“All About the Money?” a Qualitative Interview Study Examining

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Multigenerational Modeling of Money Management

Journal of Financial Therapy Volume 9 Issue 2 Article 5 2018 Multigenerational Modeling of Money Management Christina M. Rosa Brigham Young University Loren D. Marks Brigham Young University Ashley B. LeBaron Brigham Young University See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/jft Part of the Counseling Psychology Commons, Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, Marriage and Family Therapy and Counseling Commons, Social Psychology Commons, and the Social Work Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 License Recommended Citation Rosa, C. M., Marks, L. D., LeBaron, A. B., & Hill, E. (2018). Multigenerational Modeling of Money Management. Journal of Financial Therapy, 9 (2) 5. https://doi.org/10.4148/1944-9771.1164 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Financial Therapy by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Multigenerational Modeling of Money Management Cover Page Footnote We appreciate resources of the "Marjorie Pay Hinckley Award in the Social Sciences and Social Work" at Brigham Young University which funded this research. Authors Christina M. Rosa, Loren D. Marks, Ashley B. LeBaron, and E.Jeffrey Hill This article is available in Journal of Financial Therapy: https://newprairiepress.org/jft/vol9/iss2/5 Journal of Financial Therapy Volume 9, Issue 2 (2018) Multigenerational Modeling of Money Management Christina M. Rosa-Holyoak Loren D. Marks, Ph.D. Brigham Young University Ashley B. LeBaron, M.S. -

Holes in Time: the Autobiography of a Gangster Frank J. Costantino

Holes in Time: The Autobiography of a Gangster Frank J. Costantino © 1979 Library of Congress Catalog Number 79-89370 DEDICATION To Chaplain Max Jones who has the courage to put God first, and the salvation of lost souls as his primary goal. In the day of negative thinking about the role of the prison chaplain, Max Jones stands as a shining example of Christian faith at work behind prison walls. …and to all the staff and directors of Christian Prison Ministries and prison workers everywhere. …and to Dr. Richard Leoffler, Dr. Donald Brown, Curt Bock and Don Horton who believed in me from the very beginning. …and to my wife of 17 years, Cheryl, who went through the whole prison experience with me. FOREWARD Frank was a professional criminal. He deliberately decided to be a thief and a robber. With protection from the underworld, he preyed on the upper world. In eleven years he participated in robberies and thefts totaling eleven million dollars. All this he did with no qualms of conscience. He reasoned that bankers and businessmen stole with their pens. He stole with his guns. He saw no difference. On his first felony conviction he received a sentence of 22 years in prison. There he had plenty of time to think and to reason within himself. The inhumanity that he witnessed demanded that he find out what he wanted to be, a giver or a taker. He reached the conclusion that those who don’t care leave holes in time. His personal encounter with Christ in the office of Chaplain Max Jones settled all the issues. -

1. Summer Rain by Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss by Chris Brown Feat T Pain 3

1. Summer Rain By Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss By Chris Brown feat T Pain 3. You Know What's Up By Donell Jones 4. I Believe By Fantasia By Rhythm and Blues 5. Pyramids (Explicit) By Frank Ocean 6. Under The Sea By The Little Mermaid 7. Do What It Do By Jamie Foxx 8. Slow Jamz By Twista feat. Kanye West And Jamie Foxx 9. Calling All Hearts By DJ Cassidy Feat. Robin Thicke & Jessie J 10. I'd Really Love To See You Tonight By England Dan & John Ford Coley 11. I Wanna Be Loved By Eric Benet 12. Where Does The Love Go By Eric Benet with Yvonne Catterfeld 13. Freek'n You By Jodeci By Rhythm and Blues 14. If You Think You're Lonely Now By K-Ci Hailey Of Jodeci 15. All The Things (Your Man Don't Do) By Joe 16. All Or Nothing By JOE By Rhythm and Blues 17. Do It Like A Dude By Jessie J 18. Make You Sweat By Keith Sweat 19. Forever, For Always, For Love By Luther Vandros 20. The Glow Of Love By Luther Vandross 21. Nobody But You By Mary J. Blige 22. I'm Going Down By Mary J Blige 23. I Like By Montell Jordan Feat. Slick Rick 24. If You Don't Know Me By Now By Patti LaBelle 25. There's A Winner In You By Patti LaBelle 26. When A Woman's Fed Up By R. Kelly 27. I Like By Shanice 28. Hot Sugar - Tamar Braxton - Rhythm and Blues3005 (clean) by Childish Gambino 29. -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Goldfrapp (Medley) Can't Help Falling Elvis Presley John Legend In Love Nelly (Medley) It's Now Or Never Elvis Presley Pharrell Ft Kanye West (Medley) One Night Elvis Presley Skye Sweetnam (Medley) Rock & Roll Mike Denver Skye Sweetnam Christmas Tinchy Stryder Ft N Dubz (Medley) Such A Night Elvis Presley #1 Crush Garbage (Medley) Surrender Elvis Presley #1 Enemy Chipmunks Ft Daisy Dares (Medley) Suspicion Elvis Presley You (Medley) Teddy Bear Elvis Presley Daisy Dares You & (Olivia) Lost And Turned Whispers Chipmunk Out #1 Spot (TH) Ludacris (You Gotta) Fight For Your Richard Cheese #9 Dream John Lennon Right (To Party) & All That Jazz Catherine Zeta Jones +1 (Workout Mix) Martin Solveig & Sam White & Get Away Esquires 007 (Shanty Town) Desmond Dekker & I Ciara 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z Ft Beyonce & I Am Telling You Im Not Jennifer Hudson Going 1 3 Dog Night & I Love Her Beatles Backstreet Boys & I Love You So Elvis Presley Chorus Line Hirley Bassey Creed Perry Como Faith Hill & If I Had Teddy Pendergrass HearSay & It Stoned Me Van Morrison Mary J Blige Ft U2 & Our Feelings Babyface Metallica & She Said Lucas Prata Tammy Wynette Ft George Jones & She Was Talking Heads Tyrese & So It Goes Billy Joel U2 & Still Reba McEntire U2 Ft Mary J Blige & The Angels Sing Barry Manilow 1 & 1 Robert Miles & The Beat Goes On Whispers 1 000 Times A Day Patty Loveless & The Cradle Will Rock Van Halen 1 2 I Love You Clay Walker & The Crowd Goes Wild Mark Wills 1 2 Step Ciara Ft Missy Elliott & The Grass Wont Pay -

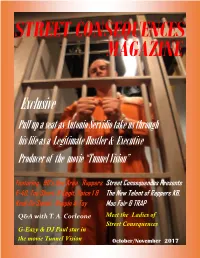

G-Eazy & DJ Paul Star in the Movie Tunnel Vision October/November 2017 in the BAY AREA YOUR VIEW IS UNLIMITED

STREET CONSEQUENCES MAGAZINE Exclusive Pull up a seat as Antonio Servidio take us through his life as a Legitimate Hustler & Executive Producer of the movie “Tunnel Vision” Featuring 90’s Bay Area Rappers Street Consequences Presents E-40, Too Short, B-Legit, Spice 1 & The New Talent of Rappers KB, Keak Da Sneak, Rappin 4-Tay Mac Fair & TRAP Q&A with T. A. Corleone Meet the Ladies of Street Consequences G-Eazy & DJ Paul star in the movie Tunnel Vision October/November 2017 IN THE BAY AREA YOUR VIEW IS UNLIMITED October/November 2017 2 October /November 2017 Contents Publisher’s Word Exclusive Interview with Antonio Servidio Featuring the Bay Area Rappers Meet the Ladies of Street Consequences Street Consequences presents new talent of Rappers October/November 2017 3 Publisher’s Words Street Consequences What are the Street Consequences of today’s hustling life- style’s ? Do you know? Do you have any idea? Street Con- sequences Magazine is just what you need. As you read federal inmates whose stories should give you knowledge on just what the street Consequences are. Some of the arti- cles in this magazine are from real people who are in jail because of these Street Consequences. You will also read their opinion on politics and their beliefs on what we, as people, need to do to chance and make a better future for the up-coming youth of today. Stories in this magazine are from big timer in the games to small street level drug dealers and regular people too, Hopefully this magazine will open up your eyes and ears to the things that are going on around you, and have to make a decision that will make you not enter into the game that will leave you dead or in jail. -

From Zones of Conflict Comes Music for Peace

From zones of conflict comes music for peace. What is Fambul Tok? Around a crackling bonfire in a remote village, the war finally ended. Seven years since the last bullet was fired, a decade of fighting in The artists on this album have added their voices to a high-energy, Sierra Leone found resolution as people stood and spoke. Some had urgent call for forgiveness and deep dialogue. They exemplify the perpetrated terrible crimes against former friends. Some had faced creative spirit that survives conflict, even war. From edgy DJs and horrible losses: loved ones murdered, limbs severed. But as they soulful singer-songwriters, from hard-hitting reggae outfits to told their stories, admitted their wrongs, forgave, danced, and sang transnational pop explorers, they have seen conflict and now sow together, true reconciliation began. This is the story of “Fambul Tok” peace. They believe in the power of ordinary people - entire com- (Krio for “family talk”), and it is a story the world needs to hear. munities ravaged by war - to work together to forge a lasting peace. They believe in Fambul Tok. Fambul Tok originated in the realization that peace can’t be imposed from the outside, or the top down. Nor does it need to be. The com- munity led and owned peacebuilding in Sierra Leone is teaching us that communities have within them the resources they need for their own healing. Join the fambul at WAN FAMBUL O N E FA M I LY FAMBULTOK.COM many voices ... Wi Na Wan Fambul BajaH + DRY EYE Crew The groundbreaking featuring Rosaline Strasser-King (LadY P) and Angie 4:59 grassroots peacebuilding of Nasle Man AbjeeZ 5:33 the people of Sierra Leone Say God Idan RaicHel Project has also been documented featuring VieuX Farka Toure 4:59 in the award-winning film Ba Kae Vusi MAHlasela 5:05 Fambul Tok, and in its Guttersnipe BHI BHiman 6:52 companion book, Fambul Shim El Yasmine 5:10 Tok. -

It's Good to See You're Awake

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses Spring 5-17-2013 It's Good to See You're Awake Maurice C. Ruffin University of New Orleans, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Part of the Fiction Commons Recommended Citation Ruffin, Maurice C., "It's Good to See You're Awake" (2013). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 1666. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/1666 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. It’s Good to See You’re Awake A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in Film & Theatre Creative Writing by Maurice Carlos Ruffin B.A. University of New Orleans, 2000 J.D. Loyola University School of Law, 2003 May, 2013 Acknowledgements This collection is dedicated to Tanzanika, my wife, best friend, and muse, and to Barb Johnson, who gave me More of this World. -

8123 Songs, 21 Days, 63.83 GB

Page 1 of 247 Music 8123 songs, 21 days, 63.83 GB Name Artist The A Team Ed Sheeran A-List (Radio Edit) XMIXR Sisqo feat. Waka Flocka Flame A.D.I.D.A.S. (Clean Edit) Killer Mike ft Big Boi Aaroma (Bonus Version) Pru About A Girl The Academy Is... About The Money (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug About The Money (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug, Lil Wayne & Jeezy About Us [Pop Edit] Brooke Hogan ft. Paul Wall Absolute Zero (Radio Edit) XMIXR Stone Sour Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) Ninedays Absolution Calling (Radio Edit) XMIXR Incubus Acapella Karmin Acapella Kelis Acapella (Radio Edit) XMIXR Karmin Accidentally in Love Counting Crows According To You (Top 40 Edit) Orianthi Act Right (Promo Only Clean Edit) Yo Gotti Feat. Young Jeezy & YG Act Right (Radio Edit) XMIXR Yo Gotti ft Jeezy & YG Actin Crazy (Radio Edit) XMIXR Action Bronson Actin' Up (Clean) Wale & Meek Mill f./French Montana Actin' Up (Radio Edit) XMIXR Wale & Meek Mill ft French Montana Action Man Hafdís Huld Addicted Ace Young Addicted Enrique Iglsias Addicted Saving abel Addicted Simple Plan Addicted To Bass Puretone Addicted To Pain (Radio Edit) XMIXR Alter Bridge Addicted To You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Avicii Addiction Ryan Leslie Feat. Cassie & Fabolous Music Page 2 of 247 Name Artist Addresses (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. Adore You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miley Cyrus Adorn Miguel Adorn Miguel Adorn (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel Adorn (Remix) Miguel f./Wiz Khalifa Adorn (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel ft Wiz Khalifa Adrenaline (Radio Edit) XMIXR Shinedown Adrienne Calling, The Adult Swim (Radio Edit) XMIXR DJ Spinking feat. -

Rotunda Library, Special Collections, and Archives

Longwood University Digital Commons @ Longwood University Rotunda Library, Special Collections, and Archives 11-5-2014 Rotunda - Vol 93, No 10 - Nov 5, 2014 Longwood University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.longwood.edu/rotunda Recommended Citation Longwood University, "Rotunda - Vol 93, No 10 - Nov 5, 2014" (2014). Rotunda. Paper 2125. http://digitalcommons.longwood.edu/rotunda/2125 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Library, Special Collections, and Archives at Digital Commons @ Longwood University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Rotunda by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Longwood University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LONGWOOD UNIVERSITY The Rotunda Wednesday, November 5, 2014 Participating in “No-shave November” since 1920 Delta Zeta’s Turtle Tug WMLU Concerns Men’s Basketball BY NATALIE JOSEPH BY KIRA ZIMNEY BY HALLE PARKER Sisters raise over $650 from their annual Concerns were raised by Longwood’s radio The team prepares for their upcoming season philanthropy event. station at the SGA meeting. and opening exhibition against HSC. PAGE 6 PAGE 5 PAGE 14 Candlelight Vigil for Hannah Graham PHOTO BY STAFF PHOTOGRAPHER MARLISHA STEWART Students gather around President Reveley for the candlelight vigil that was held in memory of Hannah Graham. Read more on page 9. vol. 93, issue no.10 2 NEWS TheRotundaOnline.com EDITORIAL BOARD 2014 Card Access in Wygal Hall BY RONALD MOUNTCASEL CONTRIBUTOR Wygal is not a new building and can be traced back to the 1970’s. Much like Bedford, Wygal houses The grey side door leading into expensive equipment ranging from the first floor of Wygal has not computers, sound production been opening, neither is the red mixing consoles and instruments, door that opens to the staircase some of which belong to students. -

Managing Beyond Extrinsic Rewards to Thrive in the Real Estate Industry

Not Just About the Money: Managing Beyond Extrinsic Rewards to Thrive in the Real Estate Industry by Edwin En-Wei Liang B.A., Economics, 2006 Columbia University Submitted to the Program in Real Estate Development in Conjunction with the Center for Real Estate in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Real Estate Development at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology September, 2012 ©2012 Edwin En-Wei Liang All rights reserved The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Signature of Author____________________________________________________________ Center for Real Estate July 30, 2012 Certified by___________________________________________________________________ Gloria Schuck Lecturer, Center for Real Estate Thesis Supervisor Accepted by___________________________________________________________________ David Geltner Chair, MSRED Committee, Interdepartmental Degree Program in Real Estate Development 1 2 Not Just About the Money: Managing Beyond Extrinsic Rewards to Thrive in the Real Estate Industry by Edwin En-Wei Liang Submitted to the Program in Real Estate Development in Conjunction with the Center for Real Estate on July 30, 2012 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Real Estate Development ABSTRACT Companies in the 21st century are increasingly relying on knowledge workers—people who put to work what they have learned from systematic education as opposed to manual skills—for value creation. Knowledge workers are the link to all of the company’s other investments, managing and processing them to achieve company objectives. But because people, rather than things, are the means of value creation, they are mobile and must exercise choice to join, stay, and work hard for a particular company above all others. -

Selling Or Selling Out?: an Exploration of Popular Music in Advertising

Selling or Selling Out?: An Exploration of Popular Music in Advertising Kimberly Kim Submitted to the Department of Music of Amherst College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts with honors. Faculty Advisor: Professor Jason Robinson Faculty Readers: Professor Jenny Kallick Professor Jeffers Engelhardt Professor Klara Moricz 05 May 2011 Table of Contents Acknowledgments............................................................................................................... ii Chapter 1 – Towards an Understanding of Popular Music and Advertising .......................1 Chapter 2 – “I’d Like to Buy the World a Coke”: The Integration of Popular Music and Advertising.........................................................................................................................14 Chapter 3 – Maybe Not So Genuine Draft: Licensing as Authentication..........................33 Chapter 4 – Selling Out: Repercussions of Product Endorsements...................................46 Chapter 5 – “Hold It Against Me”: The Evolution of the Music Videos ..........................56 Chapter 6 – Cultivating a New Cultural Product: Thoughts on the Future of Popular Music and Advertising.......................................................................................................66 Works Cited .......................................................................................................................70 i Acknowledgments There are numerous people that have provided me with invaluable -

BENNY GOLSON NEA Jazz Master (1996)

1 Funding for the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Program NEA Jazz Master interview was provided by the National Endowment for the Arts. BENNY GOLSON NEA Jazz Master (1996) Interviewee: Benny Golson (January 25, 1929 - ) Interviewer: Anthony Brown with recording engineer Ken Kimery Date: January 8-9, 2009 Repository: Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution Description: Transcript, 119 pp. Brown: Today is January 8th, 2009. My name is Anthony Brown, and with Ken Kimery we are conducting the Smithsonian National Endowment for the Arts Oral History Program interview with Mr. Benny Golson, arranger, composer, elder statesman, tenor saxophonist. I should say probably the sterling example of integrity. How else can I preface my remarks about one of my heroes in this music, Benny Golson, in his house in Los Angeles? Good afternoon, Mr. Benny Golson. How are you today? Golson: Good afternoon. Brown: We’d like to start – this is the oral history interview that we will attempt to capture your life and music. As an oral history, we’re going to begin from the very beginning. So if you could start by telling us your first – your full name (given at birth), your birthplace, and birthdate. Golson: My full name is Benny Golson, Jr. Born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The year is 1929. Brown: Did you want to give the exact date? Golson: January 25th. For additional information contact the Archives Center at 202.633.3270 or [email protected] 2 Brown: That date has been – I’ve seen several different references. Even the Grove Dictionary of Jazz had a disclaimer saying, we originally published it as January 26th.