The Virtue of Truthfulness and the Military Profession: Reconciling Honesty with the Requirement to Deceive During War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Blitzkrieg: the Evolution of Modern Warfare and the Wehrmacht's

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 8-2021 Blitzkrieg: The Evolution of Modern Warfare and the Wehrmacht’s Impact on American Military Doctrine during the Cold War Era Briggs Evans East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Evans, Briggs, "Blitzkrieg: The Evolution of Modern Warfare and the Wehrmacht’s Impact on American Military Doctrine during the Cold War Era" (2021). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 3927. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/3927 This Thesis - unrestricted is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Blitzkrieg: The Evolution of Modern Warfare and the Wehrmacht’s Impact on American Military Doctrine during the Cold War Era ________________________ A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of History East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in History ______________________ by Briggs Evans August 2021 _____________________ Dr. Stephen Fritz, Chair Dr. Henry Antkiewicz Dr. Steve Nash Keywords: Blitzkrieg, doctrine, operational warfare, American military, Wehrmacht, Luftwaffe, World War II, Cold War, Soviet Union, Operation Desert Storm, AirLand Battle, Combined Arms Theory, mobile warfare, maneuver warfare. ABSTRACT Blitzkrieg: The Evolution of Modern Warfare and the Wehrmacht’s Impact on American Military Doctrine during the Cold War Era by Briggs Evans The evolution of United States military doctrine was heavily influenced by the Wehrmacht and their early Blitzkrieg campaigns during World War II. -

A.M.D.G. Catalogue of the College of the Sacred Heart(Title Page Missing)

5 Board of Trustees. Rev. J. M. MARRA, President. Rev. S. PERSONE, Vice-President. Rev. A. M. GENTILE, Rev. D. PANTANELLA, Rev. C. M. PINTO, Trustees. Rev. J. F. HOLLAND, Secretary. Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from LYRASIS Members and Sloan Foundation http://archive.org/details/amdgcatalogueof188990coll Faculty ar\d Officers. Rev. S. PERSONE, PRESIDENT. Rev. A. M. MANDALARI, PREFECT OF SCHOOLS AND DISCIPLINE, LIBRARIAN. Rev. G. LEZZI, CHAPLAIN. Rev. D. PANTANELLA, TREASURER, PREFECT OF HEALTH. Rev. FRANCIS X. KOWALD, ASSISTANT TREASURER. CLASSICAL COURSE. COLLEGIATE DEPARTMENT. Rev. D. PANTANELLA, PROFESSOR OF MENTAL AND MORAL PHILOSOPHY. Rev. A. M. MANDALARI, PROFESSOR OF EVIDENCES OF RELIGION. Rev. WILLIAM FORSTALL, PROFESSOR OF NATURAL PHILOSOPHY, HIGHER MATHEMATICS AND ASTRONOMY. Rev. FRANCIS X. GUBITOSI, PROFESSOR OF GEOLOGY AND MINERALOGY. Rev. HUGH L. MAGEVNEY, PROFESSOR OF RHETORIC AND ELOCUTION. Rev. RAPHAEL D'ORSI, PROFESSOR OF POETRY AND GEOMETRY. Rev. A. WILLIAM LONERGAN, PROFESSOR OF HUMANITIES. EMILE BIGGE, A. M., SPECIAL CLASS OF LATIN AND GREEK. vi. ACADEMIC DEPARTMENT. Rev. FRANCIS ROY, FIRST ACADEMIC, ALGEBRA. Rev. JOSEPH A. PHELAN, SECOND ACADEMIC, TRIGONOMETRY, PENMANSHIP. Rev. JOHN N. CORDOBA, THIRD ACADEMIC, PENMANSHIP. COMMERCIAL COURSE. Rev. M. IZAGUIRRE, FIRST AND SECOND COMMERCIAL, BOOK-KEEPING, FIRST ARITHMETIC. Rev. JOSEPH P. GONZALEZ, THIRD AND FOURTH COMMERCIAL, SECOND ARITHMETIC. Bro. PATRICK WALLACE, PREPARATORY. , OPTIONAL STUDIES. EMILE BIGGE, A. M., GERMAN. Rev. M. IZAGUIRRE, SPANISH. Rev. AUGUSTUS GIRARD, FRENCH. Rev. FRANCIS X. KOWALD, SHORT-HAND." Rev. M. IZAGUIRRE, TYPE-WRITING. Rev. FREDERICK BANKS, TELEGRAPHY. Rev. G. EEZZI, Rev. FRANCIS X. GUBITOSI, GEO. S. KEMPTON, PIANO. Rev. RAPHAEL D'ORSI, DRAWING. -

Simplicity Revisited

VINCENTIANA 6-2005 - FRANCESE November 24, 2005 − 1ª BOZZA ........................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... ...........................................................................................................................................................................................................................................TUDY ........................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... ........................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... ........................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... S........................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... Simplicity Revisited by Robert P. Maloney Superior General Everyone needs a guiding -

The Jesuits : Their Constitution and Teaching ; an Historical Sketch

" : ~~] I- Coforobm ZBrnbetsttp LIBRARY ESS && k&ttQaftj&m *& <\ szg/st This book is due two weeks from the last date stamped below, and if not returned or renewed at or before that time a fine of five cents a day will be incurred. THE JESUITS: THEIE CONSTITUTION AND TEACHING. %\\ pstorintl §>hk\, By W. C. CARTWRIGHT, M.P. LONDON: JOHN MUIUtAY, ALBEMARLE STKEET. 1876. The right oj Translation is reterved PRINTED BY WILLIAM CLOWES AND SONS, STAMFORD STREKT AND CHARIKG CROSS. TO EAWDON BROWN, Tl his Volume is Inscribed, IN GRATEFUL RECOLLECTION OF MUCH KINDNESS RECEIVED, AND OF MANY PLEASANT HOURS ENJOYED IN CASA DELLA VIDA, BY THE AUTHOR. 65645 a2 PREFACE. This Volume is in substance a republication of two articles, that appeared in No. 274 and No. 275 of the ' Quarterly Eeview,' with some additions and corrections. The additions are in the first section, which treats of the Constitution of the Society of Jesus. They consist of historical matter calculated to illustrate more amply this branch of the subject. The corrections are in both sections —the most important one, however, being in the second, which relates to points of Doctrine. In reference to these corrections the Author would say a few words of general explanation. On appearance in the 'Quarterly Eeview,' the articles were fortunate enough to attract the attention of a well-known Koman Catholic periodical, the 'Month.' They were subjected to incisive criticisms in a series of papers in its pages, which have been ascribed to a competent master of the matter. These have been issued in a reprint, prefaced by observations, complaining that no notice had been taken by the present writer of the strictures passed on his state- ments, and charging him, on ground of this silence, with want of candour. -

Manichaean Christians in Augustine's Life and Work Johannes Van Oort

1 Manichaean Christians in Augustine’s Life and Work Johannes van Oort Publishes in: Church History and Religious Culture 90.4 (2010) 505-546 www.brill.nl/chrc Abstract The article aims to give an overall overview of St Augustine’s attitude towards the Gnostic-Christian Manichaeans. First, a historical overview, mainly based on his Confessions, outlines Augustine’s acquaintance with the members of the Manichaean Church and his familiarity with their writings. Second, the place of the Manichaeans in a considerable number of Augustine’s other works is discussed. It is in particular in his many anti-Manichaean writings that the Church Father displays his intimate knowledge of the Manichaeans’ myth and their doctrines. Third, a summary is given of the research on the impact of the Manichaeans on Augustine. It is concluded that, from his early years onwards and to the very end of his life, the Manichaean Christians were a real and powerful force to him. Keywords Augustine of Hippo; Manichaeism; Patristics; Gnosticism; Roman Africa; history of Christian doctrine Document type Research article Affiliations 1. Professor of Patristics and Gnosticism, Radboud University, Nijmegen; 2. Visiting Professor of Patristics, University of Pretoria. Email: [email protected] 1. Introduction In Augustine’s life and work, the Manichaeans played a major role. They entered the course of his life when he was a young student of eighteen years, and their presence is perceptible even in his very final writings. Nearly all of his works deal with Manichaean questions, but in several of his books the Manichaeans and their doctrines are at the very centre of the discussion. -

Mental Reservation When Lying Is Permissible?

Mental Reservation When lying is permissible? Tuvya T. Amsel he pretest reached the question for- excessive body movement, sneaky and in- Tmulation phase. While discussing direct answers followed by an inaudible the comparison question the examinee, and unclear murmur continued all along a fresh graduate of a Jesuit Seminary of the comparison questions discussionI. It Theology, was asked: “Have you ever lied seemed like the examinee tries to over- in your life?”, “Never” came the answer come and fight his inner conflict in where with eye contact avoidance and hesita- in one hand he should tell the truth while tion. The examiner with somewhat teas- on the other hand to maintain a respect- ingly tone responded to that: “Never, ful and honest façade. The inner conflict ever, even not as a child?’. “Well… define itself was not exceptional; examiners face lie” came the answer with an inaudible it daily, but rather the avoidance patterns and unclear murmur. “What was that?” which were consistent and seemed like asked the examiner but the answer never came. The pattern of breaking eye con- I Seems like this examinee never read the large body of research rejecting those cues as being indicative tact along with physical uneasiness and of deception. The author is a private examiner in Israel, and a regular contributor to the publications of the American Polygraph Association. The views expressed in this column are solely those of the author, and do not necessarily represent those of the American Polygraph Association. Publishable comments and replies regarding this column can be sent to [email protected]. -

In Defense of the Falsiloquium

IN DEFENSE OF THE FALSILOQUIUM Scott M. Sullivan, Ph.D. University of St. Thomas MAY ONE TELL A LIE IN ORDER TO AVOID HARM to self or others, and yet still avoid sinning in the process? From the earliest history of philosophy, we see divergent opinions on this matter. Plato permitted the “noble lie” to bring about good,1 while Aristotle indicates telling untruth is always wrong.2 This divergence continues through the Church Fathers. Differences aside, all recognize the moral dilemma involved with maintaining a virtue of honesty while at the same time dealing appropriately with the classic, “What do you tell a Nazi at your door when he asks if there are any Jews in your cellar”? What we are seeking is if there is such a thing as a falsiloquium; that is to say, intentionally false speech that is not sinful. Does such a thing exist? The theological weight of Augustine and Aquinas dominates the answer in the Western Church, and that answer is “no”. This position is absolute, all speech that is contrary to one’s mind (contra mentem) is a lie, and lying is always a sin against truth, to which humans, being intellectual beings, are naturally suited. Thus, one may not tell a lie without sinning, even if to save another from injury. This is the ascendant teaching of the great majority of moralists in the West and not surprisingly is the prevailing position in manuals of moral theology and ethics. There is, though, another tradition which allows for some leniency on the matter. -

The Early Jesuit Mission to China 1580-1610

Kent Academic Repository Full text document (pdf) Citation for published version Frost, Duncan (2017) Misrepresentation, Manipulation, and Misunderstandings: The Early Jesuit Mission to China 1580-1610. Master of Arts by Research (MARes) thesis, University of Kent,. DOI Link to record in KAR https://kar.kent.ac.uk/64372/ Document Version UNSPECIFIED Copyright & reuse Content in the Kent Academic Repository is made available for research purposes. Unless otherwise stated all content is protected by copyright and in the absence of an open licence (eg Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher, author or other copyright holder. Versions of research The version in the Kent Academic Repository may differ from the final published version. Users are advised to check http://kar.kent.ac.uk for the status of the paper. Users should always cite the published version of record. Enquiries For any further enquiries regarding the licence status of this document, please contact: [email protected] If you believe this document infringes copyright then please contact the KAR admin team with the take-down information provided at http://kar.kent.ac.uk/contact.html University of Kent Misrepresentation, Manipulation, and Misunderstandings: The Early Jesuit Mission to China 1580-1610 By Duncan Frost Email: [email protected] Student Number: 16900752 Date of Submission: 03/08/17 Supervisor: Dr Jan Loop Word Count: 29,907 A Dissertation submitted to the School of History, University of Kent, in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Table of Contents Introduction 1 1: Presentation of the Self 13 2: Material Friendship 31 3: Images of the World 49 4: Hidden Knowledge 68 Conclusion 87 Appendix of Maps 94 Bibliography 110 Introduction Accommodation is the label frequently applied to Jesuit missionary policy in China.1 Probably the most famous Jesuit in the China mission, and a leader of the accommodation policy, was Matteo Ricci. -

Blitzkrieg Under Fire: German Rearmament, Total Economic Mobilization, and the Myth of the "Blitzkrieg Strategy:, 1933-1942

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies Legacy Theses 2000 Blitzkrieg under fire: German rearmament, total economic mobilization, and the myth of the "Blitzkrieg strategy:, 1933-1942 Gore, Brett Thomas Gore, B. T. (2000). Blitzkrieg under fire: German rearmament, total economic mobilization, and the myth of the "Blitzkrieg strategy:, 1933-1942 (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/21701 http://hdl.handle.net/1880/40717 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Blitzkrieg under Fire: Gennan Rearmament, Total Economic Mobilization, and the Myth of the "Blitzkrieg Strategy", 1933-1942 by Brett Thomas Gore A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTMI, FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY CALGARY, ALBERTA DECEMBER 2000 O Brett Thomas Gore 2000 National Library Biblioth&que nationale 1+1 of,,, du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographic Services services bibliographiques 395 WMinStreet 395. rue WeDingtm Ottawa ON KIA ON4 OttawaON KlAW Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclisive pennettant a la National Library of Canada to Bibliotheque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distri'bute or sell reproduire, pr;ter, distri'buer ou copies ofthis thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette these sous paper or electronic formats. -

Johann Peter Sommerville Current Position: Professor, University Of

1 CURRICULUM VITAE OF J.P.SOMMERVILLE Name: Johann Peter Sommerville Current position: Professor, University of Wisconsin, Madison (Assistant Professor 1988-90; Associate Professor 1990-3; Professor 1993-) Education: B.A. 1976, M.A. 1980, Ph.D. 1981; all from Cambridge University. Honors and awards: 2007: History Department, Karen F. Johnson Teaching Award 1998-9: R. Stanton Avery Distinguished Fellow, Huntington Library, San Marino, CA 1996-9: on Editorial Board of the Journal of Modern History 1995-7: Vilas Associate, UW-Madison 1993: Romnes Faculty Fellowship, University of Wisconsin- Madison. 1993 (January to June): NEH long-term Fellowship at the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington D.C. 1989-90: John M. Olin Faculty Fellow. 1986- : Fellow of the Royal Historical Society. 1980-4: Fellow, St John's College, Cambridge (includes membership of the History Faculty at Cambridge University). 1976-7: Joseph Hodges Choate Memorial Fellowship, Harvard University Publications: Books: Politics and ideology in England 1603-1640, Longman, London and New York 1986; paperback 1986; second impression 1989; third impression 1992; fourth impression 1995 (x+254pp). Thomas Hobbes: political ideas in historical context, London, Macmillan; New York, St Martin's Press 1992 (xiv+234pp; published simultaneously in hard and soft covers). (ed.) Sir Robert Filmer, Patriarcha and Other Writings, Cambridge University Press 1991 (in the series Cambridge Texts in the History of Political Thought; xlvi+327pp; published simultaneously in hard and soft covers). (ed.) King James VI and I, Political writings, Cambridge University Press 1994 (in the series Cambridge Texts in the History of Political Thought; xliv+329pp; published simultaneously in hard and soft covers). -

Univocation, Visibility and Reassurance in Post-Reformation Polemic

Perichoresis Volume 13. Issue 1 (2015): 55-72 DOI 10.1515/perc-2015-0004 EVIDENCE OF THINGS SEEN: UNIVOCATION, VISIBILITY AND REASSURANCE IN POST-REFORMATION POLEMIC JOSHUA RODDA * University of Nottingham ABSTRACT. This article reaches out to the audience for controversial religious writing after the English Reformation, by examining the shared language of attainable truth, of clarity and cer- tainty, to be found in Protestant and Catholic examples of the same. It argues that we must consider those aspects of religious controversy that lie simultaneously above and beneath its doc- trinal content: the logical forms in which it was framed, and the assumptions writers made about their audiences’ needs and responses. Building on the work of Susan Schreiner and others on the notion of certainty through the early Reformation, the article asks how English polemicists exalted and opened up that notion for their readers’ benefit, through proclamations of visibility, accessibility and honest dealing. Two case studies are chosen, in order to make a comparison across confessional lines: first, Protestant (and Catholic) reactions against the Jesuit doctrine of equivocation in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, which emphasized honesty and encouraged fear of hidden meaning; and second, Catholic opposition to the notion of an invisible —or relatively invisible —church. It is argued that the language deployed in opposition to these ideas displays a shared emphasis on the clear, certain, and reliable, and that which might be attained by human means. Projecting the emphases and assertions of these writers onto their audience, and locating it within a contemporary climate, the article thus questions the emphasis historians of religion place on the intangible —on faith —in considering the production and the reception of Reformation controversy. -

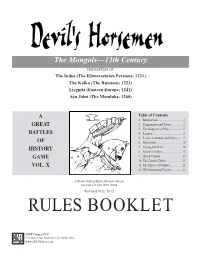

Rules Booklet

The Mongols—13th Century THE BATTLES OF: The Indus (The Khwarazmian Persians; 1221) The Kalka (The Russians; 1223) Liegnitz (Eastern Europe; 1241) Ayn Jalut (The Mamluks; 1260) A Table of Contents 1. Introduction .................................. 2 GREAT 2. Components and Terms ................ 2 3. The Sequence of Play ................... 5 BATTLES 4. Leaders ......................................... 5 5. Leader Activation and Orders ...... 7 OF 6. Movement ....................................10 7. Facing and ZOCs .........................14 HISTORY 8. Missile Combat ............................15 GAME 9. Shock Combat ..............................17 10. The Combat Tables ......................21 VOL. X 11. The Effects of Combat .................21 12. Withdrawal and Victory ...............23 a Richard Berg/Mark Herman design Version 1.0 AUGUST/2004 Revised July, 2012 RULES BOOKLET GMT Games, LLC P.O. Box 1308, Hanford, CA 93232-1308 www.GMTGames.com 2 Devil’s Horsemen — RULES OF PLAY about your units and how they act/interact, the better commander 1.0 Introduction you will be. The Devil’s Horsemen (TDH) simulates, in game form, four of the major battles the Mongols fought in the West to exert their supremacy For Those Who Have Played the System: TDH retains all the over the largest empire the world has ever known. TDH is the tenth core rules from the earlier titles, except for those marked with volume in the Great Battles of History Series. <<. A number of familiar rules have been dropped, reflecting the changes history and the March of Time have wrought. You will TDH uses the same “basic” system as Cataphract (Vol. VIII), includ- note the increased effectiveness of missile units due to the use of ing modifications from the “Attila” module, plus rule changes and the Composite Bow, so a thorough review of the Charts & Tables additions that portray the Mongol’s tactical concepts and advances in is heartily recommended.