An Empirical Study on the Restaurant Industry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INFORM ATION to USERS the Quality of This Reproduction Is

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type o f computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back o f the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor MI 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 SPATIAL CONSUMPTION DECISION-MAKING: SIX STUDIES OF RESTAURANT CHOICE DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Perry L. -

Anderson Restaurant Options During Pandemic- Delivery/Carryout City Of

ANDERSON RESTAURANT OPTIONS DURING PANDEMIC- DELIVERY/CARRYOUT 29th Street Café Bob Evans 765-649-1238 765-643-0064 2904 Columbus Ave. 5555 S. Scatterfield Rd. Anderson Country Club- Bobbers Café Open to Public 765-393-2128 765-642-0100 1117 Alexandria Pike 602 Northshore Blvd Buffalo Wild Wings Anderson Fish, Chicken & 765-640-2999 Gyro 5901 S Scatterfield Rd. 765-400-5580 730 West 53rd Street Burro Loco 765-640-6565 Art's Pizza Broadway 21 W 8th Street 765-643-2787 2027 Broadway St. BYOB 765-393-0458 Art's Pizza Scatterfield 1023 Meridian St. 765-642-2787 4762 S. Scatterfield Rd. Caminos De Michoacan 765-274-5591 Art's Varsity Pizza 323 East 14th Street 765-643-4447 2822 Main Street CITY OF ANDERSON #ANDERSONTOGETHER ANDERSON RESTAURANT OPTIONS DURING PANDEMIC- DELIVERY/CARRYOUT Cracker Barrel (Anderson) Greek's Pizzeria (Anderson) 765-642-6424 765-640-5300 2012 E 59th St. 6317 Dr. MLK Jr. Blvd. Creatures of Habit Heaven's Delight 765-400-0116 765-609-8001 1031 Meridian St. 1309 Park Rd. Dominoes Pizza Jack's Donuts of Anderson 765-644-2900 765-393-2036 1827 E 18th Street 1909 University Blvd. 765-400-5597 DTs R Bar 2643 Enterprise Drive 765-644-7750 1100 Dr. MLK Jr. Blvd. Kettle Top Brewhouse 765-274-5320 Frisch's 1213 Meridian Street 765-644-1223 500 Broadway Street Kroakerheads 765-649-7311 Gene's Rootbeer Stand 1239 Meridian Street 765-642-5768 640 S. Scatterfield Rd. Lee's Chicken 765-649-0888 20 E 29th Street CITY OF ANDERSON #ANDERSONTOGETHER ANDERSON RESTAURANT OPTIONS DURING PANDEMIC- DELIVERY/CARRYOUT Little Caesars Ninja of Japan 765-641-7500 765-393-2613 921 East 38th Street 21 West 38th Street Mancino's Pizza and On Broadway Grinders 765-642-7270 765-642-2300 44 Jackson Street 1606 S. -

Combined Guide for Web.Pdf

2015-16 American Preseason Player of the Year Nic Moore, SMU 2015-16 Preseason Coaches Poll Preseason All-Conference First Team (First-place votes in parenthesis) Octavius Ellis, Sr., F, Cincinnati Daniel Hamilton, So., G/F, UConn 1. SMU (8) 98 *Markus Kennedy, R-Sr., F, SMU 2. UConn (2) 87 *Nic Moore, R-Sr., G, SMU 3. Cincinnati (1) 84 James Woodard, Sr., G, Tulsa 4. Tulsa 76 5. Memphis 59 Preseason All-Conference Second Team 6. Temple 54 7. Houston 48 Troy Caupain, Jr., G, Cincinnati Amida Brimah, Jr., C, UConn 8. East Carolina 31 Sterling Gibbs, GS, G, UConn 9. UCF 30 Shaq Goodwin, Sr., F, Memphis 10. USF 20 Shaquille Harrison, Sr., G, Tulsa 11. Tulane 11 [*] denotes unanimous selection Preseason Player of the Year: Nic Moore, SMU Preseason Rookie of the Year: Jalen Adams, UConn THE AMERICAN ATHLETIC CONFERENCE Table Of Contents American Athletic Conference ...............................................2-3 Commissioner Mike Aresco ....................................................4-5 Conference Staff .......................................................................6-9 15 Park Row West • Providence, Rhode Island 02903 Conference Headquarters ........................................................10 Switchboard - 401.244-3278 • Communications - 401.453.0660 www.TheAmerican.org American Digital Network ........................................................11 Officiating ....................................................................................12 American Athletic Conference Staff American Athletic Conference Notebook -

Pocket Guide to Low Sodium Foods

CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .............................................................................7 Use Less Salt ...............................................................................8 Tips to Reduce Salt ....................................................................8 Become Sodium Conscious ............................................................9 Foods High in Sodium ................................................................9 Note to the Hypertensive ............................................................. 10 FOOD LABELING GUIDELINES ...................................................... 12. What the Label Tells You .............................................................. 12. Nutritional Content Claims ........................................................... 13. Calories and Nutrients ................................................................ 13. DINING OUT ................................................................................ 17 USING THIS GUIDE ...................................................................... 18 Nutritive Criteria ........................................................................ 19 Author’s Note ............................................................................. 2.0 Abbreviations and Symbols ......................................................... 2.1 Food Measurements and Equivalents ............................................. 2.1 Reading the Nutritive Values ........................................................ 2.2. PART 1 – GROCERY -

Business Directory

r Cleveland Avenue Redevelopment Area 2 2021 Business Directory Accommodations …….……………………………………………………3 Arts & Entertainment ...……………………………………………………3 Banks.………………………………………………………………………4 Daycare…..…………………………………………………………………4 Dining………………………………………………………………………5 Faith………………………………………………………………………...9 Grocery & Markets ………………………………………………………10 Information .....……………………………………………………………11 Legal ..……………………………………………………………………..12 Medical ...…………………………………………………………………12 Services ..…………………………………………………………………15 Shopping ...……………………………………………………………….30 WWW.CITYFTMYERS.COM/CRA Cleveland Avenue Redevelopment Area 3 2021 Business Directory Budget Inn Of Ft. Myers Howard Johnson Inn 3715 Cleveland Ave. 4811 S Cleveland Ave. 239-936-2181 239-936-3229 Website Website Deluxe Inn La Quinta Inn #819 3358 Cleveland Ave. 4850 S Cleveland Ave. 239-936-1259 214-492-6823 Website Golf View Motel, Inc. 3523 Cleveland Ave. Travel Inn 239-936-1858 2939 Cleveland Ave. Website 239-332-1330 Website Holiday Inn 2431 Cleveland Ave. Travelodge Fort Myers 239-332-3232 4760 S. Cleveland Ave. Website 786-210-8563 Website Allure’s Gentlemen’s Club Jungle Range 3654 Cleveland Ave. 4125 Cleveland Ave. 1260 714-267-6700 239-939-5464 Website Website Gracie Jiu-Jitsu Gym Just One Of Those Dayz LLC 4218 Cleveland Ave. 39 Mildred #7 239-800-4784 239-850-4137 Website Website Howl Lemon Hookah Lounge 4160 Cleveland Ave. 4460 Cleveland Ave. Units C & D 239-332-0161 239-689-5075 Website Website WWW.CITYFTMYERS.COM/CRA Cleveland Avenue Redevelopment Area 4 2021 Business Directory Mad Soul Center Splatter Dayz LLC 5245 Ramsey Way D4 39 Mildred #1 786-531-6390 239-224-8971 Website Website Peyko Venue USA Bida 4224 Cleveland Ave. -#1&2 5100 S. Cleveland Ave. #312 239-691-0961 239-841-6901 Website WAYJ FM Radio Rascals 1860 Boyscout Dr #202 3758 Cleveland Ave. -

Skyline Chili Menu

FRIES POTATOES Chili Cheese Fries 3-Way Potato 840 Cal 620 Cal Cheese Fries Cheddar Potato 740 Cal 630 Cal Fries Sour Cream Potato 430 Cal 460 Cal ® BOWLS IT’S SKYLINE TIME. Specially priced for children age ten and under. Includes small beverage and special dessert. Loaded Chili Bowl Our secret-recipe chili with beans and onions topped Kids’ 3-Way with shredded cheddar cheese and sour cream. A small 3-Way 480 Cal 440-620 Cal Coney Bowl Kids’ P’sghetti Three of our specially made hot dogs in a bowl A small dish of our spaghetti topped of our original secret-recipe chili, topped with with shredded cheddar cheese. shredded cheddar cheese. 360-540 Cal 710 Cal Kids’ Coney Our famous Chili Coney with or without cheese. desserts 270-570 Cal FUNNEL FRIES Kids’ Hot Doggy 340 Cal Two of our delicious hot dogs in one freshly steamed bun, with or without cheese. Ask about our 310-610 Cal current dessert options. THE SKYLINE STORY From a small kitchen in Kastoria, Greece, Nicholas Lambrinides watched his mother prepare authentic Greek dishes. Her recipes were unique, wonderful dishes that brought her family together. Nicholas dreamed of one day bringing these family recipes to America, where he would share them with friends and family. In 1949, his dream came true when he opened a restaurant overlooking the skyline of Cincinnati, Ohio. Since then, Skyline’s Coneys, Ways and table-side service have been enjoyed by generations. Our entrees continue to be made from Nicholas’s original recipes, using his secret blend of spices and the highest quality ingredients. -

Make Your Mark on the Skyline Strong Amenity Base

MAKE YOUR MARK ON THE SKYLINE STRONG AMENITY BASE. DIFFERENTIATING LEVEL OF SERVICE. FRESH VISION. HIGHLIGHTS INCLUDE • Expanded and modernized main lobby • Updated elevators, common corridors, and restrooms • Second floor complimentary conference room and pre-function lounge • Garage restoration, including: new LED lighting and strengthened wayfinding signage • Reimagined back plaza • Integrated signage throughout RENOVATED 489-SPACE PARKING 2ND FLOOR COMMUNAL HUB GARAGE BENEATH THE BUILDING CONFERENCE CENTER AND SKYWALK PRE-FUNCTION LOUNGE COMMUNITY MANAGER ENERGY STAR LABEL STAFFED/ON-SITE COVID-19 SCREENING ON-SITE SECURITY 24/7/365 TECHNOLOGY 360˚ LOOK FOR OUR 360 TOUR BUTTONS! 2 | COLUMBIA PLAZA 3 | COLUMBIA PLAZA GENERAL BUILDING INFORMATION TYPICAL FLOORPLATE Approx 20,000 SF TYPICAL CEILING HEIGHT 8’-6” to 9’ finished, 13’ deck to deck ELEVATOR SERVICE Three banks of (4) elevators (1-12. 13-21, 22-29) SECURITY 24/7/365 Guard Service, Closed Circuit TV System ACCESS CONTROL DSX Card Access System, expandable for tenant “piggy back” sub-systems Providers with fiber in building; Cincinnati Bell, Time Warner, Cogent Communications. TELECOM DAS (distributed antennae system – cell signal booster)- open system Installed throughout building, current provid-ers on system: Verizon FLOOR LOAD 80 PSF “live load” Central plant, electric driven centrifugal water chillers de-liver chilled water to (1) primary AHU on each floor HVAC Fan powered VAV boxes deliver supply air to specified zones Heating: Exterior Zone fan power boxes with electric -

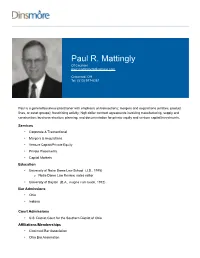

Paul R. Mattingly of Counsel [email protected]

Paul R. Mattingly Of Counsel [email protected] Cincinnati, OH Tel: (513) 977-8281 Paul is a general business practitioner with emphasis on transactions; mergers and acquisitions (entities, product lines, or asset groups); franchising activity; high dollar contract agreements involving manufacturing, supply and construction; business structure planning; and documentation for private equity and venture capital investments. Services • Corporate & Transactional • Mergers & Acquisitions • Venture Capital/Private Equity • Private Placements • Capital Markets Education • University of Notre Dame Law School (J.D., 1975) o Notre Dame Law Review, notes editor • University of Dayton (B.A., magna cum laude, 1972) Bar Admissions • Ohio • Indiana Court Admissions • U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Ohio Affiliations/Memberships • Cincinnati Bar Association • Ohio Bar Association • Colerain Township o Juvenile referee o Board of Zoning Appeals past chairman • Notre Dame Law Association, Board of Directors past president • Notre Dame Club of Greater Cincinnati Distinctions • Peer Review Rated AV in Martindale-Hubbell • Best Lawyers© o Corporate, Franchise, Leveraged Buyouts, and Private Equity Law (2021) Experience Representation of Richwood Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Representation from inception of Richwood Pharmaceuticals, Inc., through sale to British based plc. Flagship product is Adderall, an attention deficit disorder drug. Representative Transactions: 1. Acquisition of Rexar Pharmacal, N.Y based manufacturer of products, including Obetrol, which after additional research and configuration became the Adderall® line of products approved by the FDA. 2. Acquisition of Manufacturing Chemists, Inc, Indianapolis based manufacturer of women's health product line. Assets included plant and facilities, product lines, and intellectual property. 3. Negotiation and implementation of multiple rounds of venture capital financing in support of development and marketing operations in the growth and development of Adderall prior to sale to Shire Group plc. -

Restaurants in Lawrenceburg, IN

Restaurants in Lawrenceburg, IN Arby's 895 W Eads Pkwy, Lawrenceburg, IN 47025 Papa John's Pizza 1076 W Eads Pkwy, Lawrenceburg, IN 47025 Howie's Diner 1049 Eads Parkway E, Lawrenceburg, IN 47025 Pizza Hut 1054 W Eads Pkwy, Lawrenceburg, IN 47025 Hollywood & Grind 777 Hollywood Boulevard, Lawrenceburg, IN 47025 Tazza Rica Coffee House 42 E High St, Lawrenceburg, IN 47025 Snow Biz 24417 Green Meadow Dr, Lawrenceburg, IN 47025 McDonald's 24072 State Line Rd, Lawrenceburg, IN 47025 H-Bar 777 Hollywood Boulevard, Lawrenceburg, IN 47025 Celebrity Grill 777 Hollywood Boulevard, Lawrenceburg, IN 47025 Hafts Top of the Line Tavern 23903 State Line Rd, Lawrenceburg, IN 47025 Bob O's at the Levee 1 E High St, Lawrenceburg, IN 47025 Dunkin' Donuts 100 W. Eads Pkwy, Lawrenceburg, IN 47025 KFC 30 W Eads Pkwy, Lawrenceburg, IN 47025 Gus' Sports Bar 24071 State Line Rd, Lawrenceburg, IN 47025 Burger King 702 Lorey Ln, Lawrenceburg, IN 47025 Subway 1202 W Eads Pkwy, Lawrenceburg, IN 47025 Wendy's 449 W Eads Pkwy, Lawrenceburg, IN 47025 McDonald's 1041 W Eads Pkwy, Lawrenceburg, IN 47025 Little Caesars Pizza Tanners Creek Drive, Lawrenceburg, IN 47025 Gold Star Chili 1201 W Eads Pkwy, Lawrenceburg, IN 47025 Turn 2 Sports Bar & Restaurant 777 Hollywood Blvd, Lawrenceburg, IN 47025 Steak 'n Shake 861 West Eads Parkway, Lawrenceburg, IN 47025 Lawrenceburger 120 West Eads Parkway, Lawrenceburg, IN 47025 Whisky's Family Restaurant 334 Front St, Lawrenceburg, IN 47025 Los Primos Mexican Restaurant 24486 Stateline Road, Suite E, Lawrenceburg, IN 47025 Final -

Saint Bernard Professional Building 4903 Vine Street, Saint Bernard

For Sale 4903 Vine Street, Saint Bernard Professional Building – 5,394 square feet Saint Bernard, OH 45217 – In-place income – Centrally located multi-tenant office building in the heart of Todd Pease Saint Bernard +1 513 290 5408 [email protected] – Within walking distance of numerous amenities including dining, retail and entertainment jll.com – Well maintained professional office environment – Ample on-site parking available – Signage available on building – Sale price is $525,000 Amenities 562 1 1 5 3 2 1 10 3 2 6 4 2 7 75 5 5 71 7 8 9 6 3 4 4 Dining Shopping Entertainment • 1 Pizza Hut, •7 The Whole • 1 St. Bernard •4 CVS, Clifton • 1 St. Bernard Subway, Bowl, Ambar Square Market Swimming Pool Skyline Chili, India, Graeter’s Shopping •5 Norwood Plaza • 2 Avon Fields Golf Wendy’s Ice Cream Center, Dollar Course Tree •6 Rookwood • 2 Streetpops, •8 Lydia’s on Commons & • 3 Esquire Theatre Woodstone Ludlow, China • 2 Walgreens Pavilion • Cincinnati Zoo Creek Winery & Kitchen, 4 • 3 Kroger •7 Marshalls & Botanical Distillery Sitwell’s, Los Garden • 3 LaRosa’s Potrillos, • 5 Cintas Center Pizza, Wok Inn Arlin’s Bar & Express, St. Restaurant Bernard Pub, •9 Skyline Chili, Dairy Queen J. Gumbo’s, • 4 Popeye’s, White Dewey’s Pizza Castle 10 Sugar n’ Spice • 5 Gold Star Chili, Rally,’s McDonald’s, • 4903 Vine Street Frisch’s Big Boy • 6 Northside Yacht Club DISCLAIMER: Although information has been obtained from sources deemed reliable, neither Owner nor JLL makes any guarantees, warranties or representations, express or implied, as to the completeness or accuracy as to the information contained herein. -

Restaurants in Blue Ash Restaurant Name Address Abby Girl Sweets 4773 Glendale Milford Road, Cincinnati, OH 45242

Restaurants in Blue Ash Restaurant Name Address Abby Girl Sweets 4773 Glendale Milford Road, Cincinnati, OH 45242 Ando Japanese Restaurant 5889 Pfeiffer Road, Cincinnati, OH 45242 Anis Indian Cuisine 4122 Hunt Road, Cincinnati, OH 45236 Apple Spice Junction 4701 Creek Road, Cincinnati, OH 45242 Applebee's 10635 Tech Woods Circle, Cincinnati, OH 45242 Arbys 4951 Cornell Road, Cincinnati, OH 45242 Bangkok Terrace 4858 Hunt Road, Cincinnati, OH 45242 Blue Ash Cafe (in Rec Center) 4433 Cooper Road, Cincinnati, OH 45242 Blue Ash Chili 9565 Kenwood Road, Cincinnati, OH 45242 Bob Evans 5875 Pfeiffer Road, Cincinnati, OH 45242 Bonnie Lynn Bakeries 11179 Luschek Drive, Cincinnati, OH 45241 Brown Dog Café 5853 Pfeiffer Road, Cincinnati, OH 45242 Bruegger's Bagels 9590 Kenwood Road, Cincinnati, OH 45242 Buffalo Wild Wings 4550 Glendale-Milford Road, Cincinnati, OH 45242 Cafe Mediterranean 9525 Kenwood Road, Cincinnati, OH 45242 Cascade's Restaurant (in Embassy Suites) 4554 Lake Forest Drive , Cincinnati, OH 45242 Cazadores 4950 Cornell Road, Cincinnati, OH 45242 China Moon 4171 Hunt Road, Cincinnati, OH 45236 Chipotle 11255 Reed Hartman Highway, Cincinnati, OH 45242 City Barbeque 10375 Kenwood Rd, Cincinnati, OH 45242 Dairy Queen 4820 Cooper Road, Cincinnati, OH 45242 Decent Deli 11144 Kenwood Road, Cincinnati, OH 45242 DiBella's Subs 4645 Osborne Boulevard, Cincinnati, OH 45242 Donatos 9405 Kenwood Road, Blue Ash OH 45242 Dunkin Donuts 9188 Plainfield Road, Cincinnati, OH 45236 Durum Mediterranean 4764 Cornell Road, Cincinnati, OH 45242 El Pueblo -

Fairfield Chamber Restaurant Guide

FAIRFIELD CHAMBER RESTAURANT GUIDE Berd’s Grill & Bar 500 Wessel Drive – Fairfield Village Green 513-805-7250 Offers Carry Out / Open 11 am to 8 pm https://www.berdsgrillandbar.com/ Buffalo Wings & Rings 5486 Dixie Highway – Fairfield 513-829-9464 Carry out and delivery available Hours: Monday thru Thursday 11 am to 9 pm Friday and Saturday 11 am to 11 pm https://www.buffalowingsandrings.com/locations/fairfield Buffalo Joe’s 6130 Dixie Highway – Fairfield 513-829-8118 Carry Out available Hours: Monday to Friday 11 am to 8 pm Friday and Saturday 11 am to 10 pm Sunday 12 noon to 8 pm https://buffalojoesfairfield.com/ Caruso’s Ristorante & Bar 6765 Dixie Highway – Fairfield 513-8893210 Open for Carry Out http://carusoscincy.com/ Chick Fil – A 6305 S. Gilmore Road – Fairfield (in front of Meijer) 513-860-1918 Drive Thru Open 6:30 am to 10 pm Monday thru Saturday https://www.facebook.com/cfaffoh/ Gold Star Chili 4271 Hamilton Middletown Road – Fairfield Township Drive Thru Open Gold Star Chili 1286 Main Street – Hamilton 513-863-8956 Drive Thru Open Gold Star Chili 470 Nilles Road – Fairfield 513-858-3400 Drive Thru Open https://locations.goldstarchili.com/ll/US/OH/Fairfield/470-Nilles-Rd Gold Star Chili 1700 S. Erie – Ross 513-738-3338 Drive Thru Open Guthrie’s Chicken 6775 Dixie Highway, St E – Fairfield 513-860-4000 Drive Through is open and delivery available through Door Dash http://guthrieschicken.com/ Hot Head Burritos Nilles Road – Fairfield 513-858-4323 Open for Carry Out Delivery is available through Door Dash Customers can call ahead of time to order at 513-858-4323 and an employee will bring the food out to them.