Table of Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Theosophist

THE THEOSOPHIST VOL. 135 NO. 7 APRIL 2014 CONTENTS On the Watch-Tower 3 M. P. Singhal The many lives of Siddhartha 7 Mary Anderson The Voice of the Silence — II 13 Clara Codd Charles Webster Leadbeater and Adyar Day 18 Sunita Maithreya Regenerating Wisdom 21 Krishnaphani Spiritual Ascent of Man in Secret Doctrine 28 M. A. Raveendran The Urgency for a New Mind 32 Ricardo Lindemann International Directory 38 Editor: Mr M. P. Singhal NOTE: Articles for publication in The Theosophist should be sent to the Editorial Office. Cover: Common Hoope, Adyar —A. Chandrasekaran Official organ of the President, founded by H. P. Blavatsky, 1879. The Theosophical Society is responsible only for official notices appearing in this magazine. 1 THE THEOSOPHICAL SOCIETY Founded 17 November 1875 President: Vice-President: Mr M. P. Singhal Secretary: Dr Chittaranjan Satapathy Treasurer: Mr T. S. Jambunathan Headquarters: ADYAR, CHENNAI (MADRAS) 600 020, INDIA Secretary: [email protected] Treasury: [email protected] Adyar Library and Research Centre: [email protected] Theosophical Publishing House: [email protected] & [email protected] Fax: (+91-44) 2490-1399 Editorial Office: [email protected] Website: http://www.ts-adyar.org The Theosophical Society is composed of students, belonging to any religion in the world or to none, who are united by their approval of the Society’s Objects, by their wish to remove religious antagonisms and to draw together men of goodwill, whatsoever their religious opinions, and by their desire to study religious truths and to share the results of their studies with others. Their bond of union is not the profession of a common belief, but a common search and aspiration for Truth. -

Sacred Places

SACRED PLACES HOW TO PERCEIVE, PRESERVE AND CO-CREATE THEM WITH KURT LELAND 2 JUNE 2019 ORGANISED BY THEOSOPHICAL SOCIETY IN THE NETHERLANDS INTERNATIONAL THEOSOPHICAL CENTRE Place: BESANT HALL MEENTWEG 9, 1411 GR NAARDEN SACRED PLACES Sacred Places The program Time Table: 2 June 2019 Many of us have experienced the Theosophical teachings on subtle 10.00 Arrival and coffee calming, peaceful, uplifting charac- planes and beings provide a useful 10.30 Opening and lecture: Perceiving and Preserving Sacred Places ter of sacred places, perhaps in a template for understanding the 12.00 Lunch break. Bring your own sandwiches! church, a favourite place in nature, powers latent in sacred places and 13.00 Lecture: Devas (Angels) and the Co-Creation of Sacred Space or an ancient site of pilgrimage and how to attune ourselves to them. Join 14.30 Angels of the Four Corners: A Practice worship. These are places where Theosophical clairvoyant Kurt Leland 16:00 Developing Unity Consciousness: A Meditation it seems that our inner and outer in an experiential investigation of our 16.30 Closing worlds, the soul and body, come relationship to sacred places and their together and we feel restored and power to heal and make us whole. whole. In this daylong workshop, we will explore the outer characteristics More programs on powers The International Theo- of sacred places, such as the many latent in humankind sophical Centre forms they take, as well as their This day is the kick-off of a range of The ITC aims to be an active and inner characteristics, the energies programs organized on this subject inspiring spiritual centre, contri- and beings that sustain them. -

'Theosophy and Occultism As Taught by Madame Blavatsky 'Theosophy Annie Besan.T, D.Litt., P.'F.S

'Theosophy and Occultism As Taught by Madame Blavatsky 'Theosophy Annie Besan.t, D.Litt., P.'f.S. Questions and An~wers Rt. Rev. C.W. Leadbeater A Vision of the Future George S. Arundale, M.A., D.Litt. 'The Occult .Cife Capt. Leo L. Partlow july, 1932 'Theosophy Occultism r,~,,...-9<:"N,,...-9=,~,,~,,~,,~,~ ~ Our Policy ~ W orld Theosophy is an unsectarian publica- - l tion dedicated to the art of livingt to world ~ ' ~ Brotherhoodt and to the dissemination of truth. f - Theosophy means Divine Wisdom. - j Contributions will be considered on the sub- ~ S' jects of Theosophyt philosophyt religiont educa- z i tiont sciencet psychologyt artt healtht citizen- ! ~ shipt social servicet and all other branches of ~ S' humanitarian endeavor. z '~~ . Contributors are earnestly requested to re- ~i: member that harmony t understandingt and eo- = operation are vital essentials of practical brother- ,_~ hoodt .and are impeded by coritroversial opinions i_~ S' of a criticalt personal nature. z 2 .The . pages of this magazine are open to all - i_· phases , of thought provided they are in conso- ~ S' nance with the ideals of Theosophy. But the ~ \.! z: Editor is not responsible for any declarations of I. ~ opinions expressed by contributors. · ~ S' uThe inquirg of trutht which is the lorJe-mak- , l ing or wooing of it; the knowledge of truth, the ä ts preference of it; and the belief of truth, the enjoy- ~ S' ing of it, is the sovereigp good of human nature.,, , {,. ' ' j ~"'''~.j..~11~.j._~ll~.j._~ll~.j._~ll~.j._~ll~.j..~ll~J.~1~:ffl World 'Theosoph.Y A Journal Devoted to the Art of Living Marie R. -

The Theosophical Seal by Arthur M. Coon the Theosophical Seal a Study for the Student and Non-Student

The Theosophical Seal by Arthur M. Coon The Theosophical Seal A Study for the Student and Non-Student by Arthur M. Coon This book is dedicated to all searchers for wisdom Published in the 1800's Page 1 The Theosophical Seal by Arthur M. Coon INTRODUCTION PREFACE BOOK -1- A DIVINE LANGUAGE ALPHA AND OMEGA UNITY BECOMES DUALITY THREE: THE SACRED NUMBER THE SQUARE AND THE NUMBER FOUR THE CROSS BOOK 2-THE TAU THE PHILOSOPHIC CROSS THE MYSTIC CROSS VICTORY THE PATH BOOK -3- THE SWASTIKA ANTIQUITY THE WHIRLING CROSS CREATIVE FIRE BOOK -4- THE SERPENT MYTH AND SACRED SCRIPTURE SYMBOL OF EVIL SATAN, LUCIFER AND THE DEVIL SYMBOL OF THE DIVINE HEALER SYMBOL OF WISDOM THE SERPENT SWALLOWING ITS TAIL BOOK 5 - THE INTERLACED TRIANGLES THE PATTERN THE NUMBER THREE THE MYSTERY OF THE TRIANGLE THE HINDU TRIMURTI Page 2 The Theosophical Seal by Arthur M. Coon THE THREEFOLD UNIVERSE THE HOLY TRINITY THE WORK OF THE TRINITY THE DIVINE IMAGE " AS ABOVE, SO BELOW " KING SOLOMON'S SEAL SIXES AND SEVENS BOOK 6 - THE SACRED WORD THE SACRED WORD ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Page 3 The Theosophical Seal by Arthur M. Coon INTRODUCTION I am happy to introduce this present volume, the contents of which originally appeared as a series of articles in The American Theosophist magazine. Mr. Arthur Coon's careful analysis of the Theosophical Seal is highly recommend to the many readers who will find here a rich store of information concerning the meaning of the various components of the seal Symbology is one of the ancient keys unlocking the mysteries of man and Nature. -

Be Ye Perfect

BE YE PERFECT by Geoffrey Hodson CONTENTS Preface Part I FROM THE UNREAL TO THE REAL Chapter 1- The Babe Chapter 2- From Birth to Ten Years Old Chapter 3- The Principles of Education Chapter 4- From Ten to Twenty Years Chapter 5- From Twenty to Forty Years Chapter 6- From Forty to Eighty Years Part II THE THREE PATHS Chapter 7- The Way of Will Chapter 8- The Way of Knowledge Chapter 9- The Way of Love PREFACE THIS book is the second of the series containing the teachings received from the angel who inspired the volume entitled The Brotherhood of Angels and of Men. Though some may dismiss these present teachings as being entirely impracticable, I nevertheless offer them for consideration because I believe that they contain much that is of value and significance at the present time, when the changing race-consciousness is finding old methods of education inadequate, and new ones are everywhere sought. The errors and deficiencies of the book are due to my lack of competence to receive the angel's teaching in all its clarity and beauty; my hope is that gleams of the light of his wisdom may find their way through the darkness of my limitations and may serve to illumine the minds that are open to receive them; and particularly those responsible for the upbringing of the children of the new age. Only broad outlines are sketched in this volume, offered now at the dawn of a new day in the evolution of race-consciousness; more detailed teaching may be expected as the sun climbs towards his zenith, for then human and angel consciousness will be united to form one splendid channel for the power, the wisdom, and the knowledge of That which is their common source. -

The Inner Side of Church Worship by Father Geoffrey Hodson

The Inner Side Of Church Worship by Father Geoffrey Hodson FOREWORD by Archbishop Frank W. Pigott CATHOLIC Christians claim that the Church, with its threefold ministry tracing spiritual descent by the laying on of hands from the earliest Apostles of Our Lord, its seven sacraments or means of grace and its elaborate ceremonial, is a Divine Society; that is to say, it is a body corporate which is ensouled by the life of the Lord Himself; or, changing the metaphor without in any way changing the sense, it is an apparatus, a piece of intricate mechanism, by means of which grace or spiritual benediction is brought from on high and distributed far and wide on the Lord's people here in this world 'in the body pent '. It is a high claim to make and, indeed, an unique claim; there does not seem to be any other society or organization in the world which makes quite such a claim as that. Yet the Catholic Church makes that claim unflinchingly and has been making it for something like two thousand years. It is worth while examining the basis of such a claim. What are the grounds on which Catholic Christians for so long a time have dared to claim that their Church is a Divine Society, and still make the claim? Briefly they are three. First, there is tradition. Since the very beginning the belief that the Lord gives Himself to His people in His church by the operation of the Holy Spirit has been held by Catholic Christians and handed on from generation to generation. -

The Theosophist

THE THEOSOPHIST VOL. 134 NO. 4 JANUARY 2013 CONTENTS Presidential Address 3 Radha Burnier The Search for Truth 13 Bhupendra R. Vora The Evolution of the Universe 22 Annie Besant Life — a Movie, a School, a Pilgrimage 27 D. P. Sabnis Spirituality at the Workplace 29 F. M. Sahoo International Directory 38 Editor: Mrs Radha Burnier NOTE: Articles for publication in The Theosophist should be sent to the Editorial Office. Cover: Nandi Bull and Jackfruits at the Adyar Theatre — Prof. C. A. Shinde Official organ of the President, founded by H. P. Blavatsky, 1879. The Theosophical Society is responsible only for official notices appearing in this magazine. 1 THE THEOSOPHICAL SOCIETY Founded 17 November 1875 President: Mrs Radha Burnier Vice-President: Mr M. P. Singhal Secretary: Mrs Kusum Satapathy Treasurer: Mr T. S. Jambunathan Headquarters: ADYAR, CHENNAI (MADRAS) 600 020, INDIA Secretary: [email protected] Treasury: [email protected] Adyar Library and Research Centre: [email protected] Theosophical Publishing House: [email protected] & [email protected] Fax: (+91-44) 2490-1399 Editorial Office: [email protected] Website: http://www.ts-adyar.org The Theosophical Society is composed of students, belonging to any religion in the world or to none, who are united by their approval of the Society’s Objects, by their wish to remove religious antagonisms and to draw together men of goodwill, whatsoever their religious opinions, and by their desire to study religious truths and to share the results of their studies with others. Their bond of union is not the profession of a common belief, but a common search and aspiration for Truth. -

Theosophy and Krishnamurti: Harmonies and Tensions

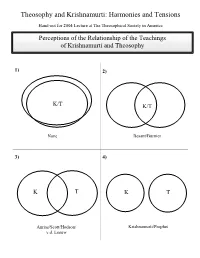

Theosophy and Krishnamurti: Harmonies and Tensions Hand-out for 2004 Lecture at The Theosophical Society in America Perceptions of the Relationship of the Teachings of Krishnamurti and Theosophy 1) 2) K/T K/T None Besant/Burnier 3) 4) K T K T Anrias/Scott/Hodson/ Krishnamurti/Prophet v.d. Leeuw Theosophical Perceptions of World Teacher Project Genuine Not Genuine Annie Besant K (1980s) Rom Landau Radha Burnier Ouspensky Jean Overton Fuller uccessful Aryel Sanat S C.W. Leadbeater Rudolf Steiner Geoffrey Hodson A. Smythe Scott/Anrias E.L. Gardner Alice Bailey K (1930’s) Failed Ballard/Prophet Comparison between Theosophy and Krishnamurti Category Theosophy Krishnamurti Motto "There is no religion higher "Truth is a pathless land" than truth" Aspects of truth "some portions … "truth has no aspects" proclaimed" Theoretical vs. personal "truth by direct experience" "… through observation" Comparison "Contrast alone …" " … is not understanding " Higher and lower selves 3-fold nature of Self "an idea, not a fact" Reincarnation Part of "pivotal doctrine" "immaterial" Spiritual path(s) Many or One "Truth is a pathless land" (Spiritual) Evolution "perpetual progress for each "Doesn’t exist" "Life can incarnating Ego" not have a plan" Ladders "No single rung of the ladder "the ladder of hierarchical … can be skipped" achievement, is utterly false" Masters "undeniable existence" "Your own projections" Mediators Send out periodically Exploiters Nationalism/Patriotism To be awakened Absurd and cruel Ceremonies "have their place … [and] use "illusions" -

The Miracle of Birth

THE MIRACLE OF BIRTH A Clairvoyant Study of Prenatal Life by GEOFFREY HODSON First Published 1929 TO MY GODCHILD HEATHER AND HER PARENTS WITHOUT WHOM THIS BOOK COULD NOT HAVE BEEN WRITTEN "Uplift the women of your race till all are seen as queens, and to such queens let every man be as a king, that each may honour each, seeing the other's royalty. Let every home, however small, become a court, every son a knight, every child a page. Let all treat all with chivalry, honouring in each their royal parentage, their kingly birth; for there is royal blood in every man; all are the children of the King." "The Brotherhood of Angels and of Men." INTRODUCTION At the time when the crying need for the reduction of maternal and infant mortality is at last receiving some attention the publication of this book is most opportune. Socrates taught that "the beginning is the most important part of any work, especially in dealing with anything young and tender". In our day Sir Frederick Truby King is pointing out that if racial health is to be improved the first eighteen months (nine pre-natal, nine post-natal) are the most important. More and more is it being realised that the foundations of physical, emotional and mental health are laid before birth, and this book throws an interesting light on the laying of these foundations. Studies such as these help towards the better understanding of the miracle of birth and so foster that respect for motherhood which is surely the mark of truly civilised communities. -

Thus Have I Heard by Geoffrey Hodson

THUS HAVE I HEARD By Geoffrey Hodson GODSPEED I AM happy to have the privilege, as on a former occasion, of bidding Godspeed to an offering from Geoffrey Hodson to the world. His life is dedicated to kindliness, to helpfulness, and he has the good fortune of being a link with non-human agencies animated like himself by a practical spirit of goodwill. Thus equipped, Geoffrey Hodson adds this further record of conclusions to which he has so far come regarding the Science of Growth, or the Science of Life-Growth and Life are one. I have read with interest and profit previous records, and I have read this one with no less satisfaction, for it discloses the important fact that the writer is tremendously sincere, that he is eager to help, and that he knows what he is writing about. It really does not matter what people say or write, it matters less whether or not we agree with them; but it matters very much that they should have a profound conviction that their utterances are vibrantly true. Readers of this book may not find everything in it congenial to their needs, other pathways may, appeal to them more; yet herein is depicted a well- trodden road which some know leads to the One Goal. It is profoundly interesting to study roads that others tread and to note the marks which distinguish them from one’s own road. One can tread one’s own road more effectively, more swiftly, for a knowledge of the roads of others, for in essence all roads are one. -

Rays & Human Unfoldment

TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction . 2 Ray 6 .................................. 43 Ray 1 .................................. 7 Ray 7 .................................. 50 Ray 2 .................................. 18 The Rays & Human Unfoldment . 56 Ray 3 .................................. 25 The Rays of Greater Wholes . 59 Ray 4 .................................. 31 Miscellanea ............................. 63 Ray 5 .................................. 37 Outgoing 6th Ray—Incoming 7th Ray . 64 COMPILER’S NOTE Throughout the writings of Alice Bailey is scattered a specifically to the effect on our civilization of the wealth of information about the Seven Rays. The purpose outgoing 6th Ray and the incoming 7th Ray. of this compilation is to gather into a single volume that In the sections on each individual Ray, I was faced with portion of the material which pertains directly to humanity the problem of how best to arrange the material, for several and human life, and which is therefore of immediate practi- quite different ways suggested themselves. After consider- cal value to those who study the Ageless Wisdom and seek able deliberation, I decided on an arrangement which be- to implement its methods in their lives. gins approximately with the most accessible material and The material is arranged in the following manner: ends with the least accessible. But in the final analysis the 1. General introductory information about the Rays, order is relatively unimportant, for the real value lies only definitions, their nature, function, value of studying in the overall impression created by the excerpts in their them, etc. totality. 2. A section on each Ray and its effect on the Soul; The individual passages themselves range from entire personality; and mental, emotional, and physical sections to only parts of sentences. -

Theosophical Society Collection.Doc

Special Collections and Archives: Theosophical Society Collection This collection was transferred to the University of Sheffield Library’s Special Collections department from the National Centre for English Cultural Tradition in 2007, and comprises around 500 books relating to the topic of Theosophy, a doctrine of religious philosophy and metaphysics which developed in the late 19th century. A. E., 1867-1935 Collected poems ; by A. E.. - London : Macmillan, 1920. [v2613994] THEOSOPHICAL SOCIETY COLLECTION 1 200351227 A. F. Leaves from a northern university ; by A. F.. - London : Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner, 1926. [M0012686SH] THEOSOPHICAL SOCIETY COLLECTION 2 200351228 Adams, W. Marsham The book of the master, or, The Egyptian doctrine of the light born of the virgin mother ; by W. Marsham Adams. - London : John Murray; New York : Putnam's, 1898. [M0012687SH] THEOSOPHICAL SOCIETY COLLECTION 3 200351229 Adams, W. R. C. Coode A primer of occult physics ; by W. R. C. Coode Adams. - London : Theosophical Publishing House, 1927. [M0012688SH] THEOSOPHICAL SOCIETY COLLECTION 4 200351230 Alcyone At the feet of the master ; by Alcyone (J. Krishnamurti). - English ed.. - London : Theosophical Publishing House, 1911. [M0012690SH] THEOSOPHICAL SOCIETY COLLECTION 5 200351231 Ames, Alice C. Meditations ; by Alice C. Ames. - London : Theosophical Publishing Society, 1908. [M0012782SH] THEOSOPHICAL SOCIETY COLLECTION 6 200351232 Ames, Alice C. Eternal consciousness, being Vol.II of "Meditations" ; by Alice C. Ames. - London : Theosophical Publishing