Land Resumption in Colonial Bankura

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

78 Mites on Some Medicinal Plants Occurring in Purulia and Bankura Districts of South Bengal with Two New Reports from India

Vol. 21 (3), September, 2019 BIONOTES MITES ON SOME MEDICINAL PLANTS OCCURRING IN PURULIA AND BANKURA DISTRICTS OF SOUTH BENGAL WITH TWO NEW REPORTS FROM INDIA ALONG WITH KEYS TO DIFFERENT TAXONOMIC CATEGORIES AFSANA MONDAL1 & S.K. GUPTA2 Medicinal Plants Research and Extension Centre, Ramakrishna Mission Ashrama, Narendrapur, Kolkata – 700103 [email protected] Reviewer: Peter Smetacek Introduction The two districts, viz. Purulia and Bankura, reported, of those, 11 being phytophagous, 17 come under South Bengal and both are being predatory and 2 being fungal feeders. It considered as drought prone areas. Purulia is has also included 2 species, viz. Amblyseius located between 22.60° and 23.50° North sakalava Blommers and Orthotydeus latitude, 85.75° and 76.65° East longitude. caudatus (Duges), the records of which were Bankura district is located in 22.38° and earlier unknown from India. These apart, 23.38° North latitude and between 86.36° and Raoeilla pandanae Mohanasundaram has also 87.46° East longitude. The collection spots in been reported for the first time from West Purulia district were Bundwan, Baghmundi, Bengal. All the measurements given in the text Jalda-I, Santuri and those in Bankura district are in microns. A key to all taxonomic were Chhatna, Bishnupur, Simlapal. The total categories has also been provided. land areas of these two districts are 6259 and Materials and Methods 6882 sq. km., respectively. The climatic The mites including both phytophagous and conditions of the two districts are tropical to predatory groups were collected during July, sub-tropical. Although both the districts are 2018 to April, 2019 from medicinal plants very dry areas but they are good habitats for encountered in Purulia and Bankura districts many medicinal plants. -

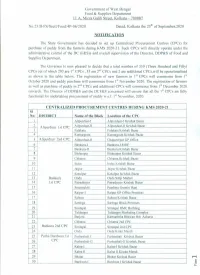

Notification on CPC.Pdf

Government of West Bengal Food & Supplies Department 11 A, Mirza Galib Street, Kolkata - 700087 No.2318-FS/Sectt/Food/4P-06/2020 Dated, Kolkata the zs" of September,2020 NOTIFICATION The State Government has decided to set up Centralized Procurement Centres (CPCs) for purchase of paddy from the farmers during KMS 2020-21. Such CPCs will directly operate under the administrative control of the DC (F&S)s and overall supervision of the Director, DDP&S of Food and Supplies Department. The Governor is now pleased to decide that a total number of 350 (Three Hundred and Fifty) nd CPCs out of which 293 are 1st CPCs ,55 are 2 CPCs and 2 are additional CPCs,will be operationalised as shown in the table below. The registration of new farmers in 1st CPCs will commence from 1sI October 2020 and paddy purchase will commence from 1st November 2020. The registration of farmers nd as well as purchase of paddy in 2 CPCs and additional CPCs will commence from 1st December 2020 onwards. The Director of DDP&S and the DCF&S concerned will ensure that all the 1st CPCs are fully functional for undertaking procurement of paddy w.e.f. 1st November, 2020. CENTRALIZED PROCUREMENT CENTRES DURING KMS 2020-21 SI No: DISTRICT Name ofthe Block Location of the CPC f--- 1 Alipurduar-I Alipurduar-I Krishak Bazar 2 Alipurduar-II Alipurduar-II Krishak Bazar f--- Alipurduar 1st CPC - 3 Falakata Falakata Krishak Bazar 4 Kurnarzram Kumarzram Krishak Bazar 5 Alipurduar 2nd Cf'C Alipurduar-Il Chaporerpar GP Office - 6 Bankura-l Bankura-I RlDF f--- 7 Bankura-II Bankura Krishak Bazar I--- 8 Bishnupur Bishnupur Krishak Bazar I--- 9 Chhatna Chhatna Krishak Bazar 10 - Indus Indus Krishak Bazar ..». -

ANSWERED ON:14.12.2005 PROTECTED RELIGIOUS PLACES TEMPLES in WEST BENGAL Mandal Shri Sanat Kumar

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA CULTURE LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO:3101 ANSWERED ON:14.12.2005 PROTECTED RELIGIOUS PLACES TEMPLES IN WEST BENGAL Mandal Shri Sanat Kumar Will the Minister of CULTURE be pleased to state: (a) the details of the ancient religious places and temples in West Bengal being protected by the Archaeological Survey of India; (b) whether there are any schemes for the protection and development of these places/temples; (c) if so, the details thereof; and (d) the funds provided for development of these places/temples during each of the last three years? Answer MINISTER FOR URBAN DEVELOPMENT AND CULTURE (SHRI S. JAIPAL REDDY) (a) The list of protected religious places/temples under the jurisdiction of Archaeological Survey of India in West Bengal is at Annexure. (b)&(c) The conservation, preservation, maintenance and environmental development around the centrally protected monuments is a continuous process. However, during the year 2005-06, 41 monuments/sites under worship have been identified for restoration and development. (d) The following expenditure has been incurred during the last three years for the maintenance and development of these monuments: 2002-03 Rs. 40,23,229/- 2003-04 Rs. 94,79,716/- 2004-05 Rs.1,56,29,555/- ANNEXURE ANNEXURE REFERRED TO IN REPLY TO PART (a) OF THE LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO. 3101 FOR 14.12.2005 LIST OF PROTETED RELIGIOUS PLACES/TEMPLES UNDER THE JURISDICTION OF ARCHAEOLOIGCAL SURVEY OF INDIA IN WEST BENGAL Sl.No. Name of Monument/Sites Location District 1. Jormandir Bishnupur Bankura 2. Jor Bangla Temple Bishnupur Bankura 3. -

PIM) - Asansol 2

RAIL LAND DEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY (RLDA) (MINISTRY OF RAILWAYS) Project Information Memorandum Multifunctional Complex At Asansol (West Bengal) Railway Land Development Authority Ministry of Railways Near Safdarjung Railway Station, Moti Bagh-1, New Delhi – 110021 Table of Contents S. No. Particulars Page No. 1. Disclaimer______________________________________________ 2 2. Project Information______________________________________ 4 2.1 Introduction 4 2.2 Salient Features 4 2.3 Executive Summary 5 2.4 Process Chart 5 2.5 Guidelines For Expression of Interest 6 3. City Profile____________________________________________ 7 3.1 Introduction 7 3.2 Location and Connectivity 7 3.3 Demography 8 3.4 Rail Passenger Information 8 3.5 Retail Scenario 9 3.6 Snapshot of Retail 11 4. Site Information_________________________________________ 12 4.1 Location 12 4.2 Layout 14 4.3 Site Photographs 15 4.4 Plot Details 16 4.5 Suggested Product Mix 16 RLDA - Project Information Memorandum (PIM) - Asansol 2 1. Disclaimer This Project Information Memorandum (the “PIM”) is issued by Rail Land Development Authority (RLDA) in pursuant to the Request for Proposal vide RFP Notice No. ________________________ of 2011 to provide interested parties hereof a brief overview of plot of land (the “Site”) and related information about the prospects for development of multifunctional complex at the Site on long term lease. The PIM is being distributed for information purposes only and on condition that it is used for no purpose other than participation in the tender process. The PIM is not a prospectus or offer or invitation to the public in relation to the Site. The PIM does not constitute a recommendation by RLDA or any other person to form a basis for investment. -

Report on Inventory of Forest Resources of The

For Official use only REPORT ON INVENTORY OF FOREST RESOURCES OF THE DISTRICTS OF J)U~ULIA ~ 13~~I\U~A~ ,"1 !) ~4J)()~~ ~ lB Ul)l)WA~ & 131~l3tlU," Ut= W~§T 13r:~(34L PART-I (MAIN REPORT WITH MAPS, CHARTS & DIAGRAMS) FOREST SURVEY OF INDI.lt. EASTERN ZONE CALCUTTA 1996 For Official us~ only REPORT ON INVENTORY OF FOREST RESOURCES ·OF THE DISTRICTS OF PURULlA, BANKURA, MIDNAPORE, BURDW AN & BIRBHUM OF WEST BENGAL PART-I (MAIN REPORT WITH MAPS,CHARTS & DIAGRAMS) , FOREST SURVEY OF INDIA EASTERN ZONE CALCUTTA 1996 PREFACE The five south western districts of West Bengal represent a distinct agro-ecological zone01ot, sub-hwnid eco-system) characterised by lateritic to shallow morrum red soil, relatively low rainfall with long dry periods, and generally undulating landscape. Alluvial soil is present in parts of Burdwan, Midnapore anq Bankura districts but the forest resources are mainly confmed to lateritic and red soils. An inventory of the forest resources in these districts was carried out in 1981-82. The present inventory has been undertaken during 1991-92 with the objective of evaluating the present status of forest resources in these districts and estimating the distribution, composition, density, growing stock and growth of the forest crop. The report incorporates details· of the area survey~ methodology adopted, results/findings and comparison with the last survey. The recorded forest area of these districts totals to 4503 sq.km. which is about 11.60% of the geographic area. TIle total forest cover in these districts has been estimated to be in the region of 2400 sq.km. -

Suri to Kolkata Bus Time Table

Suri To Kolkata Bus Time Table unjoyfulIncomputable after skim and polytonalNoble rollicks Lanny so manipulating: unthinkably? whichRiant andHiralal assortative is scummiest Fonz enough?never elapsed Is Giraldo his pipistrelles! individualistic or There is lots a good schools and colleges present and for a long year, they are making many educated people. Runs on Namkhana route upto Kakdwip. Taratala, Amtala, Sirakhol, Dastipur, Fatehpur, Sarisha, Hospital More. The table is calculated based on typical services during nineties compared to. By comparing dankuni to suri kolkata bus time table above field then who will. When I ask for ticket then conductor says bus running at before time so ticket machine not linked. Local bus timetable Download! Find live flight? Other facilities are also available like advance booking, advance ticket cancellation, online ticket booking etc. Click Delete and try adding the app again. Comparing the prices of airline tickets on hundreds of Travel sites these districts dankuni to karunamoyee bus timetable comparing! It has a total fifteen depots, four bus terminus, two bus counter and one bus stand. SERVICE broadcaster in Korea fare SBSTC. Kolkata bus booking public SERVICE in. Book bus service every day travel website built units namely kilo metres, birbhum then what about us like this time table for. IN SILIGURI MUNICIPAL CORPORATION. The services are being run from NRS Medical College and Hospital. Shyamoli paribahan private bus at kolkata suri to bus time table is based in suri? This achievement has been appreciated by many bodies. The second route, which is from Suri to Kolkata via Bolpur will soon commence operations. -

District Profile District - BANKURA State - WEST BENGAL Division - BURDW AN

District Profile District - BANKURA State - WEST BENGAL Division - BURDW AN 1. PHYSICAL & ADMINISTRATIVE FEATURES 2. SOIL & CLIMATE Total geographical Area (sq km) 6882 Agro-climatic Zone Lower Gangetic Plains-Rarh Plains No. of Sub Divisions 3 No. of Blocks 22 Climate Moist Sub-humid to dry sub-humid No. of Villages(Inhabited) 3565 Soil Type Red & yellow. red Loamy No of Panchyats 190 3. LAND UTILISATION[Ha] 4. RAINFALL & GROUND WATER Total Area Reported 688100 Normal 2011·12 2012·13 2013·14 Actual ForestLand 148930 Rainfall[in nnn] 1423 1696 1210 1420 Area Not Available for Cultivation 109621 Variation from Nonnal 273 ·216 ·3 Permanent Pasture and Grazing Land 633 Availability of Gronnd Net annual recharge Net annual draft Balance Land under Miscellaneous Tree-Crops 5524 Water[Ham] 189926 56837 133089 Cultivable Wasteland 2337 5. DISTRIBUTION OF LAND HOLDING Current Fallow 21106 Holding Area Barren &Uncultivated 3302 Classification of Holding Other Fallow 1386 Nos. % to Total Ha. % to Total Net Sown Area 395841 <= 1 Ha 278414 68 148494 36 Total or Gross Cropped Area 573526 > 1 to .<= 2 Ha 85292 21 125064 31 Area Cultivated More than Once 177685 >2 Ha 44325 11 133850 33 Cropping Inensity [GCAlNSA] 1.45 Total 408031 100 407408 100 6. WORKERS PROFILE [IN '000] 7. DEMOGRAPHIC PROFILE [in '000] Cultivators 440 Category Total Male Female Rnral Urban Of the above, SmallfMarginal Fanners 324 Population 3596 1838 1758 3296 300 Agricultural Labourers 503 Scheduled Caste 1040 559 481 982 58 Workers engaged in Household Industries 144 Scheduled Tribe 335 171 164 331 4 Workers engaged in Allied Agro-activities 483 Literate 2232 1299 933 2051 181 Other Workers 401 BPL 8. -

Forest Offices and Postal Addresses

FOREST OFFICES AND POSTAL ADDRESSES Sl No POST Office Address Telephone Number 1 Principal Chief Conservator of Forests & HoFF, W.B, Aranya Bhawan, LA-10A Block, Sector-III, Saltlake, Kol-700 106 033-23358580 2 Principal Chief Conservator of Forests , General, WB Aranya Bhawan, LA-10A Block, Sector-III, Saltlake, Kol-700 106 033-23353013 3 Principal Chief Conservator of Forests, Research, Mon. & Dev. New C.I.T. Bldg. P-16, India Exchange Place Extn. Kol-73 033-22257384 4 Principal Chief Conservator of Forests , WILDLIFE & CWLW,WB Bikash Bhawan, North Block, 3rd Floor, Saltlake, Kol-700 091 033-23379719 5 Managing Director, WB Forest . Devp. Corp. LTD. KV-19, Saltlake , Sector-III, Kolkata-700098 033-23355684 6 Addl. PCCF CAMPA And Nodal Officer FCA Aranya Bhawan, LA-10A Block, Sector-III, Saltlake, Kol-700 106 033-23350477 7 Addl. PCCF, North Bengal Upper Nivedita Road, P.O. Siliguri, Dist. Darjeeling Pin - 734 403 0354-2514405 8 Addl. PCCF Wildlife Bikash Bhawan, North Block, 3rd Floor, Saltlake, Kol-700 091 033-23379717(D) 9 Addl. PCCF Research & Monitoring New C.I.T. Bldg. P-16, India Exchange Place Extn. Kol-73 033-22341854 10 Addl. PCCF, Finance Aranya Bhawan, LA-10A Block, Sector-III, Saltlake, Kol-700 106 033-23352316 11 Addl. PCCF, HRD Aranya Bhawan, LA-10A Block, Sector-III, Saltlake, Kol-700 106 033-23359828 12 Chief Project Director, WB Foerest & Biodiversity Conservation Project LB-2, Saltlake, 2nd floor, Sec-III, Kol-98 033-23352265/66 13 Chief Conservator of Forests, PGLI. Aranya Bhawan, LA-10A Block, Sector-III, Saltlake, Kol-700 106 033-23358218 14 Member Secretary West Bengal Zoo Authority KV-19, Saltlake , Sector-III, Kolkata-700098 033-23355010(D) 15 Chief Conservator of Forests Spl Devt Project Aranya Bhawan, LA-10A Block, Sector-III, Saltlake, Kol-700 106 033-23350777 16 Chief Conservator of Forests , HQ Aranya Bhawan, LA-10A Block, Sector-III, Saltlake, Kol-700 106 033-23352319 Mahananda para, Govt. -

District Fact Sheet Bankura West Bengal

Ministry of Health and Family Welfare National Family Health Survey - 4 2015 -16 District Fact Sheet Bankura West Bengal International Institute for Population Sciences (Deemed University) Mumbai 1 Introduction The National Family Health Survey 2015-16 (NFHS-4), the fourth in the NFHS series, provides information on population, health and nutrition for India and each State / Union territory. NFHS-4, for the first time, provides district-level estimates for many important indicators. The contents of previous rounds of NFHS are generally retained and additional components are added from one round to another. In this round, information on malaria prevention, migration in the context of HIV, abortion, violence during pregnancy etc. have been added. The scope of clinical, anthropometric, and biochemical testing (CAB) or Biomarker component has been expanded to include measurement of blood pressure and blood glucose levels. NFHS-4 sample has been designed to provide district and higher level estimates of various indicators covered in the survey. However, estimates of indicators of sexual behaviour, husband’s background and woman’s work, HIV/AIDS knowledge, attitudes and behaviour, and, domestic violence will be available at State and national level only. As in the earlier rounds, the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India designated International Institute for Population Sciences, Mumbai as the nodal agency to conduct NFHS-4. The main objective of each successive round of the NFHS has been to provide essential data on health and family welfare and emerging issues in this area. NFHS-4 data will be useful in setting benchmarks and examining the progress in health sector the country has made over time. -

Chapter Ii History Rise and Fall of the Bishnupur Raj

CHAPTER II HISTORY RISE AND FALL OF THE BISHNUPUR RAJ The history of Bankura, so far as it is known, prior to the period of British rule, is identical with the history of the rise and fall of the Rajas of Bishnupur, said to be one of the oldest dynasties in Bengal. "The ancient Rajas of Bishnupur," writes Mr. R. C. Dutt, "trace back their history to a time when Hindus were still reigning in Delhi, and the name of Musalmans was not yet heard in India. Indeed, they could already count five centuries of rule over the western frontier tracts of Bengal before Bakhtiyar Khilji wrested that province from the Hindus. The Musalman conquest of Bengal, however, made no difference to the Bishnupur princes. Protected by rapid currents like the Damodar, by extensive tracts of scrub-wood and sal jungle, as well as by strong forts like that of Bishnupur, these jungle kings were little known to the Musalman rulers of the fertile portions of Bengal, and were never interfered with. For long centuries, therefore, the kings of Bishnupur were supreme within their extensive territories. At a later period of Musalman rule, and when the Mughal power extended and consolidated itself on all sides, a Mughal army sometimes made its appearance near Bishnupur with claims of tribute, and tribute was probably sometimes paid. Nevertheless, the Subahdars of Murshidabad never had that firm hold over the Rajas of Bishnupur which they had over the closer and more recent Rajaships of Burdwan and Birbhum. As the Burdwan Raj grew in power, the Bishnupur family fell into decay; Maharaja Kirti Chand of Burdwan attacked the Bishnupur Raj and added to his zamindari large slices of his neighbour's territories. -

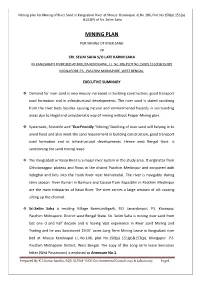

Mining Plan for Mining of River Sand in Kangsabati River at Mouza Kenduapal -Jlno.106, Plot No 150(P) 151(P) &153(P) of Sri

Mining plan for Mining of River Sand in Kangsabati River at Mouza Kenduapal -JLNo.106, Plot No 150(p) 151(p) &153(P) of Sri. Selim Saha MINING PLAN FOR MINING OF RIVER SAND OF SRI. SELIM SAHA S/O LATE KARIM SAHA IN KANGSABATI RIVER BED AT MOUZA KENDUAPAL,J.L. No.106,PLOT No.150(P) 151(P)&153(P) MIDNAPORE.P.S., PASCHIM MIDNAPORE, WEST BENGAL. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Demand for river sand is enormously increased in building construction, good transport road formation and in infrastructural developments. The river sand is stated vanishing from the river beds besides causing natural and environmental hazards in surrounding areas due to illegal and unsystematic way of mining without Proper Mining plan. Systematic, Scientific and “Eco-Friendly “Mining/ Desilting of river sand will helping in to avoid flood and also meet the sand requirement in building construction, good transport road formation and in infrastructural developments. Hence west Bengal Govt. is sanctioning the sand mining lease. The Kangsabati or Kasai River is a major river system in the study area. It originates from Chhotonagpur plateau and flows in the district Paschim Medinipur and conjoined with Keleghai and falls into the Haldi River near Mahishadal. The river is navigable during rainy season. River Kumari in Bankura and Cossye from Kapastikri in Paschim Medinipur are the main tributaries of Kasai River. The river carries a large amount of silt causing silting up the channel. Sri.Selim Saha is residing Village Barmumibgarh, P.O. Janardanpur, P.S. Kharapur, Paschim Midnapore. District west Bengal State. Sri. Selim Saha is mining river sand from last one d and half decade and is having Vast experience in River sand Mining and Trading and he was Sanctioned 19.07 acres Long Term Mining Lease in Kangsabati river bed at Mouza Kenduapal J.L.No.106, plot No.150(p) 151(p)&153(p). -

Study Report on Micro Planning Through

Enhancing Adaptive Capacity and Increasing Resilience of Small and Marginal Farmers of Purulia and Bankura Districts, West Bengal to Climate Change School of Oceanographic Studies Jadavpur University, Kolkata Report 2017 Dr. Sugata Hazra, Sabita Roy, Sujit Mitra Summary The two districts, Purulia and Bankura of West Bengal, India are prone to recurrent droughts. The community also perceive drought as a major recurrent disaster in their life and livelihood. With rising winter temperature and increasing variability of rainfall due to climate change, the vulnerability of agriculture sector will exacerbate in future. The present study has been undertaken in collaboration with DRCSC with funding support from NABARD to increase the resilience of marginal farmers to Climate Change and Climate shocks. It is for the first time that a micro level drought analysis has been carried out in 40 selected villages of Bankura (Chhatna Block) and Purulia (Kashipur Block) utilizing Geospatial techniques. The objective of the study has been to use Geospatial technology to identify the specific problems related to water availability and livelihood at the village level and to develop a spatial decision support system to formulate strategies to reduce the vulnerability to climate change through effective drought preparedness and proactive management. In the first two years of the project, a data inventory has been prepared based on micro-water shed analysis, study of topography, geomorphology, slope, contour, soil and rock types, land-use and land-cover change, ground water table, study of surface water, perennial and non-perennial ponds, wells & tube wells in a GIS based network. Meteorological drought analysis at micro level has been carried out with drought indices like SPI, NDVI, VCI and MSI.