A Performance and Pedagogical Analysis of Paul Bowles Song

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JAMES CUMMINS BOOKSELLER Catalogue 109 to Place Your Order, Call, Write, E-Mail Or Fax

JAMES CUMMINS BOOKSELLER catalogue 109 To place your order, call, write, e-mail or fax: JAMES CUMMINS BOOKSELLER 699 Madison Avenue, New York City, 10065 Telephone (212) 688-6441 Fax (212) 688-6192 e-mail: [email protected] www.jamescumminsbookseller.com hours: Monday - Friday 10:00 - 6:00, Saturday 10:00 - 5:00 Members A.B.A.A., I.L.A.B. front cover: Ross, Ambrotype school portraits, item 139 inside front cover: Mason, The Punishments of China, item 102 inside rear cover: Micro-calligraphic manuscript, item 29 rear cover: Steichen, Portrait of Gene Tunney, item 167 terms of payment: All items, as usual, are guaranteed as described and are returnable within 10 days for any reason. All books are shipped UPS (please provide a street address) unless otherwise requested. Overseas orders should specify a shipping preference. All postage is extra. New clients are requested to send remittance with orders. Libraries may apply for deferred billing. All New York and New Jersey residents must add the appropriate sales tax. We accept American Express, Master Card, and Visa. 1. (ANDERSON, Alexander) Bewick, Thomas. A General History of Quadrupeds. The Figures engraved on wood chiefly copied from the original of T. Bewick, by A. Anderson. With an Appendix, containing some American Animals not hitherto described. x, 531 pp. 8vo, New York: Printed by G. & E. Waite, No. 64, Maiden-Lane, 1804. First American edition. Modern half brown morocco and cloth by Sangorski & Sutcliffe. Occasional light spotting, old signature of William S. Barnes on title. Hugo p. 24; S&S 5843; Roscoe, App. -

Thomson, Virgil (1896-1989) by Patricia Juliana Smith

Thomson, Virgil (1896-1989) by Patricia Juliana Smith Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Entry Copyright © 2002, glbtq, Inc. Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com Virgil Thomson in 1947. Photograph by Carl van Critic and composer Virgil Thomson was a pioneer in creating a specifically American Vechten, June 4, 1947. Library of Congress form of classical music that is at once "serious" yet whimsically sardonic. He is best Prints and Photographs known as Gertrude Stein's collaborator in two operas, Four Saints in Three Acts (1934) Division. and The Mother of Us All (1947). The hymn melodies that shape the score of Four Saints are an echo of Thomson's earliest musical career, that of an organist in a Baptist church in Kansas City, Missouri, where he was born on November 25, 1896 into a tolerant, middle-class family. His mother especially encouraged his musical and artistic talents, which were obvious very early. Thomson joined the United States Army in 1917 and served during World War I. After the war, he studied music at Harvard University, where he discovered Tender Buttons (1914), Stein's playful and elaborately encoded poetic work of lesbian eroticism. He subsequently studied composition in Paris under Nadia Boulanger, the mentor of at least two generations of modern composers. In 1925 he finally met Stein, whose works he had begun to set to music. In Paris, he also met Jean Cocteau, Igor Stravinsky, and Erik Satie, the latter of whom influenced his music greatly. There he also cemented a relationship with painter Maurice Grosser, who was to become his life partner and frequent collaborator (for example, Grosser directed Four Saints in Three Acts and devised the scenario for The Mother of Us All). -

The Trumpet As a Voice of Americana in the Americanist Music of Gershwin, Copland, and Bernstein

THE TRUMPET AS A VOICE OF AMERICANA IN THE AMERICANIST MUSIC OF GERSHWIN, COPLAND, AND BERNSTEIN DOCUMENT Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Amanda Kriska Bekeny, M.M. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2005 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Timothy Leasure, Adviser Professor Charles Waddell _________________________ Dr. Margarita Ophee-Mazo Adviser School of Music ABSTRACT The turn of the century in American music was marked by a surge of composers writing music depicting an “American” character, via illustration of American scenes and reflections on Americans’ activities. In an effort to set American music apart from the mature and established European styles, American composers of the twentieth century wrote distinctive music reflecting the unique culture of their country. In particular, the trumpet is a prominent voice in this music. The purpose of this study is to identify the significance of the trumpet in the music of three renowned twentieth-century American composers. This document examines the “compositional” and “conceptual” Americanisms present in the music of George Gershwin, Aaron Copland, and Leonard Bernstein, focusing on the use of the trumpet as a voice depicting the compositional Americanisms of each composer. The versatility of its timbre allows the trumpet to stand out in a variety of contexts: it is heroic during lyrical, expressive passages; brilliant during festive, celebratory sections; and rhythmic during percussive statements. In addition, it is a lead jazz voice in much of this music. As a dominant voice in a variety of instances, the trumpet expresses the American character of each composer’s music. -

Cbcopland on The

THE UNITED STATES ARMY FIELD BAND The Legacy of AARON COPLAND Washington, D.C. “The Musical Ambassadors of the Army” rom Boston to Bombay, Tokyo to Toronto, the United States Army Field Band has been thrilling audiences of all ages for more than fifty years. As the pre- mier touring musical representative for the United States Army, this in- Fternationally-acclaimed organization travels thousands of miles each year presenting a variety of music to enthusiastic audiences throughout the nation and abroad. Through these concerts, the Field Band keeps the will of the American people behind the members of the armed forces and supports diplomatic efforts around the world. The Concert Band is the oldest and largest of the Field Band’s four performing components. This elite 65-member instrumental ensemble, founded in 1946, has performed in all 50 states and 25 foreign countries for audiences totaling more than 100 million. Tours have taken the band throughout the United States, Canada, Mexico, South America, Europe, the Far East, and India. The group appears in a wide variety of settings, from world-famous concert halls, such as the Berlin Philharmonie and Carnegie Hall, to state fairgrounds and high school gymnasiums. The Concert Band regularly travels and performs with the Sol- diers’ Chorus, together presenting a powerful and diverse program of marches, over- tures, popular music, patriotic selections, and instrumental and vocal solos. The orga- nization has also performed joint concerts with many of the nation’s leading orchestras, including the Boston Pops, Cincinnati Pops, and Detroit Symphony Orchestra. The United States Army Field Band is considered by music critics to be one of the most versatile and inspiring musical organizations in the world. -

New World Records

New World Records NEW WORLD RECORDS 701 Seventh Avenue, New York, New York 10036; (212) 302-0460; (212) 944-1922 fax email: [email protected] www.newworldrecords.org Songs of Samuel Barber and Ned Rorem New World NW 229 Songs of Samuel Barber romanticism brought him early success as a com- poser. Because of his First Symphony (1936, amuel Barber was born on March 9, 1910, in revised 1942), Bruno Walter thought of him as SWest Chester, Pennsylvania. He remembers “the pioneer of the American symphony.”(“That’s that his parents never particularly encouraged not true,” said Barber almost forty years later. him to become a musician, but as his mother’s “That should be Roy Harris.”) In the late thirties sister, the renowned Metropolitan Opera singer Barber was the first American to be performed Louise Homer, was a frequent visitor to the by Arturo Toscanini (Adagio for Strings and First Barber home, the atmosphere there was not at all Essay for Orchestra), and, not long after, his inimical to musical aspirations. Barber began to music was championed by artists of the stature study piano at six and composed his first music a of Bruno Walter (First Symphony and Second year later (a short piano piece in C minor called Essay for Orchestra), Eugene Ormandy (Violin “Sadness”). When he was ten he composed one Concerto), Artur Rodzinski (First Symphony), act of an opera, The Rose Tree, to a libretto by Serge Koussevitsky (Second Symphony), Martha the family’s Irish cook. At fourteen Barber Graham (Medea), and Vladimir Horowitz entered the newly opened Curtis Institute of (Excursions and Piano Sonata). -

Cultural Appropriation in Classical Music: Annotated Bibliography

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Musicology and Ethnomusicology: Student Scholarship Musicology and Ethnomusicology 11-2018 Cultural Appropriation in Classical Music: Annotated Bibliography University of Denver Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/musicology_student Part of the Musicology Commons Recommended Citation University of Denver, "Cultural Appropriation in Classical Music: Annotated Bibliography" (2018). Musicology and Ethnomusicology: Student Scholarship. 20. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/musicology_student/20 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. This Bibliography is brought to you for free and open access by the Musicology and Ethnomusicology at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Musicology and Ethnomusicology: Student Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. Cultural Appropriation in Classical Music: Annotated Bibliography This bibliography is available at Digital Commons @ DU: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/musicology_student/20 Cultural Appropriation in Classical Music: Annotated Bibliography Andrews, Jean. "Teresa Berganza's Re-appropriation of Carmen." Journal of Romance Studies 14, no. 1 (2014): 19-39. Andrews speaks on how to fix a history of appropriation. Much of classical repertoire comes from past, made in a time when the population had different sensibilities. t is unfair to hold the past to modern sensibilities. Though modern performances of these works can be slightly changed to combat this history of appropriation. Andrews analysis Teresa Berganza contribution in changing the role to adhere to a better cultural context. Birnbaum, Michael. "Jewish Music, German Musicians: Cultural Appropriation and the Representation of a Minority in the German Klezmer Scene." Leo Baeck Institute Year Book 54, no. -

Thesis Title

Inhabiting the Exotic: Paul Bowles and Morocco by Bouchra Benlemlih B.A. (Sidi Mohammed Ben Abdellah University) M.A. (Toulouse-Le Mirail University) Ph.D. (Toulouse-Le Mirail University) Thesis submitted to The University of Nottingham in candidacy for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2009 1 Abstract The American writer Paul Bowles lived in Morocco from 1947 until his death in 1999, apart from visits to North Africa, Europe, Ceylon, India and the United States during this period. Bowles‘ expatriation and subsequent itineraries are quite well known, but this thesis explores his interest in – indeed, preoccupation with – mediations and a state of being ‗in-between‘ in a selection of his texts: the translations, his autobiography and his fiction. Only a few commentators on Bowles‘ work have noted a meta-fictional dimension in his texts, possibly because the facts of his life are so intriguing and even startling. Though not explicitly meta-fictional, in the manner of somewhat later writers, Bowles does not tell us directly how he understands the various in- betweens that may be identified in his work, and their relationship to the individual and social crises about which he writes. His work unravels the effects of crises as not directly redeemable but as mediated and over-determined in complex and subtle forms. There are no explicit postmodern textual strategies; rather, Bowles draws on the basic resources of fiction to locate, temporally and spatially, the in-between: plot, character, description and background are intertwined in order, at once, to give a work its unity and to reveal, sometimes quite incidentally, a supplementary quality that threatens to undermine that unity. -

John La Montaine Collection

JOHN LA MONTAINE COLLECTION RUTH T. WATANABE SPECIAL COLLECTIONS SIBLEY MUSIC LIBRARY EASTMAN SCHOOL OF MUSIC UNIVERSITY OF ROCHESTER Prepared by Gail E. Lowther Summer 2016 John La Montaine (at far right) presents John F. Kennedy with score to From Sea to Shining Sea, op. 30, which had been commissioned for Kennedy’s inauguration ceremony, with Jackie Kennedy and Howard Mitchell (National Symphony Orchestra conductor) (1961). Photograph from John La Montaine Collection, Box 16, Folder 9, Sleeve 1. John La Montaine and Howard Hanson during rehearsal with the Eastman Philharmonia in preparation for the performance of La Montaine’s Concerto for Piano and Orchestra, op. 9, at Carnegie Hall (November 1962). Photograph from ESPA 27-32 (8 x 10). 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Description of Collection . 5 Description of Series . 6 INVENTORY Series 1: Manuscripts and sketches Sub-series A: Student works and sketches . 12 Sub-series B: Mature works . 13 Sub-series C: Works with no opus number . 43 Sub-series D: Sketches . 54 Series 2: Personal papers Sub-series A: Original writings . 58 Sub-series B: Notes on composition projects . 59 Sub-series C: Pedagogical material . 65 Sub-series D: Ephemera . 65 Series 3: Correspondence Sub-series A: Correspondence to/from John La Montaine . 69 Sub-series B: Correspondence to/from Paul Sifler . 88 Sub-series C: Other correspondents . 89 Series 4: Publicity and press materials Sub-series A: Biographical information . 91 Sub-series B: Resume and works lists . 91 Sub-series C: Programs, articles, and reviews . 92 Sub-series D: Additional publicity materials . 104 3 Series 5: Library Sub-series A: Published literature . -

The American Stravinsky

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE THE AMERICAN STRAVINSKY THE AMERICAN STRAVINSKY The Style and Aesthetics of Copland’s New American Music, the Early Works, 1921–1938 Gayle Murchison THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN PRESS :: ANN ARBOR TO THE MEMORY OF MY MOTHERS :: Beulah McQueen Murchison and Earnestine Arnette Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2012 All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America ϱ Printed on acid-free paper 2015 2014 2013 2012 4321 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978-0-472-09984-9 Publication of this book was supported by a grant from the H. Earle Johnson Fund of the Society for American Music. “Excellence in all endeavors” “Smile in the face of adversity . and never give up!” Acknowledgments Hoc opus, hic labor est. I stand on the shoulders of those who have come before. Over the past forty years family, friends, professors, teachers, colleagues, eminent scholars, students, and just plain folk have taught me much of what you read in these pages. And the Creator has given me the wherewithal to ex- ecute what is now before you. First, I could not have completed research without the assistance of the staff at various libraries. -

Copyright and Use of This Thesis This Thesis Must Be Used in Accordance with the Provisions of the Copyright Act 1968

COPYRIGHT AND USE OF THIS THESIS This thesis must be used in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Reproduction of material protected by copyright may be an infringement of copyright and copyright owners may be entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. Section 51 (2) of the Copyright Act permits an authorized officer of a university library or archives to provide a copy (by communication or otherwise) of an unpublished thesis kept in the library or archives, to a person who satisfies the authorized officer that he or she requires the reproduction for the purposes of research or study. The Copyright Act grants the creator of a work a number of moral rights, specifically the right of attribution, the right against false attribution and the right of integrity. You may infringe the author’s moral rights if you: - fail to acknowledge the author of this thesis if you quote sections from the work - attribute this thesis to another author - subject this thesis to derogatory treatment which may prejudice the author’s reputation For further information contact the University’s Director of Copyright Services sydney.edu.au/copyright Paul Bowles’ Aesthetics of Containment Surrealism, Music, the Short Story Sam V. H. Reese A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Arts The University of Sydney 2014 Acknowledgments 3 Introduction 5 Chapter 1: Bowles, Freedom and America Bowles and the Critics 13 Freedom and Liberal Criticism 26 Patterns -

Philharmonia Orchestra Esa-Pekka Salonen, Principal Conductor & Artistic Advisor

Friday, March 15, 2019, 8pm Zellerbach Hall Philharmonia Orchestra Esa-Pekka Salonen, principal conductor & artistic advisor Esa-Pekka Salonen, conductor Truls Mørk, cello Jean SIBELIuS (1865 –1957) e Oceanides (Aallottaret ), Op. 73 Esa-Pekka SALONEN ( b. 1958) Cello Concerto Truls Mørk, cello Ella Wahlström, sound design INTERMISSION Béla BARTóK (1881 –1945) Concerto for Orchestra, BB 123 Introduzione: Andante non troppo – Allegro vivace Giuoco delle coppie: Allegretto scherzando Elegia: Andante non troppo Intermezzo interrotto: Allegretto Finale: Pesante – Presto Tour supported by the Philharmonia Foundation and the generous donors to the Philharmonia’s Future 75 Campaign. philharmonia.co.uk Major support for Philharmonia Orchestra’s residency provided by The Bernard Osher Foundation, Patron Sponsors Gail and Dan Rubinfeld, and generous donors to the Matías Tarnopolsky Fund for Cal Performances. Cal Performances’ 2018 –19 season is sponsored by Wells Fargo. 17a PROGRAM NOTES Jean Sibelius I should never have believed it,” he said.) He was e Oceanides (Aallottaret ), Op. 73 taken to a fashionable New York hotel, where In June 1913, the Helsinki papers reported that his host surprised him with the announcement Jean Sibelius, the brightest ornament of Finnish that Yale university wished to present him culture, had declined an invitation to journey with an honorary doctorate on June 6th in New to America to conduct some of his music, Haven. On the next day, he was taken to the though he did agreed to accept membership Stoeckel’s rural Connecticut mansion, which in the National Music Society and provide the Sibelius described as a “wonderful estate among publishing house of Silver Burdett with ree wooded hills, intersected by rivers and shim - Songs for American School Children . -

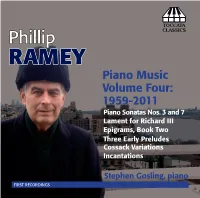

Toccata Classics TOCC0153 Notes

TOCCATA 1 21 CLASSICS 2 22 3 23 Phillip 4 24 RAMEY 5 25 6 26 7 27 8 28 Piano Music 9 29 10 30 Volume Four: 11 31 12 32 1959-2011 13 14 33 Piano Sonatas Nos. 3 and 7 15 16 Lament for Richard III 17 34 Epigrams, Book Two 35 Three Early Preludes 18 36 Cossack Variations 19 20 Incantations Stephen Gosling, piano FIRST RECORDINGS PHILLIP RAMEY PIANO MUSIC, VOLUME FOUR: 1959–2011 by Benjamin Folkman Although the American composer Phillip Ramey has produced an appreciable body of orchestral and chamber music – including a horn concerto premiered by Philip Myers with the New York Philharmonic conducted by Leonard Slatkin – the piano has been his favoured medium throughout his career. Eight sonatas, the substantial Piano Fantasy and numerous multi-movement sets are highlights of a solo-piano catalogue of some ity scores – about half of his musical output. he piano also igures prominently in Ramey’s symphonic eforts, featured in three concertos, the Concert Suite for Piano and Orchestra and the Color Etudes for Piano and Orchestra. he three previous albums in Toccata Classics’ survey of Ramey’s piano music, played by Stephen Gosling (tocc 0029, tocc 0114) and Mirian Conti (tocc 0077), included his Sonatas Nos. 1, 2, 4, 5 and 6, the Piano Fantasy and several sets (among them, Diversions, Epigrams, Book One and the solo-piano version of the Color Etudes), along with numerous shorter works, some composed as late as 2010. he present Volume Four spans more than half-a-century of creativity, ranging from the hree Early Preludes of 1959 to the Piano Sonata No.