Histories and New Directions Within the Youth Climate Movement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Climate Solutions” Issue, Spring 2008 Change Our Sources of Electricity Arjun Makhijani Is an Engineer Who’S Been Thinking About Energy for More Than 35 Years

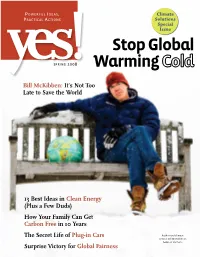

Powerful Ideas, Climate PractIcal actIons Solutions Special Issue Stop Global yes!sPrIng 2008 Warming Bill McKibben: It’s Not Too Late to Save the World 13 Best Ideas in Clean Energy (Plus a Few Duds) How Your Family Can Get Carbon Free in 10 Years The Secret Life of Plug-in Cars Author and climate activist Bill McKibben at home in Vermont Surprise Victory for Global Fairness “One way or another, the choice will be made by our generation, but it will affect life on earth for all generations to come.” Lester Brown , Earth Policy Institute Tsewang Norbu was selected by his Himalayan village to be trained at the Barefoot College of Tilonia, India, in the installation and repair of solar photovoltaic units. All solar units were brought to the village across the 18,400- foot Khardungla Pass by yak and on villagers’ backs. photo by barefoot photographers of tilonia. copyright 2008 barefoot college, tilonia, rajastan, india, barefootcollege.org yesm a g a z i! n e www.yesmagazine.org Reprinted from the “Climate Solutions” Issue, Spring 2008 Change Our Sources of Electricity Arjun Makhijani is an engineer who’s been thinking about energy for more than 35 years. When he heard a presentation ISSUE 45 claiming we needed to go fossil-carbon free by 2050, he didn’t YES! THEME GUIDE think it could be done. X years of research later, he’s changed his mind. His book, Carbon-Free and Nuclear-Free: A Roadmap for U.S. Energy Policy, tells exactly how it can be done. Here’s how Makhijani sees the energy supply changing for buildings, CLIMATE SOLUTIONStransportation and electricity. -

2019 (November 2018 – October 2019)

QUAKER EARTHCARE WITNESS ANNUAL REPORT November 2018 - October 2019 Affirming our essential unity with nature Above: Friends visit Jim and Kathy Kessler’s restored native plant habitat during the Friends General Conference Gathering in Iowa. OUR WORK THIS YEAR Quaker Earthcare Witness has grown over the last 32 years out of a deepening sense of QUAKER ACTIVISM & spiritual connection with the natural world. From this has come an urgency to work on the critical EDUCATION issues of our times, including climate and environmental justice. This year we are excited to see that more people This summer we sponsored the QEW Earthcare Center are mobilizing around the eco-crises than ever before, at the Friends General Conference annual gathering, both within and beyond the Religious Society of Friends. including scheduling and hosting presentations every afternoon, showcasing what Friends are doing regarding With your help, Quaker Earthcare Witness is Earthcare, displaying resources to share, and giving responding to the growing need for inspiration talks. We offered presentations on climate justice, and support for Friends and Meetings. indigenous concerns, eco-spirituality, activism and hope, permaculture, and children’s education. We also QEW is the largest network of Friends working on sponsored a field trip to a restored prairie (thanks to Jim Earthcare today. We work to inspire spirit-led action Kessler, QEW Steering Committee member, who planned toward ecological sustainability and environmental the trip and restored, along with his wife Kathy, this plot justice. We provide inspiration and resources to Friends of Iowa prairie). throughout North America by distributing information in our newsletter, BeFriending Creation, on our website Our General Secretary, Communications Coordinator, quakerearthcare.org and through social media. -

Appendix C: High School Summit Notes High School Student Climate Change Summit, October 19, 2019

Appendix C: High School Summit Notes High School Student Climate Change Summit, October 19, 2019 Built Environment Facilitator: Izzy, Lucena, Aileen Lawrence, Mayani, Emma, Yelena, Talon Participants: Grace, Sydney, Alyssa, Darius Question: What does our city look like when it’s carbon free? More trees, solar panels in populated areas More local food Electric car charging, replacement of gas stations Emphasis on recycling, making it more available More reusable packaging and less of it Getting families and older generation on board, annoy them into it Forests on buildings, plant walls @ DOCO More parks means more biking Grey water system, saving water, refilter water Water recycling? Conservation? Compost bins in school cafeteria, reusable plates for meals, easily recyclable materials Urban farms, bring to west sac Have more native plants on landscape Using old affordable materials to build housing, involve contractors and architects Useful landscapes, garden and drought resistant plants Rock garden among schools Bring plants into classrooms Community gardens/arboretum/green spaces Drought tolerant landscapes of California native plants Preserving current landscapes and planting more trees, mitigation More farmers markets, more farm to fork, more local food More solar panels and renewable energy Energy efficient buildings, vertical gardens outside of and on top of buildings with drought resistant and native plants, community gardens, farm to fork self sufficient communities for homeless and low income Wiser land development, school and -

Duane Elgin Endorsements for Choosing Earth “Choosing Earth Is the Most Important Book of Our Time

CHOOSING EARTH Humanity’s Great Transition to a Mature Planetary Civilization Duane Elgin Endorsements for Choosing Earth “Choosing Earth is the most important book of our time. To read and dwell within it is an awakening experience that can activate both an ecological and spiritual revolution.” —Jean Houston, PhD, Chancellor of Meridian University, philosopher, author of The Possible Human, Jump Time, Life Force and many more. “A truly essential book for our time — from one of the greatest and deepest thinkers of our time. Whoever is concerned to create a better future for the human family must read this book — and take to heart the wisdom it offers.” —Ervin Laszlo is evolutionary systems philosopher, author of more than one hundred books including The Intelligence of the Cosmos and Global Shift. “This may be the perfect moment for so prophetic a voice to be heard. Sobered by the pandemic, we are recognizing both the fragility of our political arrangements and the power of our mutual belonging. As Elgin knows, we already possess the essential ingredient —our capacity to choose.” —Joanna Macy, author of Active Hope: How to Face the Mess We're in Without Going Crazy, is root teacher of the Work That Reconnects and celebrated in A Wild Love for the World: Joanna Macy and the Work of Our Time. “Duane Elgin has thought hard — and meditated long — about what it will take for humanity to evolve past our looming ecological bottleneck toward a future worth building. There is wisdom in these pages to light the way through our dark and troubled times.” —Richard Heinberg is one of the world’s foremost advocates for a shift away from reliance on fossil fuels; author of Our Renewable Future, Peak Everything, and The End of Growth. -

Contesting Climate Change

CONTESTING CLIMATE CHANGE: CIVIL SOCIETY NETWORKS AND COLLECTIVE ACTION IN THE EUROPEAN UNION A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Jennifer Leigh Hadden August 2011 © 2011 Jennifer Leigh Hadden CONTESTING CLIMATE CHANGE: CIVIL SOCIETY NETWORKS AND COLLECTIVE ACTION IN THE EUROPEAN UNION Jennifer Leigh Hadden, Ph.D. Cornell University, 2011 Civil society organizations choose vastly different forms of collective action to try to influence European politics: everything from insider lobbying to disruptive protest, from public education to hunger strikes. Using network analysis and qualitative interviewing, my research emphasizes that patterns of inter-organizational relations influence organizational decisions to use one of these strategies. They do this by structuring the information and resources available to actors, as well as by diffusing strategies across connected actors. This is particularly true when networks are segmented into two distinct components, as I find in the European climate change network. In this network, organizations using contentious ‘outsider’ strategies are only loosely linked to those ‘insiders’ behaving conventionally in Brussels. These findings are policy relevant because current scholarship and policy recommendations tend to assume that increased civil society participation in transnational policy-making will increase democratic legitimacy. But my network data and qualitative interviews suggests that the emergence of a coalition of organizations engaging solely in contentious outsider action reflects the development and diffusion of a new and highly critical strand of climate change politics. I further argue that this type of contentious civil society ‘spillover’ can actually slow the pace of development of climate change policy and of European integration more generally. -

Schnews Reporter in Latin Meanwhile Just Down the Hill, Less Than Three This Week the Pine Gap 4 Begun Their Two Week America Writes

The Rougher Guide To Guatemala Mind the Gap WAKE UP!! FOR THE BENEFIT OF THE TAPE, IT'S YER... One roaming SchNEWS reporter in Latin Meanwhile just down the hill, less than three This week the Pine Gap 4 begun their two week America writes... minutes walk away, lies ‘tourist town’. It is full Supreme Court trial in Alice Springs, charged “The incredibly touristy Guatemalan town of of Westerners hanging around with their Lonely with breaking into the Pine Gap secret US/NSA/ San Pedro La Laguna is a world of parallels. At Planets, blissfully unaware of what is happen- CIA spy base in central Australia for a Citizen’s the top of the hill away from the lakeside sits ing in the local population as they smoke their Inspection in December 2005. the Escuela Ofi cial Humberto Corzo Guzmán, incredibly cheap weed and wait for the next Pine Gap, run by less than friendly US military a local free school that has been educating the Hollywood movie to play in one of the many corporation Raytheon, is an important node of the indigenous Mayan children of the area for hun- Western-owned bars. satellite system used by the US for operations such dreds of years. Since October last year, a group La Municipalidad, represented by a nice old as the bombing of Iraq and Afghanistan. The four of parents and teachers have been occupying the chap called Antonio Chavajay Yojcom has done Christian anti-war campaigners face seven year Friday 1st June 2007Free/Do na tion Issue 590 school in order to prevent the local government what all modern-thinking governments do and is sentences, after the Attorney General Philip Rud- (la Municipalidad) tearing it down to build a 3- in the process of suing the parents and teachers dock consented to the fi rst-ever use of the cold-war storey supermarket… something the farmers of occupying the school. -

City Research Online

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Mercea, D. (2013). Probing the Implications of Facebook use for the organizational form of social movement organizations. Information, Communication and Society, 16(8), pp. 1306-1327. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2013.770050 This is the unspecified version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/3045/ Link to published version: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2013.770050 Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] 1 Probing the Implications of Facebook Use for the Organisational Form of Social Movement Organisations "This is an Author's Original Manuscript of an article submitted for consideration in Information, Communication & Society [copyright Taylor & Francis]; Information, Communication & Society is available online at http://www.tandfonline.com/ 10.1080/1369118X.2013.770050. This article examines the use of Facebook by social movement organisations and the ramifications from that usage for their organisational form. -

Arab Youth Climate Movement

+ Arab Youth Climate Movement UNEP – ROWA Regional Stakeholders Meeting + From Rio to Doha + Rio+20 + UNEP’s Role in Civil Society engagement Build on the Rio+20 outcomes para. 88h and 99 in particular, and to make sure that we see progress: The need for an international convention on procedural rights, as well as regional conventions with compliance mechanisms. The need for UNEP to show leadership when implementing its new mandate under para 88h and to promote mechanisms for a strengthening of public participation in International Environmental Governance, not only within its own processes but also across the whole IEG (as it has done in the past with its Bali Guidelines). + + Sept 2012 - Birth of the Arab Youth Climate Movement (AYCM) + + Arab Youth Climate Movement The Arab Youth Climate Movement (AYCM) is an independent body that works to create a generation-wide movement across the Middle East & North Africa to solve the climate crisis, and to assess and support the establishment of legally binding agreements to deal with climate change issue within international negotiations. The AYCM has a simple vision – we want to be able to enjoy a stable climate similar to that which our parents and grandparents enjoyed. + COP18 + Day of Action – Key Messages Climate change is a threat to all life on the planet. Unfortunately, the Arab countries have so far been the only region that is ignoring the threat of climate change. Arab leaders must fulfill their responsibilities towards future generations, by working constructively and strongly on the national and international level to achieve greenhouse gas emission reduction in the region and globally. -

C H a P T E R Iv

CHAPTER IV Moving forward: youth taking action and making a difference The combined acumen and involvement of all individuals, from regular citizens to scientific experts, will be needed as the world moves forward in implementing climate change miti- gation and adaptation measures and promot- ing sustainable development. Young people must be prepared to play a key role within this context, as they are the ones who will live to R IV experience the long-term impact of today’s crucial decisions. TE The present chapter focuses on the partici- pation of young people in addressing climate change. It begins with a review of the various mechanisms for youth involvement in environ- HAP mental advocacy within the United Nations C system. A framework comprising progressive levels of participation is then presented, and concrete examples are provided of youth in- volvement in climate change efforts around the globe at each of these levels. The role of youth organizations and obstacles to partici- pation are also examined. PROMOTING YOUTH ture. In addition to their intellectual contribution and their ability to mobilize support, they bring parTICipaTION WITHIN unique perspectives that need to be taken into account” (United Nations, 1995, para. 104). THE UNITED NATIONS The United Nations has long recognized the Box IV.1 importance of youth participation in decision- making and global policy development. Envi- The World Programme of ronmental issues have been assigned priority in Action for Youth on the recent decades, and a number of mechanisms importance of participation have been established within the system that The World Programme of Action for enables youth representatives to contribute to Youth recognizes that the active en- climate change deliberations. -

AYCC 2018 IMPACT REPORT WE’RE FIGHTING for CLIMATE JUSTICE WE’RE FIGHTING for CLIMATE JUSTICE Our Mission Young People Want to Grow up in a Kinder, Safer World

AYCC 2018 IMPACT REPORT WE’RE FIGHTING FOR CLIMATE JUSTICE WE’RE FIGHTING FOR CLIMATE JUSTICE Our Mission Young people want to grow up in a kinder, safer world. But old and dirty fossil fuels like coal and gas are polluting our air and warming our planet,and the companies profiting off this damage are manipulating our politicians. To ensure a safe climate for our generation, powered by clean renewable energy, we’ve got to build unprecedented people power, led by those with most at stake, to squash the dirty dollars of the fossil fuel lobby. WHAT IS CLIMATE JUSTICE? The climate crisis is unjust, because those that have done the least to cause the problem, feel the effects first and worst. And we think this is unfair. Working for climate justice means all people, regardless of where they’re born, their age, or the colour of their skin - everyone has access to a safe climate and healthy environment, and are empowered to create solutions to the climate crisis that work for them. The climate crisis is a moment to rethink the way this world operates, ensuring we don’t create the same problems in the future. If we embed justice and sustainability at the heart of this transition, we can create a brighter future for all. WHAT WE DO: SEED INDIGENOUS YOUTH CLIMATE NETWORK: Led by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youth, Seed is a branch of the AYCC that is empowering Indigenous young people to lead climate justice campaigns and create change in their communities. CAMPAIGNS THAT WIN: We work together as a movement to make a difference through campaigns that reduce climate pollution, move Australia beyond fossil fuels and supercharge the transition to 100% renewable energy. -

Climate Justice Education: from Social Movement Learning to Schooling

Climate justice education Climate justice education: From social movement learning to schooling Authors McGregor, C., Scandrett, E., Christie, B. and Crowther, J. Abstract In recent years, the insurgent discourse of climate justice has offered an alternative to the dominant discourse of sustainable development, which has arguably constructed climate change as a global ‘post- political’ problem, with the effect of erasing its ideological features. However, even climate justice can be considered a contested term, meaning different things to different social actors. Accordingly, this chapter offers a theoretical analysis of the challenges and opportunities for a climate justice education (CJE), which prioritises the distinctive educative and epistemological contributions of social movements, and extends analysis of such movements, by considering how the learning they generate might inform CJE in schools. Regarding the latter, we focus on the Scottish context, both because it represents the context in which our own knowledge claims are grounded, and because the mainstreaming of Learning for Sustainability (LfS) in policy presents an ostensibly sympathetic context for exploring climate justice. We conceptualise CJE as a process of hegemonic struggle, and in doing so, consider recursive ‘engagement with’—as opposed to ‘withdrawal from’—the state (Mouffe, 2013), via schooling, to be a legitimate dimension of social movement learning. 1 Christie, Crowther, McGregor and Scandrett Education must look like the society we dream of. It must be revolutionary and transform reality. From the Margareta Declaration on Climate Change Introduction The overarching aim of this chapter is to offer a theoretical analysis of the challenges and opportunities for a climate justice education (CJE), which both recognises the distinctive educative and epistemological contributions of social movements, and positions itself critically both ‘in and against’ the Scottish educational policy contexts of the Curriculum for Excellence (CfE) and Learning for Sustainability (LfS). -

Climate Futures: Youth Perspectives

Conference briefing Climate Futures: Youth Perspectives February 2021 William Finnegan #clClimateFutures cumberlandlodge.ac.uk @CumberlandLodge Foreword This briefing document has been prepared to guide and inform discussions at Climate Futures: Youth Perspectives, the virtual conference we are convening from 9 to 18 March 2021. It provides an independent review of current research and thinking, and information about action being taken to address the risks associated with our rapidly changing climate. In March, we are convening young people from schools, colleges and universities across the UK, together with policymakers, charity representatives, activists, community practitioners and academics, for a fortnight of intergenerational dialogue on some of the biggest challenges facing the planet today. We are providing a platform for young people to express their views, visions and expectations for climate futures, ahead of the 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26) in Glasgow, this November. Ideas and perspectives from the Cumberland Lodge conference will be consolidated into a summary report, to be presented to the Youth4Climate: Driving Ambition meeting (Pre-COP26) in Milan this September. We are grateful to our freelance Research Associate, Bill Finnegan, for preparing this resource for us. Bill will be taking part in our virtual conference and writing our final report. The draft report will be reviewed and refined at a smaller consultation involving conference participants and further academics and specialists in the field of climate change, before being published this summer. I hope that you find this briefing useful, both for the conference discussions and your wider work and study. I look forward to seeing you at the conference.