Out-Migration from Kampung Awah a Settlement Scheme in Jengka

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MSPO Public Summary Report Revision 1 (Feb 2020)

PF824 MSPO Public Summary Report Revision 1 (Feb 2020) MALAYSIAN SUSTAINABLE PALM OIL - ANNUAL SURVEILLANCE ASSESSMENT (ASA2) Public Summary Report Lembaga Minyak Sawit Malaysia Cawangan Temerloh Client company Address: Lembaga Minyak Sawit Malaysia Cawangan Temerloh Tingkat 2, Bangunan Tabung Haji 28000 Temerloh, Pahang, Malaysia Certification Unit: MPOB Sustainable Palm Oil Cluster (SPOC) Maran C2 Location of Certification Unit: Lembaga Minyak Sawit Malaysia Cawangan Temerloh Tingkat 2, Bangunan Tabung Haji 28000 Temerloh, Pahang, Malaysia Report prepared by: Hu Ning Shing (Lead Auditor) Report Number: 3091818 Assessment Conducted by: BSI Services Malaysia (DSM Accreditation Number: MSPO 09112018 CB 12) Suite 29.01 Level 29 The Gardens North Tower Mid Valley City Lingkaran Syed Putra 59200 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia Tel +60392129638 Fax +60392129639 www.bsigroup.com Page 1 of 79 PF824 MSPO Public Summary Report Revision 1 (Feb 2020) TABLE OF CONTENTS Page No Section 1: Executive Summary ........................................................................................ 3 1.1 Organizational Information and Contact Person ........................................................ 3 1.2 Certification Information ......................................................................................... 3 1.3 Location of Certification Unit ................................................................................... 3 1.4 Certified Area ....................................................................................................... -

Bil Bahagian / Negeri Nama Pegawai Jawatan / Gred

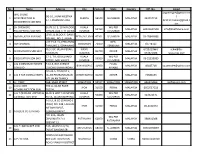

SENARAI PERLANTIKAN PEGAWAI PEMERIKSA ASET TUMBUHAN JAWATAN ALAMAT DAN NO. TEL BIL BAHAGIAN / NEGERI NAMA PEGAWAI ALAMAT EMAIL / GRED PEJABAT KETUA PEGAWAI PEMERIKSA ASET TUMBUHAN Jabatan Pertanian Bahagian Pengurusan Pegawai Tadbir Aras 11, Wisma Tani 1. Jabatan Pertanian Mohd Sazali bin Mohd Zin Diplomatik No. 30 Persiaran Perdana [email protected] M54 62624 Putrajaya No. Tel: 03-8870 3402 No. Fax: 03-8888 6242 BAHAGIAN PADI, TANAMAN INDUSTRI & FLORIKULTUR Jabatan Pertanian Bahagian Padi, Tanaman Industri Dan Florikultur Pegawai Pertanian 1. Bhg. PTIF, Putrajaya Zaifiwan bin Mat Zin Aras 12, No.30 Persiaran Perdana [email protected] G44 Presint 4, 62624 Putrajaya No. Tel: 03-8870 3294 No. Fax: 03-8888 9295 Jabatan Pertanian Bahagian Padi, Tanaman Industri Dan Florikultur Pegawai Pertanian 2. Bhg. PTIF, Putrajaya Hartini binti Yusuf Aras 12, No.30 Persiaran Perdana [email protected] G44 Presint 4, 62624 Putrajaya No. Tel: 03-8870 3278 No. Fax: 03-8888 9295 Jabatan Pertanian Bahagian Padi, Tanaman Industri Dan Florikultur Pegawai Pertanian 3. Bhg. PTIF, Putrajaya Siti Farah binti Halim Aras 12, No.30 Persiaran Perdana [email protected] G41 Presint 4, 62624 Putrajaya No. Tel: 03-8870 3296 No. Fax: 03-8888 9295 1 JAWATAN ALAMAT DAN NO. TEL BIL BAHAGIAN / NEGERI NAMA PEGAWAI ALAMAT EMAIL / GRED PEJABAT Jabatan Pertanian Bahagian Padi, Tanaman Industri Dan Florikultur Pegawai Pertanian 4. Bhg. PTIF, Putrajaya Nurwahidah binti Mohamad Aras 12, No.30 Persiaran Perdana [email protected] G41 Presint 4, 62624 Putrajaya No. Tel: 03-8870 3295 No. Fax: 03-8888 9295 Jabatan Pertanian Bahagian Padi, Tanaman Industri Dan Florikultur Pegawai Pertanian 5. -

Conglomerate from Setia Jasa Near Temerloh, Pahang, Peninsular Malaysia: Its Stratigraphic Position and Depositional Environment

Geological Society of Malaysia Annual Geological Conference 2001 June 2-3 2001, Pangkor island, Perak Darul Ridzuan, Malaysia Conglomerate from Setia Jasa near Temerloh, Pahang, Peninsular Malaysia: Its stratigraphic position and depositional environment MoHo SHAFEEA LEMAN1 AND MASATOSHI SoNE2·* 1Geology Programme, School of Environmental Science and Natural Resources, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, 43600 Bangi, Selangor, Malaysia 2lnstitute for Environment and Development (LESTARI), Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, 43600 Bangi, Selangor, Malaysia 'Present address: Asia Centre, University of New England, Armidale, NSW 2351, Australia Abstract: A thick sequence of conglomerate, tuffaceous sandstone and shale/mudstone largely exposed at the Setia Jasa area is described. The matrix-supported conglomerate of very well rounded clasts conformably overlies pebbly mudstone and shows a gradual change in matrix grain size from clay to sand. An Anisian (early Middle Triassic) age is indicated for a whole sequence by the presence of an ammonoid Paraceratites sp. found in a lower shale bed. Sedimentological features suggest that the conglomerate and underlying sandstone/shale sequences were possibly deposited in a relatively deep marine environment, and probably belong to the Semantan Formation. Abstrak: Satu jujukan tebal konglomerat, batu pasir bertuf dan syallbatu lumpur yang tersingkap di kawasan Setia Jasa diperihalkan di sini. Konglomerat sokongan matriks dengan klasta sangat bulat didapati menindih batu lumpur berpebel dan menunjukkan perubahan berterusan matriks dari saiz lumpur ke saiz pasir. Keseluruhan jujukan ditafsirkan berusia Anisian (Trias Tengah) berdasarkan kehadiran fosil amonoid Paraceratites sp. yang ditemui dalam syal di bawahnya. Bukti-bukti sedimentologi mencadangkan bahawa jujukan konglomerat dan jujukan batu pasir-syal di bawahnya mungkin diendapkan di sekitaran laut yang agak dalam dan mungkin merupakan sebahagian daripada Formasi Semantan. -

Syor-Syor Yang Dicadangkan Bagi Bahagian-Bahagian

SYOR-SYOR YANG DICADANGKAN BAGI BAHAGIAN-BAHAGIAN PILIHAN RAYA PERSEKUTUAN DAN NEGERI BAGI NEGERI PAHANG SEBAGAIMANA YANG TELAH DIKAJI SEMULA OLEH SURUHANJAYA PILIHAN RAYA DALAM TAHUN 2017 PROPOSED RECOMMENDATIONS FOR FEDERAL AND STATE CONSTITUENCIES FOR THE STATE OF PAHANG AS REVIEWED BY THE ELECTION COMMISSION IN 2017 PERLEMBAGAAN PERSEKUTUAN SEKSYEN 4(a) BAHAGIAN II JADUAL KETIGA BELAS SYOR-SYOR YANG DICADANGKAN BAGI BAHAGIAN-BAHAGIAN PILIHAN RAYA PERSEKUTUAN DAN NEGERI BAGI NEGERI PAHANG SEBAGAIMANA YANG TELAH DIKAJI SEMULA OLEH SURUHANJAYA PILIHAN RAYA DALAM TAHUN 2017 Suruhanjaya Pilihan Raya, mengikut kehendak Fasal (2) Perkara 113 Perlembagaan Persekutuan, telah mengkaji semula pembahagian Negeri Pahang kepada bahagian- bahagian pilihan raya Persekutuan dan bahagian-bahagian pilihan raya Negeri setelah siasatan tempatan kali pertama dijalankan mulai 14 November 2016 hingga 15 November 2016 di bawah seksyen 5, Bahagian II, Jadual Ketiga Belas, Perlembagaan Persekutuan. 2. Berikutan dengan kajian semula itu, Suruhanjaya Pilihan Raya telah memutuskan di bawah seksyen 7, Bahagian II, Jadual Ketiga Belas, Perlembagaan Persekutuan untuk menyemak semula syor-syor yang dicadangkan dan mengesyorkan dalam laporannya syor-syor yang berikut: (a) tiada perubahan bilangan bahagian-bahagian pilihan raya Persekutuan bagi Negeri Pahang; (b) tiada perubahan bilangan bahagian-bahagian pilihan raya Negeri bagi Negeri Pahang; (c) tiada pindaan atau perubahan nama kepada bahagian-bahagian pilihan raya Persekutuan dalam Negeri Pahang; dan (d) tiada pindaan atau perubahan nama kepada bahagian-bahagian pilihan raya Negeri dalam Negeri Pahang. 3. Jumlah bilangan pemilih seramai 740,023 orang dalam Daftar Pemilih semasa iaitu P.U. (B) 217/2016 yang telah diperakui oleh SPR dan diwartakan pada 13 Mei 2016 dan dibaca bersama P.U. -

Submarine Mass-Transport Deposits in the Semantan Formation (Middle-Upper Triassic), Central Peninsular Malaysia

Bulletin of the Geological Society of Malaysia 56 (2010) 15 – 26 Submarine mass-transport deposits in the Semantan Formation (Middle-Upper Triassic), central Peninsular Malaysia Mazlan Madon Petronas Research Sdn Bhd, Lot 3288-3289, Kawasan Institusi Bangi, 43000 Kajang, Malaysia Email address: [email protected] Abstract — Relatively fresh exposures of the Semantan Formation along the East-Coast Highway (Lebuhraya Pantai Timur – Fasa 1) between Karak and Kuantan, central Peninsular Malaysia, have given new insights into the sedimentary processes in the Triassic flysch basin that once separated west and east Malaya. An eastward change from distal to proximal facies between Karak and Maran indicates a west-facing, active continental shelf to slope sedimentation. Outcrops between Karak and Temerloh, east of the Late Triassic-Early Jurassic Bentong-Raub collisional suture, are generally characterized by “classical” flysch-like, thinly-bedded sandstone-mudstone facies. Further east of Temerloh towards Maran, and nearer to the paleo-shelf and slope, more sandy and thick-bedded turbidite facies occur. A proximal deep- marine facies association in the Semantan Formation is exposed at the Chenor Junction (Exit 821), kilometre 139 along the highway. South- and north-facing cuts on either sides of the highway reveal large gravity-slide blocks (megaclasts), slumps, debris flow deposits, and associated syn-sedimentary thrust faults and glide surfaces. These features are strongly indicative of large-scale submarine mass-transport processes on the palaeo-slope of the Triassic active margin. The Chenor mass-transport complex is made up of zones of incoherent slump deposits intercalated with well-bedded turbidite/debrite facies. In the lower part of the succession, there are megaclasts of sandstone-mudstone facies, measuring several metres in size, encased in a plastically deformed silty matrix. -

KKM HEADQUARTERS Division / Unit Activation Code PEJABAT Y.B. MENTERI 3101010001 PEJABAT Y.B

KKM HEADQUARTERS Division / Unit Activation Code PEJABAT Y.B. MENTERI 3101010001 PEJABAT Y.B. TIMBALAN MENTERI 3101010002 PEJABAT KETUA SETIAUSAHA 3101010003 PEJABAT TIMBALAN KETUA SETIAUSAHA (PENGURUSAN) 3101010004 PEJABAT TIMBALAN KETUA SETIAUSAHA (KEWANGAN) 3101010005 PEJABAT KETUA PENGARAH KESIHATAN 3101010006 PEJABAT TIMBALAN KETUA PENGARAH KESIHATAN (PERUBATAN) 3101010007 PEJABAT TIMBALAN KETUA PENGARAH KESIHATAN (KESIHATAN AWAM) 3101010008 PEJABAT TIMBALAN KETUA PENGARAH KESIHATAN (PENYELIDIKAN DAN SOKONGAN TEKNIKAL) 3101010009 PEJABAT PENGARAH KANAN (KESIHATAN PERGIGIAN) 3101010010 PEJABAT PENGARAH KANAN (PERKHIDMATAN FARMASI) 3101010011 PEJABAT PENGARAH KANAN (KESELAMATAN DAN KUALITI MAKANAN) 3101010012 BAHAGIAN AKAUN 3101010028 BAHAGIAN AMALAN DAN PERKEMBANGAN FARMASI 3101010047 BAHAGIAN AMALAN DAN PERKEMBANGAN KESIHATAN PERGIGIAN 3101010042 BAHAGIAN AMALAN PERUBATAN 3101010036 BAHAGIAN DASAR DAN HUBUNGAN ANTARABANGSA 3101010019 BAHAGIAN DASAR DAN PERANCANGAN STRATEGIK FARMASI 3101010050 BAHAGIAN DASAR DAN PERANCANGAN STRATEGIK KESIHATAN PERGIGIAN 3101010043 BAHAGIAN DASAR PERANCANGAN STRATEGIK DAN STANDARD CODEX 3101010054 BAHAGIAN KAWALAN PENYAKIT 3101010030 BAHAGIAN KAWALAN PERALATAN PERUBATAN 3101010055 BAHAGIAN KAWALSELIA RADIASI PERUBATAN 3101010041 BAHAGIAN KEJURURAWATAN 3101010035 BAHAGIAN KEWANGAN 3101010026 BAHAGIAN KHIDMAT PENGURUSAN 3101010023 BAHAGIAN PEMAKANAN 3101010033 BAHAGIAN PEMATUHAN DAN PEMBANGUNAN INDUSTRI 3101010053 BAHAGIAN PEMBANGUNAN 3101010020 BAHAGIAN PEMBANGUNAN KESIHATAN KELUARGA 3101010029 BAHAGIAN -

Kinta Valley, Perak, Malaysia

Geological Society of Malaysia c/o Department of Geology University of Malaya, 50603 Kuala Lumpur +603-79577036 (voice) +603-79563900 (fax) [email protected] http://www.gsm.org.my/ PERSATUAN GEOLOGI MALAYSIA GEOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF MALAYSIA COUNCIL 2013-2014 PRESIDENT : PROF. DR. JOY JACQUELINE PEREIRA (UKM) VICE-PRESIDENT : DR. MAZLAN MADON (PETRONAS) IMM. PAST PRESIDENT : DATO’ YUNUS ABDUL RAZAK (JMG) SECRETARY : MR. LING NAN LEY (JMG) ASSISTANT SECRETARY : MR. LIM CHOUN SIAN (UKM) TREASURER : MR. AHMAD NIZAM HASAN (GEOSOLUTION RESOURCES) EDITOR : ASSOCIATE PROF. DR. NG THAM FATT (UM) COUNCILLORS : MR. TAN BOON KONG (CONSULTANT) DR. NUR ISKANDAR TAIB (UM) DR. TANOT UNJAH (UKM) DR. SAMSUDIN HJ TAIB (UM) DR. MEOR HAKIF AMIR HASSAN (UM) MR. ROBERT WONG (PETRONAS) MR. NICHOLAS JACOB (JKR) MR. ASKURY ABD KADIR (UTP)* NATIONAL GEOSCIENCE CONFERENCE 2013 ORGANIZING COMMITTEE CHAIRMAN : DR. KAMALUDIN B. HASSAN (JMG PERAK) TECHNICAL CHAIRMAN : MR. HJ. ASKURY B. ABD. KADIR (UTP) TREASURER : MR. AHMAD NIZAM B. HASAN (GSM) SECRETARY/MEDIA : MS SUZANNAH BT AKMAL (JMG PERAK) ASST. SECRETARY : MR. MOHD. SHAHRIZAL B. MOHAMED SHARIFODIN (JMG PERAK) REGISTRATION : MR. LING NAN LEY (GSM) MS ANNA LEE (GSM) PRE-CONFERENCE FIELDTRIP AND : MR. HAJI ISMAIL B. IMAN (JMG PERAK) SPOUSE PROGRAM SPONSORSHIPS : MR AHMAD ZUKNI B. AHMAD KHALIL (JMG MALAYSIA) TEXT FOR SPEECHES : TUAN RUSLI B. TUAN MOHAMED (JMG PERAK) HOTEL AND ACCOMODATION : MR. MOHAMAD SARI B. HASAN (JMG PERAK) PROTOCOL AND SOUVENIRS : MS. MARLINDA BT DAUD (JMG MALAYSIA) COMMITTEE MEMBERS : MR. YUSNIN B. ZAINAL ABIDIN (IPOH CITY COUNCIL) MR SAW LID HAW (PERAK QUARRIES ASSOC.) PPeerrssaattuuaann GGeeoollooggii MMaallaayyssiiaa GGeeoollooggiiccaall SSoocciieettyy ooff MMaallaayyssiiaa PPrroocceeeeddiinnggss ooff tthhee NNAATTIIOONNAALL GGEEOOSSCCIIEENNCCEE CCOONNFFEERREENNCCEE 22001133 Kinta Riverfront Hotel and Suites, Ipoh 8-9th June 2013 Edited by: Nur Iskandar Taib Co-organizers: Copyright: Geological Society of Malaysia, 2013-05-29 All rights reserved. -

No. Name Address City Postcod State Country Off. No. Email 1 JING

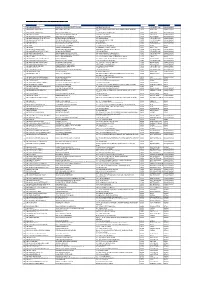

No. Name Address City Postcod State Country Off. No. Email [email protected] JING SHENG BG-16, JALAN MESTIKA / 1 CONSTRUCTION & CHERAS 56100 SELANGOR MALAYSIA 342957713 17, TAMAN MESTIKA [email protected] ENGINEERING SDN BHD om 2H OFFSHORE SUITE 16-3, 16TH FLOOR, KUALA WIL PER 2 50450 MALAYSIA 60321627500 [email protected] ENGINEERING SDN BHD WISMA UOA II, 21 JALAN LUMPUR K.LUMPUR LEVEL 8, BLOCK F, OASIS 3 3M MALAYSIA SDN BHD PETALING JAYA 47301 SELANGOR MALAYSIA 03-78842888 SQUARE, NO. 2, JALAN LOT 15 & 19, PERSIARAN NEG. 4 3M SEREMBA SEREMBAN 70450 MALAYSIA 66778111 TANJUNG 2, SENAWANG SEMBILAN PLO 317, JALAN PERAK, PASIR 072521288 / schw@5e- 5 5E RESOURCES SDN BHD 81700 JOHOR MALAYSIA KAWASAN GUDANG 072521388 resources.com 17-6, THE BOULEVARD KUALA WIL PER 6 8 EDUCATION SDN BHD 59200 MALAYSIA 03-22018089 OFFICE, MID VALLEY LUMPUR K.LUMPUR A & D DESIGN NETWORK F-10-3, BAY AVENUE PULAU 7 BAYAN LEPAS 11900 MALAYSIA 46447718 [email protected] SDN BHD LORONG BAYAN INDAH 1 PINANG NO 23-A, TINGKAT 1, 8 A & K TAX CONSULTANTS JALAN PEMBANGUNAN JOHOR BAHRU 81200 JOHOR MALAYSIA 72385635 OFF JALAN TAMPOI 9 A + PGRP 36B, SAGO STREET SINGAPORE 50927 SINGAPORE SINGAPORE 656325866 [email protected] A A DESIGN 390-A, JALAN PASIR 10 IPOH 31650 PERAK MALAYSIA 6052537518 COMMUNICATION SDN PUTEH, A H T (NORLAN UNITED) & BLOK B UNIT 4-8 IMPIAN KUALA WIL PER 11 50460 MALAYSIA 322722171 CARRIAGE SDN BHD KOTA, JALAN KAMPUNG LUMPUR K.LUMPUR A JALIL & CO SDN BHD ( IPOH ) NO. 14B, LALUAN IPOH 31350 PERAK MALAYSIA 05-3132072 MEDAH RAPAT, 12 A JALIL & CO SDN BHD GUNUNG RAPAT, NO. -

Shell Lebih Ekstra at Zalora Promotion Participating Stations List NO SITE

Shell Lebih Ekstra at Zalora Promotion Participating Stations List NO SITE NAME STATION NAME ADDRESS POSCODE CITY STATE 1 SH JALAN JELUTONG BAN LEONG SHELL PRODUCTS SDN BHD 347 JELUTONG ROAD 11600 GEORGETOWN PULAU PINANG 2 SH BANDAR AYER ITAM 2 BBAI SHELL SERVICES LOT 2499 JALAN THEAN TEIK, JALAN SHAIK MADAR BANDAR 11500 AYER ITAM PULAU PINANG BARU 3 SH BANDAR AYER ITAM 1 BBAI SALES & SERVICES 12 ANGSANA FARLIM ROAD 11500 AYER ITAM PULAU PINANG 4 SH BUKIT GELUGOR BUKIT GLUGOR SERVICE STATION 210 BUKIT GELUGOR 11700 GELUGOR PULAU PINANG 5 SH JLN MAYANG PASIR BAYAN BARU CERGAS SAUJANA SDN BHD JALAN MAYANG PASIR 11950 BAYAN BARU PULAU PINANG 6 SH JALAN BURMAH GEORGE TOWN ELITEBAY EXPRESS ENTERPRISE 378 JALAN BURMA 10350 GEORGETOWN PULAU PINANG 7 SH JALAN MESJID NEGERI GREEN ISLAND SERVICE STATION 4A JALAN MASJID NEGERI 11600 GEORGETOWN PULAU PINANG 8 SH BALIK PULAU KEAN YOON FATT FILLING STATION 315 GENTING 11000 BALIK PULAU PULAU PINANG 9 SH WELD QUAY LEAN HONG CO SDN BHD 30 WELD QUAY 10300 GEORGETOWN PULAU PINANG 10 SH GERIK MAESTRO ONE ENTERPRISE 122 JLN SULTAN ISKANDAR 33300 GERIK PERAK 11 SH LAWIN MEERA AAZ ENTERPRISE 2B KAMPUNG MALAU, LAWIN 33410 LENGGONG PERAK 12 SH JELUTONG EXPRESSWAY MILYAR MUTIARA ENTERPRISE LEBUHRAYA TUN DR LIM CHONG EU 11600 GEORGETOWN PULAU PINANG 13 SH JALAN PERAK GEORGE TOWN MS MASHA ENTERPRISE 190 JALAN PERAK 10150 GEORGETOWN PULAU PINANG 14 SH JALAN KELAWEI BIRCH MUKAH HEAD SERVICE STATION 2A JALAN KELEWAI / JALAN BIRCH 10250 GEORGETOWN PULAU PINANG 15 SH JALAN PAYA TERUBONG PAYA TERUBONG SERVICE STATION -

Asphaltic Concrete on Roads in Malaysia: Is Quality Under Control?

ASPHALTIC CONCRETE ON ROADS IN MALAYSIA: IS QUALITY UNDER CONTROL? Hanani Mohd Radzi Public Work Department Malaysia E-mail: [email protected] Mohd Hizam Harun Public Work Department Malaysia E-mail: [email protected] Wan Radhiah Wan Hanafi Public Work Department Malaysia E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT The introduction of asphaltic concrete in Malaysia has brought with it the problem of a through design process of the mixture composition and subsequent extensive control testing that are required to produce and lay the mixture to the required tolerances. However, it is unfortunate to note that many elements of the design, production and construction of the delicate mixture have been either blatantly ignored or manipulated by the contractors and the supervising consultants. While it is clearly stated in PWD guidelines that the initiation and execution of quality control testing must be not left to the contractor, it is a common practice in Malaysia to let the contractor carry out most or all the testing as a means to control the quality of the materials and construction works. Verification of test results by the supervising consultants is usually done on the basis of more or less effective surveillance, often by site staff with little or no training and experience. As such, PWD is invariably presented with inferior quality of materials and constructed works which include asphaltic concrete as road surfacing material. A total of 21 work sites were surveyed to identify the problems at each site. This paper looks into the problems and suggests ways how they could be mitigated. -

NEGERI PPD KOD SEKOLAH NAMA SEKOLAH ALAMAT BANDAR POSKOD TELEFON FAX Muat Turun Soalan Dan Skema PERCUMA PMR, SPM, STPM Dari

SENARAI SEKOLAH MENENGAH NEGERI PAHANG KOD NEGERI PPD NAMA SEKOLAH ALAMAT BANDAR POSKOD TELEFON FAX SEKOLAH PAHANG PPD BENTONG CEA0014 SMK BENTONG KAMPUNG BENUS BENTONG 28700 092221163 092235081 PAHANG PPD BENTONG CEA0015 SMK(LKTP)KG SERTIK KG. SERTIK, KARAK, 28610 092320203 092318772 PAHANG PPD BENTONG CEA0053 SMK (FELDA) LURAH BILUT LURAH BILUT LURAH BILUT 28800 092301010 092377893 PAHANG PPD BENTONG CEA0055 SMK SERI PELANGAI KAMPUNG SIMPANG PELANGAI BENTONG 28740 092391141 092391325 PAHANG PPD BENTONG CEA0056 SMK SERI BENTONG KG. KARAK SETIA, KARAK 28600 092312161 092313331 JALAN LAMA BENTONG-KUALA LUMPUR, PAHANG PPD BENTONG CEA0057 SMK BUKIT TINGGI BENTONG 28750 092330684 092330684 BUKIT TINGGI, PAHANG PPD BENTONG CEA0058 SMK KUALA REPAS KM 5, JALAN TRAS BENTONG 28700 092228158 092201150 PAHANG PPD BENTONG CEA0059 SMK KARAK SETIA KAMPONG KARAK SETIA KARAK 28600 09-2320459 09-2311006 PAHANG PPD BENTONG CEA7136 SMK (FELDA) CHEMOMOI FELDA CHEMOMOI TRIANG 28310 092458393 092457352 PAHANG PPD BENTONG CEB0017 SMK TELEMONG KAMPUNG TELEMONG KARAK 28620 092399788 092399788 PAHANG PPD BENTONG CEB0019 SMK KETARI JALAN KUALA LUMPUR BENTONG 28700 092221278 092235571 PAHANG PPD BENTONG CEB0020 SMK KATHOLIK JALAN KETARI BENTONG 28700 092221505 092221505 PAHANG PPD BENTONG CEB0021 SMK KHAI MUN CHAMANG BARU BENTONG 28700 092221137 092223439 PAHANG PPD BENTONG CEE0016 SMK KARAK JALAN BESAR KARAK KARAK 28600 092312770 092313669 PAHANG PPD BENTONG CEE0018 SMK SULAIMAN KM 4, JALAN KUALA LUMPUR BENTONG 28700 092221046 092220200 PAHANG PPD BENTONG CHA0002 -

Radiometric Age of Kampung Awah Andesite

Geological Society of Malaysia, Bulletin 48 June 2004, p. 51 - 54 Radiometric age of Kampung Awah andesite WAN FUAD WAN HASSANl & HERU SIGIT PURWANT02 1 School of Environmental Science and Natural Resources, Faculty of Science and Technology Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, 43600 Bangi, Selangor Darul Ehsan 2 Geology Department, Faculty of Mineral Technology, University of National Development, Yogyakarta, Indonesia Abstract: The age of andesite from Kampung Awah in particular and the Peninsular Malaysia in general, is reported as Upper Permian. A sample from Kampung Awah andesite was sent for K-Ar radiometric dating. The result obtained is 269±46 Ma or Middle Permian age. The result indicates that contrary to earlier belief, the andesite of Kampung Awah was extruded earlier, viz. in Middle Permian and that limestone was subsequently deposited on the cooled andesite much later, in the Upper Permian period. An older age for the andesite is also supported by field and petrological evidences. Abstrak: Usia andesite Kampung Awah khususya dan bagi Semenanjung Malaysia umumnya dianggap sebagai Perm Atas. Suatu sampel andesit dari Kampung Awah telah di hantar untuk di buat penentuan usia secara radiometri K-Ar. Hasil diperolehi ialah usia 269±46 juta tahun atau Perm Tengah. Hasil ini menunjukkan, berbeza daripada pandangan lalu, bahawa andesit Kampung Awah menerobos ke permukaan lebih awal iaitu pada Perm Tengah, diikuti kemudian dengan pengendapan batu kapur di atas andesit yang telah sejuk, pada Perm Atas. Usia lebih tua bagi andesit ini disokong oleh bukti-bukti lapangan dan juga petrologi. INTRODUCTION The Kampung Awah andesite quarry is a readily accessible locality well-known among local geologists.