Nuclear Terrorism: the Sum of All Fears Remarks Before the NPEC Fellowship Retreat—February 27, 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Syllabus: Office Hours: Mondays & Wednesdays 12:30 - 1:45Pm Or Tuesdays by Appt

“Now, I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.” -J. Robert Oppenheimer quoting from the Bhagavad-Gita at the 1st detonation of the atomic bomb “A world without nuclear weapons would be less stable and more dangerous for all of us.” -British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher” IAFS 4500-002/The Post-Cold War World: Global Security: Weapons of Mass Destruction Fall 2018 Instructor: Dr. Gregory D. Young Office: Ketchum Hall, Room 212 E-mail: [email protected] Lecture Times: Mondays, Wednesdays & Fridays, 11:00 – 11:50am in Hellums 104 Syllabus: http://spot.colorado.edu/~gyoung/home/4500/4500_syl.htm Office Hours: Mondays & Wednesdays 12:30 - 1:45pm or Tuesdays by appt. COURSE LINKS • Cold War Timeline • Schedule for Current Event Presentations • Schedule and Links to Course Reading Summaries • Research Paper Sign Up • Research Proposal Grade Sheet • In Class Debate Teams • In Class Debate Rules • In Class Debate Results • Link to Potential Midterm Questions • Midterm Grading Statistical Summary • Research Presentation Schedule • Oral Presentation Grade Sheet • Library Research Page • WMD Links • PowerPoint Links COURSE OBJECTIVES AND DESCRIPTION Twenty-six years have passed since the end of the Cold War, but we are still struggling to understand the nature of the world that has emerged in its wake. What are now the main sources of conflict in the “new world order”, now that the fifty-year bipolar standoff between the U.S. and the USSR has dissolved? Is terrorism of the kind exhibited on 9/11 the biggest threat to global security or is there a new, more sinister threat from weapons of mass destruction? This course is going to focus on the weapons of mass destruction that defined the “balance of terror during the Cold War. -

The Sum of All Fears: Israel's Perception of a Nuclear-Armed Iran

Ehud Eiran and Martin B. Malin The Sum of all Fears: Israel’s Perception of a Nuclear-Armed Iran Thucydides’ ancient logic still governs: uncertainty (over Iran’s nuclear intentions) and the fear this inspires (in Israel) increases the risk of another war (in the Middle East). Even if Israel’s response to the Iranian nuclear program does not lead the region into a war, Israel’s fears will be crucial in shaping Middle Eastern politics and will help to determine the stability of the region in the years ahead. The U.S. public has been hearing about Israeli fears of a nuclear Iran for several years. It is understandable if most Americans discount this drama as part of the background noise of international affairsÑa constant feature of international reporting in which the story remains the same, and the dire predictions never pan out. But it is important to pay attention to Israeli concerns about Iran for several reasons. First, Israel not only has a particular view of the threat posed by the military dimension of the Iranian nuclear program, it also has an independent means of taking action to alleviate its fears. Although Israel is less capable than the United States, if Israel were to launch strikes on Iran to set back the nuclear program, the effects would ripple across the region and beyond. Meir Dagan, former head of Israel’s external intelligence agency, the Mossad, warned a number of times that an Israeli attack on Iran would ‘‘ignite a regional war.’’1 Second, Israel’s anxieties over Iran could produce a series of defensive moves and escalating responses which spiral out of control in a manner that neither side Ehud Eiran is an Assistant Professor at the University of Haifa and an Affiliate of the Middle East Negotiation Initiative at the Program on Negotiation, Harvard Law School. -

The Effects of Math Anxiety on Math Achievement in Fifth Grade

The Sum of All Fears: The Effects of Math Anxiety assessed reached only partial mastery of math knowledge and skills fundamental for proficient work at the th4 grade level . In addition to the national implications from on Math Achievement in Fifth Grade Students and the results, there are also local implications as a comparison was made amongst the Implications for School Counselors the 50 states and the District of Columbia . The results indicated that 4th grade students from 33 other states scored higher in math literacy than 4th grade students Sarah E. Ruff and Dr. Susan R. Boes, The University of West Georgia in Georgia, students from 15 states scored lower and two states, Arkansas and New York, scored the same as Georgia students (NCES, 2012) . Despite the continued education reform and political efforts over the past decades, the math achievement Abstract gap has not closed . Numerous research studies have been conducted to pin-point the reasons for Low math achievement is a recurring weakness in many students . Math the gaps in mathematic achievement for American students . The causes are wide anxiety is a persistent and significant theme to math avoidance and low ranging. It is difficult to single out a particular cause for low achievement for achievement . Causes for math anxiety include social, cognitive, and American students, but a persistent theme is math anxiety . The negative effects of academic factors . Interventions to reduce math anxiety are limited as math anxiety on achievement are extensive . Geist (2010) suggests that for many they exclude the expert skills of professional school counselors to help children math achievement is not related to potential level but rather to their fear of and/or negative attitudes toward math . -

Nuclear Weapons and Critical Thinking

Preface: Nuclear Weapons and Critical Thinking This seminar on “Nuclear Weapons, Risk and Hope” addresses two basic questions: • How great is the risk that nuclear weapons will be used in anger? • How great is the hope of ending that threat? The following short story summarizes the answer to the first question, and lays a foundation for answering the second: Imagine that a man wearing a TNT vest were to come into the room and, before you could escape, managed to tell you that he wasn’t a suicide bomber and didn’t have the button to set off the explosives. Rather, there were two buttons in very safe hands. One was in Washington with President Obama and the other in Moscow with President Medvedev, so there was nothing to worry about. You’d still get out of that room as fast as you can! Just because we can’t see the nuclear weapons controlled by those two buttons, why have we stayed here for over 50 years, complacently assuming that because Earth’s explosive vest hasn’t yet gone off, it never will? As if confronted by that man, we need to be plotting a rapid escape. Thinking about sitting next to that man wearing the TNT vest brings the risk into clear focus, especially when it is remembered that buttons also are present in London, Paris, Beijing, New Delhi, Islamabad, Jerusalem, and Pyongyang – and terrorists are trying to get a button of their own. This story also helps illuminate the hope: Right now, society complacently assumes that the risk posed by nuclear weapons evaporated with the end of the Cold War. -

The Sum of All FEARS Investor Sentiment and Asset Prices

RFS Advance Access published November 13, 2014 The Sum of All FEARS Investor Sentiment and Asset Prices Zhi Da Mendoza College of Business, University of Notre Dame Joseph Engelberg Rady School of Management, University of California at San Diego Downloaded from Pengjie Gao Mendoza College of Business, University of Notre Dame We use daily Internet search volume from millions of households to reveal market-level http://rfs.oxfordjournals.org/ sentiment. By aggregating the volume of queries related to household concerns (e.g., “recession,” “unemployment,” and “bankruptcy”), we construct a Financial and Economic Attitudes Revealed by Search (FEARS) index as a new measure of investor sentiment. Between 2004 and 2011, we find FEARS (i) predict short-term return reversals, (ii) predict temporary increases in volatility, and (iii) predict mutual fund flows out of equity funds and into bond funds. Taken together, the results are broadly consistent with theories of investor sentiment. (JEL G10) at University of Notre Dame on November 18, 2014 John Maynard Keynes (1936) argued that markets can fluctuate wildly under the influence of investors’ “animal spirits,” which move prices in a way unrelated to fundamentals. Fifty years later, De Long, Shleifer, Summers, and Waldmann (1990; DSSW hereafter) formalized the role of investor sentiment in financial markets. DSSW demonstrate that if uninformed noise traders base their trading decisions on sentiment and risk-averse arbitrageurs encounter limits to arbitrage, sentiment changes will lead to more noise -

A Historian Reflects on America's Half-Century Encounter With

THE VIEW FROM THE NINETIES ast-forward a full decade. By fiction to movies, video games, the mid-1990s, the Cold War and television programs. Further, Fwas fading into memory, and Americans continued to wrestle the "nuclear threat" had mutated with the meaning of the primal from its classic form—a nightmar event that had started it all, the ish, world-destroying holocaust— atomic destruction of two cities by into a series of still-menacing but the order of a U.S. president in Au less cosmic regional dangers and gust 1945- The fiftieth anniversary technical issues. of the end of World War II, and of But these developments, wel the nearly simultaneous Hiroshima come as they were, did not mean and Nagasaki bombings, raised that the historical realities ad this still contentious issue in a par dressed in this book had suddenly ticularly urgent form, inviting re vanished. For one thing, nuclear flections on America's half-century menace in forms both fanciful and effort to accommodate nuclear serious remained very much alive weapons into its strategic thinking, in the mass culture, from popular its ethics, and its culture. 197 1 4 NUCLEAR MENACE IN THE MASS CULTURE OF THE LATE COLD WA R ERA AN D BEYOND Paul Boyer and Eric Idsvoog v espite the end of the Cold War, the waning of the nu clear arms race, and the disappearance of "global Dthermonuclear war" from pollsters' lists of Ameri cans' greatest worries, U.S. mass culture of the late 1980s and the 1990s was saturated by nuclear themes. -

An Alliance Against Nuclear Terrorism Graham Allison and Andrei Kokoshin

Chapter 1 The New Containment: An Alliance Against Nuclear Terrorism Graham Allison and Andrei Kokoshin During the Cold War, American and Russian policymakers and citizens thought long and hard about the possibility of nuclear attacks on their respective homelands. But with the fall of the Berlin Wall and the disap- pearance of the Soviet Union, the fears of a nuclear conºict faded from most minds. This is ironic and potentially tragic, since the threat of a nuclear attack on the United States or Russia is certainly greater today than it was in 1989. In the aftermath of Osama bin Laden’s September 11, 2001, assault, which awakened the world, especially Americans, to the reality of global terrorism, it is incumbent upon national security analysts everywhere to think again about the unthinkable. Could a nuclear terrorist assault hap- pen today? Our considered answer is: yes, unquestionably, without any doubt. It is not only a possibility but, in fact, the most urgent unad- dressed national security threat to both the United States and Russia.1 Consider this hypothetical: a crude nuclear weapon constructed from This article is reprinted with permission from The National Interest. It appeared as: Graham Allison and Andrei Kokoshin, “The New Containment: An Alliance Against Nuclear Ter- rorism,” The National Interest, Vol. 69 (Fall 2002), pp. 35–45. 1. This judgment echoes the major ªnding of a Department of Energy Task Force on nonproliferation programs with Russia led by Howard Baker and Lloyd Cutler: “The most urgent unmet national security threat to the United States today is the danger that weapons of mass destruction or weapons-usable material in Russia could be sto- len and sold to terrorists or hostile nation states and used against American troops abroad or citizens at home.” A Report Card on the Department of Energy’s Nonproliferation Programs with Russia, January 10, 2001.<http://www.hr.doe.gov/seab/rusrpt. -

Fyse Final Draft

Understanding Loyalty, Trust, and Deception Through an Analysis of Jack Ryan in Tom Clancy’s The Hunt for Red October and Its 1990 Film Adaptation Rachel Collins FYSE Espionage in Film and Fiction 13 December 2014 !1 In his debut 1984 novel The Hunt for Red October, Tom Clancy introduces the character of Jack Ryan as a CIA analyst and protagonist that classically upholds the fictional spy agent’s values of trust and loyalty, as defined by Alan Wolfe in his article “On Loyalty.” Ryan, not an agent, but rather an analyst for the CIA, is thrown into the world of spies and proves his capability through his balanced loyalties, intelligent trust, and straightforward actions. This thrilling character was easily transformed into an unforgettable hero both through Clancy’s novel and its 1990 film adaptation. In both the novel and film, through constant internal and external conflicts concerning trust and loyalty, Jack Ryan expresses the needlessness of deception and what it means to be a spy in a fictional story. To further examine Jack Ryan as a fictional spy character, the definition of loyalty must first be explored so it can be applied to him as a CIA agent. For this, Alan Wolfe, political scientist and sociologist on the faculty of Boston College, in his article “On Loyalty” successfully outlines a thorough definition of the concept of loyalty that will be used throughout this paper. Wolfe argues, “Loyalty is an important virtue because honoring it establishes that there is something in the world more important than our immediate instincts and desires” (48). -

Amazon Greenlights 10-Episode Season of Tom Clancy's Jack Ryan

Amazon Greenlights 10-Episode Season of Tom Clancy’s Jack Ryan, Exclusively for Amazon Prime Video August 16, 2016 New Amazon Original series is slated to star John Krasinski Set to be co-produced by Paramount and Skydance Television and executive produced by Carlton Cuse, Graham Roland, Michael Bay, Brad Fuller, Andrew Form, David Ellison, Dana Goldberg, Marcy Ross, Mace Neufeld and Lindsey Springer In addition to unlimited video streaming on Prime Video, Amazon Prime members enjoy unlimited One-Day Delivery on millions of items, more than a million songs available to stream and download through Prime Music, unlimited photo storage in Amazon Cloud Drive, access to a million Kindle books to borrow, and early access to select Lightning Deals on www.amazon.co.uk — all available for a monthly membership of £7.99/month, or a best value annual membership of just £79/year. New customers can enjoy a free 30-day trial of Amazon Prime today by visiting www.amazon.co.uk/primevideo. LONDON—August 16, 2016—Amazon today announced it has greenlitTom Clancy’s Jack Ryan from Paramount and Skydance Television, to debut on Amazon Prime Video. The one-hour, 10-episode dramatic series is slated to star John Krasinski (13 Hours, The Office) as Jack Ryan and is projected to shoot in the US, Europe and Africa. Jack Ryan is a reinvention with a modern sensibility of the famed and lauded Tom Clancy hero, a character with a star-filled Hollywood history, having been previously portrayed by Alec Baldwin, Harrison Ford, Ben Affleck and Chris Pine. -

Students Address Conflict

TUESEDAY, MAY 14, 2002 WWW.THESPARTANDAILY.COM AVALANCE RUMBLES Colorado pulls 2-1 overtime victory in San Jose. Sports, 8 :e ir TAN ''THE SUM OF ALL FEARS" a- Ben Affleck stars in Tom Clancy is adaptation o I ot 8 Arts & Entertaiment, 5 k- y- ,No. 71 V ALSO IN TODAY'S ISSUE ol Opinion 2-3 Sparta Guide 2 Classified 7 ly IL Sports 8 Crossword 7 A & E 4-5 p- SERVINXN lic TOSE STATE UNIVERSITY SINCE 1934 9: es 5.2 quake ee Students address at conflict ng shakes the 3 South Bay on GILROY, Calif (AP) - A substantial earthquake a shook the San Francisco Bay area Monday night, iic rattling the upper decks of the Compaq Center for about 10 seconds as a sellout crowd watched the ck third period of a National Hockey League playoff game. There were no reports of injuries or significant damage from the quake, which struck at 10 p.m. with a preliminary magnitude of 5.2. It was cen- tered 3 miles southwest of Gilroy, outside San Jose, according to the U.S. Geological Service. Of several aftershocks, the largest was a 2.5. See QUAKE. Page 6 SJSU reacts to tremor By Ben Aguirre Jr. D MIN E\ft MI EI)II(ilt A 5.2-magnitude earthquake rocked San Jose State University and surrounding cities Monday shortly after 10 p.m. According to the University Police Department, no injuries or damages were reported on campus as of 10:42 p.m. Shortly after the quake, some students on the first floor of Clark Library remained sitting at their computer terminals, while others from the upper floors left the building. -

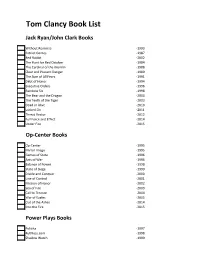

Tom Clancy Book List

Tom Clancy Book List Jack Ryan/John Clark Books Without Remorse -1993 Patriot Games -1987 Red Rabbit -2002 The Hunt for Red October -1984 The Cardinal of the Kremlin -1988 Clear and Present Danger -1989 The Sum of All Fears -1991 Debt of Honor -1994 Executive Orders -1996 Rainbow Six -1998 The Bear and the Dragon -2000 The Teeth of the Tiger -2003 Dead or Alive -2010 Locked On -2011 Threat Vector -2012 Full Force and Effect -2014 Under Fire -2015 Op-Center Books Op-Center -1995 Mirror Image -1995 Games of State -1996 Acts of War -1996 Balance of Power -1998 State of Siege -1999 Divide and Conquer -2000 Line of Control -2001 Mission of Honor -2002 Sea of Fire -2003 Call to Treason -2004 War of Eagles -2005 Out of the Ashes -2014 Into the Fire -2015 Power Plays Books Politika -1997 Ruthless.com -1998 Shadow Watch -1999 Bio-Strike -2000 Cold War -2001 Cutting Edge -2002 Zero Hour -2003 Wild Card -2004 Net Force Books Net Force -1999 Hidden Agendas -1999 Night Moves -1999 Breaking Point -2000 Point of Impact -2001 CyberNation -2001 State of War -2003 Changing of the Guard -2003 Springboard -2005 The Archimedes Effect -2006 Net Force Explorers Books Virtual Vandals -1998 The Deadliest Game -1998 One is the Loneliest Number -1999 The Ultimate Escape -1999 The Great Race -1999 End Game -1998 Cyberspy -1999 Shadow of Honor -2000 Private Lives -2000 Safe House -2000 Gameprey -2000 Duel Identity -2000 Deathworld -2000 High Wire -2001 Cold Case -2001 Runaways -2001 Splinter Cell Books Splinter Cell -2004 Operation Barracuda -2005 Checkmate -2006 Fallout -2007 Conviction -2009 Endgame -2009 Blacklist Aftermath -2013 Ghost Recon Books Ghost Recon -2008 Combat Ops -2011 EndWar Books EndWar -2008 The Hunted -2011 H.A.W.X. -

The Sum of All Fears

The Sum of All Fears Allen Moon 10/01/07 The Sum of All Fears stars Ben Affleck as Jack Ryan, Morgan Freeman as William Cabbot, James Cromwell as President Fowler, and Ciaran Hinds as President Nemerov. Ben Affleck delivers an acceptable performance as Jack Ryan, a C.I.A. analyst who gets wrapped up in an international crisis between the United States and Russia. Morgan Freeman plays the Director of the C.I.A. and, as always, plays his role well. James Cromwell plays the President of the United States. Cromwell plays the president as a stern man who is determined to present the United States as a strong super power. Cromwell’s Russian counter part is played by Ciaran Hinds, who plays the Russian President quite well. Hinds exudes the cold, stern persona of a stereotypical Russian higher-up quite well. Overall, the acting in The Sum of All Fears is quite pleasant. The Sum of All Fears is developed in a piecemeal fashion as several plot lines are explored. The formula is not new, but works successfully to keep the viewer interested. The movie opens with the crash of an Israeli jet in 1973. The jet was carrying a nuclear bomb that is lost in the sands of the Golan in S y r i a . Twenty-nine years pass, and the bomb is randomly discovered by a couple of local men. They are not quite sure what they have found, but know that someone may want to buy it. Meanwhile, Ryan and Cabbot are sent to Russia to inspect a nuclear decommission facility.