Mozart & Brahms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fiery Pianist Khatia Buniatishvili Makes Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra Debut in Lilly Classical Series Concerts Jan

Date: Monday, January 16, 2012 Contact: Tim Northcutt – (317) 262-4904 Jessica Di Santo – (317) 229-7082 Fiery Pianist Khatia Buniatishvili Makes Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra Debut in Lilly Classical Series Concerts Jan. 26-28 at Clowes Memorial Hall 2008 Arthur Rubinstein Competition prize winner performs Rachmaninoff Second Piano Concerto INDIANAPOLIS – As one of the fast-rising young stars in classical music, pianist Khatia Buniatishvili will make her Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra debut in performances of Sergei Rachmaninoff’s passionate and colorful Second Piano Concerto to highlight Lilly Classical Series concerts Thursday through Saturday, January 26-28, at Clowes Memorial Hall, located at 4602 Sunset Avenue on the Butler University campus. Originally scheduled for the Hilbert Circle Theatre, the venue change was prompted by the needs of the National Football League and the Indianapolis Super Bowl XLVI Committee to reserve large venues in the downtown area that are capable of hosting various Super Bowl events and activities. Preparations to host NBC’s Live with Jimmy Fallon during Super Bowl week will be underway at the ISO’s home that weekend. This all-Russian classical weekend, conducted by Princeton Symphony Orchestra Music Director Rossen Milanov, will open with Dmitri Shostakovich’s Festive Overture, a light and celebratory piece that the composer wrote to mark the anniversary of the Bolshevik overthrow of the Russian government in 1917. Buniatishvili will introduce herself to Indianapolis audiences in performances of one of the crown jewels of the piano repertoire, Sergei Rachmaninoff’s popular Second Piano Concerto. This glittering and melodic work showcases the technical artistry of the soloist with many rhapsodic moments spotlighting the pianist. -

SHEDDING LIGHT on BULGARIAN SYMPHONY ORCHESTRAS /PIANO Or FORTЕ

SHEDDING LIGHT ON BULGARIAN SYMPHONY ORCHESTRAS /PIANO or FORTЕ/ Brief historic notes Orchestral music-making in Bulgaria goes back to mid-nineteenth century when in the Northeastern, multilingual town of Shumen the first ensemble was founded. It had entertainment and promotional purposes rather than serious concert activities. The significance of the ensemble though is mainly in the first establishment of a repertoire (Bulgarian and foreign) which was suitable for performance, as well as bringing together professionally educated national musicians and music-makers. Over WW2 orchestras developed in Bulgaria in lows and peaks. Those days gave rise to the Guards Orchestra (1892) conducted by Joseph Hohola; the Academic Symphony Orchestra (1928) and the Royal Military Symphony Orchestra (1936)both founded in Sofia by Prof. Sasha Popov; the State Philharmonic Orchestra at the National Opera (1935). At concerts in Bulgaria and abroad they perform major works by national and international musical classics. These ensembles invited outstanding guest conductors and soloists – Fausto Magnani, Karl Bohm, Bruno Walter, Edmondo de Vecchi, Emil Kupper, Carlo Zecchi, Henry Marteau, Paul Wittgenstein, Dinu Lipatti etc. After the end of the war the dynamic history of Bulgarian orchestras included both the above listed and numerous new ensembles founded all over the country. The Sofia Philharmonic Orchestra continued the tradition of the Sofia-based ensembles. The Philharmonic has performed with conductors Konstantin Iliev, Dobrin Petkov, Vassil Stefanov, Vladi Simeonov, Dimitar Manolov, Yordan Dafov, Emil Tabakov etc. At approximately the same time the capital saw the rise and establishment of yet another outstanding ensemble – the Symphony Orchestra of the Bulgarian National Radio (1948). -

Ning Fengviolin Virtuosismo

CHANNEL CLASSICS CCS 40719 NING FENG VIOLIN PAGANINI&VIEUXTEMPS VIRTUOSISMO ORQUESTA SINFÓNICA DEL PRINCIPADO DE ASTURIAS ROSSEN MILANOV CONDUCTOR Ning Feng (photo: Lawrence Tsang) 2 NING FENG returns to the Shanghai Symphony Orchestra under the baton of Yu Long. “Ning Feng’s total mastery could be seen in the In recital and chamber music Ning Feng precision and sweep of his bow, and heard in the regularly performs with Igor Levit and Daniel effortless tonal range, from sweet to sumptuous.” Müller-Schott, amongst others, and in 2012 New Zealand Herald - founded the Dragon Quartet. He appears at major venues and festivals such as the Wigmore Hall in Ning Feng is recognised internationally as an artist London, the Concertgebouw Amsterdam, National of great lyricism, innate musicality and stunning Centre for Performing Arts (Beijing) as well as the virtuosity. Blessed with an impeccable technique Schubertiade, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern and Hong and a silken tone, his palette of colours ranges from Kong International Chamber Music Festivals. intimate delicacy to a ferocious intensity. The Berlin Born in Chengdu, China, Ning Feng studied at based Chinese violinist performs across the globe the Sichuan Conservatory of Music, the Hanns Eisler with major orchestras and conductors, in recital School of Music (Berlin) with Antje Weithaas and and chamber concerts. the Royal Academy of Music (London) with Hu Kun Recent successes have included a return to where he was the first student ever to be awarded the Budapest Festival Orchestra with Iván Fischer -

Haochen Zhang Bio | the Philadelphia Orchestra

Haochen Zhang Piano 2019 Tour of China Since his gold medal win at the Thirteenth Van Cliburn International Piano Competition in 2009, Haochen Zhang has captivated audiences in the United States, Europe, and Asia. In 2017 he received the prestigious Avery Fisher Career Grant. He has already appeared with many of the world’s leading festivals and orchestras including the BBC Proms; the China, Munich, London, Los Angeles, Israel, and Hong Kong philharmonics; the Easter Festival in Moscow; the London, San Francisco, Seattle, Singapore, and Sydney symphonies; the Mariinsky Orchestra; and the NDR Sinfonieorchester. He made his Philadelphia Orchestra debut in 2006 as a winner of the Orchestra’s Albert M. Greenfield Student Competition. Mr. Zhang is also an avid chamber musician, collaborating with colleagues such as the Shanghai Quartet, the Tokyo Quartet, the Brentano Quartet, violinist Benjamin Beilman, and cellist Aurélien Pascal. He is frequently invited by chamber music festivals in the United States including the Santa Fe Chamber Music Festival and La Jolla Summerfest. Highlights of the 2018-19 season included his debut with the Lucerne Festival Orchestra and performances with the National, Hong Kong, and China philharmonics; the San Angelo, Guangzhou, Shanghai, and Spokane symphonies; and recitals in Berlin, Paris, Madrid, Lucerne, and Brussels, among others. Mr. Zhang has recorded a recital CD, released by BIS Records in February 2017, which includes works by Schumann, Brahms, Janacek, and Liszt. He gave extensive recital and concerto tours in Asia with performances in China, Hong Kong, and Japan. In October 2017, Haochen gave a concerto performance at Carnegie Hall with the NCPA Orchestra, which was followed by his recital debut at Carnegie’s Zankel Hall. -

Foundation for Chinese Performing Arts 中華表演藝術基金會

中華表演藝術基金會 FOUNDATION FOR CHINESE PERFORMING ARTS [email protected] www.ChinesePerformingArts.net The Foundation for Chinese Performing Arts, is a non-profit organization registered in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts in January, 1989. The main objectives of the Foundation are: * To enhance the understanding and the appreciation of Eastern heritage through music and performing arts. * To promote Chinese music and performing arts through performances. * To provide opportunities and assistance to young Asian artists. The Founder and the President is Dr. Catherine Tan Chan 譚嘉陵. AWARDS AND SCHOLARSHIPS The Foundation held its official opening ceremony on September 23, 1989, at the Rivers School in Weston. Professor Chou Wen-Chung of Columbia University lectured on the late Alexander Tcherepnin and his contribution in promoting Chinese music. The Tcherepnin Society, represented by the late Madame Ming Tcherepnin, an Honorable Board Member of the Foundation, donated to the Harvard Yenching Library a set of original musical manuscripts composed by Alexander Tcherepnin and his student, Chiang Wen-Yeh. Dr. Eugene Wu, Director of the Harvard Yenching Library, was there to receive the gift that includes the original orchestra score of the National Anthem of the Republic of China commissioned in 1937 to Alexander Tcherepnin by the Chinese government. The Foundation awarded Ms. Wha Kyung Byun as the outstanding music educator. In early December 1989, the Foundation, recognized Professor Sylvia Shue-Tee Lee for her contribution in educating young violinists. The recipients of the Foundation's artist scholarship award were: 1989 Jindong Cai 蔡金冬, MM conductor ,New England Conservatory, NEC (currently conductor and Associate Professor of Music, Stanford University,) 1990: (late) Pei-Kun Xi, MM, conductor, NEC; 1991: pianists John Park and J.G. -

August 8-16 2019 August 15 2019

www.kirovmusicfestival.org August 8-16 2019 Kirov Academy of Washington D.C. August 15 2019 The Kennedy Center Family Theater KIROV ACADEMY of MUSIC | 2 The Kirov Academy is dedicated to artistic and academic excellence and to instilling a moral education in our students. Founded 30 years ago in Northeast D.C. on universal principles of love, respect, and service, Kirov Academy believes in the importance of the arts and culture in creating a world of beauty and effectuating positive change. This year marks the inaugural occurrence of the Kirov International Music Festival and Competition, Washington, D.C.’s most significant new competition and festival. Marking the commencement of the Kirov Academy’s ongoing collaboration with the Moscow Conservatory and the debut of its new Music Department, the Kirov International Music Festival has brought students and instructors from across the globe to participate in master classes with internationally renowned musicians and masters, and to be given the opportunity to compete with their talented and dedicated peers. In addition to performing at the Kennedy Center, competition winners have been extended an invitation to perform at the Moscow Conservatory. KIROV ACADEMY of MUSIC | 3 PRESIDENT Message Distinguished Friends and Patrons of the Arts, The Kirov Academy is honored to host the 1st Kirov International Music Festival and Competition in the heart of Washington DC. Our new initiative aims to connect tomorrow’s talent with a global family of outstanding musicians who are engaged in creating a world of beauty and effectuating positive change through the arts. The Kirov International Music Festival and Competition builds on the foundation of the celebrated Kirov Academy of Ballet that enjoys a 30 year tradition synonymous with Russian excellence. -

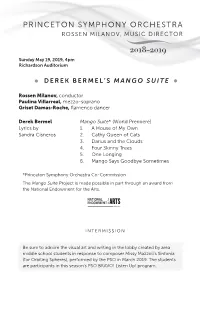

Mango Suite Program Pages

PRINCETON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA ROSSEN MILANOV, MUSIC DIRECTOR 2018–2019 Sunday May 19, 2019, 4pm Richardson Auditorium DEREK BERMEL’S MANGO SUITE Rossen Milanov, conductor Paulina Villarreal, mezzo-soprano Griset Damas-Roche, flamenco dancer Derek Bermel Mango Suite* (World Premiere) Lyrics by 1. A House of My Own Sandra Cisneros 2. Cathy Queen of Cats 3. Darius and the Clouds 4. Four Skinny Trees 5. One Longing 6. Mango Says Goodbye Sometimes *Princeton Symphony Orchestra Co-Commission The Mango Suite Project is made possible in part through an award from the National Endowment for the Arts. INTERMISSION Be sure to admire the visual art and writing in the lobby created by area middle school students in response to composer Missy Mazzoli’s Sinfonia (for Orbiting Spheres), performed by the PSO in March 2019. The students are participants in this season’s PSO BRAVO! Listen Up! program. Manuel de Falla El amor brujo Introducción y escena (Introduction and Scene) En la cueva (In the Cave) Canción del amor dolido (Song of Love’s Sorrow) El Aparecido (The Apparition) Danza del terror (Dance of Terror) El círculo mágico (The Magic Circle) A medianoche (Midnight) Danza ritual del fuego (Ritual Fire Dance) Escena (Scene) Canción del fuego fatuo (Song of the Will-o’-the-Wisp) Pantomima (Pantomime) Danza del juego de amor (Dance of the Game of Love) Final (Finale) El sombrero de tres picos (The Three-Cornered Hat), Suite No. 1 Introduction—Afternoon Dance of the Miller’s Wife (Fandango) The Corregidor The Grapes La vida breve, Spanish Dance No. 1 This concert is made possible in part through the support of Yvonne Marcuse. -

GEORGIEV Martin

MARTIN GEORGIEV’s artistic activity connects the fields of composition, conducting and research in a symbiosis. As a composer and conductor he has collaborated with leading orchestras and ensembles, such as the Brussels Philharmonic, BBC Symphony Orchestra, Bulgarian National Radio Orchestra, Heidelberg Philharmonic Orchestra, Sofia National Philharmonic Orchestra, National Orchestra of Belgium, Azalea Ensemble, Manson Ensemble, Cosmic Voices choir, Isis Ensemble and Ensemble Musiques Nouvelles. More recently he was Composer in Residence to the City of Heidelberg - 'Komponist für Heidelberg 2012|13", featuring the orchestral commission The Secret which premiered in 2013 with the Heidelberg Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by the composer. Since 2013 he works as Assistant Conductor for the Royal Ballet at ROH Covent Garden, London, where he is involved with a number of world premieres. In 2010-11 he was SAM Embedded Composer with the BBC Symphony Orchestra, London. He has completed a PhD doctorate in Composition at the Royal Academy of Music, University of London (2012), in which he developed his Morphing Modality technique for composition. He also holds Masters' degrees in both Composition and Conducting from the Royal Academy of Music and the National Academy of Music 'Pancho Vladigerov', Sofia, Bulgaria. Born in 1983 at Varna, Bulgaria, he is based in London since 2005, holding both Bulgarian and British citizenship. He is a laureate of the International Composers' Forum TACTUS in Brussels, Belgium, where his works featured in the selection in 2004, 2008 and 2011; the Grand Prize for Symphonic Composition dedicated to the 75th Anniversary of the Sofia National Philharmonic Orchestra in 2003; the UBC Golden Stave Award in 2004; orchestral commission prize in memory of Sir Henry Wood by the Royal Academy of Music, London, in 2011; he was a finalist of the Hindemith Prize of the Schleswig-Holstein Music Festival in Germany in 2011 and a recipient of 15 prizes from national and international competitions as a percussionist. -

Edition 4 | 2019-2020

A Message from the Chair of the Board of Trustees 4 2020 Musician Roster 5 MARCH 6-7 11 Peaks of Beauty and Devotion MARCH 20-21 19 Beethoven at 250: An Apotheosis of Energy MARCH 27-28 27 The Rite of Spring APRIL 17-18 35 Beethoven at 250: The Ninth Symphony Spotlight on Education 50 Board of Trustees/Staff 51 Friends of the Columbus Symphony 53 Columbus Symphony League 54 Future Inspired 55 Partners in Excellence 57 Corporate and Foundation Partners 57 Individual Partners 58 In Kind 61 Tribute Gifts 61 Legacy Society 64 Concert Hall & Ticket Information 67 ADVERTISING Onstage Publications 937-424-0529 | 866-503-1966 e-mail: [email protected] www.onstagepublications.com The Columbus Symphony program is published in association with Onstage Publications, 1612 Prosser Avenue, Dayton, Ohio 45409. The Columbus Symphony program may not be reproduced in whole or in part without written permission from the publisher. Onstage Publications is a division of Just Business!, Inc. Contents © 2020. All rights reserved. Printed in the U.S.A. A MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIR OF THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES Dear Columbus Symphony Supporter, As our 2019–20 season comes to a close, we again thank you for your support of quality, live performances of orchestral music in our community! We are thrilled to end our season with four amazing performances. Our wonderful spring concerts start with Peaks of Beauty and Devotion (March 6–7, Ohio Theatre). American artist Joshua Roman performs his own evocative Cello Concerto in a CSO premiere. Rossen Milanov conducts this powerful performance, culminating in Anton Bruckner’s majestic Symphony No. -

2010-2011 Chamber Music Spotlight No. 1

LYNN PHILHARMONIA No. 5 Jon Robertson, guest conductor Saturday, Feb. 19 – 7:30 p.m.│Sunday, Feb. 20 – 4 p.m. Beethoven: Piano Concerto No. 5 in E-flat Major, op. 73 (“Emperor”): Roberta Rust, piano Dvorak: Symphony No. 6 in D Major, op. 60 Keith C. and Elaine Johnson Wold Performing Arts Center Box: $50 |Orchestra: $40 |Mezzanine: $35 COLLABORATIVE SPOTLIGHT: DUO PIANISTS LEONARD AND SHEN Thursday, Feb. 24 at 7:30 p.m. This project has been possible by the National Endowment for the Arts as part of American Masterpieces: Three Centuries of Artistic Genius. The inaugural collaborative spotlight event, piano faculty members Yang Shen and Lisa Leonard team up in a program featuring the most elegant and virtuosic repertoire for two pianos. Amarnick-Goldstein Concert Hall $20 or $93 for the entire series (a savings of 25%) INSTRUMENTAL COLLABORATIVE PIANO DEPARTMENTAL RECITAL Sunday, Feb. 27 at 4 p.m. Join us for this exciting inaugural event which will showcase the outstanding pianists of the collaborative studio with fellow students and faculty in a potpourri program celebrating the hallmarks of the duo and chamber repertoire. Amarnick-Goldstein Concert Hall $10 STRING CONCERT Chamber Music Thursday, March 3 at 7:30 p.m. An enjoyable evening of music featuring performances by Conservatory of Music string students. Hear violinists, violists, cellists and bassists chosen to showcase the conservatory’s outstanding string Spotlight No. 1 department. Amarnick-Goldstein Concert Hall $10 MOSTLY MUSIC: BEETHOVEN Thursday, March 10 at 7:30 p.m. Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)was born just 14 years after Mozart’s birth but a dramatic historical change was underway – the gradual decay of European aristocracy. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE December 5, 2019 LUNAR NEW

Lunar New Year / 1 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE December 5, 2019 LUNAR NEW YEAR CONCERT AND GALA Conducted by LONG YU US PREMIERE of ZHOU Tian’s Gift NEW YORK PREMIERE of Texu KIM’s Spin-Flip CHEN Gang and HE Zhanhao’s The Butterfly Lovers, Violin Concerto, with GIL SHAHAM GERSHWIN’s Rhapsody in Blue with HAOCHEN ZHANG January 28, 2020 The New York Philharmonic will celebrate the Lunar New Year, welcoming the Year of the Rat with a Concert and Gala on Tuesday, January 28, 2020, at 7:30 p.m. Long Yu will return to conduct the US Premiere of Zhou Tian’s Gift; the New York Premiere of Texu Kim’s Spin-Flip; Chen Gang and He Zhanhao’s The Butterfly Lovers, Violin Concerto, with Gil Shaham as soloist; and Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue, with pianist Haochen Zhang in his Philharmonic debut. The New York Philharmonic has welcomed the Lunar New Year with an annual celebration since 2012. Chinese American composer Zhou Tian’s Gift, written for Long Yu and the Shanghai Symphony Orchestra, reflects “my own musical identity after 18 years of living abroad.” Korean composer Texu Kim shares his name with a famous Korean table tennis player; Spin-Flip — the title of which alludes to both astrophysical phenomena and table tennis techniques — “conveys the driving energy of a (good) Ping-Pong match … its alternating harmonic pattern and somewhat random form reflect the alternation of service and unpredictable result, respectively.” American violinist Gil Shaham recorded The Butterfly Lovers, which reflects both Chinese and Western traditions and was banned during the Cultural Revolution, with the Singapore Symphony Orchestra in 2007. -

The Wanamaker Organ

MUSIC FOR ORGAN AND ORCHESTRA CTHeEn W AnN AiMaA k CERo OnRcGerA N PETER RICHARD CONTE, ORGAN SyMPHONy IN C • ROSSEN MIlANOv, CONDUCTOR tracklist Symphony No. 2 in A Major, for Organ and Orchestra, Opus 91 Félix Alexandre Guilmant 1|I. Introduction et Allegro risoluto 10:18 2|II. Adagio con affetto 5:56 3|III. Scherzo (Vivace) 6:49 4|IV. Andante Sostenuto 2:39 5|V. Intermède et Allegro Con Brio 5:55 6 Alleluja, for Organ & Orchestra, Opus 112 Joseph Jongen 5:58 7 Hymne, for Organ & Orchestra, Opus 78 Jongen 8:52 Symphony No. 6 in G Minor, for Organ and Orchestra, Opus 42b Charles-Marie Widor 8|I. Allegro Maestoso 9:21 9|II. Andante Cantabile 10:39 10 | III. Finale 6:47 TOTAL TIME : 73:16 2 3 the music FÉLIX ALEXANDRE GUILMANT Symphony No. 2 in A Major for Organ and Orchestra, Op. 91 Alexandre Guilmant (1837-1911), the renowned Parisian organist, teacher and composer, wrote this five- movement symphony in 1906. Two years before its composition, Guilmant played an acclaimed series of 40 recitals on the St. Louis World ’s Fair Organ —the largest organ in the world —before it became the nucleus of the present Wanamaker Organ. In the Symphony ’s first movement, Introduction et Allegro risoluto , a sprightly theme on the strings is offset by a deeper motif. That paves the way for the titanic entrance of full organ, with fugato expositions and moments of unbridled sensuousness, CHARLES-MARIE WIDOR building to a restless climax. An Adagio con affetto follows Symphony No 6 in G Minor in A-B-A form, building on the plaintive organ with silken for Organ and Orchestra, Op.