Havasupai Relations with Washington

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trip Planner

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Grand Canyon National Park Grand Canyon, Arizona Trip Planner Table of Contents WELCOME TO GRAND CANYON ................... 2 GENERAL INFORMATION ............................... 3 GETTING TO GRAND CANYON ...................... 4 WEATHER ........................................................ 5 SOUTH RIM ..................................................... 6 SOUTH RIM SERVICES AND FACILITIES ......... 7 NORTH RIM ..................................................... 8 NORTH RIM SERVICES AND FACILITIES ......... 9 TOURS AND TRIPS .......................................... 10 HIKING MAP ................................................... 12 DAY HIKING .................................................... 13 HIKING TIPS .................................................... 14 BACKPACKING ................................................ 15 GET INVOLVED ................................................ 17 OUTSIDE THE NATIONAL PARK ..................... 18 PARK PARTNERS ............................................. 19 Navigating Trip Planner This document uses links to ease navigation. A box around a word or website indicates a link. Welcome to Grand Canyon Welcome to Grand Canyon National Park! For many, a visit to Grand Canyon is a once in a lifetime opportunity and we hope you find the following pages useful for trip planning. Whether your first visit or your tenth, this planner can help you design the trip of your dreams. As we welcome over 6 million visitors a year to Grand Canyon, your -

Communities on Indian Reservations in Arizona

APPENDIX A TRIBAL COMMUNITIES OF AMERICAN INDIANS IN ARIZONA TRIBAL COMMUNITIES OF AMERICAN INDIANS IN ARIZONA Reservation/Tribe County Community name AK-CHIN INDIAN COMMUNITY Pinal Ak Chin Maricopa COCOPAH TRIBE Yuma Cocopah Reservation COLORADO RIVER INDIAN TRIBE La Paz Parker Parker Valley Poston FORT MCDOWELL YAVAPAI NATION Maricopa Fort McDowell FORT MOJAVE INDIAN TRIBE Mohave Fort Mojave Reservation FORT YUMA-QUECHAN TRIBE Yuma Fort Yuma Reservation GILA RIVER INDIAN COMMUNITY Maricopa Chandler Heights Firebird Lake Gila Crossing Komatke Lone Butte Maricopa Village St. Johns Pinal Bapchule Blackwater Casa Blanca Coclkleburr Goodyear Lower Santan Maricopa North Blackwater Olberg Progressive Colony Sacate Sacaton Sacaton Flats Santa Cruz Snaketown South Casa Blanca South Goodyear Stotonic Sweetwater Upper Santan West Casa Blanca West Chandler Wetcamp TRIBAL COMMUNITIES OF AMERICAN INDIANS IN ARIZONA (continued) Reservation/Tribe County Community name HAVASUPAI NATION Coconino Supai HOPI TRIBE Coconino Coal Mine Mesa Moenave Moenkopi Sand Springs Navajo Bacobi Dennebito Five House Hano Hotevilla Keams Canyon Kykotsmovi Mishongnovi Old Oraibi Polacca Second Mesa Shipaulovi Shungopovi Sichomovi Toreva Wali Polacca Walpi Wepo Village HUALAPAI NATION Coconino Fraziers Well Mohave Hindu Canyon Peach Springs Valentine KAIBAB-PAIUTE TRIBE Mohave Juniper Estates Kaibab Moccasin Redhills Six Mile Steam Boat NAVAJO NATION Apache Allentown Black Mountain Blue Canyon Blue Gap Chinle Cornfields Cottonwood TRIBAL COMMUNITIES OF AMERICAN INDIANS -

Speaker Morgan, 21St Navajo Nation Council Recognizes Havasupai Tribe’S Efforts in Protecting Dook’O’Slííd During 2010 Fall Session

The Navajo Nation Council — Office of the Speaker Contact: Laphillda Tso, Public Information Officer Phone: (928) 871-6813 Cell: (928) 255-2942 Fax: (928) 871-7255 [email protected] October 26, 2010 [email protected] FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE www.navajonationcouncil.org Speaker Morgan, 21st Navajo Nation Council recognizes Havasupai Tribe’s efforts in protecting Dook’o’slííd during 2010 Fall Session WINDOW ROCK, Ariz. — During its 2010 Fall Session, Speaker Lawrence T. Morgan and the 21st Navajo Nation Council presented representatives from the Havasupai Tribe with gifts of appreciation because the Havasupai Tribe, other tribes and the Navajo Nation formed a united tribal front to oppose snowmaking on Dook’o’slííd. Thomas Walker Jr. (Birdsprings/Leupp/Tolani Lake), who advocated for the Navajo Nation, presented gifts to Edmund Tilousi, Vice Chair of the Havasupai Tribe, Carletta Tilousi, councilwoman for the Havasupai Tribe and Hertha Woody, Sierra Club volunteer, of Shiprock, N.M. Left to right: Eric Descheenie, Legislative Staff Assistant; Thomas Walker, Council Delegate (Birdsprings/Leupp/Tolani Lake); Carletta Tilousi, Havasupai Tribe Councilwoman: Hertha Woody, Sierra Club Volunteer. Absent is Edmund Tilousi, Havasupai Tribe Vice Chair. (Photo by Speaker Morgan and the 21st Navajo Nation Laphillda Tso) Council are grateful for the relationship that has been built with the Havasupai Tribe. The Havasupai’s involvement in helping form a united tribal front, along with the Navajo Nation, protects the sanctity of the San Francisco Peaks -- Dook’o’oslííd, which ultimately made a significant difference in the Flagstaff City Council’s decision to disapprove the substitute water sale agreement to make artificial snow at the Arizona Snowbowl. -

Havasupai Nation Field Trip May 16 – 20, 2012 by Melissa Armstrong

Havasupai Nation Field Trip May 16 – 20, 2012 By Melissa Armstrong The ESA SEEDS program had a field trip to Flagstaff, AZ the Havasupai Nation in Western Grand Canyon from May 16 – 20, 2012 as part of the Western Sustainable Communities project with funding from the David and Lucille Packard Foundation. The focus of the field trip was on water sustainability of the Colorado River Basin from a cultural and ecological perspective. The idea for this field trip arose during the Western Regional Leadership Meeting held in Flagstaff in April 2011 as a way to ground our meeting discussions in one of the most iconic places of the Colorado Plateau – the Grand Canyon. SEEDS alumnus Hertha Woody helped ESA connect with the Havasupai Nation; she worked closely with the former Havasupai tribal council during her tenure with Grand Canyon Trust as a tribal liaison. Hertha was instrumental in the planning of this experience for students. In attendance for this field trip were 17 undergraduate and graduate students, 1 alumnus, 1 Chapter advisor, and 2 ESA staff members (21 people total), representing eight Chapter campuses (Dine College Tuba City and Shiprock campuses, ASU, NAU, UNM, SIPI, NMSU, Stanford) – See Appendix A. The students were from a diverse and vibrant background; 42% were Native American, 26% White, 26% Hispanic and 5% Asian. All four of our speakers were Native American. The overall experience was profound given the esteem and generosity of the people who shared their knowledge with our group, the scale of the issues that were raised, the incredibly beautiful setting of Havasu Canyon, and the significant effort that it took to hike to Supai Village and the campgrounds – approximately 30 miles in three days at an elevation change of 1,500 feet each way. -

US House of Representatives Natural Resources Subcommittee

US House of Representatives Natural Resources Subcommittee Havasupai Tribe – Support for HR 1373 and Permanent Protection of the Grand Canyon Watershed from Mining Introduction My name is Carletta Tilousi and I am an elected Member of the Havasupai Tribal Council. I am here on behalf of the Havasupai Tribe to support HR 1373, which will permanently ban uranium mining and the establishment of new mining claims on federal lands located next to the Grand Canyon National Park and the Havasupai Indian Reservation. The Tribe supports the Bill because it will permanently protect one million acres of public lands from mining, including uranium mining that threatens Havasu Creek, which flows through our homeland and forms our famous waterfalls. The Grand Canyon is a world famous natural wonder and a national treasure. Millions of people visit the Grand Canyon every year. Many Americans falsely believe that public lands like the Grand Canyon, and the federal lands surrounding the Grand Canyon, are already protected from development and mining. However, the 1872 Mining Law, that is still a valid US law, allows mining companies to stake mining claims and conduct mining operations on public lands. 1 Uranium mining has already poisoned and will continue to poison the Grand Canyon. It will poison the groundwater and aquifers that feed into the Colorado River. It will poison the land, the plants, the animals, the people that live there, and the visitors. The Havasupai Tribe is one of the most remote communities in North America. We are located at the bottom of the Grand Canyon in Supai Village, which is accessible only by horse, helicopter, or 8-mile hike. -

Havasupai Trip Itinerary

Havasupai Trip Itinerary Trip Information School Shorecrest Preparatory School Dates June 4th, 2015 - June 10th, 2015 Lead Teacher Steve Collins Travelers 12 total, 11 students, 1 adults Emergency # (866) 211-7399 Tour Guide(s) Alyssa Kinnier, Amanda Sahli Flight Information Record Locator Carrier United Airlines #s Flight Airports Depart Arrive United Airlines 1536 Tampa, FL (TPA) 6:47 AM 7:55 AM - Houston, TX (IAH) Outbound United Airlines 1635 Houston, TX 9:00 AM 10:16 AM (IAH) - Las Vegas, NV (LAS) United Airlines 1981 Las Vegas, NV 12:32 AM 5:31 AM (LAS) - Houston, TX (IAH) Return United Airlines 1227 Houston, TX 7:22 AM 10:36 AM (IAH) - Tampa, FL (TPA) Hotel Information Date Hotel Phone # Address Jun 04 - Jun 05 Best Western King's Inn Kingman (928) 753-6101 2930 E Andy Devine Ave, Kingman, AZ 86401 Jun 07 - Jun 08 Springhill Suites Flagstaff (928) 774-8042 2455 S Beulah Blvd, Flagstaff, AZ 86001 Jun 08 - Jun 09 Holiday Inn Express Lake Powell (928) 645-9900 643 South Lake Powell Blvd, Page, AZ 86040 Jun 09 - Jun 10 Hampton Inn--Springdale/Zion (435) 627-9191 1127 Zion Park Boulevard, Springdale, UT 84767 Trip Itinerary Thursday, June 4 Friday, June 5 Saturday, June 6 Sunday, June 7 6:47 AM - 7:55 AM Flight 6:00 AM Hotel breakfast Breakfast at camp Early breakfast and prepare from Tampa, FL to Houston, 6:30 AM Depart for Break into groups of 5-7 for hike out of canyon TX Havasupai trailhead people per guide to explore Depart for ten mile hike out of 9:00 AM - 10:16 AM Flight Best Western Kings Inn - the Canyon canyon from Houston, -

An Adm I N I Strati Ve History of Grand Ca Nyon Nati Onal Pa R K Becomingchapter a Natio Onenal Park -

Figure 1.Map ofGrand Canyon National Monument/Grand Canyon Game Preserve, National Game Preserve (created by Roosevelt in 1906),and unassigned public domain. ca.1906-10. President Theodore Roosevelt liberally interpreted the 1906 Antiquities Act The U.S.Forest Service managed the monument from 1908 until it became a national when he established by proclamation the 1,279-square-milerand G Canyon National park in 1919, relying entirely on the Santa Fe Railroad to invest in roads,trails,and Monument in 1908.The monument was carved from Grand Canyon National Forest amenities to accommodate a budding tourism industry. (created by President Benjamin Harrison as a forest reserve in 1893), Grand Canyon an adm i n i strati ve history of grand ca nyon nati onal pa r k BecomingChapter a Natio Onenal Park - In the decades after the Mexican-American War, federal explorers and military in the Southwest located transportation routes, identified natural resources, and brushed aside resistant Indian peo p l e s . It was during this time that Europ ean America n s , fo ll o wing new east-west wagon roads, approached the rim of the Grand Canyon.1 The Atlantic & Pacific Railroad’s arrival in the Southwest accelerated this settlement, opening the region to entrepreneurs who initially invested in traditional economic ventures.Capitalists would have a difficult time figuring out how to profitably exploit the canyon,how- ever, biding their time until pioneers had pointed the way to a promising export economy: tourism. Beginning in the late 1890s, conflicts erupted between individualists who had launched this nascent industry and corporations who glimpsed its potential. -

A Confluence of Anticolonial Pathways for Indigenous Sacred Site Protection *Rachel Ellis1 and Denielle Perry2

88 Universities Council on Water Resources Journal of Contemporary Water Research & Education Issue 169, Pages 8-26, April 2020 A Confluence of Anticolonial Pathways for Indigenous Sacred Site Protection *Rachel Ellis1 and Denielle Perry2 1Sustainable Communities, Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, AZ 2School of Earth and Sustainability, Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, AZ *Corresponding Author Abstract: The confluence of the Little Colorado and Colorado Rivers is an Indigenous socio-ecological landscape, revolving in large part around water resources. Substantial surface and groundwater use within the Little Colorado River (LCR) basin threatens the water sources of the confluence, springs in the LCR basin, and specifically the Hopi Sipapuni—a sacred site of cultural emergence. To address concerns about diminished flows of sacred springs, we engaged in praxis through collaborative, reciprocal, community- based research processes. Through the lens of anticolonial theory, we ask: Can federal policies be employed in an anticolonial pursuit of water and sacred site protection? How do Indigenous grassroots organizers envision protection and work to re-Indigenize water management? Semi-structured interviews with Indigenous community organizers and federal land managers were coupled with policy analysis of the National Historic Preservation Act/Traditional Cultural Properties, the ongoing LCR Adjudication, and the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. Findings point to multifaceted, complex, and contradictory themes that elucidate the continued influence of colonization on water governance and the degree to which protection solutions can be anticolonial. Criteria were generated for anticolonial protective pathways that highlight the centrality of reciprocal relationships, Indigenous Knowledges, and meaningful inclusion. While details about protection pathways for the confluence and Sipapuni are many, the salient finding is that the struggle for water protection in the LCR is the struggle for protection of inherent Indigenous rights. -

Havasupai Tribe, Genetic Research, Informed Consent

1 Also known as the People of the Blue Green water. The tribe lives in Supai, AZ, which is over 1,000 years old. It is a remote village that is located eight miles below the rim of the Grand Canyon. You must hike in to get to the village. A hidden limestone aquifer provides the blue green waters that nourish fields of corn, squash and beans for the tribe in the harsh desert landscape which supported the tribes way of life. In 1882, the US Government declared the tribe's Grand Canyon land to be a national park. The Havasupai were confined to a small area at the bottom of the canyon. After a long 100 years, the US Government finally restored 185,000 acres back to the tribe. By that time traditional hunting, fishing, and farming had already been replaced by tourism. Along with the tourists and visitors came new non-native food and drinks. The Havasupai were ravaged by type 2 diabetes. 2 A brief history of the Havasupai as told by a tribal member. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WcIkah78LMQ 3 AIs (American Indians) were forcibly removed from their homelands by governmental authorities and resettled in areas unfamiliar to them. Native languages and religious practices were banned. In 1882, Courts of Indian Offenses “discouraged” “heathenish” AI cultural practices, including certain dances, rituals, and use of traditional healers. In the Late 1800s to early 1900s, AI children were forcibly removed from their families and sent to federal Indian boarding schools that were designed explicitly to extinguish Indian cultures. -

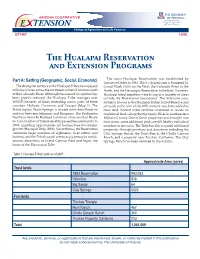

The Hualapai Reservation and Extension Programs

ARIZONA COOPERATIVE E TENSION College of Agriculture and Life Sciences AZ1467 10/08 The Hualapai Reservation and Extension Programs Part A: Setting (Geographic, Social, Economic) The main Hualapai Reservation was established by Executive Order in 1883. This U-shaped area is bordered by The aboriginal territory of the Hualapai Tribe encompassed Grand Wash Cliffs on the West, the Colorado River to the millions of acres across the northwest corner of Arizona south North, and the Havasupai Reservation to the East. However, of the Colorado River. Although this area of occupation has Hualapai tribal members were living in a number of areas been greatly reduced, the Hualapai Tribe manages over outside the Reservation boundaries. The Valentine area, 400,000 hectares of lands extending across parts of three formerly known as the Hualapai Indian School Reserve and counties: Mohave, Coconino, and Yavapai (Map 1). The set aside at the turn of the 20th century, was later added as Tribal capital, Peach Springs, is located on historic Route 66 trust land. Several tribal families continued to reside on midway between Seligman and Kingman. The Burlington traditional lands along the Big Sandy River in southeastern Northern Santa Fe Railroad travels on a line south of Route Mohave County. One of these properties was brought into 66. Construction of Interstate 40 bypassed the community in trust status, some additional lands are still held by individual 1978, impeding opportunities for tourism-based economic members in fee status. The Tribe has also acquired additional growth (Hualapai Tribe, 2006). Nevertheless, the Reservation properties through purchase and donations including the welcomes large numbers of sightseers, river rafters and Clay Springs Ranch, the Hunt Ranch, the Cholla Canyon hunters, and the Tribal capital serves as a gateway to world- Ranch, and a property near Truckee, California. -

Everybody Was Talking About the Double Rainbow That Suddenly Switched on Over Hualapai Hilltop As the Sun Set Over the Sandstone Spaghetti Western Horizon

Everybody was talking about the double rainbow that suddenly switched on over Hualapai Hilltop as the sun set over the sandstone Spaghetti Western horizon. In Native American lore, a rainbow is a bridge from one world to another. The occupants of cars pulling into the parking lot for the night at the edge of this thousand-foot-high cliff—the terminus of Indian Road 18 on Arizona’s Havasupai Indian Reservation—all had a sense they were in for one mind-bendy journey. Waking at five in the morning, the Hilltop pilgrims exit their vehicles to begin the three-and-a-half hour trek to the most remote community in the lower 48 states. On the Internet, clickbait listicles proclaim Supai, Arizona among the most remote spots to live In The World. What kind of masochist looks at a destination where the temperature hits 111 in June and thinks “summer vacation”? But hidden at the bottom of this hot winding gorge, in a place gold-greedy Spanish conquistadores just couldn’t be bothered with, is the unlikeliest of unlikelies: Cataract Canyon. The Grand Canyon’s swimming hole. A ribbon of dramatic waterfalls the color of Windex unspooling one after the other amid Jurassic scenery that flies in the face of all reason. The Havasupai (translation: people of the blue-green water) remain the only continuously residing Indians in the Grand Canyon. Today they are sole proprietors of a secret Shangri-la still only reachable via the three h’s: hike, horse, or helicopter. Individuals speak of making as many as 900 calls to the persnickety tribal office to nail a campsite here when the checkered flag falls every February 1st at 8 a.m. -

![4312-50 DEPARTMENT of the INTERIOR National Park Service [NPS-WASO-NAGPRA-12547] [PPWOCRADN0-PCU00RP14.R50000] Notice of Invento](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8318/4312-50-department-of-the-interior-national-park-service-nps-waso-nagpra-12547-ppwocradn0-pcu00rp14-r50000-notice-of-invento-2318318.webp)

4312-50 DEPARTMENT of the INTERIOR National Park Service [NPS-WASO-NAGPRA-12547] [PPWOCRADN0-PCU00RP14.R50000] Notice of Invento

This document is scheduled to be published in the Federal Register on 04/10/2013 and available online at http://federalregister.gov/a/2013-08382, and on FDsys.gov 4312-50 DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR National Park Service [NPS-WASO-NAGPRA-12547] [PPWOCRADN0-PCU00RP14.R50000] Notice of Inventory Completion: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Grand Canyon National Park, Grand Canyon, AZ AGENCY: National Park Service, Interior. ACTION: Notice. SUMMARY: The U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Grand Canyon National Park has completed an inventory of human remains and associated funerary objects, in consultation with the appropriate Indian tribes, and has determined that there is a cultural affiliation between the human remains and associated funerary objects and present-day Indian tribes. Representatives of any Indian tribe that believes itself to be culturally affiliated with the human remains and associated funerary objects may contact Grand Canyon National Park. Repatriation of the human remains and associated funerary objects to the Indian tribes stated below may occur if no additional claimants come forward. DATES: Representatives of any Indian tribe that believes it has a cultural affiliation with the human remains and associated funerary objects should contact Grand Canyon National Park at the address below by [INSERT DATE 30 DAYS AFTER PUBLICATION IN THE FEDERAL REGISTER]. ADDRESSES: David Uberuaga, Superintendent, Grand Canyon National Park, P.O. Box 129, 1 Grand Canyon, AZ 86023, telephone (928) 638-7945. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: Notice is here given in accordance with the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), 25 U.S.C.