Stewart Whyte, Swithering Whytes or What to do with a troublesome cat? 47 (New) Media on Scotland 49 Education Scotland 104 Scottish Award Winners 114 New Publications March 2016 – February 2018 114 Book Reviews Peter Auger on Barbour's 'Bruce' and its Cultural Contexts 135 Chelsea Hartlen on Women and Violent Crime in Enlightenment Scotland 137 Richie McCaffery on Scotland in Europe / Europe in Scotland: … 139 James M. Morris on Facts and Inventions: Selections from the Journalism of J. Boswell 140 Klaus Peter Müller on Sir Walter Scott. A Life in Story 142 Carla Sassi on Opium and Empire: The Lives and Careers of W. -

Scottish Green Party Submission to Smith Commission on Devolution Patrick Harvie MSP and Cllr Maggie Chapman, SGP Co-Convenors

Scottish Green Party submission to Smith Commission on Devolution Patrick Harvie MSP and Cllr Maggie Chapman, SGP Co-Convenors Introduction The Scottish Green Party welcomes the opportunity to contribute to the debate on the future of devolution, given that the people of Scotland chose by majority to vote No in the independence referendum. Though we campaigned for a Yes vote in the referendum and are naturally disappointed at the result, we believe that a window of opportunity remains open for change. It is in the nature of Green politics to seek ways of working constructively with others; neither downplaying our differences nor allowing them to prevent us from finding common ground where possible. However it should be noted that this will not be an easy task on the timescale which has been imposed. If it is to be achieved then there will need to be willingness on both sides of the independence divide to give ground. The scope for compromise Those who campaigned for a Yes vote will need to accept that the current process will not realise our ambitions for independence. We respect the decision the majority of voters made, even if we regard it as a missed opportunity. Those who campaigned for a No vote will also need to acknowledge that the commitments made in the final stages of the referendum campaign went significantly beyond the proposals published by Labour, the Liberal Democrats and the Conservatives earlier in the year. There is clear evidence from recent opinion polling that a majority in Scotland would support the devolution of “all areas of government policy except for defence and foreign affairs, which is sometimes referred to as devo max”.