Gender and Class Actions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Text Chat Contents

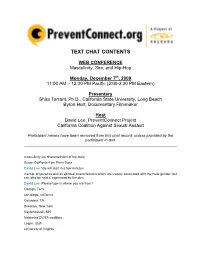

TEXT CHAT CONTENTS WEB CONFERENCE Masculinity, Sex, and Hip-Hop Monday, December 7th, 2009 11:00 AM – 12:30 PM Pacific (2:00-3:30 PM Eastern) Presenters Shira Tarrant, Ph.D., California State University, Long Beach Byron Hurt, Documentary Filmmaker Host David Lee, PreventConnect Project California Coalition Against Sexual Assault Participant names have been removed from this chat record, unless provided by the participant in text. masculinity are characteristics of the male Susan DelPonte from Penn State David Lee: We will start in a few minutes mental, physical as well as spiritual characteristics which are usually associated with the male gender, but can also be held & expressed by females David Lee: Please type in where you are from? Georgia Tech san diego, california Columbia, TN Brooklyn, New York Naytahwaush, MN Nebraska DV/SA coalition Logan, Utah University of Virginia Text Chat Contents Fargo, ND Virginia Beach, VA Humboldt County, CA Austin, TX Atlanta Georgia Spirit Lake, Iowa Humboldt and Del Norte Counties Fairfax Virginia Jennifer Thomas, Atlanta Georgia Twin Cities, MN Harrisonburg, VA Tampa, FL Durango, CO David Lee: And what organization are you with? Grand Forks, ND Fayetteville, Arkansas and Jacquie Marroquin from Haven Women's Center of Stanislaus Marsha Landrith: Lakeview, Oregon Norfolk, VA DOVE Program Human Services Inc Crisis Center of Tampa Bay Nancy Boyle: Rape & Abuse Crisis Center, Fargo ND Patti Torchia, Springfield, IL Rape and Abuse Crisis Center, Fargo, ND North Coast Rape Crisis Team, Humboldt/Del Norte CA Local health department CAPSA Domestic violence/rape advocacy organization United States Naval Academy, Annapolis, MD Patricia Maarhuis & Ginny Hauser: WSU Pullman WA GA Commission on Family Violence Sexual Assault Services Org. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Politics of Describing Pleasure: The Discursive Limits of Categorizing Feminist and Queer Pornography Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9p49913c Author Moll, Cooper Publication Date 2017 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles The Politics of Describing Pleasure: The Discursive Limits of Categorizing Feminist and Queer Pornography A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Master of Library and Information Science in Information Studies by Cooper Thorson Moll 2017 © Copyright by Cooper Thorson Moll 2017 ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS The Politics of Describing Pleasure: The Discursive Limits of Categorizing Feminist and Queer Pornography by Cooper Thorson Moll Master of Library and Information Science University of California Los Angeles, 2017 Professor Michelle L. Caswell, Chair This master’s thesis explores the stability and ramifications of two emergent categories of pornography: namely, feminist pornography and queer pornography. Though these terms— feminist and queer—have histories that connote resistance and disruption, they have been controlled and institutionalized in pornography to create a broader visibility and a deeper impact. These terms are analyzed in relation to two institutions that seek to control their meanings—the Feminist Porn Awards (FPAs) and PinkLabel.tv—and fourteen pornography studios that identify with either or both labels. I collected data from preexisting documents by implementing a content analysis. Two crucial findings suggest that 1) despite the foundational tenets of feminist and queer porn, as outlined by the FPAs and PinkLabel.tv, the studios did not always abide by them, and 2) strategic essentialism is a mode of temporarily fixing these categories to wield power in resistance to the naturalized mainstream power. -

WGST 1808 A: Introduction to Women’S and Gender Studies

Carleton University Fall 2018/Winter 2019 Pauline Jewett Institute of Women’s and Gender Studies WGST 1808 A: Introduction to Women’s and Gender Studies Thursday 2:35-4:25 Location: UC 231 Fall Term SA KM-TH Winter Term Instructor: Katharine Bausch Email: [email protected] Office: DT 1408 Phone: 613-520-2600 ext.8562 Office Hours: Thursday 12:00 pm – 2:00 pm Tutorial Leader Contacts: Course Description: This course provides an introduction to some of the major concepts, issues, and themes that inform the broad field of women’s and gender studies. Throughout the course we challenge many taken-for-granted assumptions about gender relations, feminism, and human inequalities. We examine the social, historical and cultural construction of “sex” and “gender” in relation to other social categories such as race, class, indigeneity, disability, and sexuality. We analyze gendered and racialized media representations of sexuality and beauty and consider how mainstream media messages are being resisted. This course also considers the challenges facing our world in North America and abroad. Through issues including violence, sexuality, health, poverty, and globalization, we explore diverse people’s experiences and think critically about the multiple pathways towards gender and economic justice for everyone. Course Objectives: 1. challenge dominant taken-for-granted assumptions about gender relations, feminism, and human inequalities 2. apply feminist and intersectional frameworks to their understanding of major Canadian and global social issues 3. identify ways in which gendered power relations are embedded in institutions and in everyday, social relations, practices, and values 4. recognize multiple forms of individual and collective resistance to social and economic inequalities in the past and present, and assess different visions and strategies for gender justice in local and global contexts 5. -

Introduction to Women's and Gender Studies

Carleton University Fall 2020/Winter 2021 Pauline Jewett Institute of Women’s and Gender Studies WGST 1808A: Introduction to Women and Gender Studies Location: Courses will be delivered ONLINE for the Fall 2020 term This course will be blended Instructor: Katharine Bausch Email: [email protected] Office: N/A Digital Office Hours: Mondays 12:00pm-2:00pm and Tuesdays 12:00pm-2:00pm • This outline is preliminary and subject to change • This course will be delivered as a blended course, meaning that most of the material will be asynchronous. Some material, however, such as tutorials, will be delivered at a specific time. Teaching Assistants: Course Description: This course provides an introduction to some of the major concepts, issues, and themes that inform the broad field of women’s and gender studies. Throughout the course, we challenge many taken-for-granted assumptions about gender relations, feminism, and human inequalities. We examine the social, historical and cultural construction of “sex” and “gender” in relation to other social categories such as race, class, indigeneity, disability, and sexuality. We analyze gendered and racialized media representations of sexuality and beauty and consider how mainstream media messages are being resisted. This course also considers the challenges facing our world in North America and abroad. Through issues including violence, sexuality, health, poverty, and globalization, we explore diverse people’s experiences and think critically about the multiple pathways towards justice for everyone. Course Objectives: 1. challenge dominant taken-for-granted assumptions about gender relations, feminism, and human inequalities 2. apply feminist and intersectional frameworks to their understanding of major Canadian and global social issues 3. -

Bad Gurley Feminism: the Myth of Post-War Domesticity

Journal of Feminist Scholarship Volume 16 Issue 16 Spring/Fall 2019 Article 3 Fall 2019 Bad Gurley Feminism: The Myth of Post-War Domesticity Erin Amann Holliday-Karre Qatar University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/jfs Part of the History of Gender Commons, Literature in English, North America Commons, Women's History Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Holliday-Karre, Erin A.. 2020. "Bad Gurley Feminism: The Myth of Post-War Domesticity." Journal of Feminist Scholarship 16 (Fall): 39-52. 10.23860/jfs.2019.16.03. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@URI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Feminist Scholarship by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@URI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Holliday-Karre: Bad Gurley Feminism: The Myth of Post-War Domesticity Bad Gurley Feminism: The Myth of Post-War Domesticity Erin Amann Holliday-Karre, Qatar University Abstract: According to feminist history, the 1950s constitute a lapse in feminist literature as women in the post-war era were ushered into the realm of domesticity. In this article I argue that this perceived literary “gap” was both created and perpetuated by feminist historians and scholars who insist that Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique (1963) was the defining feminist text of the time. I offer an alternative discourse to that of Friedan by presenting feminist writers who challenge, rather than adopt, masculine ideology as the means to women’s empowerment. -

The Girl Typing Discourse in North American Children's Television

The Girl Typing Discourse in North American Children’s Television Animation, 1990-2010 Emily Chandler A thesis in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of the Arts and Media Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences March 2017 Table of Contents Abstract 4 Acknowledgements 5 List of Figures 6 Introduction 7 Problem Identification 7 Aims 9 Scope of Inquiry and Rationale for Time Period, Medium and Topic 10 Theoretical Framework 13 Gap in Research 16 Sampling and Selection Procedures 17 Data Analysis Methods 22 Research Questions 23 Thesis Chapter Outline 24 Chapter One: Literature Review 25 Girl Typing 25 Female Representation in Animation 30 Postfeminist Discourses of Girlhood and Feminism 34 Girls as Empowered 34 Girls Out of Control 37 Neoliberal Feminism 41 Gap Identification 44 Conclusion 46 Chapter Two: Methodology and Methods 48 Introduction 48 Methodology 48 Data Analysis Methods 49 Discourse Analysis 50 Textual Analysis 51 Narrative Analysis 53 Limitations of Data Analysis Methods 55 Positionality 56 Sampling and Selection Procedures 58 Limitations of Sampling and Selection Procedures 59 Conclusion 60 Chapter Three: Agency and Power in As Told By Ginger 61 Introduction 61 As Told By Ginger (Nickelodeon, 2000-2004) 63 Everygirls 66 Popular Girls 70 Girl Typing and the Subverted Transformation 78 Episode Analysis: “Deja Who?” 81 2 Conclusion 89 Chapter Four: Androcentrism and Gender Entitlement in Recess 91 Introduction 91 Recess (Disney, 1997-2003) 91 Tomboys 98 Girly-Girls 104 Episode Analysis: “First -

Gender & Women's Studies Librarian

GENDER & WOMEN’S STUDIES LIBRARIAN NEW BOOKS ON WOMEN, GENDER, AND FEMINISM Numbers 68–69 Spring–Fall 2016 University of Wisconsin System NEW BOOKS ON WOMEN, GENDER, AND FEMINISM Nos. 68–69, Spring–Fall 2016 CONTENTS Scope ............................................................................ 1 Psychology and Psychoanalytic Theory ................ 35 Anthropology, Cultural Studies, and Ethnology ... 1 Reference ................................................................... 36 Architecture, Art, and Design .................................. 4 Religion ...................................................................... 36 Business and Work .................................................... 5 Science, Environment, Mathematics, and Technology ........................................................ 40 Economics .................................................................. 7 Sexuality ..................................................................... 41 Education .................................................................... 8 Sociology and Social Issues .................................... 42 Film and Television ................................................. 10 Families and Relationships ............................ 44 General Autobiography and Biography ............... 12 Violence against Women ............................... 46 Health, Medicine, and Biology ............................... 12 Sports, Hobbies, Recreation, and Travel .............. 47 History ......................................................................