Paradigm Shift in the View of Duodji in the 21Stcentury

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tipi Instructions

Tipi Instructions Hello and thanks for buying one of our Tipi Tents. Here are the instructions for the best way to put it up, take it down and how to store when not in use. We’ve provided a step-by-step picture guide for you to follow along with the written instructions. At the bottom of these instructions we’ve added some advice and tips on how to get years of good service out of your tent by looking after it properly. Enjoy! And don’t hesitate to contact us if you have any questions, good ideas or better ways of doing it. Once you’ve erected your tent, we would love to see your Boutique Camping pictures, so please send them to us at [email protected]. They may even feature on our blog or Facebook page! Putting up a Tipi Tent Some general advice • We advise having 2 people to erect the tent, as it will of course simplify the process. By all means, you can put it up on your own, but of course the more the merrier, easier and quicker! • Find a flat piece of land, with ample space to comfortably put up your tent remembering to include room for the guy ropes • To prevent damaging the groundsheet, remove all sharp objects from the area. Things like stones and roots etc • Be careful when creating tension with the guy ropes, always try to keep the tension even, and never over do it. Be firm but gentle. • Before you peg out the tent, make sure all zips are closed, and check again when you adjust the guy ropes • Peg out the guy ropes in line with the tent seams How to Put Up Your Tipi A1)Open all bags and lay out all parts. -

The Sámi People and Their Culture the Sámi Or Saami Were Also Called Lapps Or Laplanders by the English

The Sámi people and their culture The Sámi or Saami were also called Lapps or Laplanders by the English. Sámi people consider the English terms derogatory. The Sámi are recognized as the only indigenous people of Europe. They have lived in Norway, Sweden, Finland and Russia. Their origins are Finno‐Ugric, a Hungarian and Yugra (Urals) past, inhabiting the Sápmi region. Today, the region encompasses large parts of Norway and Sweden, northern parts of Finland, and the Murmansk Oblast (Kola Peninsula) of Russia. The Sámi people have their own language, culture and customs that differ from others around them. This has caused the Sámi social problems and culture clashes. As we learned from our Sámi culture presentation and a quote from ‐religiousstudiesproject.com the following: “The history between the Sámi and the Norwegian government has left a stain on the Sámi for generations: The Norwegianization policy undertaken by the Norwegian government from the 1850s up until the Second World War resulted in the apparent loss of Sami language and assimilation of the coastal Sami as an ethnically‐distinct people into the northern Norwegian population. Together with the rise of an ethno‐political movement since the 1970s, however, Sami culture has seen a revitalization of language, cultural activities, and ethnic identity (Brattland 2010:31).” Note: Suggested readings, ‐laits.utexas.edu, a 19‐part series by the University of Texas entitled “Sámi Culture.” The other reading is‐ unsr.vtaulicorpuz.org. It is a report by the United Nations on the rights of indigenous people such as the Sámi. Reindeer are the Sámi key element to how they live. -

Tent Inspection

Tent Guide Information referenced from the 2015 Frederick County Fire Prevention Code A Tent is defined as a structure, enclosure or shelter, with or without sidewalls or drops, constructed of fabric or pliable material supported by any manner except by air or the contents that it protects. All Tents: • A permit issued by the Frederick County Fire Marshal’s office shall be required for tents over 900 square feet not being used for recreational camping purposes. (Frederick County fire Prevention Code section 107.2 Permit Required.) • A detailed site and floor plan for tents with occupant load of 50 or more shall be required with each application for approval. The tent floor plan shall indicate details of means of egress, seating capacity, arrangement of seating and location and types of heating and electrical equipment. (Frederick County fire Prevention Code section 3103.6 Construction documents.) • An unobstructed fire break passageway or fire road not less than 12 feet wide and free from guy ropes or other obstructions shall be maintained on all sides of all tents unless otherwise approved by the fire code official. (Frederick County fire Prevention Code section 3103.8.6 Fire break.) • A certificate from an approved laboratory stating that the materials used in tent meet the flame- retardant criteria needed to pass NFPA Test Method 1 or Test Method 2. (Frederick County fire Prevention Code section 3104.2 Flame propagation performance treatment.) • Approved “No Smoking” signs shall be conspicuously posted. (Frederick County fire Prevention Code section 3104.6 Smoking.) • At least one 5lb. multipurpose 2A 10BC portable fire extinguisher shall be hung and tagged within 75 ft of travel distance. -

THE SUN, the MOON and FIRMAMENT in CHUKCHI MYTHOLOGY and on the RELATIONS of CELESTIAL BODIES and SACRIFICE Ülo Siimets

THE SUN, THE MOON AND FIRMAMENT IN CHUKCHI MYTHOLOGY AND ON THE RELATIONS OF CELESTIAL BODIES AND SACRIFICE Ülo Siimets Abstract This article gives a brief overview of the most common Chukchi myths, notions and beliefs related to celestial bodies at the end of the 19th and during the 20th century. The firmament of Chukchi world view is connected with their main source of subsistence – reindeer herding. Chukchis are one of the very few Siberian indigenous people who have preserved their religion. Similarly to many other nations, the peoples of the Far North as well as Chukchis personify the Sun, the Moon and stars. The article also points out the similarities between Chukchi notions and these of other peoples. Till now Chukchi reindeer herders seek the supposed help or influence of a constellation or planet when making important sacrifices (for example, offering sacrifices in a full moon). According to the Chukchi religion the most important celestial character is the Sun. It is spoken of as an individual being (vaúrgún). In addition to the Sun, the Creator, Dawn, Zenith, Midday and the North Star also belong to the ranks of special (superior) beings. The Moon in Chukchi mythology is a man and a being in one person. It is as the ketlja (evil spirit) of the Sun. Chukchi myths about several stars (such as the North Star and Betelgeuse) resemble to a great extent these of other peoples. Keywords: astral mythology, the Moon, sacrifices, reindeer herding, the Sun, celestial bodies, Chukchi religion, constellations. The interdependence of the Earth and celestial as well as weather phenomena has a special meaning for mankind for it is the co-exist- ence of the Sun and Moon, day and night, wind, rainfall and soil that creates life and warmth and provides the daily bread. -

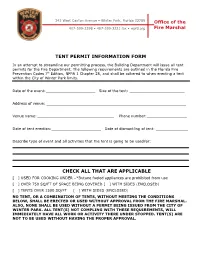

Tent & Events Under a Tent Permit Application

343 West Canton Avenue • Winter Park, Florida 32789 Office of the 407-599-3298 • 407-599-3231 fax • wpfd.org Fire Marshal TENT PERMIT INFORMATION FORM In an attempt to streamline our permitting process, the Building Department will issue all tent permits for the Fire Department. The following requirements are outlined in the Florida Fire Prevention Codes 7th Edition, NFPA 1 Chapter 25, and shall be adhered to when erecting a tent within the City of Winter Park limits. Date of the event: Size of the tent: Address of venue: Venue name: Phone number: _ Date of tent erection: Date of dismantling of tent: Describe type of event and all activities that the tent is going to be used for: CHECK ALL THAT ARE APPLICABLE [ ] USED FOR COOKING UNDER –*Butane fueled appliances are prohibited from use [ ] OVER 750 SQ/FT OF SPACE BEING COVERED [ ] WITH SIDES (ENCLOSED) [ ] TENTS OVER 1500 SQ/FT [ ] WITH SIDES (ENCLOSED) NO TENT, OR A COMBINATION OF TENTS, WITHOUT MEETING THE CONDITIONS BELOW, SHALL BE ERECTED OR USED WITHOUT APPROVAL FROM THE FIRE MARSHAL. ALSO, NONE SHALL BE USED WITHOUT A PERMIT BEING ISSUED FROM THE CITY OF WINTER PARK. ALL TENT(S) NOT COMPLING WITH THESE REQUIREMENTS, WILL IMMEDIATELY HAVE ALL WORK OR ACTIVITY THERE UNDER STOPPED. TENT(S) ARE NOT TO BE USED WITHOUT HAVING THE PROPER APPROVAL. TENTS USED FOR COOKING 1. Permits for all tents used to cook under, shall be submitted no later than five business days prior to the erection of the tents. An inspection at least 90 minutes prior to the cooking operations and subject to all fees per the City of Winter Park may be required. -

Nordic Tipis – a Home for Big and Small Adventures ROOTS

ADVENTURE Nordic tipis – a home for big and small adventures ROOTS THE PEOPLE OF THE SUN AND WIND The Sami are the only indigenous people in Europe. They used to live as nomadic trackers, hunters and reindeer keepers. Their country Sápmi extends over northern Scandinavia and parts of Russia. The tough climate, the long winter and nature’s tribulations were part of these people’s everyday life. The lifecycle of the reindeer was also theirs and they accompanied their animals to their summer and winter grazing grounds. Traditionally, the Sami lived in a “kåta” in the winter. The focal point of the tent was the fire which gave them heat and light and a feel of homeliness. Our company was started in Moskosel, a little village in Swedish Lapland, where the Sami heritage is ever present. Our hope is that, when you choose a Tentipi Nordic tipi, you will feel the same closeness to the elements as the indigenous people do. Separating the reindeer – an activity steeped in cultural heritage that is still a central part of reindeer husbandry © Peter Rosén CONTENT 04 Adventure tent range 24 Stove and fire equipment 26 Tent accessories 31 Sustainability 32 Handicraft and material 34 Crucial features 36 Event tents 38 Tentipi Camp 39 Further reading Wanted: a home in nature The idea came to me when I was sitting by a stream, far out in the wilds of Lapland. Tired and sweaty after a long day of exciting canoeing, what I really wanted to do was socialise with my friends while eating dinner and chatting around a fire. -

Spring Into the New! Three New Exhibitions at the American

Contact: Caroline Rossy Communications & Operations Manager Tel: 215-389-1776, Fax: 215-389-7701 Email: [email protected] -- FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Spring into the New! Three New Exhibitions at the American Swedish Historical Museum The Sami People of Alaska and Sami Walking with Reindeer, opening April 14 Enchanting Transparency, the ASHM’s Swedish Glass Collection, now on view Philadelphia, PA- Spring is time to refresh, a time for out with the old and in with the new. In that spirit, the American Swedish Historical Museum is excited to announce our spring exhibitions, The Sami Reindeer People of Alaska and Sami—Walking with Reindeer, along with a new permanent exhibit, Enchanting Transparency, featuring the Museum’s collection of Swedish glass, now on view in the renovated Linneaus Kalm Gallery. Opening April 14 and on view through August 26, 2018, The Sami Reindeer People of Alaska and Sami—Walking with Reindeer both explore the story of the Sami (the indigenous people of Scandinavia) journeying to North America 100 years ago, as well as those living in Scandinavia today. The indigenous peoples of northern Scandinavia—the Sami—offer a cultural lens for exploring the themes of home and heritage. The Sami Reindeer People of Alaska, borrowed from the Sami Cultural Center of North America in Minnesota, challenges notions of where people come from and how they identify themselves as they journey to new lands. The Sami Reindeer People of Alaska takes us alongside Sami families traveling 10,000 miles to Alaska during the 1890s. As part of a U.S.- sponsored effort to introduce domesticated reindeer to Alaska, these families journeyed by boat, train, and sledge to settle themselves and their reindeer in a familiar environment but strange country. -

7 Person Teepee Tent

ASSEMBLY INSTRUCTIONS MODEL W790, 11’8”x 11’8” 7 Person Teepee Tent SAFETY WARNING - CARE DOs AND DO NOTs DO NOT LEAVE YOUR TENT SET UP IN DIRECT SUNLIGHT LONGER THAN NECESSARY. THE SUN’S ULTRAVIOLET (UV) LIGHT DEGRADES ALMOST EVERY FABRIC AND MATERIAL. IF LEFT IN SUNLIGHT FOR PROLONGED PERIODS EVERYONE WHO USES THIS TENT SHOULD READ THIS MANUAL AND BECOME FAMILIAR WITH ALL SAFETY WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS FOR SAFE USE, ASSEMBLY, CARE, MAINTENANCE, OF TIME, FABRIC WILL FADE AND WEAKEN. DO NOT STORE TENT ON CONCRETE FLOOR. DO NOT SPRAY THE AND STORAGE. KEEP THIS MANUAL SO YOU CAN REFER TO IT LATER. TENT WITH INSECTICIDE. Your tent is water repellent, however, it is not waterproof. During heavy rain, some leakage may occur. Keep DANGER CARBON MONOXIDE GAS WILL KILL YOU objects from touching the inside of the tent. Such objects may cause leakage at point of contact. If seam leakage Stoves, heaters, grills, lantern, candles, and other fuel-burning devices that burn propane, natural gas, charcoal, kerosene, coal, or other fuels produce a toxic gas called carbon monoxide. Because carbon monoxide gas is invisible, odorless, and colorless, a dangerous level of carbon occurs, it can be controlled by applying a seam sealer compound. monoxide gas can accumulate in a tent which cannot be detected by sight, smell, or taste. For these reasons: EXERCISE CARE WHEN USING ELECTRIC DEVICES IN AND NEAR TENTS. • DO NOT use matches, lighters, stoves, heaters, grills, lanterns, candles, cooking equipment, or other fuel-burning devices inside or near a tent. • DO NOT build fires inside or near a tent. -

W Hat Is a Yurt?

Nonfiction IS A YU AT R H T ? W by Lily Ryan PAIRED READ Treehouses STRATEGIES & SKILLS Comprehension Phonics Strategy: Ask and Answer Diphthongs oi, oy Questions Skill: Cause and Effect Content Standards Science Vocabulary Practice of Science above, balance, build, fall, knew, money, section, toward Word count: 332** Photography Credit: (bkgd) Thomas Lehne/lotuseaters/Alamy Stock Photo, (t) flocu/Shutterstock.com **The total word count is based on words in the running text and headings only. Numerals and words in captions, labels, diagrams, charts, and sidebars are not included. mheducation.com/prek-12 Copyright © 2014 McGraw-Hill Education. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written consent of McGraw-Hill Education, including, but not limited to, network storage or transmission, or broadcast for distance learning. Send all inquiries to: McGraw-Hill Education Two Penn Plaza New York, New York 10121 ISBN: 978-0-02-119681-4 MHID: 0-02-119681-8 Printed in the of America 11 12 13 14 15 DOC 22 21 20 19 18 D Genre Nonfiction Essential Question How do things get built? IS A YU AT R H T ? W by Lily Ryan Chapter 1 Who Lives in a Yurt? .............. 2 Chapter 2 How Are Yurts Built? .............. 6 Chapter 3 Do People Build Yurts Today? ....... 9 Respond to Reading .............. 12 PAIRED READ Treehouses ................ 13 (bkgd) Vincenzo Lombardo/Photographer’s Choice RF/Getty flocu/Shutterstock.com Choice (c) Images, Lombardo/Photographer’s Vincenzo (bkgd) Focus on Science.......... -

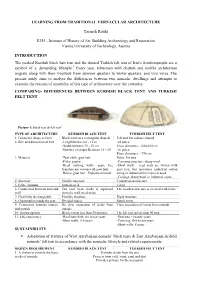

Learning from Traditional Vernacular Architecture

LEARNING FROM TRADITIONAL VERNACULAR ARCHITECTURE Taraneh Rouhi E251 - Institute of History of Art, Building Archaeology and Restoration Vienna University of Technology, Austria INTRODUCTION The peaked Kurdish black hair tent and the domed Turkish felt tent of Iran's frontierspeople are a symbol of a demanding lifestyle.1 Every year, tribesmen with chattels and mobile architecture migrate along with their livestock from summer quarters to winter quarters, and vice versa. The present study aims to analyse the differences between two nomadic dwellings and attempts to examine the reasons of suitability of this type of architecture over the centuries. COMPARING- DIFFERENCES BETWEEN KURDISH BLACK TENT AND TURKISH FELT TENT Picture 1: black tent & felt tent2 TYPE OF ARCHITECTURE KURDISH BLACK TENT TURKISH FELT TENT 1. Geometric shape or form Black tent has a rectangular shaped Felt tent has a dome shaped 2. Size and dimension of tent -Length between 6 - 13 m -24 poles: -Width between 25 - 35 cm Floor diameters ~ 600-650 cm -Number of stripes Between 15 – 25 -26 poles: Floor diameters ~ 750 cm 3. Material -Tent cloth: goat hair Poles: firs tree -Poles: poplar -Covering structure: sheep wool -Reed matting walls: apple tree -Short walls – reed mats are woven with branches are woven with goat hair goat hair, but nowadays industrial cotton -Ropes: goat hair - Equipment inside string or industrial thin ropes is used -Cordage: sheep wool or industrial ropes 4. Structure Tensile structure Compression structure 5. Poles’ forming Straight or X Curve 6. Connection between roof and The roof (tent cloth) is separated The wooden structure is covered with felts wall from the wall (reed mats) 7. -

Because It Rains

BECAUSE IT RAINS EMERGING PROFESSIONAL TRAVEL SCHOLARSHIP 2018 AIA Seattle Laura Bartunek RAIN topic of investigation I am nothing if not accustomed to rain. A child of the Pacific Northwest, I grew up somewhere between high precipitation and light evening showers. Even now I feel my eyes are best suited to the overcast grey, and I sleep most soundly to the pattering of rain against my shingled roof. You could say my life has been shaped to embrace the inevitable gale. Yet, as a designer I perpetually find myself defending my ideas from water. We are taught that the origin of architecture is shelter. Architecture began with a roof pitched overhead to shield the sacred interior. We continue in this history by creating shells that are shaped and nestled into the landscape – spaces that frame views, but ultimately barriers to create refuge. We stitch, tape, seal, caulk, gasket and screen our shells, perfecting the recipes of our skins to inhibit even the slightest trace of precipitation. And in so doing, our spaces resist and endure. But in our enthusiasm to protect might we not have missed something? What if our fundamental understanding of water was different? What if our common sense was reversed and water was friend, not foe. What would our buildings - our cities - look like? Would buildings drink water and grow? Would they take off their coats and shake the rain from their skirts? Would urban centers transform their streets, their roads, their walkways with rain, creating cities of storms? How might we work with water, instead of against it? For my AIA Seatle Emerging Professional Travel Scholarship, I propose to study the potential of rain. -

There's a World Class Nordic Tipi to Suit

From family adventures to extreme expeditions — there’s a world class Nordic tipi to suit you www.tentipi.com FIRE EARTH AIR WATER Embrace the elements — Tentipi® Nordic tipis let you embrace the elements like no other tents. At the same time, they protect you from the elements like no other tents. No one offers such stability, high performance fabrics, time-saving features and versatility. And who else lets you have the elemental comfort of an open fire inside your tent? These are what makes it so much more convenient and comfortable to enjoy the outdoor lifestyle with Tentipi®. You are sheltered so well from the wind, rain, snow, cold, sun and insects. And this is why our tents are named after such stirring examples of the natural elements. Our prestigious Adventure Nordic tipis, ‘Safir’, ‘Zirkon’ and ‘Onyx’, are named after minerals whose toughness was forged over four billion years ago by the elemental forces of a cooling earth. Sami heritage The Sami kåta and the Indian teepee are in principle the same solution for living close to nature. A simple cone- shaped frame of wooden poles was covered with animal hides, with an opening at the top to let out smoke. Very quickly the nomadic reindeer herding Sami people of northern Scandinavia had a wind-resistant and relatively sophisticated home that was easy to keep warm. The principle was simple: the fire created warmth and the hides kept it in. The fire also provided light and a homely atmosphere. Cooking and smoking food, drying clothing and other household chores could easily be done inside.