Stutesman, John H.Toc.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download This List As PDF Here

QuadraphonicQuad Multichannel Engineers of 5.1 SACD, DVD-Audio and Blu-Ray Surround Discs JULY 2021 UPDATED 2021-7-16 Engineer Year Artist Title Format Notes 5.1 Production Live… Greetins From The Flow Dishwalla Services, State Abraham, Josh 2003 Staind 14 Shades of Grey DVD-A with Ryan Williams Acquah, Ebby Depeche Mode 101 Live SACD Ahern, Brian 2003 Emmylou Harris Producer’s Cut DVD-A Ainlay, Chuck David Alan David Alan DVD-A Ainlay, Chuck 2005 Dire Straits Brothers In Arms DVD-A DualDisc/SACD Ainlay, Chuck Dire Straits Alchemy Live DVD/BD-V Ainlay, Chuck Everclear So Much for the Afterglow DVD-A Ainlay, Chuck George Strait One Step at a Time DTS CD Ainlay, Chuck George Strait Honkytonkville DVD-A/SACD Ainlay, Chuck 2005 Mark Knopfler Sailing To Philadelphia DVD-A DualDisc Ainlay, Chuck 2005 Mark Knopfler Shangri La DVD-A DualDisc/SACD Ainlay, Chuck Mavericks, The Trampoline DTS CD Ainlay, Chuck Olivia Newton John Back With a Heart DTS CD Ainlay, Chuck Pacific Coast Highway Pacific Coast Highway DTS CD Ainlay, Chuck Peter Frampton Frampton Comes Alive! DVD-A/SACD Ainlay, Chuck Trisha Yearwood Where Your Road Leads DTS CD Ainlay, Chuck Vince Gill High Lonesome Sound DTS CD/DVD-A/SACD Anderson, Jim Donna Byrne Licensed to Thrill SACD Anderson, Jim Jane Ira Bloom Sixteen Sunsets BD-A 2018 Grammy Winner: Anderson, Jim 2018 Jane Ira Bloom Early Americans BD-A Best Surround Album Wild Lines: Improvising on Emily Anderson, Jim 2020 Jane Ira Bloom DSD/DXD Download Dickinson Jazz Ambassadors/Sammy Anderson, Jim The Sammy Sessions BD-A Nestico Masur/Stavanger Symphony Anderson, Jim Kverndokk: Symphonic Dances BD-A Orchestra Anderson, Jim Patricia Barber Modern Cool BD-A SACD/DSD & DXD Anderson, Jim 2020 Patricia Barber Higher with Ulrike Schwarz Download SACD/DSD & DXD Anderson, Jim 2021 Patricia Barber Clique Download Svilvay/Stavanger Symphony Anderson, Jim Mortensen: Symphony Op. -

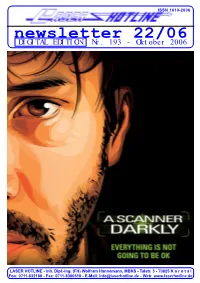

Newsletter 22/06 DIGITAL EDITION Nr

ISSN 1610-2606 ISSN 1610-2606 newsletter 22/06 DIGITAL EDITION Nr. 193 - Oktober 2006 Michael J. Fox Christopher Lloyd LASER HOTLINE - Inh. Dipl.-Ing. (FH) Wolfram Hannemann, MBKS - Talstr. 3 - 70825 K o r n t a l Fon: 0711-832188 - Fax: 0711-8380518 - E-Mail: [email protected] - Web: www.laserhotline.de Newsletter 22/06 (Nr. 193) Oktober 2006 editorial Hallo Laserdisc- und DVD-Fans, diesem Sinne sind wir guten Mutes, unse- liebe Filmfreunde! ren Festivalbericht in einem der kommen- Kennen Sie das auch? Da macht man be- den Newsletter nachzureichen. reits während der Fertigstellung des einen Newsletters große Pläne für den darauf Aber jetzt zu einem viel wichtigeren The- folgenden nächsten Newsletter und prompt ma. Denn wer von uns in den vergangenen wird einem ein Strich durch die Rechnung Wochen bereits die limitierte Steelbook- gemacht. So in unserem Fall. Der für die Edition der SCANNERS-Trilogie erwor- jetzt vorliegende Ausgabe 193 vorgesehene ben hat, der darf seinen ursprünglichen Bericht über das Karlsruher Todd-AO- Ärger über Teil 2 der Trilogie rasch ver- Festival musste kurzerhand wieder auf Eis gessen. Hersteller Black Hill ließ Folgen- gelegt werden. Und dafür gibt es viele gute des verlautbaren: Gründe. Da ist zunächst das Platzproblem. Im wahrsten Sinne des Wortes ”platzt” der ”Käufer der Verleih-Fassung der Scanners neue Newsletter wieder aus allen Nähten. Box haben sicherlich bemerkt, dass der Wenn Sie also bislang zu jenen Unglückli- 59 prall gefüllte Seiten - und das nur mit zweite Teil um circa 100 Sekunden gekürzt chen gehören, die SCANNERS 2 nur in anstehenden amerikanischen Releases! Des ist. -

FOR SALE ‐ GENESIS BOX SETS These Are All the Rhino Sets Distributed to the USA Through Amazon

FOR SALE ‐ GENESIS BOX SETS These are all the Rhino sets distributed to the USA through Amazon. All are in excellent condition. Each individual album includes the CD(s) and a DVD with the 5.1 files in NTSC/DVD‐Audio/DTS/Dolby Digital (except The Movie Box). DVDs also include some video extras. Artist Title Notes Price Genesis Green Box, 1970‐1975 Trespass; Nursery Cryme; Foxtrot; Selling $ 300.00 England By The Pound; The Lamb Lies Down On Broadway; Genesis 1970‐1975 Extras Genesis Blue Box, 1976‐1982 A Trick of the Tail; Wind & Wuthering; …and $ 300.00 then there were three; Duke; ababab; Genesis 1976‐1982 Extras Genesis Red Box, 1983‐1998 Genesis; Invisible Touch; We Can’t Dance; $ 200.00 …Calling All Stations; Genesis 1983‐1998 Extras Genesis Black Box, 1973‐2007 LIVE Live; Seconds Out; Three Sides Live; The Way $ 225.00 We Walk; Live Over Europe (2 CDs only, slot provided for this album which was not included as part of this set); Genesis Live 1973‐2007 Extras Genesis White Box, 1981‐2007 The Movie Box Three Sides Live (1 DVD); The Mama Tour (1 $ 80.00 DVD); Live at Wembley Stadium (1 DVD); The Way We Walk Live in Concert (1 DVD); The Movie Box 1981‐2007 Extras FOR SALE ‐ SACD STEREO Artist Title Notes Price PENDING SALE ‐ Boston Boston $ 12.00 Chicago Symphony/Dvorak New World Symphony $ 7.00 Dylan, Bob The Free Wheelin' Bob Dylan $ 12.00 Dylan, Bob Highway 61 revisited $ 10.00 Guaraldi Trio, Vince A Charlie Brown Christmas SACD Only $ 12.00 PENDING SALE ‐ Journey Escape SACD Only $ 12.00 The Police Synchronicity SACD Only $ 15.00 -

Personality and Dvds

personality FOLIOS and DVDs 6 PERSONALITY FOLIOS & DVDS Alfred’s Classic Album Editions Songbooks of the legendary recordings that defined and shaped rock and roll! Alfred’s Classic Album Editions Alfred’s Eagles Desperado Led Zeppelin I Titles: Bitter Creek • Certain Kind of Fool • Chug All Night • Desperado • Desperado Part II Titles: Good Times Bad Times • Babe I’m Gonna Leave You • You Shook Me • Dazed and • Doolin-Dalton • Doolin-Dalton Part II • Earlybird • Most of Us Are Sad • Nightingale • Out of Confused • Your Time Is Gonna Come • Black Mountain Side • Communication Breakdown Control • Outlaw Man • Peaceful Easy Feeling • Saturday Night • Take It Easy • Take the Devil • I Can’t Quit You Baby • How Many More Times. • Tequila Sunrise • Train Leaves Here This Mornin’ • Tryin’ Twenty One • Witchy Woman. Authentic Guitar TAB..............$22.95 00-GF0417A____ Piano/Vocal/Chords ...............$16.95 00-25945____ UPC: 038081305882 ISBN-13: 978-0-7390-4697-5 UPC: 038081281810 ISBN-13: 978-0-7390-4258-8 Authentic Bass TAB.................$16.95 00-28266____ UPC: 038081308333 ISBN-13: 978-0-7390-4818-4 Hotel California Titles: Hotel California • New Kid in Town • Life in the Fast Lane • Wasted Time • Wasted Time Led Zeppelin II (Reprise) • Victim of Love • Pretty Maids All in a Row • Try and Love Again • Last Resort. Titles: Whole Lotta Love • What Is and What Should Never Be • The Lemon Song • Thank Authentic Guitar TAB..............$19.95 00-24550____ You • Heartbreaker • Living Loving Maid (She’s Just a Woman) • Ramble On • Moby Dick UPC: 038081270067 ISBN-13: 978-0-7390-3919-9 • Bring It on Home. -

Jazz in the Pacific Northwest Lynn Darroch

Advance Praise “Lynn Darroch has put together a great resource for musicians, listeners, and history buffs, compiling what seems to be the most comprehensive resource about the history of jazz in the Northwest. This book will do the important job of keeping the memories and stories alive of musicians and venues that, while they may be immortalized through recordings, have important history that may otherwise be lost to the murkiness of time. Darroch has done the community and the music a great service by dedicating himself to telling these stories.” —John Nastos “Lynn Darroch illuminates the rich history of jazz in the Pacific Northwest from the early twentieth century to the present. Interweaving factors of culture, economics, politics, landscape, and weather, he helps us to understand how the Northwest grew so many fine jazz artists and why the region continues to attract musicians from New Orleans, New York, California, Europe, and South America. He concentrates on the traditions of the big port cities, Seattle and Portland, and underlines the importance of musicians from places like Wenatchee, Spokane, Eugene, and Bend. Darroch has the curiosity of a journalist, the investigative skills of a historian and the language of a poet. His writing about music makes you want to hear it.” —Doug Ramsey “With the skills of a curator, Lynn Darroch brings us the inspiring history and personal stories of Northwest jazz musicians whose need for home, love of landscape, and desire to express, all culminate into the unique makeup of jazz in Portland and Seattle. Thank you Lynn for a great read and its contribution to jazz. -

March 2021 BLUESLETTER Washington Blues Society in This Issue

LETTER FROM THE PRESIDENT WASHINGTON BLUES SOCIETY Hi Blues Fans! Proud Recipient of a 2009 I just finished watching our Keeping the Blues Alive Award 2021 Musicians Relief Fund/ HART Fundraiser and I must 2021 OFFICERS say I thought it was great. I am President, Tony Frederickson [email protected]@wablues.org so grateful for the generous Vice President, Rick Bowen [email protected]@wablues.org donation of the musical talents Secretary, Marisue Thomas [email protected]@wablues.org of John Nemeth & the Blues Treasurer, Ray Kurth [email protected]@wablues.org Dreamers, Theresa James, Terry Editor, Eric Steiner [email protected]@wablues.org Wilson & the Rhythm Tramps and Too Slim & the Taildraggers! 2021 DIRECTORS It was a good show and well worth reviewing again and again if Music Director, Open [email protected]@wablues.org you missed it! Also, a big shout out to Rick Bowen and Jeff Menteer Membership, Chad Creamer [email protected]@wablues.org for their talents for the production of this event. I also want to say Education, Open [email protected]@wablues.org “Thank You” to all of you who made donations! If you are looking Volunteers, Rhea Rolfe [email protected]@wablues.org for a little music to fill some time this would be a great three-hour Merchandise, Tony Frederickson [email protected]@wablues.org window and any donations you might be able to make would be very Advertising, Open [email protected]@wablues.org much appreciated. If you are interested go to our new YouTube page (Washington Blues Society) and check it out. -

Heart Alive in Seattle Mp3, Flac, Wma

Heart Alive In Seattle mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Alive In Seattle Country: Europe Released: 2003 Style: Classic Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1417 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1360 mb WMA version RAR size: 1795 mb Rating: 4.6 Votes: 518 Other Formats: APE MP4 MPC ADX XM AIFF MIDI Tracklist 1 Crazy On You 2 Sister Wild Rose 3 The Witch 4 Straight On 5 These Dreams 6 Mistral Wind 7 Alone 8 Dog And Butterfly 9 Mona Lisa And Mad Hatters 10 Battle Of Evermore 11 Heaven 12 Magic Man 13 Two Faces Of Eve 14 Love Alive 15 Break The Rock 16 Barracuda 17 Wild Child 18 Black Dog 19 Dreamboat Annie Companies, etc. Copyright (c) – Heart Amalgamated Copyright (c) – Image Entertainment Credits Bass Guitar – Mike Inez Drums, Percussion – Ben Smith Guitar, Acoustic Guitar, Lap Steel Guitar, Backing Vocals – Scott Olson Guitar, Acoustic Guitar, Vocals, Mandolin, Ukulele – Nancy Wilson Keyboards – Tom Kellock Vocals, Acoustic Guitar, Autoharp, Flute, Ukulele – Ann Wilson Notes Program Content and Artwork: (C) 2002 Heart Amalgamated. DVD Package Design: (c) MMIII Image Entertainment, Inc. Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 8 28765 10749 5 Label Code: LC00116 Rights Society: BIEM/GEMA Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year EPC 517327 2, Alive In Seattle EPC 517327 2, Heart Epic, Legacy Europe 2003 5173272000 (2xCD, Album) 5173272000 Alive In Seattle (2xSACD, Hybrid, E2H90287 Heart Epic, Legacy E2H90287 US 2003 Multichannel, Album) Universal Music Alive In Seattle DVD Video, 060252710057-9 Heart -

DVD Laser Disc Newsletter DVD Reviews Complete Index June 2008

DVD Laser Disc Newsletter DVD Reviews Complete Index June 2008 Title Issue Page *batteries not included May 99 12 "10" Jun 97 5 "Weird Al" Yankovic: The Videos Feb 98 15 'Burbs Jun 99 14 1 Giant Leap Nov 02 14 10 Things I Hate about You Apr 00 10 100 Girls by Bunny Yaeger Feb 99 18 100 Rifles Jul 07 8 100 Years of Horror May 98 20 1000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse Sep 00 2 101 Dalmatians Jan 00 14 101 Dalmatians Apr 08 11 101 Dalmatians (remake) Jun 98 10 101 Dalmatians II Patch's London Adventure May 03 15 10:30 P.M. Summer Sep 07 6 10th Kingdom Jul 00 15 11th Hour May 08 10 11th of September Moyers in Conversation Jun 02 11 12 Monkeys May 98 14 12 Monkeys (DTS) May 99 8 123 Count with Me Jan 00 15 13 Ghosts Oct 01 4 13 Going on 30 Aug 04 4 13th Warrior Mar 00 5 15 Minutes Sep 01 9 16 Blocks Jul 07 3 1776 Sep 02 3 187 May 00 12 1900 Feb 07 1 1941 May 99 2 1942 A Love Story Oct 02 5 1962 Newport Jazz Festival Feb 04 13 1979 Cotton Bowl Notre Dame vs. Houston Jan 05 18 1984 Jun 03 7 1998 Olympic Winter Games Figure Skating Competit May 99 7 1998 Olympic Winter Games Figure Skating Exhib. Sep 98 13 1998 Olympic Winter Games Hockey Highlights May 99 7 1998 Olympic Winter Games Overall Highlights May 99 7 2 Fast 2 Furious Jan 04 2 2 Movies China 9 Liberty 287/Gone with the West Jul 07 4 Page 1 All back issues are available at $5 each or 12 issues for $47.50. -

(September 2006)!

September 2006 • Volume 1, Issue 4 • The Official FREE Newsletter Of Widescreen Review Magazine Click here or sign up to receive this newsletter for FREE at WidescreenReview.com WELCOME! Welcome back to the fourth edition of the Widescreen Review Newsletter. Last month's featured interview with Joe Kane raised so much interest that the folks at Blu-ray were given the opportunity to strike back. In the upcoming print issue, October 2006, please make sure to read "Clearing The Air With The Blu-Ray Disc Association," featuring Don Eklund of Sony Pictures Home Entertainment and Chris Walker of Pioneer Electronics USA, Inc. This interview will also be available for all subscribers on WSR's Web site on September 15th. In addition to all the new format buzz, we bring you other cool interviews and Studio Scoop. We'd like to thank you all for your support and encourage you to pass this FREE newsletter along to your friends. Lastly, our sister publication, Ultimate Home Design, has launched their first newsletter, and it is available for anyone to download at www.ultimatehomedesign.com. This is an excellent way to expand your knowledge of the latest in green and sustainable building design and construction. As always, please feel free to submit your comments and suggestions, and enjoy this month’s edition. Congratulations to Barry Wilkinson, the winner of last month's Reader’s Poll. Gary Reber Editor-In-Chief, Widescreen Review COMING SOON TO NEWSSTANDS Here’s a sneak peek into what’s coming in Issue 113, October 2006 of Widescreen Review: • Danny Richelieu’ review of the ADA Cinema Rhapsody Mach III Home Theatre Controller • A review of Phase Technology dARTS System by John Kotches • Interview With Don Eklund & Chris Walker From Blu-ray Disc Association • Interview With Nordost’s Joe Reynolds • John Bishop talks about Scope Format Cinema For The Home • Assured Success In The Format War • Component Video In HD Versus SD By Joe Kane • Over 40 Blu-ray Disc, HD DVD, and DVD picture and sound quality reviews • And more.. -

Catalogo ENGLISH

catalogo ENGLISH - ITALIANO OVER 12000 DVD TITLES OF ROCK MUSIC - WE ARE THE BIGGEST ROCK VIDEO STORE ON INTERNET ALL OUR TITLES ON DVD ARE ORIGINALS - ARE NOT DVD-R BURNED COPIES!! HOW TO READ OUR DVD CATALOG 2012 1. NAME OF THE ARTIST/BAND - 2. TITLE OF VIDEO - 3. TIME IN MINUTES - 4. MEDIUM - 5. VIDEO/AUDIO QUALITY example: 1. AC/DC 2. LIVE AT SAINT LOUIS ARENA, DETROIT 1983 3. 55 4. DVD 5. ProShot ofic = Oficial Video; boot = Bootleg = image/audio quality is not alwais good but the historical value is high Proshot = is not a oficial video but the image/audio quality is HIGH! All DVD are delivered betwen 24/48 hours; COSTS Each title can include 1-2-3 DVD - The cost is for disk not for title. 1(one) DVD costs 9,99 €(euro) MINIMUN ORDER: 5 TITLES (OR 5 DVD) = 50 €(euro) FOR ORDERS GREATER THAN 20 TITLES THE COST OF 1 DVD IS 8,99 €(euro) FOR ORDERS GREATER THAN 50 TITLES THE COST OF 1 DVD IS 7,99 €(euro) more SHIPPING EXPENSES : from 9 euro to 15 ( weight and country) FOR FURTHER INFORMATIONS VISIT WWW.rockdvd.wordpress.com or WRITE US AT: [email protected] 1agina p catalogo ----------------------------------------------------------------------------- ITALIANO TUTTI I NOSTRI DVD SONO ORIGINALI E NON SONO COPIE SU DVD-R COME LEGGERE I TITOLI DEL CATALOGO 2012 1. NOME DEL ARTISTA - 2. TITOLO DEL VIDEO - 3. TEMPO IN MINUTI - 4. TIPO DI SUPPORTO - 5. QUALITA' AUDIO/VIDEO Esempio: 1. AC/DC 2. LIVE AT SAINT LOUIS ARENA, DETROIT 1983 3. -

Quadraphonicquad Multichannel Engineers of All Surround Releases

QuadraphonicQuad Multichannel Engineers of all surround releases JULY 2021 UPDATED 2021-7-16 Type Engineer Year Artist Title Format Notes 5.1 Production Live… Greetins From The Flow MCH Dishwalla Services, State MCH Abraham, Josh 2003 Staind 14 Shades of Grey DVD-A with Ryan Williams Quad Abramson, Mark 1973 Judy Collins Colors of the Day - The Best Of CD-4/Q8/QR/SACD MCH Acquah, Ebby Depeche Mode 101 Live SACD The Outrageous Dr. Stolen Goods: Gems Lifted from P: Alan Blaikley, Ken Quad Adelman, Jack 1972 Teleny's Incredible CD-4/Q8/QR/SACD the Masters Howard Plugged-In Orchestra MCH Ahern, Brian 2003 Emmylou Harris Producer’s Cut DVD-A MCH Ainlay, Chuck David Alan David Alan DVD-A MCH Ainlay, Chuck 2005 Dire Straits Brothers In Arms DVD-A DualDisc/SACD MCH Ainlay, Chuck Dire Straits Alchemy Live DVD/BD-V MCH Ainlay, Chuck Everclear So Much for the Afterglow DVD-A MCH Ainlay, Chuck George Strait One Step at a Time DTS CD MCH Ainlay, Chuck George Strait Honkytonkville DVD-A/SACD MCH Ainlay, Chuck 2005 Mark Knopfler Sailing To Philadelphia DVD-A DualDisc MCH Ainlay, Chuck 2005 Mark Knopfler Shangri La DVD-A DualDisc/SACD MCH Ainlay, Chuck Mavericks, The Trampoline DTS CD MCH Ainlay, Chuck Olivia Newton John Back With a Heart DTS CD MCH Ainlay, Chuck Pacific Coast Highway Pacific Coast Highway DTS CD MCH Ainlay, Chuck Peter Frampton Frampton Comes Alive! DVD-A/SACD MCH Ainlay, Chuck Trisha Yearwood Where Your Road Leads DTS CD MCH Ainlay, Chuck Vince Gill High Lonesome Sound DTS CD/DVD-A/SACD QSS: Ron & Howard Quad Albert, Ron & Howard 1975 -

Brand New Cd & Dvd Releases 2004 5,000+ Top Sellers

BRAND NEW CD & DVD RELEASES 2004 5,000+ TOP SELLERS COB RECORDS, PORTHMADOG, GWYNEDD,WALES, U.K. LL49 9NA Tel. 01766 512170: Fax. 01766 513185: www. cobrecords.com // e-mail [email protected] CDs, Videos, DVDs Supplied World-Wide At Discount Prices – Exports Tax Free SYMBOLS USED - IMP = Imports. r/m = remastered. + = extra tracks. D/Dble = Double CD. *** = previously listed at a higher price, now reduced Please read this listing in conjunction with our “ CDs AT SPECIAL PRICES” feature as some of the more mainstream titles may be available at cheaper prices in that listing. Please note that all items listed on this 2004 5,000+ titles listing are all of U.K. manufactured (apart from Imports which are denoted IM or IMP). Titles listed on our list of SPECIALS are a mix of U.K. and E.C. manufactured product. We will supply you with whichever item for the price/country of manufacture you choose to order. 695 10,000 MANIACS campfire songs Double B9 14.00 713 ALARM in the poppy fields X4 12.00 793 ASHER D. street sibling X2 12.80 866 10,000 MANIACS time capsule DVD X1 13.70 859 ALARM live in the poppy fields CD/DVD X1 13.70 803 ASIA aqua *** A5 7.50 874 12 STONES potters field B2 10.50 707 ALARM raw E8 7.50 776 ASIA arena *** A5 7.50 891 13 SENSES the invitation B2 10.50 706 ALARM standards E8 7.50 819 ASIA aria A5 7.50 795 13 th FLOOR ELEVATORS bull of the woods A5 7.50 731 ALARM, THE eye of the hurricane *** E8 7.50 809 ASIA silent nation R4 13.40 932 13 TH FLOOR ELEVATORS going up-very best of A5 7.50 750 ALARM, THE in the poppyfields X3