Urinalysis: a Comprehensive Review JEFF A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Treatment of Chyluria Secondary to Advanced Carcinoma of the Prostate

Prostate Cancer and Prostatic Diseases (2008) 11, 102–105 & 2008 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 1365-7852/08 $30.00 www.nature.com/pcan CASE REPORT The treatment of chyluria secondary to advanced carcinoma of the prostate SA Cluskey, A Myatt and MA Ferro Department of Urology, Huddersfield Royal Infirmary, Huddersfield, UK Chyluria has not been previously reported as being associated with carcinoma of the prostate. The most common cause is lymphatic filariasis, a parasitic disease. Non-parasitic chyluria is rare. We describe a case of chyluria associated with carcinoma of the prostate. We describe our successful management in this case and highlight how urologists may overcome problematic chyluria in patients with advanced carcinoma of the prostate. Prostate Cancer and Prostatic Diseases (2008) 11, 102–105; doi:10.1038/sj.pcan.4500994; published online 31 July 2007 Keywords: chyluria; androgen blockade; TURP Introduction 3-week history of back pain. He had not opened his bowels for 3 days but reported passage of flatus. He Chyluria occurs as a result of abnormal communication was referred to the acute surgical team for further in- between lymphatics and the urinary tract. It may be vestigation. associated with flank pain, fever, dysuria, haematuria At the time of admission, his symptoms included and chylous clot retention.1–3 Worldwide, the most general malaise, back pain and poor mobility. He was common cause is lymphatic filariasis, a mosquito-borne indeed bed bound. He reported no difficulty in passing parasitic disease endemic to tropical and subtropical urine, although he had been treated for a suspected areas. -

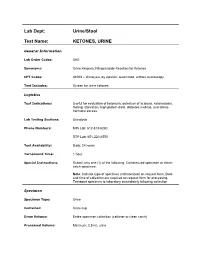

Ketones, Urine

Lab Dept: Urine/Stool Test Name: KETONES, URINE General Information Lab Order Codes: UKE Synonyms: Urine Ketones; Nitroprusside Reaction for Ketones CPT Codes: 81003 – Urinalysis, by dipstick; automated, without microscopy Test Includes: Screen for urine ketones. Logistics Test Indications: Useful for evaluation of ketonuria, detection of acidosis, ketoacidosis, fasting, starvation, high protein diets, diabetes mellitus, and stress- hormone excess. Lab Testing Sections: Urinalysis Phone Numbers: MIN Lab: 612-813-6280 STP Lab: 651-220-6550 Test Availability: Daily, 24 hours Turnaround Time: 1 hour Special Instructions: Submit only one (1) of the following: Catheterized specimen or clean- catch specimen. Note: Indicate type of specimen (catheterized) on request form. Date and time of collection are required on request form for processing. Transport specimen to laboratory immediately following collection Specimen Specimen Type: Urine Container: Urine cup Draw Volume: Entire specimen collection (catheter or clean catch) Processed Volume: Minimum: 0.5 mL urine Collection: A specimen collected by catheterization is optimal; however, a clean- catch or mid-stream specimen is also acceptable. Random, voided specimens will be accepted, but are the least desirable and are not recommended if a urine culture is also being requested. Special Processing: N/A Patient Preparation: None Sample Rejection: Less than 0.5 mL urine submitted; mislabeled or unlabeled specimen Interpretive Reference Range: Negative Critical Values: N/A Limitations: Specimens containing -

Characteristics of Presentation and Metabolic Risk Factors in Relation to Extent of Involvement in Infants with Nephrolithiasis

DOI: 10.14744/ejmi.2019.87741 EJMI 2020;4(1):78–85 Research Article Characteristics of Presentation and Metabolic Risk Factors in Relation to Extent of Involvement in Infants with Nephrolithiasis Kenan Yilmaz,1 Mustafa Erman Dorterler2 1Department of Pediatric Nephrolog, Sanliurfa Training and Research Hospital, Sanliurfa, Turkey 2Department of Pediatric Surgery, Harran University Faculty of Medicine, Sanliurfa, Turkey Abstract Objectives: To evaluate the characteristics of presentation and metabolic risk factors in relation to the extent of in- volvement in infants with nephrolithiasis. Methods: A total of 111 infants (age range 0.3–11.8 months, 58.6% were girls) diagnosed with nephrolithiasis in the first year of life were included in this retrospective study. Data on age at diagnosis, gender, family history of nephrolithiasis, parental consanguinity, symptoms on admission, urinary abnormalities, surgery, size of renal calculi, and metabolic risk factors (hypercalciuria, hyperuricosuria, hyperoxaluria, hypocitraturia, cystinuria, hypercalcemia) were recorded for each patient and compared with the number of kidneys affected (bilateral vs. unilateral), the number of kidney stones (multiple vs. single), and the kidney stone size (microlithiasis vs. larger stones). Results: Overall, 58.6% of the infants were girls. Irritability was the most common symptom on admission (34.2%). Microlithiasis (62.2%), bilateral kidney involvement (61.3%), multiple kidney stones (73.9%), and metabolic risk fac- tors (45.0%, hypercalciuria in 31.5%) were commonly noted. Bilateral nephrolithiasis was associated with significantly higher rates of hypercalciuria than unilateral nephrolithiasis (39.7% vs. 18.6%, respectively; p=0.022). The presence of multiple kidney stones was associated with a significantly higher rate of hyperuricosuria than the presence of a single kidney stone (20.7% vs. -

Chyluria in Pregnancy-A Decade of Experience in a Single Tertiary Care Hospital

Nephro Urol Mon. 2015 March; 7(2): e26309. DOI: 10.5812/numonthly.26309 Research Article Published online 2015 March 1. Chyluria in Pregnancy-A Decade of Experience in a Single Tertiary Care Hospital 1 1,* 1 1 2 Khalid Mahmood ; Ahsan Ahmad ; Kaushal Kumar ; Mahendra Singh ; Sangeeta Pankaj ; 2 Kalpana Singh 1Department of Urology, Indira Gandhi Institute of Medical Sciences, Patna, Bihar, India 2Department of Gynaecology, Indira Gandhi Institute of Medical Sciences, Patna, Bihar, India *Corresponding author : Ahsan Ahmad, Indira Gandhi Institute of Medical Sciences, Patna, Bihar, India. Tel: +91-9431457764, E-mail: [email protected] Received: ; Revised: ; Accepted: December 29, 2014 January 4, 2015 January 22, 2015 Background: Chyluria i.e. passage of chyle in urine, giving it milky appearance, is common in many parts of India but rare in west. Very few case of chyluria in pregnant female has been reported in literature. Persistence of this condition may have deleterious effects on health of child and mother. In the present study 43 cases of chyluria during pregnancy and their management seen over a period more than 10 years have been presented. Objectives: The study aims to present our experience of managing 43 cases with chyluria during pregnancy over a period of ten years from July 2003 to June 2014. Patients and Methods: Forty three pregnant patients with chyluria, who presented between July 2003 to June 2014 to the department of Urology, Indira Gandhi Institute of Medical Sciences, Patna were included. Patients underwent conservative management and/or sclerotherapy after evaluation. Follow-up of all patients was done by observation of urine color, routine examination of urine and test for post prandial chyle in urine up to 3 months after delivery. -

Acute Kidney Injury in Cancer Patients

Acute kidney injury in cancer patients Bruno Nogueira César¹ Marcelino de Souza Durão Júnior¹ ² 1. Disciplina de Nefrologia, Universidade Federal de São Paulo, São Paulo, SP, Brasil 2. Unidade de Transplante Renal Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein, São Paulo, SP, Brasil http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1806-9282.66.S1.25 SUMMARY The increasing prevalence of neoplasias is associated with new clinical challenges, one of which is acute kidney injury (AKI). In addition to possibly constituting a clinical emergency, kidney failure significantly interferes with the choice and continuation of antineoplastic therapy, with prognostic implications in cancer patients. Some types of neoplasia are more susceptible to AKI, such as multiple myeloma and renal carcinoma. In cancer patients, AKI can be divided into pre-renal, renal (intrinsic), and post-renal. Conventional platinum-based chemotherapy and new targeted therapy agents against cancer are examples of drugs that cause an intrinsic renal lesion in this group of patients. This topic is of great importance to the daily practice of nephrologists and even constitutes a subspecialty in the field, the onco-nephrology. KEYWORDS: Acute Kidney Injury. Neoplasia. Malignant tumor. Chemotherapy. INTRODUCTION With the epidemiological transition of recent de- (CT), compromises the continuation of treatment, cades, cancer has become the object of several clini- and limits the participation of patients in studies cal studies that resulted in more options for the diag- with new drugs. nosis and treatment of the disease. Thus, there was an increase in the survival of patients, and handling EPIDEMIOLOGY complications of the disease and treatment adverse effects also became more common1. -

High Urinary Calcium Excretion and Genetic Susceptibility to Hypertension and Kidney Stone Disease

High Urinary Calcium Excretion and Genetic Susceptibility to Hypertension and Kidney Stone Disease Andrew Mente,* R. John D’A. Honey,† John M. McLaughlin,* Shelley B. Bull,* and Alexander G. Logan* *Prosserman Centre for Health Research, Samuel Lunenfeld Research Institute, Mount Sinai Hospital, and Department of Public Health Sciences, and †St. Michael’s Hospital, Division of Urology, Department of Surgery, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada Increased urinary calcium excretion commonly is found in patients with hypertension and kidney stone disease (KSD). This study investigated the aggregation of hypertension and KSD in families of patients with KSD and hypercalciuria and explored whether obesity, excessive weight gain, and diabetes, commonly related conditions, also aggregate in these families. Consec- utive patients with KSD, aged 18 to 50 yr, were recruited from a population-based Kidney Stone Center, and a 24-h urine and their spouse were interviewed by telephone (333 ؍ sample was collected. The first-degree relatives of eligible patients (n to collect demographic and health information. Familial aggregation was assessed using generalized estimating equations. Multivariate-adjusted odds ratios (OR) revealed significant associations between hypercalciuria in patients and hypertension (OR 2.9; 95% confidence interval 1.4 to 6.2) and KSD (OR 1.9; 95% confidence interval 1.03 to 3.5) in first-degree relatives, specifically in siblings. No significant associations were found in parents or spouses or in patients with hyperuricosuria. Similarly, no aggregation with other conditions was observed. In an independent study of siblings of hypercalciuric patients with KSD, the adjusted mean fasting urinary calcium/creatinine ratio was significantly higher in the hypertensive siblings compared with normotensive siblings (0.60 ؎ 0.32 versus 0.46 ؎ 0.28 mmol/mmol; P < 0.05), and both sibling groups had significantly higher values than the unselected study participants (P < 0.001). -

Different Response of Body Weight Change According to Ketonuria After Fasting in the Healthy Obese

ORIGINAL ARTICLE Endocrinology, Nutrition & Metabolism http://dx.doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2012.27.3.250 • J Korean Med Sci 2012; 27: 250-254 Different Response of Body Weight Change According to Ketonuria after Fasting in the Healthy Obese Hyeon-Jeong Kim1, Nam-Seok Joo1, The relationship between obesity and ketonuria is not well-established. We conducted a Kwang-Min Kim1, Duck-Joo Lee1, retrospective observational study to evaluate whether their body weight reduction response and Sang-Man Kim2 differed by the presence of ketonuria after fasting in the healthy obese. We used the data of 42 subjects, who had medical records of initial urinalysis at routine health check-up and 1Department of Family Practice and Community Health, Ajou University School of Medicine, Suwon; follow-up urinalysis in the out-patient clinic, one week later. All subjects in the initial 2Department of Family Medicine, CHA Biomedical urinalysis showed no ketonuria. However, according to the follow-up urinalysis after three Center, CHA University College of Medicine, Seoul, subsequent meals fasts, the patients were divided into a non-ketonuria group and Korea ketonuria group. We compared the data of conventional low-calorie diet programs for ± Received: 20 August 2011 3 months for both groups. Significantly greater reduction of body weight (-8.6 3.6 kg vs 2 2 Accepted: 17 January 2012 -1.1 ± 2.2 kg, P < 0.001), body mass index (-3.16 ± 1.25 kg/m vs -0.43 ± 0.86 kg/m , P < 0.001) and waist circumference (-6.92 ± 1.22 vs -2.32 ± 1.01, P < 0.001) was Address for Correspondence: observed in the ketonuria group compared to the non-ketonuria group. -

Deficient Diabetic Mice

Diminished Loss of Proteoglycans and Lack of Albuminuria in Protein Kinase C-␣–Deficient Diabetic Mice Jan Menne,1,2 Joon-Keun Park,2 Martin Boehne,2 Marlies Elger,2 Carsten Lindschau,2 Torsten Kirsch,2 Matthias Meier,2 Faikah Gueler,2 Annette Fiebeler,3 Ferdinand H. Bahlmann,2 Michael Leitges,4 and Hermann Haller2 Activation of protein kinase C (PKC) isoforms has been implicated in the pathogenesis of diabetic nephropathy. We showed earlier that PKC-␣ is activated in the kid- iabetes affects Ͼ300 million people worldwide; -neys of hyperglycemic animals. We now used PKC-␣؊/؊ 20–40% will develop overt nephropathy. Diabe mice to test the hypothesis that this PKC isoform tes is the most common cause of end-stage mediates streptozotocin-induced diabetic nephropathy. Drenal disease. The earliest clinical sign of ne- We observed that renal and glomerular hypertrophy was phropathy is microalbuminuria. Microalbuminuria also ؊ ؊ similar in diabetic wild-type and PKC-␣ / mice. How- heralds impending cardiovascular morbidity and mortality ever, the development of albuminuria was almost absent (1–4). Microalbuminuria predicts overt proteinuria, which ؊/؊␣ in the diabetic PKC- mice. The hyperglycemia-in- is now believed to actively promote renal insufficiency (5). duced downregulation of the negatively charged base- Therefore, successful treatment of diabetic patients ment membrane heparan sulfate proteoglycan perlecan -؊ ؊ should aim for the prevention or regression of albumin was completely prevented in the PKC-␣ / mice, com- pared with controls. We then asked whether transform- uria. Hyperglycemia seems to cause microalbuminuria in   diabetic patients (6,7). However, how the metabolic dis- ing growth factor- 1 (TGF- 1) and/or vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is implicated in the turbance causes cellular effects is incompletely under- PKC-␣–mediated changes in the basement membrane. -

Ideal Conditions for Urine Sample Handling, and Potential in Vitro Artifacts Associated with Urine Storage

Urinalysis Made Easy: The Complete Urinalysis with Images from a Fully Automated Analyzer A. Rick Alleman, DVM, PhD, DABVP, DACVP Lighthouse Veterinary Consultants, LLC Gainesville, FL Ideal conditions for urine sample handling, and potential in vitro artifacts associated with urine storage 1) Potential artifacts associated with refrigeration: a) In vitro crystal formation (especially, calcium oxalate dihydrate) that increases with the duration of storage i) When clinically significant crystalluria is suspected, it is best to confirm the finding with a freshly collected urine sample that has not been refrigerated and which is analyzed within 60 minutes of collection b) A cold urine sample may inhibit enzymatic reactions in the dipstick (e.g. glucose), leading to falsely decreased results. c) The specific gravity of cold urine may be falsely increased, because cold urine is denser than room temperature urine. 2) Potential artifacts associated with prolonged storage at room temperature, and their effects: a) Bacterial overgrowth can cause: i) Increased urine turbidity ii) Altered pH (1) Increased pH, if urease-producing bacteria are present (2) Decreased pH, if bacteria use glucose to form acidic metabolites iii) Decreased concentration of chemicals that may be metabolized by bacteria (e.g. glucose, ketones) iv) Increased number of bacteria in urine sediment v) Altered urine culture results b) Increased urine pH, which may occur due to loss of carbon dioxide or bacterial overgrowth, can cause: i) False positive dipstick protein reaction ii) Degeneration of cells and casts iii) Alter the type and amount of crystals present 3) Other potential artifacts: a) Evaporative loss of volatile substances (e.g. -

Article Twenty-Four Hour Urine Testing and Prescriptions For

CJASN ePress. Published on November 11, 2019 as doi: 10.2215/CJN.03580319 Article Twenty-Four Hour Urine Testing and Prescriptions for Urinary Stone Disease–Related Medications in Veterans Shen Song,1 I-Chun Thomas,2 Calyani Ganesan,1 Ericka M. Sohlberg ,3 Glenn M. Chertow,1 Joseph C. Liao,2,3 Simon Conti,2,3 Christopher S. Elliott,3,4 Alan C. Pao,1,2,3 and John T. Leppert1,2,3 Abstract Background and objectives Current guidelines recommend 24-hour urine testing in the evaluation and treatment 1Division of of persons with high-risk urinary stone disease. However, how much clinicians use information from 24-hour Nephrology, urine testing to guide secondary prevention strategies is unknown. We sought to determine the degree to which Departments of clinicians initiate or continue stone disease–related medications in response to 24-hour urine testing. Medicine and 3Urology, Stanford Design, setting, participants, & measurements We examined a national cohort of 130,489 patients with incident University School of Medicine, Stanford, urinary stone disease in the Veterans Health Administration between 2007 and 2013 to determine whether California; 2Veterans prescription patterns for thiazide diuretics, alkali therapy, and allopurinol changed in response to 24-hour urine Affairs Palo Alto testing. Health Care System, Palo Alto, California; 4 fi and Division of Results Stone formers who completed 24-hour urine testing (n=17,303; 13%) were signi cantly more likely to be Urology, Santa Clara prescribed thiazide diuretics, alkali therapy, and allopurinol compared with those who did not complete a 24-hour Valley Medical Center, urine test (n=113,186; 87%). -

KETON.Zemia and KETONURIA in CHILDHOOD. by MURIEL J

Arch Dis Child: first published as 10.1136/adc.1.5.302 on 1 January 1926. Downloaded from KETON.zEMIA AND KETONURIA IN CHILDHOOD. BY MURIEL J. BROWN, M.B., Ch.B., D.P.H., AND GRACE GRAHAMI, AM.D. From the Medical Department, The Royal Hospital for Sick Children, Glasgow. The formation of ketone bodies and their excretion in the urine in albnormall amounts have for many years been problems of much interest to both physiologist and clinician. Much of our present knowledge of the subject has been gained from the study of carbohydrate metabolism in diabetes, where ketonuria in its classical formi is frequently observed. From this it has been established that an excess of ketone bodies occurs in the blood when the fats are incompletely ' combusted ' as a result of abnormal carbohydrate metabolism, and ample justification has been provided for the well-known sta.tement myiade by Rosenfeld(l) in 1895 ' that fat burns only in the fire of carbohydrate.' A good review of our present knowledge of ketone production and its prevention is to be found in Shaffer's recent lecture entitled ' Antiketo- genesis, its Mechanism and Signifiecance. '(2) A fu-ll discussion of the stubject in all its aspects is not within the scope of the present communication, but we may quote that ' there no Shaffer's statement is to-day question that http://adc.bmj.com/ ketosis is due to carbohydrate starvation,' and make special reference also to his remninder that the inhibitory effect of carbohydrate on ketone formation depends, not on the mnere existence of sufficient glucose, as glucose, in the blood (cf. -

Hypouricaemia and Hyperuricosuria in Familial Renal Glucosuria

Clin Kidney J (2013) 6: 523–525 doi: 10.1093/ckj/sft100 Advance Access publication 5 September 2013 Clinical Report Hypouricaemia and hyperuricosuria in familial renal glucosuria Inês Aires1,2, Ana Rita Santos1, Jorge Pratas3, Fernando Nolasco1 and Joaquim Calado1,2 1Department of Medicine and Nephrology, Faculdade de Ciências Médicas, Universidade NOVAde Lisboa-Hospital de Curry Cabral, Lisboa, Portugal, 2Department of Genetics, Faculdade de Ciências Médicas, Universidade NOVAde Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal and 3Department of Nephrology, Hospitais Universitários de Coimbra, Coimbra, Portugal Correspondence and offprint requests to: Joaquim Calado; E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Familial renal glucosuria is a rare co-dominantly inherited benign phenotype characterized by the presence of glucose in the urine. It is caused by mutations in the SLC5A2 gene that encodes SGLT2, the Na+-glucose cotransporter responsible for the reabsorption of the bulk of glucose in the proxi- mal tubule. We report a case of FRG displaying both severe glucosuria and renal hypouricaemia. We hypothesize that glucosuria can disrupt urate reabsorption in the proximal tubule, directly causing hyperuricosuria. Keywords: glucose; kidney; SGLT2; urate Background urate values were found to be raised, with an excretion of 7.33 mmol (1242 mg)/1.73 m2/24 h or 0.13 mmol (21.5 mg)/kg of body weight and a fractional excretion of 20%. Familial renal glucosuria (FRG) is characterized by the Phosphorus (urinary and serum), bicarbonate (plasma) presence of glucose in the urine in the absence of dia- and immunoglobulin light chains (urine) were all within betes mellitus or generalized proximal tubular dysfunc- normal range (data not shown).