Lake Washington Ship Canal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ballard/Fremont Neighborhood Greenways

Ballard-Interbay Regional Transportation System Seattle Bicycle Advisory Board SDOT Policy & Planning Department of Transportation May 6, 2020 Presentation overview •Project background and purpose •Project scope, outcomes, schedule •Engagement/equity •Overview of comments •Questions for SBAB Department of Transportation 3 www.seattle.gov/transportation/birt Department of Transportation 2019 Washington State legislative language ESHB 1160 – Section 311(18)(b) “Funding in this subsection is provided solely The plan must examine replacement of the Ballard for the city of Seattle to develop a plan and Bridge and the Magnolia Bridge, which was damaged in report for the Ballard-Interbay Regional the 2001 Nisqually earthquake. The city must provide a Transportation System project to improve report on the plan that includes recommendations to the mobility for people and freight. The plan Seattle city council, King county council, and the must be developed in coordination and transportation committees of the legislature by partnership with entities including but not November 1, 2020. The report must include limited to the city of Seattle, King county, the recommendations on how to maintain the current and Port of Seattle, Sound Transit, the future capacities of the Magnolia and Ballard bridges, an Washington state military department for the overview and analysis of all plans between 2010 and Seattle armory, and the Washington State 2020 that examine how to replace the Magnolia bridge, Department of Transportation. and recommendations on a timeline -

Vol. 82 Tuesday, No. 33 February 21, 2017 Pages 11131–11298

Vol. 82 Tuesday, No. 33 February 21, 2017 Pages 11131–11298 OFFICE OF THE FEDERAL REGISTER VerDate Sep 11 2014 18:37 Feb 17, 2017 Jkt 241001 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 4710 Sfmt 4710 E:\FR\FM\21FEWS.LOC 21FEWS sradovich on DSK3GMQ082PROD with FRONT MATTER WS II Federal Register / Vol. 82, No. 33 / Tuesday, February 21, 2017 The FEDERAL REGISTER (ISSN 0097–6326) is published daily, SUBSCRIPTIONS AND COPIES Monday through Friday, except official holidays, by the Office PUBLIC of the Federal Register, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC 20408, under the Federal Register Subscriptions: Act (44 U.S.C. Ch. 15) and the regulations of the Administrative Paper or fiche 202–512–1800 Committee of the Federal Register (1 CFR Ch. I). The Assistance with public subscriptions 202–512–1806 Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Publishing Office, Washington, DC 20402 is the exclusive distributor of the official General online information 202–512–1530; 1–888–293–6498 edition. Periodicals postage is paid at Washington, DC. Single copies/back copies: The FEDERAL REGISTER provides a uniform system for making Paper or fiche 202–512–1800 available to the public regulations and legal notices issued by Assistance with public single copies 1–866–512–1800 Federal agencies. These include Presidential proclamations and (Toll-Free) Executive Orders, Federal agency documents having general FEDERAL AGENCIES applicability and legal effect, documents required to be published Subscriptions: by act of Congress, and other Federal agency documents of public interest. Assistance with Federal agency subscriptions: Documents are on file for public inspection in the Office of the Email [email protected] Federal Register the day before they are published, unless the Phone 202–741–6000 issuing agency requests earlier filing. -

AWO Letter of Support for Salmon Bay Bridge

755 Winslow Way East Charles P. Costanzo Suite 105B General Counsel & Vice President – Pacific Region Bainbridge Island, WA 98110 PHONE: 203.980.3051 EMAIL: [email protected] March 15, 2021 The Honorable Pete Buttigieg Secretary U.S. Department of Transportation 1200 New Jersey Ave SE Washington, DC 20590 Dear Secretary Buttigieg, On behalf of The American Waterways Operators (AWO), I am pleased to express our support for the Washington Department of Transportation’s application for 2021 INFRA federal discretionary grant funding for the Salmon Bay Bridge Rehabilitation Project. The U.S. tugboat, towboat, and barge industry is a vital segment of America’s transportation system. The industry safely and efficiently moves more than 760 million tons of cargo each year, including more than 60 percent of U.S. export grain, energy sources, and other bulk commodities that are the building blocks of the U.S. economy. The fleet consists of nearly 5,500 tugboats and towboats and over 31,000 barges. These vessels transit 25,000 miles of inland and intracoastal waterways; the Great Lakes; and the Atlantic, Pacific, and Gulf coasts. Tugboats also provide essential services including ship docking, tanker escort, and bunkering in ports and harbors around the country. Built in the early 1900s, the Salmon Bay Bridge is a vital piece of the multimodal network in the Pacific Northwest. It is a double-track lift bridge that supports multimodal transportation for BNSF freight rail, Amtrak intercity passenger trains, and Sound Transit Sounder North commuter rail service. The Salmon Bay Bridge Rehabilitation Project will return the structure to a state of good repair by replacing the lift bridge counterweight and pivot mechanism components, extending its lifespan another 50 years. -

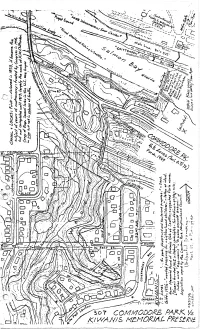

Commodore Park Assumes Its Name from the Street Upon Which It Fronts

\\\\. M !> \v ri^SS«HV '/A*.' ----^-:^-"v *//-£ ^^,_ «•*_' 1 ^ ^ : •'.--" - ^ O.-^c, Ai.'-' '"^^52-(' - £>•». ' f~***t v~ at, •/ ^^si:-ty .' /A,,M /• t» /l»*^ »• V^^S^ *" *9/KK\^^*j»^W^^J ** .^/ ii, « AfQVS'.#'ae v>3 ^ -XU ^4f^ V^, •^txO^ ^^ V ' l •£<£ €^_ w -* «»K^ . C ."t, H 2 Js * -^ToT COMMODOR& P V. KIWAN/S MEMORIAL ru-i «.,- HISTORY: PARK When "Indian Charlie" made his summer home on the site now occupied by the Locks there ran a quiet stream from "Tenus Chuck" (Lake Union) into "Cilcole" Bay (Salmon Bay and Shilshole Bay). Salmon Bay was a tidal flat but the fishing was good, as the Denny brothers and Wil- liam Bell discovered in 1852, so they named it Salmon Bay. In 1876 Die S. Shillestad bought land on the south side of Salmon Bay and later built his house there. George B. McClellan (famed as a Union General in the Civil War) was a Captain of Engineers in 1853 when he recommended that a canal be dug from Lake Washington to Puget Sound, a con- cept endorsed by Thomas Mercer in an Independence Day celebration address the following year which he described as a union of lakes and bays; and so named Lake Union and Union Bay. Then began a series of verbal battles that raged for some 60 years from here to Washington, D.C.! Six different channel routes were not only proposed but some work was begun on several. In §1860 Harvey L. Pike took pick and shovel and began digging a ditch between Union Bay and Lake i: Union, but he soon tired and quit. -

Analysis of Existing Data on Lake Union/Ship Canal

Water Quality Assessment and Monitoring Study: Analysis of Existing Data on Lake Union/Ship Canal October 2017 Alternative Formats Available Water Quality Assessment and Monitoring Study: Analysis of Existing Data on Lake Union/Ship Canal Prepared for: King County Department of Natural Resources and Parks Wastewater Treatment Division Submitted by: Timothy Clark, Wendy Eash-Loucks, and Dean Wilson King County Water and Land Resources Division Department of Natural Resources and Parks Water Quality Assessment and Monitoring Study: Analysis of Existing Data on Lake Union/Ship Canal Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank for following people for their contributions to this report: Staff at the King County Environmental Laboratory for field and analytical support. Dawn Duddleson (King County) for her help in completing the literature review. The King County Water Quality and Quantity Group for their insights, especially Sally Abella for her thorough and thoughtful review. Lauran Warner, Frederick Goetz, and Kent Easthouse of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Judy Pickar (project manager), Dean Wilson (science lead), and King County project team members (Bob Bernhard, Mark Buscher, Timothy Clark, Betsy Cooper, Wendy Eash‐Loucks, Elizabeth Gaskill, Martin Grassley, Erica Jacobs, Susan Kaufman‐Una, Lester, Deborah, Kate Macneale, Chris Magan, Bruce Nairn, Sarah Ogier, Erika Peterson, John Phillips, Cathie Scott, Jim Simmonds, Jeff Stern, Dave White, Mary Wohleb, and Olivia Wright). The project’s Science and Technical Review Team members—Virgil Adderley, Mike Brett, Jay Davis, Ken Schiff, and John Stark—for guidance and review of this report. Citation King County. 2017. Water Quality Assessment and Monitoring Study: Analysis of Existing Data on Lake Union/Ship Canal. -

Montlake Cut Tunnel Expert Review Panel Report

SR 520 Project Montlake Cut Tunnel Expert Review Panel Report EXPERT REVIEW PANEL MEMBERS: John Reilly, P.E., C.P.Eng. John Reilly Associates International Brenda Böhlke, Ph.D., P.G.. Myers Böhlke Enterprise Vojtech Gall, Ph.D., P.E. Gall Zeidler Consultants Lars Christian Ingerslev, P.E. PB Red Robinson, C.E.G., R.G. Shannon and Wilson Gregg Korbin, Ph.D. Geotechnical Consultant John Townsend, C.Eng. Hatch-Mott MacDonald José Carrasquero-Verde, Principal Scientist Herrera Environmental Consultants Submitted to the Washington State Department of Transportation July 17, 2008 SR520, Montlake Cut, Tunnel Alternatives, Expert Review Panel Report July 17h, 2008 Page 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY......................................................................................................................5 1.1. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................................5 1.2. ENVIRONMENTAL CONSIDERATIONS ......................................................................................................5 1.3. TUNNELING METHODS CONSIDERED......................................................................................................5 Figure 1 - Immersed Tunnel Construction (General) ......................................................................................6 Figure 2 - Tunnel Boring Machine (Elbe River, Hamburg) ............................................................................6 Figure 3 – Sequential Excavation -

Oregon's Civil

STACEY L. SMITH Oregon’s Civil War The Troubled Legacy of Emancipation in the Pacific Northwest WHERE DOES OREGON fit into the history of the U.S. Civil War? This is the question I struggled to answer as project historian for the Oregon Historical Society’s new exhibit — 2 Years, Month: Lincoln’s Legacy. The exhibit, which opened on April 2, 2014, brings together rare documents and artifacts from the Mark Family Collection, the Shapell Manuscript Founda- tion, and the collections of the Oregon Historical Society (OHS). Starting with Lincoln’s enactment of the final Emancipation Proclamation on January , 863, and ending with the U.S. House of Representatives’ approval of the Thirteenth Amendment abolishing slavery on January 3, 86, the exhibit recreates twenty-five critical months in the lives of Abraham Lincoln and the American nation. From the moment we began crafting the exhibit in the fall of 203, OHS Museum Director Brian J. Carter and I decided to highlight two intertwined themes: Lincoln’s controversial decision to emancipate southern slaves, and the efforts of African Americans (free and enslaved) to achieve freedom, equality, and justice. As we constructed an exhibit focused on the national crisis over slavery and African Americans’ freedom struggle, we also strove to stay true to OHS’s mission to preserve and interpret Oregon’s his- tory. Our challenge was to make Lincoln’s presidency, the abolition of slavery, and African Americans’ quest for citizenship rights relevant to Oregon and, in turn, to explore Oregon’s role in these cataclysmic national processes. This was at first a perplexing task. -

Building a Better Fish Trap

BUILDING A BETTER FISH TRAP CORY CUTHBERTSON, WDFW History of L.Washington sockeye and water projects Broodstock collection at the old trap and weir at Cavanaugh Ponds Fall 2008 installation and operation of the new floating resistance board weir in Renton, WA What we learned in the first year and how we can improve next year Ballard Locks Interim Sockeye Hatchery • Established 1991 • 17 million fry capacity • Operated by Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife Long Term Project Goals Increase returns of Cedar R sockeye and provide fishing opportunity for public and tribes Avoid or reduce effects on naturally spawning populations Challenges Broodstock collection ESA listed Chinook Temporary structure in a volatile river Weir at Cavanaugh Pond 11/6/2006 Why a New Weir in Renton? About a 1/3 of the sockeye spawn below Cavanaugh Pond, limiting broodstock collection. The new weir is a resistance board weir, which will be able to withstand higher flows. Doesn’t require equipment for installation/removal. Weir Panel Nomenclature Results: A better fish trap? ~Same # of eggs from ½ the # of adults into the L. Washington basin Installed in 2 days, removed in 4 hours without any heavy equipment Next year we should… Better trap door to target Chinook passage New Hatchery Thanks! Paul Faulds and Gary Sprague, SPU Brodie Antipa, WDFW Seattle Public Utilities Cramer Fish Sciences Questions ? What’s the Hurry? The Lake Washington fish flop of 2008 Age Composition Of Females 100 80 60 Hatch 40 NOR 20 0 % Of Sampled Fish % Of Sampled 3-yr 4-yr 5-yr Age At Maturati on Age Composition In Hatchery & Wild Females Is Comparable Sockeye introductions and propagation in Lake Washington From Cultus Lake 1917 1935 1944 23,655 to North Cr. -

8 Chittenden Locks 47

Seattle’s Aquatic Environments: Hiram M. Chittenden Locks Hiram M. Chittenden Locks The following write-up relies heavily on the Hiram M. Chittenden Locks/Salmon Bay Subarea Chapter by Fred Goetz in the Draft Reconnaissance Assessment – Habitat Factors that Contribute to the Decline of Salmonids by the Greater Lake Washington Technical Committee (2001). Overview The Hiram M. Chittenden Locks (Locks) were Operation of the navigational locks involves constructed by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers raising or lowering the water level within either (the Corps) in 1916 and commissioned in 1917. the large or small lock chamber so that vessels may The Locks were built as a navigation project to pass between the two waterbodies. The filling and allow boats to travel from the marine waters of emptying of the large lock chamber is achieved by Puget Sound to the protected freshwaters of Lake use of a system of two large conduits that can Union and Lake Washington. The Locks are either fill the entire lock or half of the lock. This comprised of two navigational lock chambers: a is achieved by using a miter gate that divides the large lock that accommodates both large and small large lock chamber into two sections. Water is vessels and a small lock used by smaller vessels. In taken into the conduits via two culvert intakes addition to the lock chambers, the Locks include a located immediately upstream of the structure. dam, 6 spillway bays, and a fish ladder. Water is conveyed through each conduit and is The Locks form a dam at the outlet of the Lake discharged into the lock chamber through outlet Washington and Lake Union/Ship Canal system culverts on each side of the chamber. -

Coast Salish Culture – 70 Min

Lesson 2: The Big Picture: Coast Salish Culture – 70 min. Short Description: By analyzing and comparing maps and photographs from the Renton History Museum’s collection and other sources, students will gain a better understanding of Coast Salish daily life through mini lessons. These activities will include information on both life during the time of first contact with White explorers and settlers and current cultural traditions. Supported Standards: ● 3rd Grade Social Studies ○ 3.1.1 Understands and applies how maps and globes are used to display the regions of North America in the past and present. ○ 3.2.2 Understands the cultural universals of place, time, family life, economics, communication, arts, recreation, food, clothing, shelter, transportation, government, and education. ○ 4.2.2 Understands how contributions made by various cultural groups have shaped the history of the community and the world. Learning Objectives -- Students will be able to: ● Inspect maps to understand where Native Americans lived at the time of contact in Washington State. ● Describe elements of traditional daily life of Coast Salish peoples; including food, shelter, and transportation. ● Categorize similarities and differences between Coast Salish pre-contact culture and modern Coast Salish culture. Time: 70 min. Materials: ● Laminated and bound set of Photo Set 2 Warm-Up 15 min.: Ask students to get out a piece of paper and fold it into thirds. 5 min.: In the top third, ask them to write: What do you already know about Native Americans (from the artifacts you looked at in the last lesson)? Give them 5 min to brainstorm. 5 min.: In the middle, ask them to write: What do you still want to know? Give them 5min to brainstorm answers to this. -

Press Release Locks TAST Final 8-26-20

New device may keep seals away from the Ballard Locks, giving migrating salmon a better chance at survival For Immediate Release: 8/26/20 - Seattle, WA SUMMARY A group of partners working to improve salmon stocks have deployed a newly developed device on the west side of the Ballard Locks that uses underwater sound to keep harbor seals away from this salmon migration bottleneck. If effective, the device may help salmon populations in jeopardy by reducing predation without harming marine mammals. STORY The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and Oceans Initiative, with support from Long Live the Kings, University of St Andrews, Genuswave, Puget Sound Partnership, Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, Muckleshoot Indian Tribe, and other partner organizations have deployed a Targeted Acoustic Startle Technology (TAST) on the west side of the Ballard (Hiram M. Chittenden) Locks. The TAST is intended to keep harbor seals away from the fish ladder allowing salmon to reach the Lake Washington Ship Canal from Puget Sound. Seals and sea lions are known to linger at this migration bottleneck and consume large numbers of salmon returning to the spawning grounds. If successful, the device may help recover dwindling salmon runs, without harming marine mammals. "We are always looking for new innovations to help the environment,” said USACE spokesperson Dallas Edwards. “We are excited to see the results of this study." Every salmon and steelhead originating from the Sammamish or Cedar river must pass through the Ballard Locks twice during its life, once as a young smolt and again as an adult. With limited routes to get through the locks, salmon are funneled through a small area. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Categorization in Motion: Duwamish Identity, 1792-1934 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/75s2k9tm Author O'Malley, Corey Susan Publication Date 2017 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Categorization in Motion: Duwamish Identity, 1792-1934 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology by Corey Susan O’Malley 2017 © Copyright by Corey Susan O’Malley 2017 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Categorization in Motion: Duwamish Identity, 1792-1934 by Corey Susan O’Malley Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology University of California, Los Angeles, 2017 Professor Rebecca J. Emigh, Chair This study uses narrative analysis to examine how racial, ethnic, and national schemas were mobilized by social actors to categorize Duwamish identity from the eighteenth century to the early twentieth century. In so doing, it evaluates how the classificatory schemas of non- indigenous actors, particularly the state, resembled or diverged from Duwamish self- understandings and the relationship between these classificatory schemes and the configuration of political power in the Puget Sound region of Washington state. The earliest classificatory schema applied to the Duwamish consisted of a racial category “Indian” attached to an ethno- national category of “tribe,” which was honed during the treaty period. After the “Indian wars” of 1855-56, this ethno-national orientation was supplanted by a highly racialized schema aimed at the political exclusion of “Indians”. By the twentieth century, however, formalized racialized exclusion was replaced by a racialized ethno-national schema by which tribal membership was defined using a racial logic of blood purity.