Adlittle.Com Prism / 1 / 2008

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Velcro Fasteners – What You Need to Know

Velcro Fasteners – What You Need to Know Among the fastening systems we offer for our removable insulation blankets is Velcro. An excellent and easy to use fastener, Velcro is often used in applications which require a simple and quick fastening method. Velcro fastening does, however, come with some limitations, which users need to be aware of in order for it to function as intended. Background – How it works: Velcro is actually the trade name for what is generically known as ‘Hook and Loop’ fastening. The hook‐and‐loop fastener was conceived in 1941 by Swiss engineer George de Mestral who lived in Commugny, Switzerland. The idea came to him one day after returning from a hunting trip with his dog in the Alps. He took a close look at the burrs (seeds) of burdock that kept sticking to his clothes and his dog's Tiny hooks can be seen fur. He examined them under a microscope, and noted covering the surface of this their hundreds of "hooks" that caught on anything with a burr loop, such as clothing, animal fur, or hair. He saw the possibility of binding two materials reversibly in a simple fashion if he could figure out how to duplicate the hooks and loops. It took de Mestral around 10 years to perfect the process, and Velcro was born.1 1 Wikepedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Velcro Velcro Fastening on Removable Insulation Blankets: Velcro fastening systems are supplied on rolls of paired woven tapes. The materials used in making these woven tapes are typically one or more of nylon, polyester, and Nomex (a flame‐resistant meta‐aramid material developed in the early 1960s by DuPont). -

TUNZA 2009 YOUTH CONFERENCES - What We Want from Copenhagen 2010 - INTERNATIONAL YEAR of BIODIVERSITY

The UNEP Magazine for Youth for young people · by young people · about young people TUNZA 2009 YOUTH CONFERENCES - What we want from Copenhagen 2010 - INTERNATIONAL YEAR OF BIODIVERSITY ‘We have to protect the Earth, not just for us but for future generations.’ Yugratna Srivastava at the UN High-Level Summit on Climate Change TUNZA the UNEP magazine CONTENTS for youth. To view current and past issues of this Editorial 3 publication online, please visit www.unep.org Big ask 4 United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) What next? 6 PO Box 30552, Nairobi, Kenya Tel (254 20) 7621 234 Fax (254 20) 7623 927 Trees, not words 7 Telex 22068 UNEP KE E-mail [email protected] www.unep.org Vote for a voice 8 ISSN 1727-8902 Meet the TYAC 8 Director of Publication Satinder Bindra Editor Geoffrey Lean Special Contributor Wondwosen Asnake Natural mimicry 10 Youth Editors Karen Eng, Joseph Lacey Nairobi Coordinator Naomi Poulton Head, UNEP’s Children and Youth Unit Nature’s R&D 11 Theodore Oben Circulation Manager Manyahleshal Kebede So you think we know it all? 12 Design Edward Cooper, Ecuador; Richard Lewis, Trinidad and Tobago Production Banson Keeping the pieces 14 Front cover photo UNEP Youth Contributors Shaikha Alalaiwi, Bahrain; Yaiguili Diversity counts 15 Alvarado García, Panama; Walid Amrane, Algeria; Hannah Aulby, Australia; Alok Basakoti, Nepal; Marisol Becerra, USA; Florencia Caminos, Argentina; Life in depth 16 Nigel Chitombo, Zimbabwe; Lisa Curtis, USA; Kate de Mattos-Shipley, UK; Linh Do, Australia; Felix Finkbeiner, Germany; Edgar Geguiento, Philippines; End of the line 17 Mirna Haidar, Lebanon; Alex Hirsch, USA; Joon Ho Yoo, Rep. -

FROM EVIDENCE to ART How Palaeoartists Bring the Ancient World to Life Volume 65 No 4 CONTENTS August/September 2018

INTERVIEW FOCUS ON NEUROSCIENCE LIZ BONNIN TALKS BIG CATS THE NEXT GENERATION THE STRANGENESS OF AND PLASTIC POLLUTION OF CANCER VACCINES ‘UNCONSCIOUS VISION’ THE MAGAZINE OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF BIOLOGY / www.rsb.org.uk ISSN 0006-3347 • Vol 65 No 4 • Aug/Sep 18 FROM EVIDENCE TO ART How palaeoartists bring the ancient world to life Volume 65 No 4 CONTENTS August/September 2018 HAVE AN IDEA FOR AN ARTICLE OR INTERESTED IN WRITING FOR US? For details contact [email protected] ROYAL SOCIETY OF BIOLOGY Charles Darwin House, 12 Roger Street, London WC1N 2JU Tel: 020 7685 2400 [email protected]; www.rsb.org.uk EDITORIAL STAFF Editor Tom Ireland MRSB @Tom_J_Ireland [email protected] ON THE COVER Chair of the Editorial Board Bringing the past to life Professor Alison Woollard FRSB 10 Palaeoartists explain how they Editorial Board reconstruct ancient worlds Dr Anthony Flemming MRSB, Syngenta Professor Adam Hart FRSB, University of Gloucestershire Dr Sarah Maddocks CBiol MRSB, Cardiff Metropolitan University UP FRONT Dr Rachael Nimmo MRSB, University College London 04 Society News Professor Shaun D Pattinson FRSB, Parliamentary Links Day; RSB Durham University chief executive honoured; Dr James Poulter MRSB, University of Leeds Biology Week 2018 Dr Cristiana P Velloso MRSB, King’s College London 06 Policy, analysis and opinion Membership enquiries The influence of scientific Tel: 01233 504804 instrument makers, and new [email protected] thinking on science investment Subscription enquiries Tel: 020 7685 2556; [email protected] The Biologist -

The Big Idea: How Business Innovators Get Great Ideas to Market

The Big Idea: How Business Innovators Get Great Ideas to Market Dearborn Trade Publishing Dedication To R. Buckminster Fuller This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative infor- mation in regard to the subject matter covered. It is sold with the under- standing that the publisher is not engaged in rendering legal, accounting, or other professional service. If legal advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional person should be sought. Acquisitions Editor: Mary B. Good Senior Managing Editor: Jack Kiburz Interior Design: Lucy Jenkins Cover Design: design literate, inc. Typesetting: Elizabeth Pitts 2002 by Steven D. Strauss Published by Dearborn Trade Publishing, a Kaplan Professional Company All rights reserved. The text of this publication, or any part thereof, may not be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permis- sion from the publisher. Printed in the United States of America 02030410987654321 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Strauss, Steven D., 1958– The big idea : how business innovators get great ideas to market / by Steven D. Strauss. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-7931-4837-5 (pbk.) 1. New products—Marketing. I. Title. HF5415.153 .S768 2002 658.5′75—dc21 2001004758 Dearborn Trade books are available at special quantity discounts to use for sales promotions, employee premiums, or educational purposes. Please call our Special Sales Department to order or for more informa- tion, at 800-621-9621, ext. 4307, or write Dearborn Trade Publishing, 155 N. Wacker Drive, Chicago, IL 60606-1719. !!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! Contents Preface vi 1. The Impossible Dream 1 Vive la France The Story of Teflon 2 Lazy Bones Jones How the Remote Control Came to Be 8 Velcro Re-creating Nature’s Velvet Crochet 14 From Radar Waves to the Radar Range The Surprise Discovery of the Microwave Oven 19 The Great Pumpkin Center Birthplace of USA Today 25 2. -

Textile Conservation Newsletter Tcn

r NUMBER 34 SPRING 1998 TCN TEXTILE CONSERVATION NEWSLETTER TCN TABLE OF CONTENTS From the Editors 3 Polish Ensis ? 4 Velcro ™ and Other Hook and Loop Fasteners: A Preliminary Study 5 of Their Stability and Ageing Characteristics Kim Izath and Mary M. Brooks Lani: Gone and Best Forgotten 12 Herbert T. Pratt Mysteries and Speculations 20 Moy Ballard Collection Condition Surveys: How We Use Them and Why 22 Shannon Elliott The Textile Conservation Centre: 1997 Final Year Projects 30 NTP Proposes Listing All Benzidine Dyes 32 Preprints ofTextile Symposium 97 Available 34 How To Reach Us Subscription Information 35 Back Issues and Supplements Available 36 Disclaimer Articles in the Textile Conservation Newsletter are not intended as complete treatments ofthe subjects butrather notes published forthe purpose of generalinterest. Affmation with the Tele Consenation Newsletter does not imply professional endorsement. 2 TCN FROM THE EDITORS It has been a difficult and unusual winter out here in Ottawa this past year. Many of us have struggled through tumultuous times because of the weather and because of continuous changes in the museum world. Museums cominue to re-organize, downsize and contract out until those of us remaining barely recognize the job we are doing. For many of us it has meant re-looking at what we are doing and what we wish to do. For myself it has measnt recognizing that I must decide in which direction to focus my energies Having survived three re-organizations in six months only to land in a job which involves neither conservation nor textiles, my involvement in the world of textile conservation has become minimal. -

Jailed for More Than Four Months, Physicist Faces Deportation Threat by Ernie Tretkoff

Inside This Issue NEWSFebruary 2004 Volume 13, No. 2 A Publication of The American Physical Society http://www.aps.org/apsnews Jailed for More Than Four Months, Physicist Faces Deportation Threat By Ernie Tretkoff In what he describes as a Kafkaesque nightmare, Branislav Djordjevic, a Serbian physicist and software engineer, recently spent over four months in jail in Virginia for an inadvertent immigration violation. Though he was released on bond in late December, he still faces possible deportation. APS leaders and its Committee on International Freedom of Scien- tists (CIFS) have written letters to immigration authorities on his be- half and continue to support his case, Free WYP Poster Inside but the outcome remains uncertain. Included in this month’s APS News is a poster advertising the Djordjevic, 48, came to the US World Year of Physics, which will take place in 2005. But it’s not from Yugoslavia in April 1991. Then early—there is good reason to display it in 2004. The whole idea of a PhD candidate in physics in the World Year of Physics is to get the word out about the impor- Belgrade, he planned to spend a se- tance and excitement of physics to the general public. And the only mester as a visiting scholar at Photo Credit: Ernie Tretkoff people who can do that are the members of the physics community, Michigan State University, working At home after his release from prison, Branislav Djordjevic holds his son Marko, who have to begin planning in 2004 if the effort is to succeed. with Michael Thorpe. -

The Inspiration Behind Hook-And-Loop (Velcro) Fastening

The inspiration behind hook-and-loop (Velcro) fastening Exploring the development of this footwear security system & its inventor’s struggle to perfect his novel product by Stuart Morgan Hook-and-loop fastening (also known as ‘touch-and-close’) has been used by footwear designers for many years. The system is commonly used where ease and speed of fastening is desirable – for instance on young children’s shoes (where the wearer has not yet mastered the skill to properly tie laces), and some items of sportswear. It has even been utilized in certain styles of fashion footwear. What is hook-and-loop? Two components are involved, typically consisting of a pair of lineal fabric strips (or shaped items) which are attached – normally by stitching or adhesive – to the opposing surfaces to be fastened. The first face features tiny hooks, and the second has even smaller loops. When the two components come into contact, the hooks catch in the loops and the two pieces bind together. When separated, by pulling or peeling the two surfaces apart, hook-and-loop strips make a distinctive ‘ripping’ sound. 1 Close-up of the hook tape of a hook-and-loop fastening The magnified view of loop tape Birth of an idea It is a common misconception that the first hook-and-loop fastening was designed by the USA’s National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) for its space program. While it is true that the organisation made good use of this product (each space shuttle reportedly flew equipped with ten thousand inches of a special fastening made of Teflon loops, polyester hooks and glass backing, used in the astronauts’ suits and to anchor equipment), the idea for hook-and-loop fastening actually dates back to the early 1940s. -

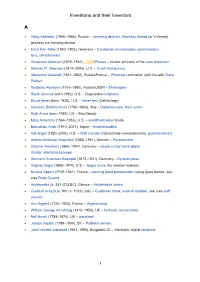

Inventions and Their Inventors A

Inventions and their Inventors A Vitaly Abalakov (1906–1986), Russia – camming devices, Abalakov thread (or V-thread) gearless ice climbing anchor Ernst Karl Abbe (1840–1905), Germany – Condenser (microscope), apochromatic lens, refractometer Hovannes Adamian (1879–1932), USSR/Russia – tricolor principle of the color television Samuel W. Alderson (1914–2005), U.S. – Crash test dummy Alexandre Alexeieff (1901–1982), Russia/France – Pinscreen animation (with his wife Claire Parker) Rostislav Alexeyev (1916–1980), Russia/USSR – Ekranoplan Randi Altschul (born 1960), U.S. – Disposable cellphone Bruce Ames (born 1928), U.S. – Ames test (Cell biology) Giovanni Battista Amici (1786–1863), Italy – Dipleidoscope, Amici prism Ruth Amos (born 1989), UK – StairSteady Mary Anderson (1866–1953), U.S. – windshield wiper blade Momofuku Ando (1910–2007), Japan – Instant noodles Hal Anger (1920–2005), U.S. – Well counter (radioactivity measurements), gamma camera Anders Knutsson Ångström (1888–1981), Sweden – Pyranometer Ottomar Anschütz (1846–1907), Germany – single-curtain focal-plane shutter, electrotachyscope Hermann Anschütz-Kaempfe (1872–1931), Germany – Gyrocompass Virginia Apgar (1909–1974), U.S. – Apgar score (for newborn babies) Nicolas Appert (1749–1841), France – canning (food preservation) using glass bottles, see also Peter Durand Archimedes (c. 287–212 BC), Greece – Archimedes' screw Guido of Arezzo (c. 991–c. 1033), Italy – Guidonian hand, musical notation, see also staff (music) Ami Argand (1750–1803), France – Argand lamp William George Armstrong (1810–1900), UK – hydraulic accumulator Neil Arnott (1788–1874), UK – waterbed Joseph Aspdin (1788–1855), UK – Portland cement John Vincent Atanasoff (1903–1995), Bulgaria/U.S. – electronic digital computer 1 Inventions and their Inventors B Charles Babbage (1791–1871), UK – Analytical engine (semi-automatic) Tabitha Babbit (1779–1853), U.S. -

Print @ Home Booklet

Print @ Home The space exploration journey comes to your home If you hold this print in your hand and the A3 colour prints are right next to you, then you are almost ready for discover the universe and also exhibition design. What you also need: ● tape ● scissors and crayons ● laptop, smartphone or computer for further research if you like Join the Step into Space missions and have fun! Get ready! To get an overview of Step into Space, you can read the text "Welcome to the space exploration trip" and "About spaceEU" in your exhibition. Then you can start with the first mission. Mission: Build your own exhibition! Take the tape and the colourful A3 prints and hang them on the wall in your living room, on a clothesline, a garden fence or any other place you think is great and could host the prints. Design your own exhibition. Oh wow, your exhibit looks great. Send us photos of your personal Step into Space exhibition to [email protected] or post them online with #stepintospace. Here are also a few examples... 1 What we made from Space You can find out here how space exploration helps us in our everyday lives. The poster "What we made from Space" in your exhibition tells you more about it. Mission: What we made from space? Look at the purple posters. There are symbols of objects like a mobile phone, sunglasses or tennis racket. How many of these objects do you have in your home? Why not bring them to your exhibition? On the following pages you can find out how these objects are connected to space science.