Hyperbolic Cosines and Sines Theorems for the Triangle Formed by Intersection of Three Semicircles on Euclidean Plane

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Plane Trigonometry - Lecture 16 Section 3.2: the Law of Cosines

Plane Trigonometry - Lecture 16 Section 3.2: The Law of Cosines Summary: http://www.math.ksu.edu/~gerald/math150/sum16.pdf Course page: http://www.math.ksu.edu/~gerald/math150/ Gerald Hoehn April 1, 2019 Law of cosines Theorem Let ∆ABC any triangle, then c2 = a2 + b2 − 2ab cos γ b2 = a2 + c2 − 2ac cos β a2 = b2 + c2 − 2bc cos α We may reformulate the statement also in word form. Theorem In any triangle, the square of the length of a side equals the sum of the squares of the length of the other two sides minus twice the product of the length of the other two sides and the cosine of the angle between them. Solving Triangles For solving triangles ∆ABC one needs at least three of the six quantities a, b, and c and α, β, γ. One distinguishes six essential different cases forming three classes: I AAA case: Three angles given. I AAS case: Two angles and a side opposite one of them given. I ASA case: Two angles and the side between them given. I SSA case: Two sides and an angle opposite one of them given. I SAS case: Two sides and the angle between them given. I SSS case: Three sides given. The case AAA cannot be solved. The cases AAS, ASA and SSA are solved by using the law of sines. The cases SAS, SSS are solved by using the law of cosines. Solving Triangles: the SAS case For the SAS case a unique solution always exists. Three steps: 1. Use the law of cosines to determine the length of the third side opposite to the given angle. -

Einstein's Velocity Addition Law and Its Hyperbolic Geometry

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Computers and Mathematics with Applications 53 (2007) 1228–1250 www.elsevier.com/locate/camwa Einstein’s velocity addition law and its hyperbolic geometry Abraham A. Ungar∗ Department of Mathematics, North Dakota State University, Fargo, ND 58105, USA Received 6 March 2006; accepted 19 May 2006 Abstract Following a brief review of the history of the link between Einstein’s velocity addition law of special relativity and the hyperbolic geometry of Bolyai and Lobachevski, we employ the binary operation of Einstein’s velocity addition to introduce into hyperbolic geometry the concepts of vectors, angles and trigonometry. In full analogy with Euclidean geometry, we show in this article that the introduction of these concepts into hyperbolic geometry leads to hyperbolic vector spaces. The latter, in turn, form the setting for hyperbolic geometry just as vector spaces form the setting for Euclidean geometry. c 2007 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Keywords: Special relativity; Einstein’s velocity addition law; Thomas precession; Hyperbolic geometry; Hyperbolic trigonometry 1. Introduction The hyperbolic law of cosines is nearly a century old result that has sprung from the soil of Einstein’s velocity addition law that Einstein introduced in his 1905 paper [1,2] that founded the special theory of relativity. It was established by Sommerfeld (1868–1951) in 1909 [3] in terms of hyperbolic trigonometric functions as a consequence of Einstein’s velocity addition of relativistically admissible velocities. Soon after, Varicakˇ (1865–1942) established in 1912 [4] the interpretation of Sommerfeld’s consequence in the hyperbolic geometry of Bolyai and Lobachevski. -

Old-Fashioned Relativity & Relativistic Space-Time Coordinates

Relativistic Coordinates-Classic Approach 4.A.1 Appendix 4.A Relativistic Space-time Coordinates The nature of space-time coordinate transformation will be described here using a fictional spaceship traveling at half the speed of light past two lighthouses. In Fig. 4.A.1 the ship is just passing the Main Lighthouse as it blinks in response to a signal from the North lighthouse located at one light second (about 186,000 miles or EXACTLY 299,792,458 meters) above Main. (Such exactitude is the result of 1970-80 work by Ken Evenson's lab at NIST (National Institute of Standards and Technology in Boulder) and adopted by International Standards Committee in 1984.) Now the speed of light c is a constant by civil law as well as physical law! This came about because time and frequency measurement became so much more precise than distance measurement that it was decided to define the meter in terms of c. Fig. 4.A.1 Ship passing Main Lighthouse as it blinks at t=0. This arrangement is a simplified model for a 1Hz laser resonator. The two lighthouses use each other to maintain a strict one-second time period between blinks. And, strict it must be to do relativistic timing. (Even stricter than NIST is the universal agency BIGANN or Bureau of Intergalactic Aids to Navigation at Night.) The simulations shown here are done using RelativIt. Relativistic Coordinates-Classic Approach 4.A.2 Fig. 4.A.2 Main and North Lighthouses blink each other at precisely t=1. At p recisel y t=1 sec. -

6.2 Law of Cosines

6.2 Law of Cosines The Law of Sines can’t be used directly to solve triangles if we know two sides and the angle between them or if we know all three sides. In this two cases, the Law of Cosines applies. Law of Cosines: In any triangle ABC , we have a2 b 2 c 2 2 bc cos A b2 a 2 c 2 2 ac cos B c2 a 2 b 2 2 ab cos C Proof: To prove the Law of Cosines, place triangle so that A is at the origin, as shown in the Figure below. The coordinates of the vertices BC and are (c ,0) and (b cos A , b sin A ) , respectively. Using the Distance Formula, we have a2( c b cos) A 2 (0 b sin) A 2 =c2 2bc cos A b 2 cos 2 A b 2 sin 2 A =c2 2bc cos A b 2 (cos 2 A sin 2 A ) =c22 2bc cos A b =b22 c 2 bc cos A Example: A tunnel is to be built through a mountain. To estimate the length of the tunnel, a surveyor makes the measurements shown in the Figure below. Use the surveyor’s data to approximate the length of the tunnel. Solution: c2 a 2 b 2 2 ab cos C 21222 388 2 212 388cos82.4 173730.23 c 173730.23 416.8 Thus, the tunnel will be approximately 417 ft long. Example: The sides of a triangle are a5, b 8, and c 12. Find the angles of the triangle. -

5.4 Law of Cosines and Solving Triangles (Slides 4-To-1).Pdf

Solving Triangles and the Law of Cosines In this section we work out the law of cosines from our earlier identities and then practice applying this new identity. c2 = a2 + b2 − 2ab cos C: (1) Elementary Functions Draw the triangle 4ABC on the Cartesian plane with the vertex C at the Part 5, Trigonometry origin. Lecture 5.4a, The Law of Cosines Dr. Ken W. Smith Sam Houston State University 2013 In the drawing sin C = y and cos C = x : We may relabel the x and y Smith (SHSU) Elementary Functions 2013 1 / 22 Smith (SHSU) b Elementary Functionsb 2013 2 / 22 coordinates of A(x; y) as x = b cos C and y = b sin C: Solving Triangles and the Law of Cosines One Angle and the Law of Cosines We get information if we compute c2: By the Pythagorean theorem, c2 = (y2) + (a − x)2 = (b sin C)2 + (a − b cos C)2 = b2 sin2 C + a2 − 2ab cos C + b2 cos2 C: c2 = a2 + b2 − 2ab cos C: We use the Pythagorean identity to simplify b2 sin2 C + b2 cos2 C = b2 and so It is straightforward to use the law of cosines when we know one angle and c2 = a2 + b2 − 2ab cos C its two adjacent sides. This is the Side-Angle-Side (SAS) case, in which we may label the angle C and its two sides a and b and so we can solve for the side c. Or, if we have the Side-Side-Side (SSS) situation, in which we know all three sides, we can label one angle C and solve for that angle in terms of the sides a; b and c, using the law of cosines. -

Hyperbolic Trigonometry in Two-Dimensional Space-Time Geometry

Hyperbolic trigonometry in two-dimensional space-time geometry F. Catoni, R. Cannata, V. Catoni, P. Zampetti ENEA; Centro Ricerche Casaccia; Via Anguillarese, 301; 00060 S.Maria di Galeria; Roma; Italy January 22, 2003 Summary.- By analogy with complex numbers, a system of hyperbolic numbers can be intro- duced in the same way: z = x + hy; h2 = 1 x, y R . As complex numbers are linked to the { ∈ } Euclidean geometry, so this system of numbers is linked to the pseudo-Euclidean plane geometry (space-time geometry). In this paper we will show how this system of numbers allows, by means of a Cartesian representa- tion, an operative definition of hyperbolic functions using the invariance respect to special relativity Lorentz group. From this definition, by using elementary mathematics and an Euclidean approach, it is straightforward to formalise the pseudo-Euclidean trigonometry in the Cartesian plane with the same coherence as the Euclidean trigonometry. PACS 03 30 - Special Relativity PACS 02.20. Hj - Classical groups and Geometries 1 Introduction Complex numbers are strictly related to the Euclidean geometry: indeed their invariant (the module) arXiv:math-ph/0508011v1 3 Aug 2005 is the same as the Pythagoric distance (Euclidean invariant) and their unimodular multiplicative group is the Euclidean rotation group. It is well known that these properties allow to use complex numbers for representing plane vectors. In the same way hyperbolic numbers, an extension of complex numbers [1, 2] defined as z = x + hy; h2 =1 x, y R , { ∈ } are strictly related to space-time geometry [2, 3, 4]. Indeed their square module given by1 z 2 = 2 2 | | zz˜ x y is the Lorentz invariant of two dimensional special relativity, and their unimodular multiplicative≡ − group is the special relativity Lorentz group [2]. -

Hyperbolic Geometry

Flavors of Geometry MSRI Publications Volume 31,1997 Hyperbolic Geometry JAMES W. CANNON, WILLIAM J. FLOYD, RICHARD KENYON, AND WALTER R. PARRY Contents 1. Introduction 59 2. The Origins of Hyperbolic Geometry 60 3. Why Call it Hyperbolic Geometry? 63 4. Understanding the One-Dimensional Case 65 5. Generalizing to Higher Dimensions 67 6. Rudiments of Riemannian Geometry 68 7. Five Models of Hyperbolic Space 69 8. Stereographic Projection 72 9. Geodesics 77 10. Isometries and Distances in the Hyperboloid Model 80 11. The Space at Infinity 84 12. The Geometric Classification of Isometries 84 13. Curious Facts about Hyperbolic Space 86 14. The Sixth Model 95 15. Why Study Hyperbolic Geometry? 98 16. When Does a Manifold Have a Hyperbolic Structure? 103 17. How to Get Analytic Coordinates at Infinity? 106 References 108 Index 110 1. Introduction Hyperbolic geometry was created in the first half of the nineteenth century in the midst of attempts to understand Euclid’s axiomatic basis for geometry. It is one type of non-Euclidean geometry, that is, a geometry that discards one of Euclid’s axioms. Einstein and Minkowski found in non-Euclidean geometry a This work was supported in part by The Geometry Center, University of Minnesota, an STC funded by NSF, DOE, and Minnesota Technology, Inc., by the Mathematical Sciences Research Institute, and by NSF research grants. 59 60 J. W. CANNON, W. J. FLOYD, R. KENYON, AND W. R. PARRY geometric basis for the understanding of physical time and space. In the early part of the twentieth century every serious student of mathematics and physics studied non-Euclidean geometry. -

Using Differentials to Differentiate Trigonometric and Exponential Functions Tevian Dray

Using Differentials to Differentiate Trigonometric and Exponential Functions Tevian Dray Tevian Dray ([email protected]) received his B.S. in mathematics from MIT in 1976, his Ph.D. in mathematics from Berkeley in 1981, spent several years as a physics postdoc, and is now a professor of mathematics at Oregon State University. A Fellow of the American Physical Society for his early work in general relativity, his current research interests include the octonions as well as science education. He directs the Vector Calculus Bridge Project. (http://www.math.oregonstate.edu/bridge) Differentiating a polynomial is easy. To differentiate u2 with respect to u, start by computing d.u2/ D .u C du/2 − u2 D 2u du C du2; and then dropping the last term, an operation that can be justified in terms of limits. Differential notation, in general, can be regarded as a shorthand for a formal limit argument. Still more informally, one can argue that du is small compared to u, so that the last term can be ignored at the level of approximation needed. After dropping du2 and dividing by du, one obtains the derivative, namely d.u2/=du D 2u. Even if one regards this process as merely a heuristic procedure, it is a good one, as it always gives the correct answer for a polynomial. (Physicists are particularly good at knowing what approximations are appropriate in a given physical context. A physicist might describe du as being much smaller than the scale imposed by the physical situation, but not so small that quantum mechanics matters.) However, this procedure does not suffice for trigonometric functions. -

Al-Kāshi's Law of Cosines

THEOREM OF THE DAY al-Kashi’s¯ Law of Cosines If A is the angle at one vertex of a triangle, a is the opposite side length, and b and c are the adjacent side lengths, then a2 = b2 + c2 2bc cos A. − = Euclid Book 2, Propositions 12 and 13 + definition of cosine If a triangle has vertices A, B and C and side lengths AB, AC and BC, and if the perpendicular through B to the line through A andC meets this line at D, and if the angle at A is obtuse then BC2 = AB2 + AC2 + 2AC.AD, while if the angle at A is acute then the lastterm on the right-hand-side is subtracted. Euclid’s two propositions supply the Law of Cosines by observing that AD = AB cos(∠DAB) = AB cos 180◦ ∠CAB = AB cos(∠CAB); while in the acute angle − − case (shown above left as the triangle on vertices A, B′, C), the subtracted length AD′ is directly obtained as AB′ cos(∠D′AB′) = AB′ cos(∠CAB′). The Law of Cosines leads naturally to a quadratic equation, as illustrated above right. Angle ∠BAC is given as 120◦; the triangle ABC has base b = 1 and opposite 2 2 2 2 side length a = √2. What is the side length c = AB? We calculate √2 = 1 + c 2 1 c cos 120◦, which gives c + c 1 = 0, with solutions ϕ and 1/ϕ, where − × × − − ϕ = 1 + √5 /2 is the golden ratio. The positive solution is the length of side AB; the negative solution corresponds to the 2nd point where a circle of radius √2 meets the line through A and B. -

Cheryl Jaeger Balm Hyperbolic Function Project

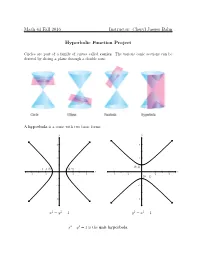

Math 43 Fall 2016 Instructor: Cheryl Jaeger Balm Hyperbolic Function Project Circles are part of a family of curves called conics. The various conic sections can be derived by slicing a plane through a double cone. A hyperbola is a conic with two basic forms: y y 4 4 2 2 • (0; 1) (−1; 0) (1; 0) • • x x -4 -2 2 4 -4 -2 2 4 (0; −1) • -2 -2 -4 -4 x2 − y2 = 1 y2 − x2 = 1 x2 − y2 = 1 is the unit hyperbola. Hyperbolic Functions: Similar to how the trigonometric functions, cosine and sine, correspond to the x and y values of the unit circle (x2 + y2 = 1), there are hyperbolic functions, hyperbolic cosine (cosh) and hyperbolic sine (sinh), which correspond to the x and y values of the right side of the unit hyperbola (x2 − y2 = 1). y y -1 1 x x π π 3π 2π π π 3π 2π 2 2 2 2 -1 -1 cos x sin x y y 6 2 4 x 2 -2 2 • (0; 1) -2 x -2 2 cosh x sinh x Hyperbolic Angle: Just like how the argument for the trigonometric functions is an angle, the argument for the hyperbolic functions is something called a hyperbolic angle. Instead of being defined by arc length, the hyperbolic angle is defined by area. If that seems confusing, consider the area of the circular sector of the unit circle. The r2θ equation for the area of a circular sector is Area = 2 , so because the radius of the unit circle is 1, any sector of the unit circle will have an area equal to half of the sector's central θ angle, A = 2 . -

The History of the Law of Cosine (Law of Al Kahsi) Though The

The History of The Law of Cosine (Law of Al Kahsi) Though the cosine did not yet exist in his time, Euclid 's Elements , dating back to the 3rd century BC, contains an early geometric theorem equivalent to the law of cosines. The case of obtuse triangle and acute triangle (corresponding to the two cases of negative or positive cosine) are treated separately, in Propositions 12 and 13 of Book 2. Trigonometric functions and algebra (in particular negative numbers) being absent in Euclid's time, the statement has a more geometric flavor. Proposition 12 In obtuse-angled triangles the square on the side subtending the obtuse angle is greater than the squares on the sides containing the obtuse angle by twice the rectangle contained by one of the sides about the obtuse angle, namely that on which the perpendicular falls, and the straight line cut off outside by the perpendicular towards the obtuse angle. --- Euclid's Elements, translation by Thomas L. Heath .[1] This formula may be transformed into the law of cosines by noting that CH = a cos( π – γ) = −a cos( γ). Proposition 13 contains an entirely analogous statement for acute triangles. It was not until the development of modern trigonometry in the Middle Ages by Muslim mathematicians , especially the discovery of the cosine, that the general law of cosines was formulated. The Persian astronomer and mathematician al-Battani generalized Euclid's result to spherical geometry at the beginning of the 10th century, which permitted him to calculate the angular distances between stars. In the 15th century, al- Kashi in Samarqand computed trigonometric tables to great accuracy and provided the first explicit statement of the law of cosines in a form suitable for triangulation . -

THE LAW of COSINES a Mathematical Vignette Ed Barbeau, University of Toronto a Key Difficulty with Any Syllabus Is Having It

THE LAW OF COSINES A mathematical vignette Ed Barbeau, University of Toronto A key difficulty with any syllabus is having it come across to students as a collection of isolated facts and techniques. It is desirable to have topics that are central to the syllabus but are capable of making connections across it. A wonderful exmaple of this is based on the law of cosines and its use in connecting trigonometry, the theory of the quadratic and the ambiguous case in Euclidean geometry. Recall that the Cosine Law states that, if a; b; c are the sides of a triangle and A is the angle opposite side a, then a2 = b2 + c2 − 2bc cos A: This formula is often used to determine the third side when two sides and the contained angle is given, or to determine an angle of the triangle when the three sides are given. However, it is of more than passing interest when the third side to be determine is not opposite the given angle. Thus, suppose that we are given sides a and b, along with an angle A opposite to one of the given sides and are asked to find the third side. Then, according to the Cosine Law, we are being asked to solve the quadratic equation x2 − (2b cos A)x + (b2 − a2) = 0: The discriminant of this quadratic equation is 4(a2 − b2 sin2 A): The quadratic will have real solutions if and only if a ≥ b sin A. What does this correspond to geoemtrically? In a triangle ABC, b sin A is the length of the perpendicular dropped from C to the side AB, and for a viable triangle, this cannot be greater than the side opposite the angle A.