Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: Genetics, Pathogenesis, Clinical Manifestations, Diagnosis, and Therapy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anti-MYOZ2 (GW22350F)

3050 Spruce Street, Saint Louis, MO 63103 USA Tel: (800) 521-8956 (314) 771-5765 Fax: (800) 325-5052 (314) 771-5757 email: [email protected] Product Information Anti-MYOZ2 antibody produced in chicken, affinity isolated antibody Catalog Number GW22350F Formerly listed as GenWay Catalog Number 15-288-22350F, Myozenin-2 Antibody. – Storage Temperature Store at 20 °C The product is a clear, colorless solution in phosphate buffered saline, pH 7.2, containing 0.02% sodium azide. Synonyms: Myozenin 2, Calsarcin-1; FATZ-related protein 2 Species Reactivity: Human Product Description Myozenins may serve as intracellular binding proteins Tested Applications: WB involved in linking Z-disk proteins such as alpha-actinin. Recommended Dilutions: Recommended starting dilution gamma-filamin. TCAP/telethonin. LDB3/ZASP and localizing for Western blot analysis is 1:500, for tissue or cell staining calcineurin signaling to the sarcomere. Plays an important 1:200. role in the modulation of calcineurin signaling. May play a role in myofibrillogenesis. Note: Optimal concentrations and conditions for each application should be determined by the user. NCBI Accession number: NP_057683.1 Swiss Prot Accession number: Q9NPC6 Precautions and Disclaimer This product is for R&D use only, not for drug, household, or Gene Information: Human .. MYOZ2 (51778) other uses. Due to the sodium azide content a material Immunogen: Recombinant protein Myozenin 2 safety data sheet (MSDS) for this product has been sent to the attention of the safety officer of your institution. Please Immunogen Sequence: GI # 7706595, sequence 1 - 264 consult the Material Safety Data Sheet for information regarding hazards and safe handling practices. -

Mutations in MYOZ1 As Well As MYOZ2 Encoding the Calsarcins Are Not Associated with Idiopathic and Familial Dilated Cardiomyopathy

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by MDC Repository Repository of the Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine (MDC) Berlin (Germany) http://edoc.mdc-berlin.de/8815/ Mutations in MYOZ1 as well as MYOZ2 encoding the calsarcins are not associated with idiopathic and familial dilated cardiomyopathy Maximilian G. Posch, Andreas Perrot, Rainer Dietz, Cemil Özcelik, Sabine Pankuweit, Volker Ruppert, Anette Richter, and Bernhard Maisch Published in final edited form as: Molecular Genetics and Metabolism. 2007 Jun; 91(2): 207-208 doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2007.02.014 Elsevier (The Netherlands) ► Letter to the editor Mutations in MYOZ1 as well as MYOZ2 encoding the calsarcins are not associated with idiopathic and familial dilated cardiomyopathy Maximilian G. Posch, Andreas Perrot, Rainer Dietz, Cemil Özcelik, Sabine Pankuweit, Volker Ruppert, Anette Richter, and Bernhard Maisch 1 Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin/Cardiology at Campus Buch & Virchow Klinikum, Helios-Kliniken and Max- Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine, Wiltbergstrasse 50, 13125 Berlin, Germany 2 Department of Internal Medicine and Cardiology, Philipps University Marburg, Baldingerstrasse, 35043 Marburg, Germany a very weak mRNA expression of MYOZ1 [5]. Conversely, Dear Editor, MYOZ2 encoding calsarcin-1 is predominantly expressed We have read the article of Arola and colleagues [1] with in cardiomyocytes and to lesser extends in skeletal great interest. The authors report a candidate gene muscle [5,6]. Calsarcin-1 is located at the sarcomeric Z- approach in the MYOZ1 gene encoding calsarcin-2 in 185 disk and interacts with DCM disease genes like telethonin patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy (iDCM). -

Discovery and Systematic Characterization of Risk Variants and Genes For

medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.05.24.21257377; this version posted June 2, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under a CC-BY 4.0 International license . 1 Discovery and systematic characterization of risk variants and genes for 2 coronary artery disease in over a million participants 3 4 Krishna G Aragam1,2,3,4*, Tao Jiang5*, Anuj Goel6,7*, Stavroula Kanoni8*, Brooke N Wolford9*, 5 Elle M Weeks4, Minxian Wang3,4, George Hindy10, Wei Zhou4,11,12,9, Christopher Grace6,7, 6 Carolina Roselli3, Nicholas A Marston13, Frederick K Kamanu13, Ida Surakka14, Loreto Muñoz 7 Venegas15,16, Paul Sherliker17, Satoshi Koyama18, Kazuyoshi Ishigaki19, Bjørn O Åsvold20,21,22, 8 Michael R Brown23, Ben Brumpton20,21, Paul S de Vries23, Olga Giannakopoulou8, Panagiota 9 Giardoglou24, Daniel F Gudbjartsson25,26, Ulrich Güldener27, Syed M. Ijlal Haider15, Anna 10 Helgadottir25, Maysson Ibrahim28, Adnan Kastrati27,29, Thorsten Kessler27,29, Ling Li27, Lijiang 11 Ma30,31, Thomas Meitinger32,33,29, Sören Mucha15, Matthias Munz15, Federico Murgia28, Jonas B 12 Nielsen34,20, Markus M Nöthen35, Shichao Pang27, Tobias Reinberger15, Gudmar Thorleifsson25, 13 Moritz von Scheidt27,29, Jacob K Ulirsch4,11,36, EPIC-CVD Consortium, Biobank Japan, David O 14 Arnar25,37,38, Deepak S Atri39,3, Noël P Burtt4, Maria C Costanzo4, Jason Flannick40, Rajat M 15 Gupta39,3,4, Kaoru Ito18, Dong-Keun Jang4, -

Cardiomyocyte-Specific Deletion of Orai1 Reveals Its Protective Role in Angiotensin-II-Induced Pathological Cardiac Remodeling

cells Article Cardiomyocyte-Specific Deletion of Orai1 Reveals Its Protective Role in Angiotensin-II-Induced Pathological Cardiac Remodeling Sebastian Segin 1,2, Michael Berlin 1,2, Christin Richter 1, Rebekka Medert 1,2, Veit Flockerzi 3, Paul Worley 4, Marc Freichel 1,2 and Juan E. Camacho Londoño 1,2,* 1 Pharmakologisches Institut, Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg, INF 366, 69120 Heidelberg, Germany; [email protected] (S.S.); [email protected] (M.B.); [email protected] (C.R.); [email protected] (R.M.); [email protected] (M.F.) 2 DZHK (German Centre for Cardiovascular Research), Partner Site Heidelberg/Mannheim, 69120 Heidelberg, Germany 3 Experimentelle und Klinische Pharmakologie und Toxikologie, Universität des Saarlandes, 66421 Homburg, Germany; [email protected] 4 The Solomon H. Snyder Department of Neuroscience, Johns Hopkins University, School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD 21205, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +49-6221-54-86863; Fax: +49-6221-54-8644 Received: 26 March 2020; Accepted: 24 April 2020; Published: 28 April 2020 Abstract: Pathological cardiac remodeling correlates with chronic neurohumoral stimulation and abnormal Ca2+ signaling in cardiomyocytes. Store-operated calcium entry (SOCE) has been described in adult and neonatal murine cardiomyocytes, and Orai1 proteins act as crucial ion-conducting constituents of this calcium entry pathway that can be engaged not only by passive Ca2+ store depletion but also by neurohumoral stimuli such as angiotensin-II. In this study, we, therefore, analyzed the consequences of Orai1 deletion for cardiomyocyte hypertrophy in neonatal and adult cardiomyocytes as well as for other features of pathological cardiac remodeling including cardiac contractile function in vivo. -

Genotype-Related Clinical Characteristics and Myocardial Fibrosis and Their Association with Prognosis in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy

Journal of Clinical Medicine Article Genotype-Related Clinical Characteristics and Myocardial Fibrosis and Their Association with Prognosis in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy 1, 2, 3, 3 Hyung Yoon Kim y , Jong Eun Park y, Sang-Chol Lee * , Eun-Seok Jeon , Young Keun On 3, Sung Mok Kim 4 , Yeon Hyeon Choe 4 , Chang-Seok Ki 5, Jong-Won Kim 6 and Kye Hun Kim 1 1 Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Chonnam National University Medical School/Hospital, Gwangju 61469, Korea; [email protected] (H.Y.K.); [email protected] (K.H.K.) 2 Department of Laboratory Medicine, Hanyang University Guri Hospital, Hanyang University College of Medicine, Guri 11923, Korea; [email protected] 3 Department of Internal Medicine, Cardiovascular Imaging Center, Heart, Vascular & Stroke Institute, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul 06351, Korea; [email protected] (E.-S.J.); [email protected] (Y.K.O.) 4 Department of Radiology, Cardiovascular Imaging Center, Heart, Vascular & Stroke Institute, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul 06351, Korea; [email protected] (S.M.K.); [email protected] (Y.H.C.) 5 Green Cross Genome, Yongin 16924, Korea; [email protected] 6 Department of Laboratory Medicine and Genetics, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul 06351, Korea; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +82-2-3410-3419 These authors equally contributed to this work as co-first authors. y Received: 27 April 2020; Accepted: 27 May 2020; Published: 1 June 2020 Abstract: Background: The spectrum of genetic variants and their clinical significance of Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) have been poorly studied in Asian patients. -

PPP3CA Antibody (C-Term) Affinity Purified Rabbit Polyclonal Antibody (Pab) Catalog # Ap13757b

10320 Camino Santa Fe, Suite G San Diego, CA 92121 Tel: 858.875.1900 Fax: 858.622.0609 PPP3CA Antibody (C-term) Affinity Purified Rabbit Polyclonal Antibody (Pab) Catalog # AP13757b Specification PPP3CA Antibody (C-term) - Product Information Application WB,E Primary Accession Q08209 Other Accession P63329, P63328, P48452, NP_001124163.1, NP_000935.1 Reactivity Human Predicted Bovine, Mouse, Rat Host Rabbit Clonality Polyclonal Isotype Rabbit Ig Calculated MW 58688 Antigen Region 438-466 PPP3CA Antibody (C-term) (Cat. #AP13757b) western blot analysis in A375 cell line lysates PPP3CA Antibody (C-term) - Additional (35ug/lane).This demonstrates the PPP3CA Information antibody detected the PPP3CA protein (arrow). Gene ID 5530 Other Names PPP3CA Antibody (C-term) - Background Serine/threonine-protein phosphatase 2B catalytic subunit alpha isoform, CAM-PRP Calcium-dependent, calmodulin-stimulated catalytic subunit, Calmodulin-dependent protein phosphatase. This subunit may have a calcineurin A subunit alpha isoform, role in the calmodulin activation of calcineurin. PPP3CA, CALNA, CNA Dephosphorylates DNM1L, HSPB1 and SSH1. Target/Specificity PPP3CA Antibody (C-term) - References This PPP3CA antibody is generated from rabbits immunized with a KLH conjugated He, Z.H., et al. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. synthetic peptide between 438-466 amino 110(4):761-767(2010) acids from the C-terminal region of human Bailey, S.D., et al. Diabetes Care PPP3CA. 33(10):2250-2253(2010) Chiocco, M.J., et al. Subst Use Misuse Dilution 45(11):1809-1826(2010) WB~~1:1000 Yang, D., et al. Int. J. Mol. Med. 26(1):159-164(2010) Format Bollo, M., et al. PLoS ONE 5 (8), E11925 (2010) Purified polyclonal antibody supplied in PBS : with 0.09% (W/V) sodium azide. -

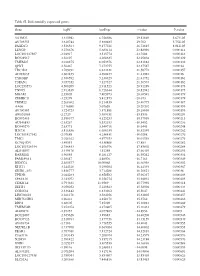

Table SI. Differentially Expressed Genes. Gene Logfc Aveexpr T Value

Table SI. Differentially expressed genes. Gene logFC AveExpr t value P‑value VSTM2L 3.315942 6.756386 29.82869 5.67E‑05 AV703555 3.610744 5.880485 29.702 5.75E‑05 FAXDC2 3.526564 9.177221 26.72815 8.01E‑05 LENG9 3.270676 5.683114 23.88996 0.000114 LOC101927507 ‑2.94917 3.515774 ‑23.7604 0.000116 BC028967 3.56197 4.208635 22.95804 0.000129 TMEM27 3.010875 8.053376 22.81882 0.000132 QPRT 2.56467 7.272755 22.37587 0.00014 TBC1D2 3.789191 6.823331 21.58772 0.000157 AF085835 2.602455 4.690477 21.43982 0.00016 TYROBP 2.386592 5.236329 21.41752 0.000161 TSPAN1 3.057352 7.127327 21.36574 0.000162 LOC253573 4.500209 2.911523 20.91289 0.000173 TNNC1 2.913839 6.726644 20.82942 0.000175 MGAM 2.35805 7.405973 20.68591 0.000179 ZDHHC11 ‑3.25279 5.412875 ‑20.673 0.000179 TRIM22 2.268602 8.214839 20.40775 0.000187 AA06 2.716698 5.07658 20.20202 0.000193 AV700385 3.724723 5.871881 20.18696 0.000193 AW851069 ‑2.2729 5.389451 ‑19.8536 0.000204 BC002465 2.590377 4.125253 19.57939 0.000213 AU146893 ‑2.63267 5.532153 ‑18.9452 0.000236 BC040270 ‑2.63771 5.540716 ‑18.6441 0.000248 H28731 3.816856 6.686159 18.32359 0.000262 LOC101927342 ‑2.07689 4.258431 ‑18.0208 0.000276 TMC1 2.028162 4.977353 18.01518 0.000276 KCNQ1DN ‑3.49551 4.538808 ‑17.883 0.000282 LOC101926934 2.786453 4.106976 17.85802 0.000284 AL043897 3.449478 4.51258 17.66439 0.000293 RARRES1 1.96055 8.281127 16.95242 0.000334 FAM189A1 ‑2.38147 4.48506 ‑16.7163 0.000349 IGDCC4 2.385577 10.00068 16.66958 0.000352 KLK11 3.244328 5.290104 16.44339 0.000367 GRID1‑AS1 1.858777 5.714288 16.26821 0.00038 UPK3B -

Review Article

Artigo de Revisão Cardiomiopatia Hipertrófica: Como as Mutações Levam à Doença? Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: How do Mutations Lead to Disease? Júlia Daher Carneiro Marsiglia e Alexandre Costa Pereira Instituto do Coração, Hospital das Clínicas, Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, SP – Brasil Resumo mutação para o fenótipo clínico e como o genótipo da doença A cardiomiopatia hipertrófica (CMH) é a doença cardíaca se correlaciona com o fenótipo. Além disso, apresentamos dados recentes do perfil genético de pacientes com CMH na genética monogênica mais comum, com uma prevalência 1,3 estimada de 1:500 na população em geral. Clinicamente, população brasileira . CMH é caracterizada por hipertrofia das paredes do ventrículo esquerdo, principalmente o septo, geralmente assimétrica, Genética da Cardiomiopatia Hipertrófica na ausência de qualquer doença cardíaca ou sistêmica que A doença é causada por uma mutação em um dos genes leve a uma hipertrofia secundária. A manifestação clínica que codificam uma proteína do sarcômero, Z-disco ou da doença tem grande heterogeneidade, variando desde moduladores intracelulares de cálcio (Tabela 1). Para genes sintomas leves até insuficiência cardíaca, em idade avançada, sarcoméricos, as mutações identificadas são, em sua maioria, e morte cardíaca súbita, em jovens, sendo causada por uma substituições de um único nucleotídeo e para a maioria dos mutação em um dos genes que codificam uma proteína genes. Acredita-se que a proteína mutante seja incorporada do sarcômero, disco Z ou controladores intracelulares ao sarcômero, exercendo um efeito dominante negativo de cálcio. Apesar de muitos genes e mutações já serem (mutações dominantes negativas). Até agora, a única exceção conhecidos por causar CMH, as vias moleculares que é o gene da Proteína C Cardíaca Ligada à Miosina (MYBPC3), levam ao fenótipo ainda não são claras. -

Calsarcin-2 Deficiency Increases Exercise Capacity in Mice Through Calcineurin/NFAT Activation

Calsarcin-2 deficiency increases exercise capacity in mice through calcineurin/NFAT activation Norbert Frey, … , Hugo A. Katus, Eric N. Olson J Clin Invest. 2008;118(11):3598-3608. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI36277. Research Article The composition of skeletal muscle, in terms of the relative number of slow- and fast-twitch fibers, is tightly regulated to enable an organism to respond and adapt to changing physical demands. The phosphatase calcineurin and its downstream targets, transcription factors of the nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT) family, play a critical role in this process by promoting the formation of slow-twitch, oxidative fibers. Calcineurin binds to calsarcins, a family of striated muscle–specific proteins of the sarcomeric Z-disc. We show here that mice deficient in calsarcin-2, which is expressed exclusively by fast-twitch muscle and encoded by the myozenin 1 (Myoz1) gene, have substantially reduced body weight and fast-twitch muscle mass in the absence of an overt myopathic phenotype. Additionally, Myoz1 KO mice displayed markedly improved performance and enhanced running distances in exercise studies. Analysis of fiber type composition of calsarcin-2–deficient skeletal muscles showed a switch toward slow-twitch, oxidative fibers. Reporter assays in cultured myoblasts indicated an inhibitory role for calsarcin-2 on calcineurin, and Myoz1 KO mice exhibited both an excess of NFAT activity and an increase in expression of regulator of calcineurin 1-4 (RCAN1-4), indicating enhanced calcineurin signaling in vivo. Taken together, these results suggest that calsarcin-2 modulates exercise performance in vivo through regulation of calcineurin/NFAT activity and subsequent alteration of the fiber type composition of skeletal muscle. -

Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy (Type 1–14)

European Journal of Human Genetics (2011) 19; doi:10.1038/ejhg.2010.243 & 2011 Macmillan Publishers Limited All rights reserved 1018-4813/11 www.nature.com/ejhg CLINICAL UTILITY GENE CARD Clinical utility gene card for: hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (type 1–14) Yigal M Pinto*,1, Arthur AAM Wilde1, Ingrid AW van Rijsingen1, Imke Christiaans2, Ronald H Lekanne Deprez2 and Perry M Elliott3 European Journal of Human Genetics (2011) 19, doi:10.1038/ejhg.2010.243; published online 26 January 2011 1. DISEASE CHARACTERISTICS d. Vinculin (VCL) locus 10q22.1-q23. 1.1 Name of the disease (synonyms) e. Alpha-actinin 2 (ACTN2) locus 1q42-q43. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM CMH), familial HCM CMH, f. Myozenin 2 (MYOZ2) locus 4q26-q27. ventricular hypertrophy, hereditary asymmetric septal hypertrophy, 3. Calcium-handling genes: hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy (HOCM), and hypertrophic a. Junctophilin-2 (JPH2) locus 20q12. subaortic stenosis. b. Phospholamban (PLN) locus 6q21.1. Phenocopies/syndromes with only cardiac manifestation possible. 1.2 OMIM# of the disease a. AMP-activated protein kinase (PRKAG2) locus 7q35-q36.36 - 192600 Cardiomyopathy, familial hypertrophic; CMH. Wolff–Parkinson–White syndrome, with or without HCM CMH. 115195 Cardiomyopathy, familial hypertrophic, 2; CMH2. b. Mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) mtDNA. 115196 Cardiomyopathy, familial hypertrophic, 3; CMH3. c. Alpha-galactosidase A (GLA) locus Xq22 - Fabry’s disease. 115197 Cardiomyopathy, familial hypertrophic, 4; CMH4. d. Lysosome-associated membrane protein 2 (LAMP2) locus 600858 Cardiomyopathy, familial hypertrophic, 6; CMH6. Xq24 - Danon’s disease/Wolff–Parkinson–White syndrome. +191044 Cardiomyopathy, familial hypertrophic, 7; CMH7. 608751 Cardiomyopathy, familial hypertrophic, 8; CMH8. 1.4 OMIM# of the gene(s) +191044 Cardiomyopathy, familial hypertrophic, 9; CMH9. -

Mono- and Bi-Allelic Protein Truncating Variants in Alpha-Actinin 2 Cause Cardiomyopathy Through Distinct Mechanisms

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.11.19.389064; this version posted November 20, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. Mono- and bi-allelic protein truncating variants in alpha-actinin 2 cause cardiomyopathy through distinct mechanisms Malene E Lindholm1, David Jimenez-Morales1, Han Zhu1, Kinya Seo1, David Amar1, Chunli Zhao1, Archana Raja1, Roshni Madhvani1*, Cedric Espenel4, Shirley Sutton1, Colleen Caleshu1,6, Gerald J Berry5, Kara S. Motonaga2,3, Kyla Dunn2,3, Julia Platt1,2, Euan A Ashley1,2, Matthew T Wheeler1,2 1. Division of Cardiovascular Medicine, Department of Medicine, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford University, Stanford, USA. 2. Center for Inherited Cardiovascular Diseases, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford University, Stanford, USA 3. Division of Pediatric Cardiology, Department of Pediatrics, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, USA 4. Cell Sciences Imaging Facility, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, USA 5. Department of Pathology, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, USA. 6. GeneMatters bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.11.19.389064; this version posted November 20, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. Abstract Alpha-actinin 2 (ACTN2) anchors actin within cardiac sarcomeres. -

Cardiomyopathy and Arrhythmia Panel, Sequencing and Deletion/Duplication ARUP Test Code 2010183 Cardiomyopathy/Arrhythmia Panel Specimen Whole Blood

Patient Report |FINAL Client: Example Client ABC123 Patient: Patient, Example 123 Test Drive Salt Lake City, UT 84108 DOB 1/23/1984 UNITED STATES Gender: Male Patient Identifiers: 01234567890ABCD, 012345 Physician: Doctor, Example Visit Number (FIN): 01234567890ABCD Collection Date: 00/00/0000 00:00 Cardiomyopathy and Arrhythmia Panel, Sequencing and Deletion/Duplication ARUP test code 2010183 Cardiomyopathy/Arrhythmia Panel Specimen Whole Blood Cardiomyopathy/Arrhythmia Panel Interp Negative INDICATION FOR TESTING Clinical diagnosis of dilated cardiomyopathy. RESULT No pathogenic variants were detected in any of the genes tested. INTERPRETATION No pathogenic variants were identified by massively parallel sequencing of the coding regions and exon-intron boundaries of the genes tested. No large exonic deletions and duplications were identified in the genes tested. This result decreases the likelihood of, but does not exclude, a heritable form of cardiomyopathy or arrhythmia. Please refer to the background information included in this report for a list of the genes analyzed and limitations of this test. RECOMMENDATIONS Medical screening and management should rely on clinical findings and family history. Genetic consultation is recommended. COMMENTS Likely benign and benign variants are not reported. This result has been reviewed and approved by BACKGROUND INFORMATION: Cardiomyopathy and Arrhythmia Panel, Sequencing and Deletion/Duplication CHARACTERISTICS: Inherited cardiomyopathy and arrhythmia disorders are genetically and phenotypically heterogeneous. Phenotypes include hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM), arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC), left ventricular noncompaction (LVNC), catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (CPVT), Brugada syndrome (BrS), long QT syndrome (LQTS), and short QT syndrome (SQTS). EPIDEMIOLOGY: The prevalence of HCM is 1 in 500, DCM is greater than 1 in 500, ARVC is 1 in 1000, LQTS is 1 in 3,000, CPVT is 1 in 10,000, and it is unknown for BrS, LVNC, and SQTS.