Indice Dei NOMI - VOLUME I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Evaluation of the Phylogenetic Relationships of the Pterosaurs Among Archosauromorph Reptiles

Journal of Systematic Palaeontology 5 (4): 465–469 Issued 19 November 2007 doi:10.1017/S1477201907002064 Printed in the United Kingdom C The Natural History Museum An evaluation of the phylogenetic relationships of the pterosaurs among archosauromorph reptiles David W. E. Hone∗ Department of Earth Sciences, University of Bristol, Queens Road, Bristol, BS8 1RJ, UK Michael J. Benton Department of Earth Sciences, University of Bristol, Queens Road, Bristol, BS8 1RJ, UK SYNOPSIS The phylogenetic position of pterosaurs among the diapsids has long been a contentious issue. Some recent phylogenetic analyses have deepened the controversy by drawing the pterosaurs down the diapsid tree from their generally recognised position as the sister group of the dinosaur- omorphs, to lie close to the base of Archosauria or to be the sister group of the protorosaurs. Critical evaluation of the analyses that produced these results suggests that the orthodox position retains far greater support and no close link can be established between pterosaurs and protorosaurs. KEY WORDS Pterosauria, Prolacertiformes, Archosauria, Archosauromorpha, Ornithodira Contents Introduction 465 Methods and Results 466 Discussion 467 Re-analysis of Bennett (1996) 467 Re-analysis of Peters (2000) 467 Conclusions 469 Acknowledgements 469 References 469 Introduction tained). Muller¨ (2003, 2004) also suggested that the prolacer- tiforms were not a valid clade, with Trilophosaurus splitting The basal archosaurs and their phylogenetic positions relative his two prolacertiform taxa (Prolacerta and Tanystropheus). to one another within the larger clade Archosauromorpha The analysis performed by Senter (2004) also found the pro- have been a source of controversy among palaeontologists lacertiforms to be paraphyletic, although here he removed the for decades. -

Paleocene Mammalian Faunas of the Bison Basin in South-Central Wyoming

SMITHSONIAN MISCELLANEOUS COLLECTIONS VOLUME 131, NUMBER 6 Cftarlesi ©, anb JHarp ^aux SKHalcott 3Res!earcf) Jf unb PALEOCENE MAMMALIAN FAUNAS OF THE BISON BASIN IN SOUTH-CENTRAL WYOMING (With 16 Plates) By C. LEWIS GAZIN Curator, Division of Vertebrate Paleontology United States National Museum Smithsonian Institution (Publication 4229) CITY OF WASHINGTON PUBLISHED BY THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION FEBRUARY 28, 1956 THE LORD BALTIMORE PRESS, INC. BALTIMORE, MD., U. S. A. CONTENTS Page Introduction i Acknowledgments 2 History of investigation 2 Occurrence and preservation of material 3 The Bison basin faunas 4 Environment and relationships between the Bison basin faunas 7 Age and correlation of the faunas lo Systematic description of vertebrate remains I2 Reptilia 12 Sauria 12 Anguidae 12 Mammalia 12 Multitubcrculata 12 Ptilodontidae 12 Marsupialia 14 Didelphidae 14 Insectivora 15 Leptictidae 15 Pantolestidae 17 Primates 19 Plesiadapidae 19 Carnivora 25 Arctocyonidae 25 Mesonychidae 35 Miacidae 35 Condylarthra 36 Hyopsodontidae 36 Phenacodontidae 42 Pantodonta 47 Coryphodontidae 47 References 51 Explanation of plates 54 ILLUSTRATIONS Plates (All plates following page 58.) 1. Mullituberculates and insectivores from the Bison basin Paleocene. 2. Primates and marsupials from the Bison basin Paleocene. 3. Pronothodcctes from the Bison basin Paleocene. 4. Plcsiadapis from the Bison basin Paleocene. 5. Triccntcs and Chriacus from the Bison basin Paleocene. 6. Thryptacodon from the Bison basin Paleocene. 7. Clacnodon from the Bison basin Paleocene. 8. Litomylus and Protoselcnc? from the Bison basin Paleocene. 9. Haplaletes and Gidleyina from the Bison basin Paleocene. 10. Phcnacodusl from the Bison basin Paleocene. 11. Condylarths and Titanoidcs from the Bison basin Paleocene. 12. Caenolambda from the Bison basin Paleocene. -

Chapter 2 Paleozoic Stratigraphy of the Grand Canyon

CHAPTER 2 PALEOZOIC STRATIGRAPHY OF THE GRAND CANYON PAIGE KERCHER INTRODUCTION The Paleozoic Era of the Phanerozoic Eon is defined as the time between 542 and 251 million years before the present (ICS 2010). The Paleozoic Era began with the evolution of most major animal phyla present today, sparked by the novel adaptation of skeletal hard parts. Organisms continued to diversify throughout the Paleozoic into increasingly adaptive and complex life forms, including the first vertebrates, terrestrial plants and animals, forests and seed plants, reptiles, and flying insects. Vast coal swamps covered much of mid- to low-latitude continental environments in the late Paleozoic as the supercontinent Pangaea began to amalgamate. The hardiest taxa survived the multiple global glaciations and mass extinctions that have come to define major time boundaries of this era. Paleozoic North America existed primarily at mid to low latitudes and experienced multiple major orogenies and continental collisions. For much of the Paleozoic, North America’s southwestern margin ran through Nevada and Arizona – California did not yet exist (Appendix B). The flat-lying Paleozoic rocks of the Grand Canyon, though incomplete, form a record of a continental margin repeatedly inundated and vacated by shallow seas (Appendix A). IMPORTANT STRATIGRAPHIC PRINCIPLES AND CONCEPTS • Principle of Original Horizontality – In most cases, depositional processes produce flat-lying sedimentary layers. Notable exceptions include blanketing ash sheets, and cross-stratification developed on sloped surfaces. • Principle of Superposition – In an undisturbed sequence, older strata lie below younger strata; a package of sedimentary layers youngs upward. • Principle of Lateral Continuity – A layer of sediment extends laterally in all directions until it naturally pinches out or abuts the walls of its confining basin. -

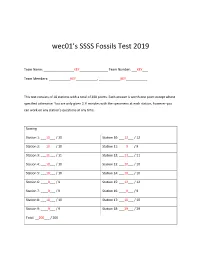

Wec01's SSSS Fossils Test 2019

wec01’s SSSS Fossils Test 2019 Team Name: _________________KEY________________ Team Number: ___KEY___ Team Members: ____________KEY____________, ____________KEY____________ This test consists of 18 stations with a total of 200 points. Each answer is worth one point except where specified otherwise. You are only given 2 ½ minutes with the specimens at each station, however you can work on any station’s questions at any time. Scoring Station 1: ___10___ / 10 Station 10: ___12___ / 12 Station 2: ___10___ / 10 Station 11: ____9___ / 9 Station 3: ___11___ / 11 Station 12: ___11___ / 11 Station 4: ___10___ / 10 Station 13: ___10___ / 10 Station 5: ___10___ / 10 Station 14: ___10___ / 10 Station 6: ____9___ / 9 Station 15: ___12___ / 12 Station 7: ____9___ / 9 Station 16: ____9___ / 9 Station 8: ___10___ / 10 Station 17: ___10___ / 10 Station 9: ____9___ / 9 Station 18: ___29___ / 29 Total: __200___ / 200 Team Number: _KEY_ Station 1: Dinosaurs (10 pt) 1. Identify the genus of specimen A Tyrannosaurus (1 pt) 2. Identify the genus of specimen B Stegosaurus (1 pt) 3. Identify the genus of specimen C Allosaurus (1 pt) 4. Which specimen(s) (A, B, or C) are A, C (1 pt) Saurischians? 5. Which two specimens (A, B, or C) lived at B, C (1 pt) the same time? 6. Identify the genus of specimen D Velociraptor (1 pt) 7. Identify the genus of specimen E Coelophysis (1 pt) 8. Which specimen (D or E) is commonly E (1 pt) found in Ghost Ranch, New Mexico? 9. Which specimen (A, B, C, D, or E) would D (1 pt) specimen F have been found on? 10. -

Reptile Family Tree

Reptile Family Tree - Peters 2015 Distribution of Scales, Scutes, Hair and Feathers Fish scales 100 Ichthyostega Eldeceeon 1990.7.1 Pederpes 91 Eldeceeon holotype Gephyrostegus watsoni Eryops 67 Solenodonsaurus 87 Proterogyrinus 85 100 Chroniosaurus Eoherpeton 94 72 Chroniosaurus PIN3585/124 98 Seymouria Chroniosuchus Kotlassia 58 94 Westlothiana Casineria Utegenia 84 Brouffia 95 78 Amphibamus 71 93 77 Coelostegus Cacops Paleothyris Adelospondylus 91 78 82 99 Hylonomus 100 Brachydectes Protorothyris MCZ1532 Eocaecilia 95 91 Protorothyris CM 8617 77 95 Doleserpeton 98 Gerobatrachus Protorothyris MCZ 2149 Rana 86 52 Microbrachis 92 Elliotsmithia Pantylus 93 Apsisaurus 83 92 Anthracodromeus 84 85 Aerosaurus 95 85 Utaherpeton 82 Varanodon 95 Tuditanus 91 98 61 90 Eoserpeton Varanops Diplocaulus Varanosaurus FMNH PR 1760 88 100 Sauropleura Varanosaurus BSPHM 1901 XV20 78 Ptyonius 98 89 Archaeothyris Scincosaurus 77 84 Ophiacodon 95 Micraroter 79 98 Batropetes Rhynchonkos Cutleria 59 Nikkasaurus 95 54 Biarmosuchus Silvanerpeton 72 Titanophoneus Gephyrostegeus bohemicus 96 Procynosuchus 68 100 Megazostrodon Mammal 88 Homo sapiens 100 66 Stenocybus hair 91 94 IVPP V18117 69 Galechirus 69 97 62 Suminia Niaftasuchus 65 Microurania 98 Urumqia 91 Bruktererpeton 65 IVPP V 18120 85 Venjukovia 98 100 Thuringothyris MNG 7729 Thuringothyris MNG 10183 100 Eodicynodon Dicynodon 91 Cephalerpeton 54 Reiszorhinus Haptodus 62 Concordia KUVP 8702a 95 59 Ianthasaurus 87 87 Concordia KUVP 96/95 85 Edaphosaurus Romeria primus 87 Glaucosaurus Romeria texana Secodontosaurus -

HOVASAURUS BOULEI, an AQUATIC EOSUCHIAN from the UPPER PERMIAN of MADAGASCAR by P.J

99 Palaeont. afr., 24 (1981) HOVASAURUS BOULEI, AN AQUATIC EOSUCHIAN FROM THE UPPER PERMIAN OF MADAGASCAR by P.J. Currie Provincial Museum ofAlberta, Edmonton, Alberta, T5N OM6, Canada ABSTRACT HovasauTUs is the most specialized of four known genera of tangasaurid eosuchians, and is the most common vertebrate recovered from the Lower Sakamena Formation (Upper Per mian, Dzulfia n Standard Stage) of Madagascar. The tail is more than double the snout-vent length, and would have been used as a powerful swimming appendage. Ribs are pachyostotic in large animals. The pectoral girdle is low, but massively developed ventrally. The front limb would have been used for swimming and for direction control when swimming. Copious amounts of pebbles were swallowed for ballast. The hind limbs would have been efficient for terrestrial locomotion at maturity. The presence of long growth series for Ho vasaurus and the more terrestrial tan~saurid ThadeosauTUs presents a unique opportunity to study differences in growth strategies in two closely related Permian genera. At birth, the limbs were relatively much shorter in Ho vasaurus, but because of differences in growth rates, the limbs of Thadeosau rus are relatively shorter at maturity. It is suggested that immature specimens of Ho vasauTUs spent most of their time in the water, whereas adults spent more time on land for mating, lay ing eggs and/or range dispersal. Specilizations in the vertebrae and carpus indicate close re lationship between Youngina and the tangasaurids, but eliminate tangasaurids from consider ation as ancestors of other aquatic eosuchians, archosaurs or sauropterygians. CONTENTS Page ABREVIATIONS . ..... ... ......... .......... ... ......... ..... ... ..... .. .... 101 INTRODUCTION . -

The Shoulder Girdle and Anterior Limb of Drepanosaurus Unguicaudatus

<oological Journal of the Linnean Socieg (1994), Ill: 247-264. With 12 figures The shoulder girdle and anterior limb of Drepanosaurus unguicaudatus (Reptilia, Neodiapsida) from the upper Triassic (Norian) Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/zoolinnean/article/111/3/247/2691415 by guest on 27 September 2021 of Northern Italy SILVIO RENESTO Dipartimento di Scienze della Terra, Universita degli Studi, Via Mangiagalli 34, I-20133 Milano, Italy Received January 1993, accepted for publication February 1994 A reinvestigation of the osteology of the holotype of Drepanosaurus unguicaudatus Pinna, 1980 suggests that in earlier descriptions some osteological features were misinterpreted, owing to the crushing of the bones and because taphonomic aspects were not considered. The pattern of the shoulder girdle and fore-limb was misunderstood: the supposed interclavicle is in fact the right scapula, and the bones previously identified as coracoid and scapula belong to the anterior limb. The new reconstruction of the shoulder girdle, along with the morphology of the phalanges and caudal vertebrae, leads to a new hypothesis about the mode oflife of this reptile. Drepanosaurus was probably an arboreal reptile which used its enormous claws to scrape the bark from trees, perhaps in search of insects, just as the modern pigmy anteater (Cyclopes) does. Available diagnostic characters place Drepanosaurus within the Neodiapsida Benton, but it is impossible to ascribe this genus to one or other of the two major neodiapsid lineages, the Archosauromorpha and the Lepidosauromorpha. ADDITIONAL KEY WORDS:-Functional morphology - taxonomy - taphonomy - palaeoecology . CONTENTS Introduction ................... 247 Taphonomy ..... .............. 249 Systematic palaeontology . .............. 251 Genus Drepanosaurus Pinna, 1980 .............. 252 Drepannsaurus unguicaudatus Pinna, 1980. -

71St Annual Meeting Society of Vertebrate Paleontology Paris Las Vegas Las Vegas, Nevada, USA November 2 – 5, 2011 SESSION CONCURRENT SESSION CONCURRENT

ISSN 1937-2809 online Journal of Supplement to the November 2011 Vertebrate Paleontology Vertebrate Society of Vertebrate Paleontology Society of Vertebrate 71st Annual Meeting Paleontology Society of Vertebrate Las Vegas Paris Nevada, USA Las Vegas, November 2 – 5, 2011 Program and Abstracts Society of Vertebrate Paleontology 71st Annual Meeting Program and Abstracts COMMITTEE MEETING ROOM POSTER SESSION/ CONCURRENT CONCURRENT SESSION EXHIBITS SESSION COMMITTEE MEETING ROOMS AUCTION EVENT REGISTRATION, CONCURRENT MERCHANDISE SESSION LOUNGE, EDUCATION & OUTREACH SPEAKER READY COMMITTEE MEETING POSTER SESSION ROOM ROOM SOCIETY OF VERTEBRATE PALEONTOLOGY ABSTRACTS OF PAPERS SEVENTY-FIRST ANNUAL MEETING PARIS LAS VEGAS HOTEL LAS VEGAS, NV, USA NOVEMBER 2–5, 2011 HOST COMMITTEE Stephen Rowland, Co-Chair; Aubrey Bonde, Co-Chair; Joshua Bonde; David Elliott; Lee Hall; Jerry Harris; Andrew Milner; Eric Roberts EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE Philip Currie, President; Blaire Van Valkenburgh, Past President; Catherine Forster, Vice President; Christopher Bell, Secretary; Ted Vlamis, Treasurer; Julia Clarke, Member at Large; Kristina Curry Rogers, Member at Large; Lars Werdelin, Member at Large SYMPOSIUM CONVENORS Roger B.J. Benson, Richard J. Butler, Nadia B. Fröbisch, Hans C.E. Larsson, Mark A. Loewen, Philip D. Mannion, Jim I. Mead, Eric M. Roberts, Scott D. Sampson, Eric D. Scott, Kathleen Springer PROGRAM COMMITTEE Jonathan Bloch, Co-Chair; Anjali Goswami, Co-Chair; Jason Anderson; Paul Barrett; Brian Beatty; Kerin Claeson; Kristina Curry Rogers; Ted Daeschler; David Evans; David Fox; Nadia B. Fröbisch; Christian Kammerer; Johannes Müller; Emily Rayfield; William Sanders; Bruce Shockey; Mary Silcox; Michelle Stocker; Rebecca Terry November 2011—PROGRAM AND ABSTRACTS 1 Members and Friends of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology, The Host Committee cordially welcomes you to the 71st Annual Meeting of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology in Las Vegas. -

The Largest Tropical Peat Mires in Earth History

Geological Society of America Special Paper 370 2003 Desmoinesian coal beds of the Eastern Interior and surrounding basins: The largest tropical peat mires in Earth history Stephen F. Greb William M. Andrews Cortland F. Eble Kentucky Geological Survey, University of Kentucky, Lexington, Kentucky 40506, USA William DiMichele Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of Natural History, Washington, D.C., USA C. Blaine Cecil U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia, USA James C. Hower Center for Applied Energy Research, University of Kentucky, Lexington, Kentucky, USA ABSTRACT The Colchester, Springfield, and Herrin Coals of the Eastern Interior Basin are some of the most extensive coal beds in North America, if not the world. The Colchester covers an area of more than 100,000 km^, the Springfield covers 73,500-81,000 km^, and the Herrin spans 73,900 km^. Each has correlatives in the Western Interior Basin, such that their entire regional extent varies from 116,000 km^to 200,000 km^. Correlatives in the Appalachian Basin may indicate an even more widespread area of Desmoinesian peatland development, although possibly sUghtly younger in age. The Colchester Coal is thin, but the Springfield and Herrin Coals reach thicknesses in excess of 3 m. High ash yields, dominance of vitrinite macerals, and abundant lycopsids suggest that these Desmoinesian coals were deposited in topogenous (groundwater fed) to solige- nous (mixed-water source) mires. The only modern mire complexes that are as wide- spread are northern-latitude raised-bog mires, but Desmoinesian -

Vertebrate Paleontology of the Cretaceous/Tertiary Transition of Big Bend National Park, Texas (Lancian, Puercan, Mammalia, Dinosauria, Paleomagnetism)

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1986 Vertebrate Paleontology of the Cretaceous/Tertiary Transition of Big Bend National Park, Texas (Lancian, Puercan, Mammalia, Dinosauria, Paleomagnetism). Barbara R. Standhardt Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Standhardt, Barbara R., "Vertebrate Paleontology of the Cretaceous/Tertiary Transition of Big Bend National Park, Texas (Lancian, Puercan, Mammalia, Dinosauria, Paleomagnetism)." (1986). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 4209. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/4209 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a manuscript sent to us for publication and microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to pho tograph and reproduce this manuscript, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. Pages in any manuscript may have indistinct print. In all cases the best available copy has been filmed. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. Manuscripts may not always be complete. When it is not possible to obtain missing pages, a note appears to indicate this. 2. When copyrighted materials are removed from the manuscript, a note ap pears to indicate this. 3. -

Late Paleocene) of the Eastern Crazy Mountain Basin, Montana

CONTRIBUTIONS FROM THE MUSEUM OF PALEONTOLOGY THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN VOL. 26, NO. 9, p. 157-196 December 3 1, 1983 MAMMALIAN FAUNA FROM DOUGLASS QUARRY, EARLIEST TIFFANIAN (LATE PALEOCENE) OF THE EASTERN CRAZY MOUNTAIN BASIN, MONTANA BY DAVID W. KRAUSE AND PHILIP D. GINGERICH MUSEUM OF PALEONTOLOGY THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN ANN ARBOR CONTRIBUTIONS FROM THE MUSEUM OF PALEONTOLOGY Philip D. Gingerich, Director Gerald R. Smith, Editor This series of contributions from the Museum of Paleontology is a medium for the publication of papers based chiefly upon the collection in the Museum. When the number of pages issued is sufficient to make a volume, a title page and a table of contents will be sent to libraries on the mailing list, and to individuals upon request. A list of the separate papers may also be obtained. Correspondence should be directed to the Museum of Paleontology, The University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, 48 109. VOLS. 11-XXVI. Parts of volumes may be obtained if available. Price lists available upon inquiry. MAMMALIAN FAUNA FROM DOUGLASS QUARRY, EARLIEST TIFFANIAN (LATE PALEOCENE) OF THE EASTERN CRAZY MOUNTAIN BASIN, MONTANA BY David W. ~rause'and Philip D. ~in~erich' Abstract.-Douglass Quarry is the fourth major locality to yield fossil mammals in the eastern Crazy Mountain Basin of south-central Montana. It is stratigraphically intermediate between Gidley and Silberling quarries below, which are late Torrejonian (middle Paleocene) in age, and Scarritt Quarry above, which is early Tiffanian (late Paleocene) in age. The stratigraphic position of Douglass Quarry and the presence of primitive species of Plesiadapis, Nannodectes, Phenacodus, and Ectocion (genera first appearing at the Torrejonian-Tiffanian boundary) combine to indicate an earliest Tiffanian age. -

Archaeopteris Is the Earliest Known Modern Tree

letters to nature seawater nitrate mapping systems for use in open ocean and coastal waters. Deep-Sea Res. I 43, 1763± zones as important sites for the subsequent development of lateral 1775 (1996). 26. Obata, H., Karatani, H., Matsui, M. & Nakayama, E. Fundamental studies for chemical speciation in organs; and wood anatomy strategies that minimize the mechani- seawater with an improved analytical method. Mar. Chem. 56, 97±106 (1997). cal stresses caused by perennial branch growth. Acknowledgements. We thank G. Elrod, E. Guenther, C. Hunter, J. Nowicki and S. Tanner for the iron Archaeopteris is thought to have been an excurrent tree, with a analyses and assistance with sampling, and the crews of the research vessels Western Flyer and New Horizon single trunk producing helically arranged deciduous branches for providing valuable assistance at sea. Funding was provided by the David and Lucile Packard 7 Foundation through MBARI and by the National Science Foundation. growing almost horizontally . All studies relating to the develop- ment of Archaeopteris support the view that these ephemeral Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to K.S.J. (e-mail: johnson@mlml. calstate.edu). branches arise from the pseudomonopodial division of the trunk apex8±11. Apical branching also characterizes all other contempora- neous non-seed-plant taxa including those that had also evolved an arborescent habit, such as lepidosigillarioid lycopsids and cladoxy- Archaeopteris is the earliest lalean ferns. This pattern, which can disadvantage the tree if the trunk apex is damaged, contrasts with the axillary branching knownmoderntree reported in early seed plants12. Analysis of a 4 m-long trunk from the Famennian of Oklahoma has shown that Archaeopteris may Brigitte Meyer-Berthaud*, Stephen E.