Second International Symposium on the Future of Corrections

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Female Drug Users in European Prisons –

University of Hamburg With financial support from the AGIS Programme European Commission Directorate General Justice and Home Affairs Female drug users in European prisons – best practice for relapse prevention and reintegration FINAL REPORT AND RECOMMENDATIONS NOVEMBER 2004 Project number: JAI/2003/AGIS/191 Responsible Scientist Heike Zurhold ● Heino Stöver ● Christian Haasen Centre for Interdisciplinary Addiction Research University of Hamburg Martinistraße 52 D-20246 Hamburg Germany Email: [email protected] Acknowledgements This study made considerable demands on different groups of participants who provided us with requested data described in this report. The responsible partners of the European research project are grateful to all European Ministries of Justice joining the prison service survey. We are also grateful to numerous staff of prison authorities and drug services who provided us with access to female drug users in prison and with necessary information. Last not least special thanks to the female drug users who agreed to be interviewed about their about their history of drug use and imprisonments and their experiences with drug services. Heike Zurhold, Hamburg Jacek Moskalewicz & Justyna Zulewska-Sak, Warsaw Xavier Majo Roca & Cristina Sanclemente, Barcelona Gabriele Schmied, Vienna David Shewan & Gabriele Vojt, Glasgow Heino Stöver, Bremen TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY...................................................................... 8 1 INTRODUCTION.........................................................................18 -

Women's Health in Prison in the Northern Dimension Area

Northern Dimension Partnership in Public Health and Social Well-being NDPHS Expert Group on Prison Health Thematic Report Women’s Health in Prison in the Northern Dimension Area NDPHS Series No. 3/2008 Northern Dimension Partnership in Public Health and Social Well-being (NDPHS) NDPHS thematic report: Women’s Health in Prison in the Northern Dimension Area The views reflected in this paper are those of the members of the NDPHS Expert Group on Prison Health who have developed it and should not, therefore, be interpreted otherwise. If specific country data are not available in this report, this is because the authors were either unable to obtain it or did not receive permission to publish this data. Editors: Ingrid Lycke Ellingsen, Elo Kocys and Maxi Nachtigall Pictures: Juerg Christandl, Amy Allock Maps: NDPHS, Nordic Council of Ministers This paper may be freely reproduced and reprinted, provided that the source is cited. It is also available on-line in the Papers’ section of the NDPHS Database at http://www.ndphs.org/?database,view,paper,19 View our website at www.ndphs.org and keep an eye on policy developments and explore the world of the NDPHS – a partnership committed to achieving tangible results! Further information: NDPHS Secretariat Strömsborg P.O. Box 2010 103 11 Stockholm, SWEDEN Phone (switchboard): +46 8 440 1920 Fax: +46 8 440 1944 E-mail: [email protected] The paper arises from the project “NDPHS Project Database” which has received funding from the European Union, in the framework of the Public Health Programme. The sole responsibility for that document lies with the NDPHS Expert Group on Prison Health. -

Harm Reduction in European Prisons a Compilation of Models of Best Practice

Series Health Promotion in Prisons Schriftenreihe Gesundheitsförderung im Justizvollzug European Network on Drugs and Infections Prevention in Prison (ENDIPP) Cranstoun Drug Services Heino Stöver, Morag MacDonald, Susie Atherton Harm Reduction in European Prisons A Compilation of Models of Best Practice BIS-Verlag der Carl von Ossietzky Universität Oldenburg Copyright © 2007 Printed in Germany. This project was partly funded by the European Commission. Neither the European Commission nor any person acting on its behalf are liable for the use of information contained in this report. Distibution Cranstoun Drug Services. If you would like to request further copies of this report, please contact [email protected]. Copies are priced at €25 / £17. Publishers The European Network on Drugs and Infections Prevention in Prison ENDIPP Cranstoun Drug Services 1st Floor St Andrews House 26–27 Victoria Road Surbiton, London, KT6 4JX United Kingdom BIS-Verlag der Carl von Ossietzky Universität Oldenburg Postfach 25 41 26015 Oldenburg Tel.: 0441/798 2261, Telefax: 0441/798 4040 E-mail: [email protected] Internet: www.ibit.uni-oldenburg.de Also appears as Volume 16 of the series “Gesundheitsförderung im Justizvollzug” (Health Promotion in Prisons) ISBN 978-3-8142-2090-1 Contents Acknowledgements 9 List of Tables and Figures 11 Executive Summary 13 Chapter 1 – Introduction 25 Chapter 2 – Methodology 27 2.1 Methodological approach 27 2.2 Aims and objectives 27 2.3 Details of institutions visited and participants interviewed 28 2.4 Definition -

Final Report on Prevention, Treatment, and Harm Reduction Services

Drug policy and harm reduction SANCO/2006/C4/02 Final Report on Prevention, Treatment, and Harm Reduction Services in Prison, on Reintegration Services on Release from Prison and Methods to Monitor/Analyse Drug use among Prisoners April 2008 WIAD Wissenschaftliches Institut der Centre for Interdisciplinary Ärzte Deutschlands gem. e.V. Addiction Research (CIAR) Neither the European Commission nor any person acting on its behalf is responsible for the use which might be made of the information contained herein. H. Stöver1, C. Weilandt3, H. Zurhold2, C. Hartwig1, K. Thane1,2 1 Bremen Institute for Drug Research (BISDRO), University of Bremen 2 Centre for Interdisciplinary Addiction Research (CIAR), University of Hamburg 3 Scientific Institute of the German Medical Association (WIAD gem. e.V.), Bonn Corresponding address: WIAD Ubierstrasse 78 D-53173 Bonn Germany tel 49 228 8104 182 fax +49 228 8104 1736 home www.wiad.de Executive Summary 1. Status-quo of prevention, treatment and harm reduction services for people in prisons, reintegration services for persons on release from prisons The main objective of this work package was to analyse the status-quo of prevention, treatment and harm reduction services for people in prisons and in reintegration services for persons on release from prisons. The report is based on data on health interventions targeting imprisoned drug users as well as on relevant information included in the national action plans on social inclusion prepared by the Member States within the context of the open method of coordination on social protection and social inclusion. A key result of this work package is that there is a need for more systematic research on the effectiveness of treatment for drug users in prison, as there is hardly any high-quality research in this field, especially in the EU. -

Towards a Continuum of Care in the EU Criminal Justice System a Survey of Prisoners’ Needs in Four Countries (Estonia, Hungary, Lithuania, Poland)

Schriftenreihe „Gesundheitsförderung im Justizvollzug“ – „Health Promotion in Prisons“ Herausgegeben von H. Stöver, J. Jacob „Gesundheitsförderung zielt auf einen Prozess, allen Menschen ein höhe- res Maß an Selbstbestimmung über ihre Gesundheit zu ermöglichen und sie damit zur Stärkung ihrer Gesundheit zu befähigen. Um ein angemesse- nes körperliches und seelisches Wohlbefinden zu erlangen, ihre Wünsche und Hoffnungen wahrnehmen und verwirklichen, sowie ihre Umwelt meis- tern bzw. sie verändern zu können“. Diese Gedanken leiten die Ottawa- Charta zur Gesundheitsförderung ein, die 1986 von einer internationalen Konferenz verabschiedet wurde. Versucht man den Leitgedanken der Ottawa-Charta, die Stärkung der Selbstbestimmung über die Gesundheit, auf den Strafvollzug zu beziehen, stößt man schnell an Grenzen der Über- tragbarkeit: Äußere Beschränkungen, Fremdbestimmungen, eingeschränkte Rechte prägen das Leben und die gesundheitliche Lage der Gefangenen. Mit der Schriftenreihe „Gesundheitsförderung im Justizvollzug“ wollen wir Beiträge veröffentlichen, die innovative gesundheitspolitische Anregun- gen für den Justizvollzug geben und gesundheitsfördernde Praxisformen des Vollzugsalltags vorstellen. Außerhalb des Vollzugs bewährte Präventionsangebote und Versorgungs- strukturen werden auf ihre Relevanz zur Verbesserung der gesundheitli- chen Situation Inhaftierter hin überprüft und auf die Bedingungen des Jus- tizvollzugs bezogen. Letztendlich kann nur eine größere Transparenz und Durchlässigkeit des Systems „Justizvollzug“ dazu beitragen, -

CONSCIOUS an Inter-Systemic Model for Preventing Reoffending By

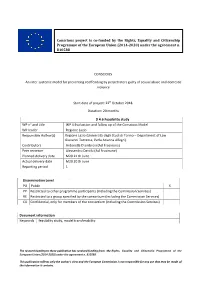

Conscious project is co-funded by the Rights, Equality and Citizenship Programme of the European Union (2014-2020) under the agreement n. 810588 CONSCIOUS An inter-systemic model for preventing reoffending by perpetrators guilty of sexual abuse and domestic violence Start date of project: 22st October 2018. Duration: 20 months D 4.6 Feasibility study WP n° and title WP 4 Evaluation and follow up of the Conscious Model WP leader Regione Lazio Responsible Author(s) Regione Lazio (Università degli Studi di Torino – Department of Law Giovanni Torrente, Perla Arianna Allegri). Contributors Antonella D’ambrosi (Asl Frosinone) Peer reviewer Alessandro Dattilo (Asl Frosinone) Planned delivery date M20 21 th June Actual delivery date M20 20 th June Reporting period 1 Dissemination Level PU Public X PP Restricted to other programme participants (including the Commission Services) RE Restricted to a group specified by the consortium (including the Commission Services) CO Confidential, only for members of the consortium (including the Commission Services) Document information Keywords feasibility study, model transferability The research leading to these publication has received funding from the Rights, Equality and Citizenship Programme of the European Union (2014-2020) under the agreement n. 810588 This publication reflects only the author’s view and the European Commission is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information it contains. Document history Version Date Reviewed paragraphs Short description 0.1 05.06.2020 First release Drafting First release 0.2 10.06.2020 All Peer review request implementation to meet GA description. 0.3 17.06.2020 All Peer review request implementation to meet GA description. -

Zur Homepage Der Publikation

Schriftenreihe „Gesundheitsförderung im Justizvollzug“ Herausgegeben von H. Stöver, J. Jacob „Gesundheitsförderung zielt auf einen Prozess, allen Menschen ein höheres Maß an Selbstbestimmung über ihre Gesundheit zu ermögli- chen und sie damit zur Stärkung ihrer Gesundheit zu befähigen. Um ein angemessenes körperliches und seelisches Wohlbefinden zu erlan- gen, ihre Wünsche und Hoffnungen wahrnehmen und verwirklichen, sowie ihre Umwelt meistern bzw. sie verändern zu können“. Diese Gedanken leiten die Ottawa-Charta zur Gesundheitsförderung ein, die 1986 von einer internationalen Konferenz verabschiedet wurde. Ver- sucht man den Leitgedanken der Ottawa-Charta, die Stärkung der Selbstbestimmung über die Gesundheit, auf den Strafvollzug zu be- ziehen, stößt man schnell an Grenzen der Übertragbarkeit: Äußere Beschränkungen, Fremdbestimmungen, eingeschränkte Rechte prägen das Leben und die gesundheitliche Lage der Gefangenen. Mit der Schriftenreihe „Gesundheitsförderung im Justizvollzug“ wol- len wir Beiträge veröffentlichen, die innovative gesundheitspolitische Anregungen für den Justizvollzug geben und gesundheitsfördernde Praxisformen des Vollzugsalltags vorstellen. Außerhalb des Vollzugs bewährte Präventionsangebote und Versor- gungsstrukturen werden auf ihre Relevanz zur Verbesserung der ge- sundheitlichen Situation Inhaftierter hin überprüft und auf die Bedin- gungen des Justizvollzugs bezogen. Letztendlich kann nur eine größere Transparenz und Durchlässigkeit des Systems „Justizvollzug“ dazu beitragen, individuelle gesundheits- orientierte -

A Study of the Health Care Provision, Existing Drug Services and Strategies Operating in Prisons in Ten Countries from Central and Eastern Europe

European Institute for Crime Prevention and Control, affiliated with the United Nations (HEUNI) P.O.Box 444 FIN-00531 Helsinki Finland Publication Series No. 45 A Study of the Health Care Provision, Existing Drug Services and Strategies Operating in Prisons in Ten Countries from Central and Eastern Europe Morag MacDonald (University of Central England) Helsinki 2005 Copies can be purchased from: Academic Bookstore Criminal Justice Press P.O.Box 128 P.O.Box 249 FIN-00101 Helsinki Monsey, NY 10952 Finland USA Website: http://www.akateeminen.fi Website: http://www.criminaljusticepress.com ISBN 952-5333-23-X ISSN 1237-4741 Page layout: DTPage Oy, Helsinki, Finland Printed by Hakapaino Oy, Helsinki, Finland Acknowledgements The completion of this study would have been impossible without the support and assistance of a wide range of individuals. I would like to thank the members of the Scientific Advisory Group:MrRoy Walmsley, the International Centre for Prison Studies in London (England), Dr Heino Stöver, the University of Bremen (Germany), Professor Joris Casselman, the Catholic University of Leuven (Belgium), Ms Laetitia Hennebel, Cranstoun Drug Services (UK). Mrs. Terhi Viljanen, the European Institute for Crime Prevention and Control affiliated with the United Nations (HEUNI) for her encouragement and support throughout the research. I would like to thank the Directors General of the Prison Service in the ten central and eastern European countries for having authorised the research & for having provided logistic support: Mr Peter Vassilev (Bulgaria); Mrs Kamila Meclová (Czech Republic); Mr Peter Näks (Estonia); Mr. István Bökönyi (Hun- gary); Mr Dailis Luks (Latvia); Mr Rymvidas Kugis (Lithuania); Mr Jan Pyrcak (Poland); Mr Emilian Stănișor (Romania); Mr Oto Lobodáš (Slovakia) and Mr Dušan Valentinčič (Slovenia).