The Aboriginal Tent Embassy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tipi Instructions

Tipi Instructions Hello and thanks for buying one of our Tipi Tents. Here are the instructions for the best way to put it up, take it down and how to store when not in use. We’ve provided a step-by-step picture guide for you to follow along with the written instructions. At the bottom of these instructions we’ve added some advice and tips on how to get years of good service out of your tent by looking after it properly. Enjoy! And don’t hesitate to contact us if you have any questions, good ideas or better ways of doing it. Once you’ve erected your tent, we would love to see your Boutique Camping pictures, so please send them to us at [email protected]. They may even feature on our blog or Facebook page! Putting up a Tipi Tent Some general advice • We advise having 2 people to erect the tent, as it will of course simplify the process. By all means, you can put it up on your own, but of course the more the merrier, easier and quicker! • Find a flat piece of land, with ample space to comfortably put up your tent remembering to include room for the guy ropes • To prevent damaging the groundsheet, remove all sharp objects from the area. Things like stones and roots etc • Be careful when creating tension with the guy ropes, always try to keep the tension even, and never over do it. Be firm but gentle. • Before you peg out the tent, make sure all zips are closed, and check again when you adjust the guy ropes • Peg out the guy ropes in line with the tent seams How to Put Up Your Tipi A1)Open all bags and lay out all parts. -

The Sámi People and Their Culture the Sámi Or Saami Were Also Called Lapps Or Laplanders by the English

The Sámi people and their culture The Sámi or Saami were also called Lapps or Laplanders by the English. Sámi people consider the English terms derogatory. The Sámi are recognized as the only indigenous people of Europe. They have lived in Norway, Sweden, Finland and Russia. Their origins are Finno‐Ugric, a Hungarian and Yugra (Urals) past, inhabiting the Sápmi region. Today, the region encompasses large parts of Norway and Sweden, northern parts of Finland, and the Murmansk Oblast (Kola Peninsula) of Russia. The Sámi people have their own language, culture and customs that differ from others around them. This has caused the Sámi social problems and culture clashes. As we learned from our Sámi culture presentation and a quote from ‐religiousstudiesproject.com the following: “The history between the Sámi and the Norwegian government has left a stain on the Sámi for generations: The Norwegianization policy undertaken by the Norwegian government from the 1850s up until the Second World War resulted in the apparent loss of Sami language and assimilation of the coastal Sami as an ethnically‐distinct people into the northern Norwegian population. Together with the rise of an ethno‐political movement since the 1970s, however, Sami culture has seen a revitalization of language, cultural activities, and ethnic identity (Brattland 2010:31).” Note: Suggested readings, ‐laits.utexas.edu, a 19‐part series by the University of Texas entitled “Sámi Culture.” The other reading is‐ unsr.vtaulicorpuz.org. It is a report by the United Nations on the rights of indigenous people such as the Sámi. Reindeer are the Sámi key element to how they live. -

Tent Inspection

Tent Guide Information referenced from the 2015 Frederick County Fire Prevention Code A Tent is defined as a structure, enclosure or shelter, with or without sidewalls or drops, constructed of fabric or pliable material supported by any manner except by air or the contents that it protects. All Tents: • A permit issued by the Frederick County Fire Marshal’s office shall be required for tents over 900 square feet not being used for recreational camping purposes. (Frederick County fire Prevention Code section 107.2 Permit Required.) • A detailed site and floor plan for tents with occupant load of 50 or more shall be required with each application for approval. The tent floor plan shall indicate details of means of egress, seating capacity, arrangement of seating and location and types of heating and electrical equipment. (Frederick County fire Prevention Code section 3103.6 Construction documents.) • An unobstructed fire break passageway or fire road not less than 12 feet wide and free from guy ropes or other obstructions shall be maintained on all sides of all tents unless otherwise approved by the fire code official. (Frederick County fire Prevention Code section 3103.8.6 Fire break.) • A certificate from an approved laboratory stating that the materials used in tent meet the flame- retardant criteria needed to pass NFPA Test Method 1 or Test Method 2. (Frederick County fire Prevention Code section 3104.2 Flame propagation performance treatment.) • Approved “No Smoking” signs shall be conspicuously posted. (Frederick County fire Prevention Code section 3104.6 Smoking.) • At least one 5lb. multipurpose 2A 10BC portable fire extinguisher shall be hung and tagged within 75 ft of travel distance. -

THE SUN, the MOON and FIRMAMENT in CHUKCHI MYTHOLOGY and on the RELATIONS of CELESTIAL BODIES and SACRIFICE Ülo Siimets

THE SUN, THE MOON AND FIRMAMENT IN CHUKCHI MYTHOLOGY AND ON THE RELATIONS OF CELESTIAL BODIES AND SACRIFICE Ülo Siimets Abstract This article gives a brief overview of the most common Chukchi myths, notions and beliefs related to celestial bodies at the end of the 19th and during the 20th century. The firmament of Chukchi world view is connected with their main source of subsistence – reindeer herding. Chukchis are one of the very few Siberian indigenous people who have preserved their religion. Similarly to many other nations, the peoples of the Far North as well as Chukchis personify the Sun, the Moon and stars. The article also points out the similarities between Chukchi notions and these of other peoples. Till now Chukchi reindeer herders seek the supposed help or influence of a constellation or planet when making important sacrifices (for example, offering sacrifices in a full moon). According to the Chukchi religion the most important celestial character is the Sun. It is spoken of as an individual being (vaúrgún). In addition to the Sun, the Creator, Dawn, Zenith, Midday and the North Star also belong to the ranks of special (superior) beings. The Moon in Chukchi mythology is a man and a being in one person. It is as the ketlja (evil spirit) of the Sun. Chukchi myths about several stars (such as the North Star and Betelgeuse) resemble to a great extent these of other peoples. Keywords: astral mythology, the Moon, sacrifices, reindeer herding, the Sun, celestial bodies, Chukchi religion, constellations. The interdependence of the Earth and celestial as well as weather phenomena has a special meaning for mankind for it is the co-exist- ence of the Sun and Moon, day and night, wind, rainfall and soil that creates life and warmth and provides the daily bread. -

Witnessing the Apology

PHOTOGRAPHIC Essay Witnessing the Apology Juno gemes Photographer, Hawkesbury River I drove to Canberra alight with anticipation. ry, the more uncomfortable they became — not The stony-hearted policies of the past 11 years with me and this work I was committed to — but had been hard: seeing Indigenous organisations with themselves. I had long argued that every whose births I had witnessed being knee-capped, nation, including Australia, has a conflict history. taken over, mainstreamed; the painful ‘histori- Knowing can be painful, though not as painful as cal denialism’ (Manne 2008:27). Those gains memory itself. lost at the behest of Howard’s basically assimila- En route to Canberra, I stopped in Berrima tionist agenda. Yet my exhibition Proof: Portraits — since my schooldays, a weathervane of the from the Movement 1978–2003 toured around colonial mind. Here apprehension was evident. the country from the National Portrait Gallery in The woman working in a fine shop said to me, Canberra in 2003 to 11 venues across four States ‘I don’t know about this Apology’. She recounted and two countries, finishing up at the Museum of how her husband’s grandfather had fallen in love Sydney in 2008, and proved to be a rallying point with an Aboriginal woman and been turfed out for those for whom the Reconciliation agenda of his family in disgrace. Pain shadowed so many would never go away. For those growing pockets hearts in how many families across the nation? of resistance that could not be extinguished. ‘You might discover something for you in this’, Prime Minister Kevin Rudd’s new Labor Gov- I replied. -

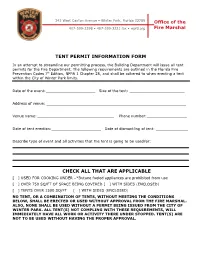

Tent & Events Under a Tent Permit Application

343 West Canton Avenue • Winter Park, Florida 32789 Office of the 407-599-3298 • 407-599-3231 fax • wpfd.org Fire Marshal TENT PERMIT INFORMATION FORM In an attempt to streamline our permitting process, the Building Department will issue all tent permits for the Fire Department. The following requirements are outlined in the Florida Fire Prevention Codes 7th Edition, NFPA 1 Chapter 25, and shall be adhered to when erecting a tent within the City of Winter Park limits. Date of the event: Size of the tent: Address of venue: Venue name: Phone number: _ Date of tent erection: Date of dismantling of tent: Describe type of event and all activities that the tent is going to be used for: CHECK ALL THAT ARE APPLICABLE [ ] USED FOR COOKING UNDER –*Butane fueled appliances are prohibited from use [ ] OVER 750 SQ/FT OF SPACE BEING COVERED [ ] WITH SIDES (ENCLOSED) [ ] TENTS OVER 1500 SQ/FT [ ] WITH SIDES (ENCLOSED) NO TENT, OR A COMBINATION OF TENTS, WITHOUT MEETING THE CONDITIONS BELOW, SHALL BE ERECTED OR USED WITHOUT APPROVAL FROM THE FIRE MARSHAL. ALSO, NONE SHALL BE USED WITHOUT A PERMIT BEING ISSUED FROM THE CITY OF WINTER PARK. ALL TENT(S) NOT COMPLING WITH THESE REQUIREMENTS, WILL IMMEDIATELY HAVE ALL WORK OR ACTIVITY THERE UNDER STOPPED. TENT(S) ARE NOT TO BE USED WITHOUT HAVING THE PROPER APPROVAL. TENTS USED FOR COOKING 1. Permits for all tents used to cook under, shall be submitted no later than five business days prior to the erection of the tents. An inspection at least 90 minutes prior to the cooking operations and subject to all fees per the City of Winter Park may be required. -

Alycia Ashcroft 1 Page Suggestions for New Electorate Name

Suggestion 37 Alycia Ashcroft 1 page Suggestions for new electorate name: 1. Eleanor Harding 1934 – 1996 a. Equal rights and education campaigner Eleanor Harding was a respected community figure who poured her energy into achieving a better deal for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. She was especially passionate about women's issues and education. Eleanor was a member of the Aborigines Advancement League and the Victorian branch of the Federal Council for the Advancement of Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders (FCAATSI) in the 1960s. During this time she worked on a national campaign to ensure equal rights for Indigenous Australians. She is also known for her work in pushing for improving Indigenous Australians rights through constitutional change. The 1967 Referendum on the Constitution ensued. As an executive member of the National Aboriginal and Islander Women's Council, Eleanor was part of women's rights advocacy group that protested against the Bicentennial celebrations in 1970 in Sydney and the women’s contingent that travelled to Canberra in support of the 1972 Aboriginal Tent Embassy protest. 2. Faith Bandler, AC 1918 -2015 a. Faith Bandler played an important role in establishing the civil rights movement in Australia and dedicated her life to equality and fairness for Indigenous Australians. Faith Bandler, AC, was a remarkable woman who was passionate in campaigning for the rights of Indigenous Australians and South Sea Islanders. 3. Pearl Gibbs 1901 – 1983 a. Pearl Gibbs was one of the most prominent female Indigenous female activists within the Aboriginal movement in the early 20th century. As a member of the Aborigines Progressive Association, she was involved with various protest events such as the 1938 Day of Mourning. -

A Reflection on the First 30 Days of the 1972 Aboriginal Embassy

A REFLECTION ON THE FIRST THIRTY DAYS OF THE EMBASSY By Gary Foley From the book: Foley, G, Schaap, A & Howell, E 2013, The Aboriginal Tent Embassy. [electronic resource] : Sovereignty, Black Power, Land Rights and the State, Hoboken : Taylor and Francis, 2013 It was in the first four weeks of the 1972 Aboriginal Embassy protest that a small group of Aboriginal activists rapidly improvised and transformed an opportunistic accident into an effective protest that captured world attention and brought significant historical and political change in Australia.1 What had begun as a simple knee-jerk reaction to an Australia Day statement on Land Rights by the Australian Prime Minister, resulted in the accidental discovery that there was no law in Canberra that prevented the activists from staging a protest camp on the lawns of Parliament. The swift action of the activists to take advantage of this situation enabled them to gain political advantage over the McMahon Government in the propaganda war and political battle that would take place over the next six months. Exactly how these events unfolded has never been written about in detail. Even in Scott Robinson’s (ch.1 in this volume) or in Kathy Lothian’s (2007) accounts, the crucial early days are not fully examined. Yet if we are to gain a better understanding of why the Aboriginal Embassy was able to become such an effective protest action, it is important to gain an awareness of how it all began. So in this chapter I will examine some of the factors that enabled the already highly effective group of Aboriginal activists from the Redfern Black Power collective to create a highly effective challenge to the political power structure and force a major change in policy. -

Critical Australian Indigenous Histories

Transgressions critical Australian Indigenous histories Transgressions critical Australian Indigenous histories Ingereth Macfarlane and Mark Hannah (editors) Published by ANU E Press and Aboriginal History Incorporated Aboriginal History Monograph 16 National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Transgressions [electronic resource] : critical Australian Indigenous histories / editors, Ingereth Macfarlane ; Mark Hannah. Publisher: Acton, A.C.T. : ANU E Press, 2007. ISBN: 9781921313448 (pbk.) 9781921313431 (online) Series: Aboriginal history monograph Notes: Bibliography. Subjects: Indigenous peoples–Australia–History. Aboriginal Australians, Treatment of–History. Colonies in literature. Australia–Colonization–History. Australia–Historiography. Other Authors: Macfarlane, Ingereth. Hannah, Mark. Dewey Number: 994 Aboriginal History is administered by an Editorial Board which is responsible for all unsigned material. Views and opinions expressed by the author are not necessarily shared by Board members. The Committee of Management and the Editorial Board Peter Read (Chair), Rob Paton (Treasurer/Public Officer), Ingereth Macfarlane (Secretary/ Managing Editor), Richard Baker, Gordon Briscoe, Ann Curthoys, Brian Egloff, Geoff Gray, Niel Gunson, Christine Hansen, Luise Hercus, David Johnston, Steven Kinnane, Harold Koch, Isabel McBryde, Ann McGrath, Frances Peters- Little, Kaye Price, Deborah Bird Rose, Peter Radoll, Tiffany Shellam Editors Ingereth Macfarlane and Mark Hannah Copy Editors Geoff Hunt and Bernadette Hince Contacting Aboriginal History All correspondence should be addressed to Aboriginal History, Box 2837 GPO Canberra, 2601, Australia. Sales and orders for journals and monographs, and journal subscriptions: T Boekel, email: [email protected], tel or fax: +61 2 6230 7054 www.aboriginalhistory.org ANU E Press All correspondence should be addressed to: ANU E Press, The Australian National University, Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected], http://epress.anu.edu.au Aboriginal History Inc. -

Indigenous Significance Not Significant Enough

TITLE: Indigenous significance not significant enough AUTHOR: Andrew Macintosh & Deb Wilkinson PUBLICATION: OnLine Opinion PUBLICATION DATE: 13/03/06 The Prime Minister’s speech to the National Press Club on the eve of Australia Day early this year attracted much comment. Most of this concentrated on his call for “root and branch renewal” of the way Australian history is taught in our schools and the fact that the remarks were another in a long line of not so subtle attacks on the so-called “cultural elites” and “politically correct” ideologues that apparently dominate our educational institutions. Tucked away in the PM’s speech however, was a fascinating reference to Indigenous history. According to the Prime Minister, Indigenous history should be taught as part of the “whole national inheritance”. He also indicated that his Government is willing to “meet the Indigenous people more than half way” on the road to reconciliation. On the basis of these statements, one would expect the Howard Government to have sought to promote the conservation and understanding of Indigenous heritage. It is part of our “national inheritance” and, as such, is surely deserving of equal billing with our colonial and post-Federation history. Apparently not. A brief look at what the Howard Government has included on the National Heritage List indicates what the Prime Minister actually meant when he advocated a more rigorous teaching of the Australian narrative. The National Heritage List was established in January 2004 and currently includes 24 places that are supposed to have “outstanding heritage value to the nation”. Only five of these have anything to do with Indigenous heritage. -

Nordic Tipis – a Home for Big and Small Adventures ROOTS

ADVENTURE Nordic tipis – a home for big and small adventures ROOTS THE PEOPLE OF THE SUN AND WIND The Sami are the only indigenous people in Europe. They used to live as nomadic trackers, hunters and reindeer keepers. Their country Sápmi extends over northern Scandinavia and parts of Russia. The tough climate, the long winter and nature’s tribulations were part of these people’s everyday life. The lifecycle of the reindeer was also theirs and they accompanied their animals to their summer and winter grazing grounds. Traditionally, the Sami lived in a “kåta” in the winter. The focal point of the tent was the fire which gave them heat and light and a feel of homeliness. Our company was started in Moskosel, a little village in Swedish Lapland, where the Sami heritage is ever present. Our hope is that, when you choose a Tentipi Nordic tipi, you will feel the same closeness to the elements as the indigenous people do. Separating the reindeer – an activity steeped in cultural heritage that is still a central part of reindeer husbandry © Peter Rosén CONTENT 04 Adventure tent range 24 Stove and fire equipment 26 Tent accessories 31 Sustainability 32 Handicraft and material 34 Crucial features 36 Event tents 38 Tentipi Camp 39 Further reading Wanted: a home in nature The idea came to me when I was sitting by a stream, far out in the wilds of Lapland. Tired and sweaty after a long day of exciting canoeing, what I really wanted to do was socialise with my friends while eating dinner and chatting around a fire. -

Right Wrongs Toolkit Part 8 Teacher Resources.Pdf

INFORMATION FOR TEACHERS: QUESTIONS FROM THE INFORMATION TOOLKIT The following contains extracts of the research questions and suggested activities from each section of the toolkit. 150 The 1967 Referendum: A Western Australian Perspective Research Questions: What was the nexus question? Why do you think it did not succeed? Why do you think Western Australia recorded such a high ‘No’ vote compared to the other states? Do you think conditions for Aboriginal people have improved as a result of the 1967 Referendum? Why or why not? What do you think is the next step for Aboriginal Rights in Australia? What does the ‘Yes’ vote on the 1967 Referendum ballot paper mean to you? Why is there no reliable census data from before 1967? Activity: A large part of achieving a ‘Yes’ vote on the Referendum was the campaigning that gained community support. Make a poster, or come up with a campaign slogan to rally the community to vote ‘Yes’ on the 1967 Referendum, in favour of Aboriginal rights Compare and Contrast: Fremantle and Kalgoorlie Research Questions: Is a referendum on the same issues were to be held today, would you expect the result from your town to be any different? Why? Why not? What does Australia Day mean to you? Do you support Fremantle’s decision? Why or why not? If you were elected as the WA Premier, what possible solutions could you offer towards providing better services for Aboriginal people in Kalgoorlie? Activity: Stage a debate in your classroom arguing ‘for’ or ‘against’ moving the celebration date of Australia Day.