Is There an African-American Graphic Novel?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS American Comics SETH KUSHNER Pictures

LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS LEAPING TALL From the minds behind the acclaimed comics website Graphic NYC comes Leaping Tall Buildings, revealing the history of American comics through the stories of comics’ most important and influential creators—and tracing the medium’s journey all the way from its beginnings as junk culture for kids to its current status as legitimate literature and pop culture. Using interview-based essays, stunning portrait photography, and original art through various stages of development, this book delivers an in-depth, personal, behind-the-scenes account of the history of the American comic book. Subjects include: WILL EISNER (The Spirit, A Contract with God) STAN LEE (Marvel Comics) JULES FEIFFER (The Village Voice) Art SPIEGELMAN (Maus, In the Shadow of No Towers) American Comics Origins of The American Comics Origins of The JIM LEE (DC Comics Co-Publisher, Justice League) GRANT MORRISON (Supergods, All-Star Superman) NEIL GAIMAN (American Gods, Sandman) CHRIS WARE SETH KUSHNER IRVING CHRISTOPHER SETH KUSHNER IRVING CHRISTOPHER (Jimmy Corrigan, Acme Novelty Library) PAUL POPE (Batman: Year 100, Battling Boy) And many more, from the earliest cartoonists pictures pictures to the latest graphic novelists! words words This PDF is NOT the entire book LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS: The Origins of American Comics Photographs by Seth Kushner Text and interviews by Christopher Irving Published by To be released: May 2012 This PDF of Leaping Tall Buildings is only a preview and an uncorrected proof . Lifting -

Illustrated Checklist Contemporary Works

Illustrated Checklist Curated by William Villalongo and Mark Thomas Gibson International Print Center New York Contemporary Works Derrick Adams (American, b.1970) Game Changing (Ace), 2015 Screenprint with gold leaf 30 x 22 inches Published by Lower East Side Printshop, New York. Edition: 16 Courtesy of the Artist and Lower East Side Printshop Image © 2016 Derrick Adams and Lower East Side Printshop Inc. Laylah Ali (American, b.1968) Untitled, from the Bloody Bits Series, 2004 Three mixed media drawings on paper 9 x 6 inches Courtesy of the Artist and Paul Kasmin Gallery Image © 2016 Laylah Ali Laylah Ali (American, b.1968) Untitled, from the Bloody Bits Series, 2004 Mixed media on paper 9 x 6 inches Courtesy of the Artist and Paul Kasmin Gallery Image © 2016 Laylah Ali Laylah Ali (American, b.1968) Untitled, from the Bloody Bits Series, 2004 Mixed media on paper 9 x 6 inches Courtesy of the Artist and Paul Kasmin Gallery Image © 2016 Laylah Ali Firelei Báez (Dominican, b.1980) The Very Eye of the Night, 2013 Pigmented linen on Abaca base sheet 58 x 31 x ¾ inches Courtesy of the Artist, Gallery Wendi Norris, San Francisco, and Dieu Donné, New York Image © 2016 Firelei Báez and Dieu Donné, New York Nayland Blake (American, b.1960) Bunny Group, Happiness, 1996–1997 Suite of four graphite and colored pencil drawings on paper 12 x 9 inches each Courtesy the Artist and Matthew Marks Gallery Image © 2016 Nayland Blake Robert Colescott (American, 1925 – 2009) Lock and Key (State I), 1989 Lithograph 42 x 30 inches Publisher: Tamarind Institute, Albuquerque Edition: 20 Collection of The #menelikwoolcockcollection: Zewditu Menelik, Aron Woolcock,Daniel Woolcock, and Adrian Woolcock Image © 2016 Robert Colescott Renee Cox (Jamaican, b.1960) Chillin with Liberty, 1998 Cibachrome print 60 x 40 x 2 inches Edition: 3 Courtesy of the Artist Image © 2016 Renee Cox William Downs (American, b.1974) The power of fantastic, 2013 Aquatint and etching 24 x 16 inches Published by the Artist. -

|||GET||| Damage Control 1St Edition

DAMAGE CONTROL 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE Lisa Renee Jones | 9781250083838 | | | | | Damage Control (comics) Hoag hints at a secret past with Cage. Maybe the concept doesn't hold up to such a voluminous collection, and is better handled in smaller bites. Damage Control 1st edition and now needs the good doctor to cough up the Damage Control 1st edition. Published Jun by Marvel. Art by Ernie Colon. And a notary. Spider-Man remains trapped inside. Damage Control is a fictional construction company appearing in American comic books published by Marvel Comics. Issue ST. Sign In Don't Damage Control 1st edition an Damage Control 1st edition Would have been better if more episodic. During the reconstruction, a strange side-effect of one of the Hulk's destroyed machines causes the Chrysler Building to come to life. And even that first miniseries did have its moments, like Wolverine getting a pie in the face, and the Danger Room creating a tiny robot Groucho Marx. John Wellington. Start Your Free Trial. Published Aug by Marvel. Damage Control 1st edition his battle against Declun and Damage Control, which includes destroying many D. It's just how generic he is without any real motivation or interesting characteristics. Retrieved October 3, Read a little about our history. I picked this collection up to read more of the inanity, and was taken back briefly to the novelty of it all. Several of the employees meet and discuss the problem with other cosmic entities, such as Galactus and Lord Chaos. It's also not clear why Robin Chapel is so frequently sidelined. -

Jenette Kahn

Characters TM & © DC Comics. All rights reserved. 0 6 No.57 July 201 2 $ 8 . 9 5 1 82658 27762 8 THE RETRO COMICS EXPERIENCE! JENETTE KAHN president president and publisher with former DC Comics An in-depth interview imprint VERTIGO DC’s The birth of ALSO: Volume 1, Number 57 July 2012 Celebrating The Retro Comics Experience! the Best Comics of the '70s, '80s, '90s, and Beyond! EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Michael Eury PUBLISHER John Morrow DESIGNER Rich J. Fowlks EISNER AWARDS COVER DESIGNER 2012 NOMINEE Michael Kronenberg PROOFREADER Rob Smentek SPECIAL THANKS BEST COMICS-RELATEDJOURNALISM Karen Berger Andy Mangels Alex Boney Nightscream BACK SEAT DRIVER: Editorial by Michael Eury . .2 John Costanza Jerry Ordway INTERVIEW: The Path of Kahn . .3 DC Comics Max Romero Jim Engel Bob Rozakis A step-by-step survey of the storied career of Jenette Kahn, former DC Comics president and pub- Mike Gold Beau Smith lisher, with interviewer Bob Greenberger Grand Comic-Book Roy Thomas Database FLASHBACK: Dollar Comics . .39 Bob Wayne Robert Greenberger This four-quarter, four-color funfest produced many unforgettable late-’70s DCs Brett Weiss Jack C. Harris John Wells PRINCE STREET NEWS: Implosion Happy Hour . .42 Karl Heitmueller Marv Wolfman Ever wonder how the canceled characters reacted to the DC Implosion? Karl Heitmueller bellies Andy Helfer Eddy Zeno Heritage Comics up to the bar with them to find out Auctions AND VERY SPECIAL GREATEST STORIES NEVER TOLD: The Lost DC Kids Line . .45 Alec Holland THANKS TO Sugar & Spike, Thunder and Bludd, and the Oddballs were part of DC’s axed juvie imprint Nicole Hollander Jenette Kahn Paul Levitz BACKSTAGE PASS: A Heroine History of the Wonder Woman Foundation . -

BCALA X GNCRT

Children’s Comics, The Little Rock Nine and the When the Beat Was Born: DJ Fight for Equal Education Kool Herc and the Creation of by Gary Jeffrey Graphic Novels & Hip Hop Art by Nana Li by Laban Carrick Hill Picture Books This graphic nonfiction follows the Art by Theodore Taylor III African American students chosen to The beginnings of hip hop in the 1970s integrate a high school in Little Rock, The Adventures of and 1980s is introduced through this Arkansas, after the U.S. Supreme Court Sparrowboy biography of DJ Kool Herc, starting on struck down school segregation. the island of Jamaica and moving to the by Brian Pinkney Ages 9-12 Bronx, NY. A paperboy discovers he has Ages 6-10 superpowers like his hero Falconman. Ages 0-8 New Kid by Jerry Craft Woke Baby Black Heroes of the Wild When seventh-grader Jordan Banks by Mahogany Browne Art by Theodore Taylor III West: Featuring Stagecoach starts attending a private school that is primarily white, he has to learn how to Woke babies are up early. Woke babies Black History in Its Own Mary, Bass Reeves, and Bob raise their fists in the air. Woke babies navigate microaggressions, tokenism, Words cry out for justice. Woke babies grow Lemmons and not fitting in. New Kid won the by Ronald Wimberly up to change the world. This lyrical and by James Otis Smith Coretta Scott King Award (2020) and is This is Black history as told through empowering book is both a celebration Introduction by Kadir Nelson the first graphic novel to win the quotes from the Black men and women of what it means to be a baby and what This nonfiction graphic novel brings to Newbery Medal Award (2020). -

Mason 2015 02Thesis.Pdf (1.969Mb)

‘Page 1, Panel 1…” Creating an Australian Comic Book Series Author Mason, Paul James Published 2015 Thesis Type Thesis (Professional Doctorate) School Queensland College of Art DOI https://doi.org/10.25904/1912/3741 Copyright Statement The author owns the copyright in this thesis, unless stated otherwise. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/367413 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au ‘Page 1, Panel 1…” Creating an Australian Comic Book Series Paul James Mason s2585694 Bachelor of Arts/Fine Art Major Bachelor of Animation with First Class Honours Queensland College of Art Arts, Education and Law Group Griffith University Submitted in fulfillment for the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Visual Arts (DVA) June 2014 Abstract: What methods do writers and illustrators use to visually approach the comic book page in an American Superhero form that can be adapted to create a professional and engaging Australian hero comic? The purpose of this research is to adapt the approaches used by prominent and influential writers and artists in the American superhero/action comic-book field to create an engaging Australian hero comic book. Further, the aim of this thesis is to bridge the gap between the lack of academic writing on the professional practice of the Australian comic industry. In order to achieve this, I explored and learned the methods these prominent and professional US writers and artists use. Compared to the American industry, the creating of comic books in Australia has rarely been documented, particularly in a formal capacity or from a contemporary perspective. The process I used was to navigate through the research and studio practice from the perspective of a solo artist with an interest to learn, and to develop into an artist with a firmer understanding of not only the medium being engaged, but the context in which the medium is being created. -

Abrams Books Joins Comic-Con@Home 2020

Contacts: Maya Bradford, Senior Publicist, [email protected] Hallie Patterson, Director, Children’s Publicity, [email protected] ABRAMS BOOKS JOINS COMIC-CON@HOME 2020 New York, July 16, 2020—ABRAMS will be featured at Comic-Con@Home, a free virtual event created by the organizers of San Diego Comic-Con that will include virtual panels and an online exhibit hall. The celebration will take place July 22–26, 2020, and authors, artists, and staff representing a wide array of ABRAMS’s imprints, including Abrams ComicArts, Abrams, Amulet Books, and Abrams Appleseed, will participate in eight virtual panels. ABRAMS titles, including exclusive editions, signed copies, and exciting giveaways like early galleys, will also be available in the online Exhibit Hall, at Abrams booth #1216. ABRAMS is also proud to celebrate five Eisner nominations this year. EXCLUSIVE EDITIONS Avatar, The Last Airbender: The Shadow of Kyoshi Return to the epic saga from the world of Avatar: The Last Airbender with the eagerly anticipated sequel to the New York Times bestseller Avatar, The Last Airbender: The Rise of Kyoshi. This exclusive edition of the new novel features this stunning variant cover and is available only through Mysterious Galaxy during Comic-Con@Home. https://www.mystgalaxy.com/shadow-kyoshi-comic-con-exclusive-edition My Mighty Marvel First Book Boxed Set A limited run of exclusive Con Edition Boxed Sets will be available through Mysterious Galaxy with My Mighty Marvel First Book: The Amazing Spider-Man and My Mighty Marvel First Book: Captain America, the first two books in the series of collectible board books that introduce the world’s greatest heroes as drawn by the world’s greatest creators. -

Warren Ellis Frankenstein's Womb Gn (Ogn) H MMW THOR V

H UNIVERSAL WAR ONE V. 1 HC H POWERS V. 12 TPB collects #1-3, $25 collects #25-30, $20 H M ADVS HULK V. 4 DIGEST H MMW AVENGERS V. 8 HC collects #13-16, $9 collects #69-79, $55 H M ADVS SPIDEY V. 11 DIGEST H MMW atlas era STRANGE TALES v.2 HC collects #41-44, $9 collects #11-20, $55 H ANITA BLACK VH GP V. 2 TPB Warren Ellis Frankenstein's Womb Gn (ogn) H MMW THOR V. 8 HC collects #7-12, $16 by Warren Ellis & Marek Oleksicki It began a few months earlier when, en route through Ger- H collects #163-172, $55 SPIDEY BND V . 2 TPB many to Switzerland, Mary, her future husband Percy Shelley, and her stepsister Clair Clair- H SECRET WARS OMNIBUS V. 2 HC collects #552-558, $20 mont approached a strange castle. And she was never the same again - because something H collects EVERYTHING!! REALLY, $100 CABLE V. 1 TP was haunting that tower, and Mary met it there. Fear, death and alchemy - the modern age is H ULTIMATE ORIGINS HC collects #1-5, $15 created here, in lost moments in a ruined castle on a day never recorded. collects #1-5, $25 H HEDGE KNIGHT 2 S. SWORD TPB H NOVA V. 1 HC collects #1-6, $16 Eureka #1 (4 issues) collects #1-12 & ANN 1, $35 H INFINITY CRUSADE V. 1 TPB by Andrew Cosby, Brendan Hay & Diego Barreto TV's smash sci-fi hit comes to BOOM! In what H ULTIMATES 3 V. -

THE ROLE of RACE and ETHNCITY in FANDOM a Thesis By

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Texas A&M Repository NERDS OF COLOR ASSEMBLE: THE ROLE OF RACE AND ETHNCITY IN FANDOM A Thesis by SIMON SEBASTIAH WILLIAMS Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Approved by: Co-chairs of Committee, Sarah Gatson Joseph Jewell Committee Member, Corliss Outley Head of Department, Jane Sell December 2012 Major Subject: Sociology Copyright 2012 Simon Sebastiah Williams ABSTRACT With shows such as Big Bang Theory and the increased mainstreaming of San Diego Comic-con, now more than ever before, it is acceptable to be a “nerd”. The question now becomes what efforts are being made to appeal to fans of color in traditional “nerd” activities, specifically comic books (this can include television shows and movies based on comic book characters), anime, and science fiction. Throughout the decades, there have been various attempts to have a discourse about the lack of diversity in nerd culture, both among its creators and characters from various properties considered beloved to nerds. Only, at the time of this writing, in recent years does there seem to be an increase among fans of color discussing these issues in the world at large, and not just in their own social group(s). This research will discover how minority fans feel about representation, or lack thereof, in the three above fandom. It will examine how minority fans feel about specific instants involving race and ethnicity in fandom from the past year. -

March 2017 NASFA Shuttle

Te Shutle March 2017 The Next NASFA Meeting is 6:30P Saturday 11 March 2017 at the Regular Location Concom Meeting 3P at the Church, 11 March 2017 The new location will be 446 Jeff Road NW, about a mile d Oyez, Oyez d from the current location. See the map on page 10 of this issue. ! CONCOM MEETINGS The next NASFA Meeting will be 11 March 2017, at the The next Con†Stellation XXXV Concom Meeting will be at regular meeting location—the Madison campus of Willow- 3P on 11 March 2017—the same day as this month’s NASFA brook Baptist Church (old Wilson Lumber Company building) meeting. It will be at the church. There will be a dinner break at 7105 Highway 72W (aka University Drive). PLEASE between the concom and the club meeting. NOTE this is a week earlier than the usual weekend due to a In general, future Con†Stellation XXXV Concom Meetings conflict with Huntsville Comic & Pop Culture Expo. will be at 3P on the same day as the club meeting, but with at Please see the map at right if you need help finding it the church. PLEASE NOTE that this will (barring a last-second switch) be the last meeting at this location. The church is scheduled to move before the end of March. Road Jeff Kroger MARCH PROGRAM The March program will be a game of Fannish Feud, pre- sented by Kevin “Fritz” Fotovitch. US 72W MARCH ATMM (aka University Drive) At press time, there is no volunteer to host the March After- The-Meeting Meeting. -

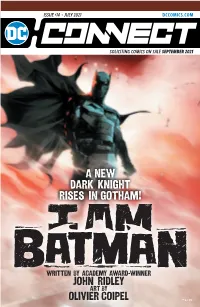

A New Dark Knight Rises in Gotham!

ISSUE #14 • JULY 2021 DCCOMICS.COM SOLICITING COMICS ON SALE SEPTEMBER 2021 A New Dark Knight rises in Gotham! Written by Academy Award-winner JOHN RIDLEY A r t by Olivier Coipel ™ & © DC #14 JULY 2021 / SOLICITING COMICS ON SALE IN SEPTEMBER WHAT’S INSIDE BATMAN: FEAR STATE 1 The epic Fear State event that runs across the Batman titles continues this month. Don’t miss the first issue of I Am Batman written by Academy Award-winner John Ridley with art by Olivier Coipel or the promotionally priced comics for Batman Day 2021 including the Batman/Fortnite: Zero Point #1 special edition timed to promote the release of the graphic novel collection. BATMAN VS. BIGBY! A WOLF IN GOTHAM #1 12 The Dark Knight faces off with Bigby Wolf in Batman vs. Bigby! A Wolf in Gotham #1. Worlds will collide in this 6-issue crossover with the world of Fables, written by Bill Willingham with art by Brian Level. Fans of the acclaimed long-running Vertigo series will not want to miss the return of one of the most popular characters from Fabletown. THE SUICIDE SQUAD 21 Interest in the Suicide Squad will be at an all-time high after the release of The Suicide Squad movie written and directed by James Gunn. Be sure to stock up on Suicide Squad: King Shark, which features the breakout character from the film, and Harley Quinn: The Animated Series—The Eat. Bang. Kill Tour, which spins out of the animated series now on HBO Max. COLLECTED EDITIONS 26 The Joker by James Tynion IV and Guillem March, The Other History of the DC Universe by John Ridley and Giuseppe Camuncoli, and Far Sector by N.K. -

‚X Marks the Spot╎: Urban Dystopia, Slum Voyeurism and Failures of Identity in District X

JUCS 2 (1+2) pp. 35–55 Intellect Limited 2015 Journal of Urban Cultural Studies Volume 2 Numbers 1 & 2 © 2015 Intellect Ltd Article. English language. doi: 10.1386/jucs.2.1-2.35_1 Martin Lund Linnaeus University and the CUNY Graduate Center ‘X marks the spot’: urban dystopia, slum voyeurism and failures of identity in District X abstract Keywords This article studies the ‘imaginative mapping’ of a real-world neighbourhood in one Marvel Comics comic book series: lower Manhattan’s Alphabet City in writer David Hine and artists mutantcy David Yardin and Lan Medina’s District X (July 2004–January 2006). In contrast blackness to a long-standing claim to ‘realism’ in Marvel’s use of New York City, this article homelessness argues that the real Alphabet City – at the time a contested and rapidly gentrify- identity formation ing neighbourhood – is nowhere to be found in District X, replaced by a voyeuris- slums tic fabrication, a sensationalistic node of concentration for middle-class fears about Alphabet City urban decline and blight amid prosperity and contemporary discourses about drugs, urban representation crime and homelessness that reproduces long-standing cultural representations of the neighbourhood as different and inferior. In doing so, the series polices a bound- ary of identity, empathy and imagination and tells readers that force in favour of clearing out radical difference in the neighbourhood and making it into a space fit for ‘normal’ people is natural, rational and logical and in the best interest even of those who might be displaced by gentrification, disproportionately incarcerated in the name of ‘law and order’, or put at risk of their lives in dangerous shelters.