Celebrating 30 Years

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Of·Minnesota

" . ::,UD.iversity of·Minnesota., . D'irectory ComprisiDg a comp~ 'list of the fac;~"ty.D'Y'::';:·":? ~ ',.t· .;::.£!-t~ :t~'~P1' a classified list ofstli"~"'r~H; '."'-~j deDt. with theirci.,n.;;;J~~. aDd home addresse.;:j:~;:ihr" • ~, < ~:?~ you thinking college man sooner or later . you are comIng here for good clothes. Hart Schaffner & Marx $18 10 and The "L System" $50 MiDDeapolio St. Paul a.icaao / SPECIAL DISCOUNTS TO STUDENTS MOREN TAILOR NICOLLET AVENUE 6 2 5 623 SHOE·MART BUILDING Moran-Peterson Co. TaIlors· Nicollet Avenue at Seventh Entrance to store 6201/2 Nicollet Ask your inspection of their . recent Importations for Fall and Winter nineteen hundred and ten Respectfully Moran -'Peterson Co. 1 -, I 'Ve are the 2\Ianufacturers' Distributors of high-grade artistic Pianos, Organs and Player-Pianos. We want agencies and dealers In every part of the country to selI or take orders for our Pianos at your home or place of business. Big profits. 'Vrite for territory, catalogues. wholesale prices, terms and special agency proposition on a sample Piano. CalI at our store If convenient. Priess Piano Co. 1025 Hennepin An'., !I1nnenpoU", !I1nn. NEW STUDENTS, ATTENTION! DORSETT THE UNIVERSITY CATERER Furnishes the best of everything in the line of Eatahlt>s, China, Silvt>r, Damask, Servants and Tables for Banquets. Manufacturer of Dt>licious Frozen Creams, Fruit Ices and Frappes. Phone in your orders. 51 South Eighth SU'eet X. 'Y., Main 3264-·TELEPHONES-T.-S., Center 3952 An Ideal Hall for Dancing The TEA ROOM caters to Evening Functions given in the hall, in addition to the usual daily service Simple or elaborate menus. -

Geschichte Neuerwerbungsliste 3. Quartal 2010

Geschichte Neuerwerbungsliste 3. Quartal 2010 Geschichtsschreibung und Geschichtstheorie ..........................................................................................................2 Teilbereiche der Geschichte (Politische Geschichte, Kultur-, Sozial- und Wirtschaftsgeschichte allgemein) ........5 Historische Hilfswissenschaften ..............................................................................................................................9 Ur- und Frühgeschichte; Mittelalter- und Neuzeitarchäologie...............................................................................10 Allgemeine Weltgeschichte, Geschichte der Entdeckungen, Geschichte der Weltkriege......................................19 Alte Geschichte......................................................................................................................................................31 Europäische Geschichte in Mittelalter und Neuzeit ...............................................................................................33 Deutsche Geschichte..............................................................................................................................................36 Geschichte der deutschen Laender und Staedte .....................................................................................................46 Geschichte der Schweiz, Österreichs, Ungarns, Tschechiens und der Slowakei ...................................................54 Geschichte Skandinaviens......................................................................................................................................57 -

*RMINL Spring02.Cb11.3.01

Rocky Mountain Institute/volume xviii #1/Spring 2002 newsletterRMIRMISolutionsSolutions TIME FOR A SWITCH RMI Helps Reframe U.S. Energy Policy At Airlie House in Warrenton, Virginia, on 1–3 February, RMI convened two dozen of America’s most distinguished and thoughtful energy experts from the private and public sectors (but not including advo- cacy groups or serving public officials). Their deep experience embraced all energy sectors and phases—supply, delivery, con- sumption, technology, R&D, competition, and regulation. These politically diverse luminaries came NEP Initiative facilitator Larry Susskind, far right, leads the Expert Group together to rethink U.S. energy policy at a through a discussion of transportation. Photos: Norm Clasen time when Congressional debate has become so polarized that agreement on By Cameron M. Burns but-narrow constituencies promoting their favorite energy technologies. Largely absent continued on next page hat kind of world are we is a clear sense of what nearly everyone leaving for our children, agrees about, and how to incorporate those Wgrandchildren, and great- consensus elements into a balanced port- grandchildren? Will it be better, safer, and folio that can deliver to the American CONTENTS fairer? And will U.S. energy policy help get people (and help to deliver to all people us there? everywhere) desired energy services in SUSTAINABLE SETTLEMENTS ....page 4 Today, all but the terminally uninformed ways that are secure, reliable, healthful, MAYOR BROWN INTERVIEW .....page 8 realize that the number -

Boston Nature Center Welcomes All

Boston Nature Center Welcomes All 2018 Annual Report Dear BNC Community, Recognizing that diversity is as important in organi- zational culture as it is in nature, a central priority of Mass Audubon’s strategic plan is ensuring that we share the gift of connection to nature with the broadest group of people, and do it in ways that are most meaningful to them. As an urban sanctu- ary nestled within some of Boston’s most diverse neighborhoods, Boston Nature Center enjoys unique opportunities to explore and practice ways of being welcoming. This imperative informs much of what we do and how we do it. To amplify the reach of our programs, Boston Nature Center (BNC) partners with the Boston ask their friend which pronoun they prefer. Individu- Public Schools, Head Start programs, and home als who have sensory challenges will find that we school groups to infuse their curricula with hands- have a trail just for them, and that our green build- on, minds-on science, technology, engineering, and ing is also fully accessible. Many of our staff mem- math (STEM). We offer community members of all bers are bilingual and our sanctuary guides are ages a wide variety of high quality, engaging, and available in Spanish and Braille. Our numerous affordable programs, especially during the summer, volunteer groups include participants who attend that meet the needs of working families and keep adult day programs. urban young people learning and growing all year long. Our three-year environmental internship We hope that you will find yourself here at the BNC. -

Mysticism and Emotional Transformation in a Seventeenth-Century English Convent

Mysticism and Emotional Transformation in a Seventeenth-Century English Convent By Jessica McCandless A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History, Faculty of Arts, University of Adelaide. July 2020 Declaration I certify that this work contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. In addition, I certify that no part of this work will, in the future, be used in a submission in my name, for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of the University of Adelaide. I acknowledge that copyright of published works contained within this thesis resides with the copyright holder(s) of those works. I also give permission for the digital version of my thesis to be made available on the web, via the University’s digital research repository, the Library Search and also through web search engines, unless permission has been granted by the University to restrict access for a period of time. I acknowledge the support I have received for my research through the provision of an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship. Signed _ ____ Date _29 June 2020_________ i Acknowledgements Above all, I wish to thank Dr Claire Walker. Her scholarly prowess, tireless support and, most importantly, warm friendship has shaped me as an academic and a person. -

MINUTES Board of City Commissioners August 10, 2021 | 6:00 Pm CT City Hall & Gotomeeting | Williston, North Dakota

MINUTES Board of City Commissioners August 10, 2021 | 6:00 pm CT City Hall & GoToMeeting | Williston, North Dakota 1. Roll Call of Commissioners and Pledge of Allegiance COMMISSIONERS PRESENT: Tate Cymbaluk, Chris Brostuen, Brad Bekkedahl, Deanette Piesik, Howard Klug COMMISSIONERS ABSENT: None OTHERS PRESENT: Shawn Wenko, Anthony Dudas, David Tuan, Andrea Placher, Kenny Bergstrom, Josilyn Bean, Rachel Laqua, Mark Schneider, Dave Peterson, Amy Krueger, Kent Jarcik, David Juma, Caitlin Pallai, Pete Furuseth Changes to Agenda: None Mayor Klug presented a quorum. Motion by Cymbaluk, Seconded by Brostuen to approve the consent agenda for August 10, 2021, as presented. UNANIMOUS BY VOICE VOTE 2. Consent Agenda A. Reading and Approval of Minutes 1) Regular Meeting – July 27, 2021 B. Auditor and Finance 1) Accounts, Claims and Bills – July 23-August 5, 2021 Check between 7/23/2021-08/05/2021 Check# Payee Amount Date Epay Minnesota Child Support $320.71 07/30/21 10880 ND State Tax Commissioner $370.80 07/30/21 10881 United States Treasury $440.00 07/30/21 10882 Christopher A. Carlson, P.C. $286.47 07/30/21 518802 WIEDRICH ALYSSA $1,543.38 07/30/21 518803 ELLICO BARBARA $1,833.20 07/30/21 518804 PALLAI CAITLIN $1,935.35 07/30/21 518805 PIERZINA CHERY $3,350.73 07/30/21 518806 TUAN DAVID $4,075.40 07/30/21 518807 BEAN JOSILYN $2,857.65 07/30/21 518808 BERGSTROM KENNETH $3,449.01 07/30/21 518809 DIXON KRISTIN $2,532.10 07/30/21 518810 MERRITT MIRANDA $1,582.19 07/30/21 518811 WIEDRICH OLIVIA $1,207.96 07/30/21 AUGUST 10, 2021 2 | PAGE VOTE TALLY 518812 MASTERS PEGGY $2,043.33 07/30/21 518813 DUDAS ANTHONY $3,683.81 07/30/21 518814 ATKINS CAMERON $1,443.03 07/30/21 518815 LINDVIG CORDELL $2,062.01 07/30/21 518816 WALKER DAMON $1,680.74 07/30/21 518817 REIFSTECK DEVIN $1,922.02 07/30/21 518818 MARSHALL GLENN $2,299.60 07/30/21 518819 BOYKIN KENNETH $2,340.92 07/30/21 518820 SPROUSE MICHAEL $2,169.44 07/30/21 518821 HANSON ROBERT S. -

Cardinal Weekend 2019 Operations, Management, and Global Visit Engage.Catholic.Edu

ALUMNI CORNER ALUMNI Class Notes CORNER Patricia Fogarty, B.A. 1971, J.D. 1950s 1974, has been elected to a three- year term on the board of trustees UPCOMING ALUMNI EVENTS Sister Laurette Bellamy, S.P., for Catholic Charities of Buffalo. M.M. 1955, celebrated her 70-year An Allegany County assistant jubilee as a member of the Sisters public defender and a longtime May 8: Senators Club of Providence. A native of Chicago, county resident, she has a long The Senators Club, an alumni networking and philanthropic she entered the congregation on history of civic activity and service group, will hold its annual luncheon on May 8. The Club, Feb. 2, 1948, and professed final on the boards of Allegany County founded in 1923 with 38 original members from what was vows on Aug. 15, 1955. She United Way and Southern Tier then the School of Engineering and Architecture, has expanded ministers as a volunteer at Our Traveling Teachers. over the years to welcome alumni from all schools within the Lady of the Greenwood Parish University. The group is now 300 members strong and sponsors in Greenwood, Ind. Carol Maillard, B.A. 1973, one the Senators Club Alumni Scholarship, which provides financial of the founding members of the assistance to full-time, undergraduate students seeking a degree African American female a cappella in the schools of architecture and planning, arts and sciences, or 1960s group Sweet Honey in the Rock, engineering. joined the ensemble as artists- The May 8 luncheon will begin at 11:30 a.m., followed by a Raymond Murphy, B.A. -

Dean's List—Spring 2019

DEAN’S LIST—SPRING 2019 David E. Abarca Skylar G. Brewer Brigitte Acevedo Jered J. Brown Corina Acevedo Meirabelle N. Brown Charmelle A. Agcaoili Derek Bryant Oluyemisi O. Akinbade Jessica M. Buchholtz Edwin E. Alarcon Kylah D. Bunch Lena J. Albright Kaylin J. Burge Cristina P. Alcala Anna M. Burris Rachael I. Alred Kaylie I. Calderon Haneen B. Alsarama Edgar Camarena Islam B. Alsarama Nicolas D. Campos Judith Ambriz John L. Capps Ashlynd C. Anderson Trista A. Capps Hunter L. Anderson Allyson B. Carothers Rebeca Antunez Wylie R. Carver Angel J. Aquino Rodolfo A. Casas-Vargas Carissa Aranda Meghan M. Case Zureyly Arellano Kevin R. Cassidy Analila Arias Corina J. Castillo Alexis D. Armijo Gabriela Castillo Kolby J. Arnold Imperia Castillo Isabella R. Arriaga Ariana L. Castro Alyssa L. Aucutt Maria G. Ceja Sydnee M. Averill Amy J. Cervine Jenelle B. Avery Alex Chacon-Vasquez Ricardo Ayala Shauntia N. Chapman Johanna J. Badillo Logan W. Chase Nuri Bahena Emily Chavez Adrian D. Banuelos Nakota R. Chavez Lupe V. Bazan Veronica Chavez Hannah R. Baze Xochitl Chavez Amy S. Beaumonte Rebecca L. Chester Joseph O. Becker Nora Cisneros Samantha A. Belton Caitlin E. Clark Rose Bender Patricia I. Clemmens Haley G. Benedetti Ruben Cohetzaltitla Kathrine B. Bennett Kaitlyn D. Cooper Serenity G. Benoit James D. Copeland Maria G. Bernal Coty A. Corral Venezza B. Bires Jorge L. Covarrubias Devin N. Bishop Jessica D. Cranefield Dustin C. Bishop Anthony D. Cromwell Harrison T. Blankenship Cierra B. Crowell Ben D. Bobeck Veronica L. Cruz-Juarez Raven C. Bolen Yasmin Cuellar Savannah J. Bonny Alexander T. -

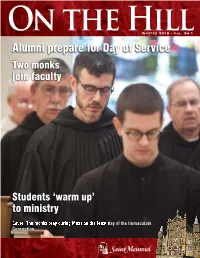

Alumni Prepare for Day of Service Two Monks Join Faculty

On the Hill Winter 2015 • Vol. 54:1 Alumni prepare for Day of Service Two monks join faculty Students ‘warm up’ to ministry Cover: The monks pray during Mass on the feast day of the Immaculate Conception. On the Hill Winter 2015 • Vol. 54:1 FEATURES 3 . .Monastery News 4-5 . .Project WARM 6 . .Student Profile 8 . .Faculty Books 9 . .New Saint Meinrad Tour App 10-11 . .Photos ALUMNI 12 . .Saint Meinrad Day of Service 14-15 . .Alumni Eternal and News 16 . .Alumni Reunion On the Hill is published four times a year by Saint Meinrad Archabbey and Seminary and School of Theology. The newsletter is also available online at: www.saintmeinrad.edu/onthehill Editor: . .Mary Jeanne Schumacher Copywriters: . .Krista Hall & Tammy Schuetter Send changes of address and comments to: The Editor, The Development Office, Saint Meinrad Archabbey and Seminary & School of Theology, 200 Seminarians and President-Rector Fr. Denis Robinson, OSB, present a Hill Drive, St. Meinrad, IN 47577, (812) 357-6501 • Fax (812) 357-6759, [email protected] skit during the St. Nicholas Banquet in December. www.saintmeinrad.edu, © 2015, Saint Meinrad Archabbey For more photos of events on the Hill, see… Pg. 10-11 Monks’ Personals Fr. Tobias Colgan and Fr. Denis Archabbot Justin DuVall traveled to of the monastic continuing formation Robinson attended the 10th anniversary St. Joseph Abbey in Covington, LA, to programs offered at Sant Anselmo, celebration at Bishop Simon Bruté take part in the celebration of its 125th Rome. Seminary in Indianapolis, IN, in anniversary. mid-September. Br. Francis Wagner has been appointed Fr. -

Mission and Ecstasy: Contemplative Women and Salvation in Colonial Spanish America and the Philippines

STUDIA MISSIONALIA SVECANA CXV Magnus Lundberg Mission and Ecstasy Contemplative Women and Salvation in Colonial Spanish America and the Philippines Lundberg, Magnus. Mission and Ecstasy: Contemplative Women and Salvation in Colonial Spanish America and the Philippines. Studia Missionalia Svecana 115. 264 pp. Uppsala: Swedish Institute of Mission Research, 2015. Author’s address: Magnus Lundberg, Uppsala university, Department of Theology, Box 511, SE-751 20 Uppsala, Sweden. E-mail: [email protected] © Magnus Lundberg 2015 ISSN 1404-9503 ISBN 978-91-506-2443-4 http://uu.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2%3A790056&dswid=-3689 The printing of this book was made possible by a grant from Riksbankens Jubileumsfond (The Bank of Sweden Tercentenary Foundation). Cover image: Mariana de Jesús (1618-1645), wooden statue, Quito, Ecuador. Photo: Towe Wandegren, 2013. Printed in Sweden by DanagårdLITHO AB, 2015. Contents Preface ............................................................................................................ 5 Introduction ..................................................................................................... 7 Texts .............................................................................................................. 35 Ideals ............................................................................................................. 47 Love .............................................................................................................. 67 Prayer ........................................................................................................... -

Air Force's Personnel Center

AIR FORCE'S PERSONNEL CENTER 19E5 Staff Sergeant Worldwide Selects List Alphabetical by Last Name (*List excludes Intel, ISR, OSI AFSCs) For Public Release August 22, 2019 NAME AARDEMA JARED EUGE ABBAS ABBAS ABDULR ABBOTT DESHAWN MAR ABBOTT ZACHARY JOH ABBRUZZESE MICHAEL ABDULKAREEM RASHAD ABEL DAMON JEROME ABEL FRANCIS BRY ABEL MATTHEW BLAKE ABEL MATTHEW SCOTT ABELL TYLER THOMAS ABELL ZACHARY RYAN ABELRIVERA WILLIAM ABERNATHY JAMES A ABEYTA JAMIN MICHE ABEYTA TAYLOR KING ABITZ JOHN ISAAC ABLANG JEREMY GABR ABLES CASEY LYNNE ABNEY PHILLIP RYAN ABOAGYEWAA EUNICE ABRAHAM AARON MARK ABREGO ANDRES JULI ABRIL DANNYSON PAD ABSHIRE TRENT DEAN ACERO BRANDON MART ACEVEDO ARTHUR JR ACEVEDO BETANCOURT ACEVEDO DESIREE DA ACEVEDO RODRIGUEZ ACHUFF GABRIELLE D ACKERSON SABRINA L AIR FORCE'S PERSONNEL CENTER ACOSTA ARNIDA MARI ACOSTA CONSUELO CA ACOSTA JESSICA JOS ACOSTA JOSE ANTONI ACOSTA STACY ACRA JONATHAN WADI ACREE TREVOR WADE ACUESTA CHARLES VI ACUNA RAFAEL TRIAN ACUNA TELLEZ JESUS ADAM PEREZ JAICEL ADAME MIGUEL ADAMS AQUILAS DOS ADAMS BLAKE SPENCE ADAMS CALUM ALEXAN ADAMS CARTER AMBER ADAMS CHYEANNE LEI ADAMS CONNER AUSTI ADAMS EBONY NICOLE ADAMS JARED ANDREW ADAMS JARED CADEL ADAMS JEREMY JAMES ADAMS JOSHUA JAMES ADAMS KALA ALEXAND ADAMS KELSEY REED ADAMS KHADIJAH AMI ADAMS KYLE D ADAMS LOGAN WAYNE ADAMS NICHOLAS BRA ADAMS PETER DAVID ADAMS PHILLIP ANDR ADAMS TIMOTHY JOSH ADAMS TODD ALAKAI ADANSI PIPIM KOFI ADCOCK ERNEST JACO ADCOCK KARISA LYNN ADCOCK MATTHEW JOS ADDAE KEVIN KWADWO ADDERLEY SERGIO AL ADDERTONENRIGHT DA ADDISON JORDAN TYL AIR -

All-Time Nw District State Placewinners – 2019 Ada

ALL-TIME NW DISTRICT STATE PLACEWINNERS – 2019 Vuong Nguyen, Division III 6 th place, 103 pounds, 1989 ADA Tyler Weirauch, Diviion III 7 th place, 119 pounds, 2006 Austin Windle, Division III 7th place, 160 pounds, 2014 Austin Ripke, Division III 7 th place, 160 pounds, 2012 Chase Sumner, Division III 4 th place, 132 pounds, 2016 T.J. Weiruach, Division III 8 th place, 125 pounds, 2011 Chase Sumner, Division III 7 th place, 145 pounds, 2018 Drew Coffey, Division III 8 th place, 106 pounds, 2012 Chase Sumner, Division III 8 th place, 138 pounds, 2017 Gavin Grime, 8 th place, Division III, 132 pounds, 2017 Colton Soles, Division III 8 th place, 152 pounds, 2018 ANTWERP Aidan McAlexander, Divlsion III 3rd place, 106 pounds, 2018 ASHLAND Wyatt Music, Division I State Champ, 145 pounds, 2013 ARCADIA Josh Bever, Division I State Champ, 220 pounds, 2019 Jeff Crow, Class A State Champ, 155 pounds, 1978 Sid Ohl, Division II, 2 nd place, 152 pounds, 2017 Brian Brooks, Class A State Champ, 175 pounds, 1981 Toby Kerschner, Division I 3rd place, 275 pounds, 1995 Steve True, Class A 2 nd place, 145 pounds, 1977 Clell Cox, Division I 3rd place, 189 pounds, 1997 Fred Noel, Class A 2 nd place, 98 pounds, 1982 Ben Householder, Division I 3rd place, 215 pounds, 1999 Dusty Wilson, Class A 2 nd place, 145 pounds, 1986 Zach Andy, Division I 3rd place, 189 pounds, 2002 Roger Weaver, Class A 3 rd place, HWT, 1978 Gary Russell, No Division 4th place, 165 pounds, 1968 Lee Schumaker, Division III 3 rd place, 130 pounds, 2007 Brent Weisenstein, Division I 4 th place,