Mesa Verde National Park Hearing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyrighted Material

20_574310 bindex.qxd 1/28/05 12:00 AM Page 460 Index Arapahoe Basin, 68, 292 Auto racing A AA (American Automo- Arapaho National Forest, Colorado Springs, 175 bile Association), 54 286 Denver, 122 Accommodations, 27, 38–40 Arapaho National Fort Morgan, 237 best, 9–10 Recreation Area, 286 Pueblo, 437 Active sports and recre- Arapaho-Roosevelt National Avery House, 217 ational activities, 60–71 Forest and Pawnee Adams State College–Luther Grasslands, 220, 221, 224 E. Bean Museum, 429 Arcade Amusements, Inc., B aby Doe Tabor Museum, Adventure Golf, 111 172 318 Aerial sports (glider flying Argo Gold Mine, Mill, and Bachelor Historic Tour, 432 and soaring). See also Museum, 138 Bachelor-Syracuse Mine Ballooning A. R. Mitchell Memorial Tour, 403 Boulder, 205 Museum of Western Art, Backcountry ski tours, Colorado Springs, 173 443 Vail, 307 Durango, 374 Art Castings of Colorado, Backcountry yurt system, Airfares, 26–27, 32–33, 53 230 State Forest State Park, Air Force Academy Falcons, Art Center of Estes Park, 222–223 175 246 Backpacking. See Hiking Airlines, 31, 36, 52–53 Art on the Corner, 346 and backpacking Airport security, 32 Aspen, 321–334 Balcony House, 389 Alamosa, 3, 426–430 accommodations, Ballooning, 62, 117–118, Alamosa–Monte Vista 329–333 173, 204 National Wildlife museums, art centers, and Banana Fun Park, 346 Refuges, 430 historic sites, 327–329 Bandimere Speedway, 122 Alpine Slide music festivals, 328 Barr Lake, 66 Durango Mountain Resort, nightlife, 334 Barr Lake State Park, 374 restaurants, 333–334 118, 121 Winter Park, 286 -

Mesa Verde National Park

MESA VERDE NATIONAL PARK Additional copies of this portfolio are obtainable from the publisher (Mesa Verde Company, Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado) at 500 per copy in the Park, or 600 postpaid to any point in the United States. MESA VERDE In the colorful northern Navajo country, overlooking the "four corners" where Arizona, New Mexico, Utah, and Colorado meet, rises a forested flat-topped mountain which early Spanish explorers called Mesa Verde—the green tableland. Deep canyons countersunk into the heart of this wide plateau hide the deserted cliff cities of a remarkable stone age civilization that flourished here a thousand years ago. When the great ruins of Mesa Verde .were discovered in the late 80's and the early 90's, the story of the vanished race that lived in these spectacular ruins was shrouded in mystery. A large part of that mystery still exists—but now, bit by bit, archaeologists are piecing together fragments of information which reconstruct a picture of the ancient people. We know much about their physical appearance, their daily life and culture, and the events that led to abandoning their impregnable strongholds betw 1276 and 1295 A.D.-but that story will be told in detail by the ranger guides whelPyou visit Mesa Verde National Park. DESCRIPTIVE DETAILS This Mesa Verde portfolio has been prepared with a view to making each Climbing to Balcony House Ruin (Page 7) individual picture suitable for framing. For this reason the titles have been Ladders add zest to the exploration of many of Mesa Verde's cliff dwellings. -

Death by a Thousand Cuts

Colorado Colorado by the numbers1 730,000 acres of park land 5,811,546 visitors in 2012 National Park Service $319,000,000 economic benefit from National Park tourism in 2011 National Park Units in Colorado 10 threatened and endangered species in National Parks 6,912 archeological sites in National Parks Sand Dunes National Park Rocky Mountain National Park Blog.ymcarockies.org Empoweringparks.com Colorado National Park Service Units2 Bent's Old Fort Historic Site Hovenweep Monument Black Canyon of the Gunnison Park Mesa Verde Park Cache La Poudre River Corridor Old Spanish Historic Trail California Historic Trail Pony Express Historic Trail Colorado Monument Rocky Mountain Park Curecanti Recreation Area Sand Creek Massacre Historic Site Dinosaur Monument Santa Fe Historic Trail Florissant Fossil Beds Monument Yucca House Monument Great Sand Dunes Park & Preserve 1 http://www.nps.gov/state/co/index.htm?program=parks 2 http://www.nps.gov/state/co/index.htm?program=parks Colorado Boasting both breathtaking Rocky Mountain National Park habitats and remarkable ecosystem di- versity, the national parks of Colorado provide a myriad of benefits to visitors and the local environment alike. Sand Dunes National Park showcases the result of the unique act of colliding winds blowing through the mountain ranges of the area, resulting in the tallest sand dunes found any- where in the country.3 The dramatic and majestic The Haber Motel peaks of the Rocky Mountains charac- terize the rugged and resilient nature of Colorado’s wilderness. Few places in the country boast as much wildlife and ecosystem diversity as Rocky Mountain Park, further illustrating the critical importance of protecting this iconic land- scape.4 Effects of Sequester Cuts At Mesa Verde National Park, the sequester cuts led to a budget reduction of $335,000. -

October 1, 2009

National Park Service Archeology Program U.S. Department of the Interior December 2014 Archeology E-Gram NPS NEWS Passing of Pat Parker Patricia Parker, Chief of the NPS American Indian Liaison Office died on December 16, 2014, in Silver Spring, Maryland. Pat held a Ph.D. in anthropology from the University of Pennsylvania and studied under Ward Goodenough. Her dissertation was based on fieldwork in Chuuk, one of the four states of the Federated States of Micronesia. She also co-directed the Tonaachaw Historic District ethno-archeological project, also in Chuuk, resulting in the first archeological monograph published partly in Chuukese. Pat was instrumental in securing a homeland for the Death Valley Timbi-sha Shoshone Tribe and in resolving other conflicts between tribes and Native Hawaiian organizations, and the Federal government. With Charles Wilkenson of Colorado State University, she developed and presented classes in the foundations of Indian law, designed to help government officials understand the special legal, fiduciary, and historical relationships between tribes and the U.S. government. She was also a co-author of National Register Bulletin 38- Guidelines of Evaluating and Documenting Traditional Cultural Properties, insisting that places of traditional interest to tribes and other communities must be respected by Federal agencies in their planning. At her death, she was involved in long-term efforts to create an Indian-administered national park on the South Unit of Badlands NP, and to finalize regulations facilitating tribal access to traditional plant resources in national parks. Pat’s family asks for donations to the Native American Rights Fund (http://www.narf.org/) in lieu of flowers. -

New Discoveries Nearcahokia

THE ROLE OF ROCK ART • SEEING THE BEST OF THE SOUTHWEST • UNDERWATER ARCHAEOLOGY SPRING 2011 americanamericana quarterly publication of The Archaeological Conservancyarchaeologyarchaeology Vol. 15 No. 1 NEW DISCOVERIES NEAR CAHOKIA $3.95 SPRING 2011 americana quarterly publication of The Archaeological Conservancyarchaeology Vol. 15 No. 1 COVER FEATURE 12 THE BEGINNINGS OF URBANISM? BY SUSAN CABA Was Cahokia a prehistoric metropolis? 24 The discovery of a large adjacent community has convinced some archaeologists that it was. 19 THE STORIES UNDER THE SEA BY AMY GREEN A maritime archaeology program is uncovering details of the history of St. Augustine, America’s oldest port city. 24 THE BEST OF THE SOUTHWEST BY NANCY ZIMMERMAN Come along on one of the Conservancy’s most popular tours. 32 REVEALING THE ROLE OF ROCK ART BY LINDA MARSA MER Researchers in California are trying to determine L PAL L E the purpose of these ancient images. A H C MI 7 38 THE STORY OF FORT ST. JOSEPH BY MICHAEL BAWAYA The investigation of a 17th-century French fort in southwest Michigan is uncovering the story of French colonialism in this region. 44 new acquisition A PIECE OF CHEROKEE HISTORY The Conservancy signs an option for a significant Cherokee town site. 46 new acquisition PRESERVING AN EARLY ARCHAIC CEMETERY The Sloan site offers a picture of life and death more than 10,000 years ago. 47 new acquisition THE CONSERVANCY PARTNERS TO OBTAIN NINTH WISCONSIN PRESERVE The Case Archaeological District contains several prehistoric sites. 48 new acquisition A GLIMPSE OF THE MIDDLE ARCHAIC PERIOD The Plum Creek site could reveal more information about this time. -

The Folsom Point

The Folsom Point Northern Colorado Chapter / Colorado Archaeological Society Volume 21, Issue 5 Volunteer Archaeologist Opportunities May 2006 May 17 (Wednesday). 7:00 p.m. Ben Waldren (deceased) of Oxford University, Special points of interest: Delatour Room, Fort Collins Main Library, have helped to re-write the understanding • May is Colorado Archaeology 201 Petersen. of human occupation in the western and Historic Preservation Month. Mediterranean. Before human occupation, See Page 3 for list of selected The blue Mediterranean, olive trees, and events. the island contained three mammals: a sheep bells in the distance. It's a tough • May 15—Program Meeting: job but somebody's got to do it. goat/antelope called a myotragus, a “Opportunities for Volunteer rodent and an insect eater. Archaeologists” by Lucy Burris To tie in with Historic It had long been held that • May 20—Field trip to Pawnee Preservation Month, our myotragus went extinct Grasslands with Robin Roberts. meeting in May will be See Page 2 for details. before humans arrived but on volunteering. Part Waldren's careful • May 30—June 27 American West travelogue, part show Program Series. See Page 4. excavations showed that far and tell, part get the • July 24-28—Volunteers needed to from this being the case, the itchy feet going, Lucy help Robin Roberts survey and myotragus had been record homestead sites on the Burris will talk about partially domesticated and Pawnee. See Page 2 for details. being an archaeological went extinct as their • “Awakening Stories” Continues volunteer. How to get started, where to primary food source (a bush toxic to sheep at the Greeley History Museum find out about opportunities, and how to through August 31. -

Mesa Verde National Park Foundation Document Overview

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE • U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Foundation Document Overview Mesa Verde National Park Colorado Contact Information For more information about the Mesa Verde National Park Foundation Document, contact: [email protected] or 970-529-4465 or write to: Superintendent, Mesa Verde National Park, PO Box 8, Mesa Verde, CO 81330-0008 Purpose Significance Significance statements express why Mesa Verde National Park resources and values are important enough to merit national park unit designation. Statements of significance describe why an area is important within a global, national, regional, and systemwide context. These statements are linked to the purpose of the park unit, and are supported by data, research, and consensus. Significance statements describe the distinctive nature of the park and inform management decisions, focusing efforts on preserving and protecting the most important resources and values of the park unit. • Mesa Verde National Park is an example of thousands of years of human interaction with the environment, reflected in a remarkable density and variety of sites related to the Ancestral Pueblo occupation of the Southwest. • Mesa Verde National Park is important in the history and heritage of the tribes and pueblos of Mesa Verde, and to many others for whom multigenerational ties exist. • Mesa Verde National Park protects and preserves more than 5,000 archeological sites. These include more than 600 alcove sites, some of the best known and most accessible cliff dwellings in North America. • In the early 1900s, visitors to the Mesa Verde area were captivated by the remarkable cliff dwellings they observed, and became vocal advocates for park establishment. -

Trip Planner U.S

National Park Service Trip Planner U.S. Department of the Interior World Heritage Site The official newspaper of Mesa Verde National Park Mesa Verde 2007 Edition Making the Most of Your Time To get the most out of your visit to Mesa Verde, stop first at the Far View Visitor Center Half Day (open spring through fall only, 8:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m.) or the Chapin Mesa Museum (open •Far View Visitor Center (15 miles from park entrance) for information and orientation. all year). From the park entrance on U.S. Hwy 160, the Far View Visitor Center is located •Chapin Mesa Museum and self-guided tour of Spruce Tree House -or- drive the Mesa Top 15 miles (25 km) into the park. Chapin Mesa Archeological Museum, Park Headquarters, Loop Road (6-mile loop). and Spruce Tree House are 21 miles (34 km) from the park entrance. The route into the One Day park is a steep, narrow, winding mountain road. Depending on weather, traffic, and road •Far View Visitor Center to purchase tickets for Cliff Palace or Balcony House guided tours. construction, plan at least two hours just to drive into and out of the park. The drive is •Cliff Palace Loop Road (If you plan to visit Cliff Palace or Balcony House,make sure you scenic with pull-offs and overlooks that provide spectacular views into four states. The have your tickets first.) •Chapin Mesa Museum and view the park film, self-guided tour of Spruce Tree House and elevations in the park range from 6,900 feet to 8,572 feet. -

(Pdf) Download

NEWSLETTER OF THE COLORADO ROCK ART ASSOCIATION (CRAA) A Chapter of the Colorado Archaeological Society http://www.coloradorockart.org September 2016 Volume 7, Issue 7 As Colorado Rock Art Association members you are also Inside This Issue members of the Colorado Archaeological Society. The Colorado Archaeological Society is having its annual Field Trips …………..….… page 2 meeting October 7-10 in Grand Junction. There will be many field trips, including many that include rock art. In addition, there will be lectures aimed at the avocational Feature Article: The audience. CRAA is sponsoring noted rock art specialist Mu:kwitsi/Hopi (Fremont) Sally Cole. In addition, the Keynote speaker is Steve Lekson who will talk about Chaco Canyon. Steve Lekson is abandonment and Numic a noted Southwest Archaeologist. He is a professor at Immigrants into Nine Mile Colorado University and a curator at the University of Canyon as depicted in the Colorado Museum of Natural History. He has written several books including Chaco Meridian: One Thousand rock art. Years of Political Power in the Ancient Southwest (second ………………………………….…..page 4 edition)(2015) and A History of the Ancient Southwest (2009). Please consider signing up for the annual meeting. Information on how to do sign up is in this issue. Sign up for CAS Annual meeting and other conferences This month’s feature article is part 2 of The Mu:kwitsi/Hopi …………………………….…..…. page 3 (Fremont) abandonment and Numic Immigrants into Nine Mile Canyon as depicted in the rock art, written by CRAA member Carol Patterson. PAAC Fall Classes The new Assistant State Archaeologist Chris Johnston has …………………………………page 12 announced PAAC Classes for this fall around the state. -

Ecoregional Design at Mesa Verde National Park

Phantom Ranch, GRand canyon, Arizona, Lummis house, Los anGeLes, caLifoRnia, shaeffeR house, new mexico, ElectRa Lake, coLoRado, tucumcaRi, new mexico, Fred haRvey RaiL stations By RoBeRt G. Bailey PhotoGRaPhy By alexandeR VeRtikoff hen the national Park Service was estab- structures at Colorado’s Mesa Verde National Park. Yet, w lished in 1916, the new agency inherited an rather than follow tradition, principal designers husband architectural legacy developed by private interests, par- and wife Jesse and Aileen Nusbaum became the first to ticularly the railroads. This legacy included Northern incorporate surrounding ecological themes into the de- Pacific’s Old Faithful Inn in Yellowstone and Santa Fe’s sign of a National Park structure, not only setting a new El Tovar at the south rim of the Grand Canyon, both built precedent, but creating a clear sense of design purpose that in the Swiss Chalet–Norway Villa tradition. This his- would contribute significantly to the nation’s architectural torical precedent—borrowing attractive yet incongruous heritage. design themes from the Old World with little regard for As the first National Park Service (NPS) building to the natural setting—was inherited by the designers of the be designed with a sense of its place, the superintendent’s a sense of Place: Ecoregional Design at Mesa Verde National Park 62 63 Phantom Ranch, GRand canyon, Arizona, Lummis house, Los anGeLes, caLifoRnia, shaeffeR house, new mexico, ElectRa Lake, coLoRado, tucumcaRi, new mexico, Fred haRvey RaiL stations The T-shaped doorway was inspired by ancienT anasazi dwellings in The souThwesT, such as pueblo boniTo in chaco canyon naTional hisTorical park, new Mexico. -

Durango, Silverton & Ouray August 9-14, 2020 This 6-Day and 5-Night

Durango, Silverton & Ouray August 9-14, 2020 This 6-day and 5-night springtime tour to the mountains is filled with fantastic scenery and unique history – if you like both, this itinerary will suit you fine. We experience Mesa Verde National Park, ride the Durango-Silverton Narrow Gauge Railroad, travel on jeeps in the Rockies and stay in the historic La Posada Hotel. Activity Level: Moderate Highlights: • Mesa Verde National Park • Ouray Hot Springs • Durango-Silverton Narrow Gauge Railroad • Jeep tour in the Rockies • Million Dollar Highway • Stay at historic La Posada in Winslow Day 1 We depart Tucson and journey north through juniper-covered hills to Salt River Canyon within the Tonto National Forest. After a lunch stop in the White Mountains we head to Gallup, New Mexico for a welcome dinner at the historic El Rancho Hotel and our overnight stay at Springhill Suites. (L,D) Day 2 This morning we explore Mesa Verde National Park. A UNESCO Heritage Site, Mesa Verde NP is the largest archaeological preserve in the United States. It’s known for its well-preserved Ancestral Puebloan cliff dwellings, notably the huge Cliff Palace, thought to be the largest cliff dwelling in North America, rock art and panoramic canyon views. We then head east to Durango, Colorado, where we stay overnight at the prominent downtown landmark, the Historic Strater Hotel, built in 1887, and enjoy dinner in another historic landmark, The Palace. (B,D) Day 3 Today we board a closed car on the Durango-Silverton Narrow Gauge Railroad. This 1880’s vintage train and railroad route was originally built to carry supplies and people to the fold and silver ore from the mines in the San Juan Mountains. -

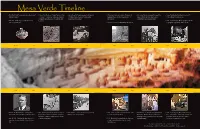

Mesa Verde National Park Timeline

Mesa Verde Timeline • 500s AD – First pit houses and signs of permanent • 1100 – 1300 – The Classic Pueblo Period saw the • 1300 – Ancestral Puebloan people had migrated • 1859 – Great Colorado Goldrush. Professor J.S. • 1880 – Chief Ouray and delegation negotiate • 1888 – The Weatherill brothers discover Cliff habitation appear construction of extensive complexes of pueblos. from Mesa Verde. There are many possible Newberry makes the first known mention of treaty in Washington D.C. that includes Palace while tracking livestock. Cliff dwellings number over 600 within the park reasons for the migration. Mesa Verde. establishment of reservation lands. • Mid-700s – People began grouping houses to boundaries. • 1889 – Activist Virginia McClurg begins a decade- form compact villages. • 1870s - 80s – Several cliff dwellings discovered. long fight to designate the National Park. 500 AD 700 900 1100 1300 1850 1860 1870 1880 1890 1906 1908 1910 1930 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2006 • 1906 The Ute Mountain Utes exchange Mesa • 1908 – Building stabilization and archaeological • 1910s onward – Tourists and archaeologists begin • 1976 - Lands are added to the National Park with • 2003/4 Forest fires brought on by drought burn • 2006 – After 100 years, Mersa Verde National Verde lands forother lands in Southwest Colorado. preservation activities are undertaken to protect visiting in increasing numbers. new wilderness designations. thousands of National Park acres, but leave Park celebrates the continued preservation and sites. These activities continue to date and will dwellings undamaged. The process of regrowth protection of these irreplaceable cultural • June 29, 1906 – President Theodore Roosevelt continue into the future. • 1978 - Mesa Verde National Park is declared one is well underway.