Protection Op Minority Interests Under the Indian Constitution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

District Superintendent of Education, Palamu

DISTRICT SUPERINTENDENT OF EDUCATION, PALAMU MASTER GRADATION LIST (2020) Social Educational GRADE (I / II / III Sl# Name School Block Gender DOB Appointed Subject DOJ in Service Appointment Type Address Category Qualification / IV / VII) MOHAMMAD MADRASATUL ISLAM KUDAGA 1 CHAINPUR (200210) Male BC 12/05/1962 Urdu 25/09/1980 Elementary (1 TO 8) PATRATU,SARJU,GARU, LATEHAR JAMALUDIN KALAN NEZMUDDIN AHAMAD MADRASATUL ISLAM KUDAGA 2 CHAINPUR (200210) Male BC 03/02/1962 Urdu 01/10/1980 Elementary (1 TO 8) SHAHPUR, CHAINPUR, PALAMU ANSARI KALAN BRIJ MOHAN Hussainabad 3 RAJKIYEKRIT MS DEORI KHURD Male SC 01/02/1961 All Subject 04/02/1981 Elementary (1 TO 8) Japla Dharhara Rambigha CHOUDHARY (200204) MADRASATUL ISLAM KUDAGA 4 MD FASIHUDDIN CHAINPUR (200210) Male BC 04/04/1964 Urdu 01/06/1982 Elementary (1 TO 8) SHAHPUR, CHAINPUR, PALAMU KALAN RAMESH KUMAR UPG RAJKIYEKRIT HIGH SCHOOL BISHRAMPUR Unreserv UPPER PRIMARY (6 5 Male 06/05/1961 History 14/08/1982 Village ketat post ketat palamau Jharkhand CHOUBEY KETAT (200209) ed TO 8) RAJKIYEKRIT GIRLS MS HARIHARGANJ VILL-DIHARI, PO-MATPA, PS-AMBA, DIST- 6 KAVILAS PD MEHTA Male BC 09/12/1961 All Subject 14/08/1982 PRIMARY (1 TO 5) HARIHARGANJ (200202) AURANGABAD (BIHAR) , PIN-824111 RAJKIYEKRIT BOYS MS Hussainabad Unreserv UPPER PRIMARY (6 Vill- TIKARI PO - Kamgarpur PS -HUSSAINABAD 7 UDAI PRATAP SINGH Male 02/01/1963 Art Education 14/08/1982 HUSAINABAD (200204) ed TO 8) DIST - PALAMU JHARKHAND 82116 VILL - KOT KHAS PO - LESLIGANJ PS - LESLIGANJ 8 KRIPANARAYAN PRASAD RAJKIYEKRIT GIRLS MS NURU PANKI (200203) Male SC 10/01/1961 All Subject 16/08/1982 PRIMARY (1 TO 5) DIST - PALAMU PIN - 822118 SATBARWA 9 JALAL UDDIN ANSARI RAJKIYEKRIT URDU MS TABAR Male BC 10/03/1963 Other Subject 16/08/1982 PRIMARY (1 TO 5) Vill- Mukta Satbarwa Palamau Jharkhand (200213) UPG RAJKIYEKRIT HIGH SCHOOL DALTONGANJ Social Studies / UPPER PRIMARY (6 REDMA, WARD NO. -

An Anthropological Study of Rural Jharkhand, India

Understanding the State: An Anthropological Study of Rural Jharkhand, India Alpa Shah London School of Economics and Political Science University of London PhD. in Anthropology 2003 UMI Number: U615999 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615999 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 ?O ltT tC A L AND uj. TR£££ S F ZZit, Abstract This thesis explores understandings of the state in rural Jharkhand, Eastern India. It asks how and why certain groups exert their influence within the modem state in India, and why others do not. To do so the thesis addresses the interrelated issuesex-zamindar of and ex-tenant relations, development, corruption, democracy, tribal movements, seasonal casual labour migration, extreme left wing militant movements and moral attitudes towards drink and sex. This thesis is informed by twenty-one months of fieldwork in Ranchi District of which, for eighteen months, a village in Bero Block was the research base. The thesis argues that at the local level in Jharkhand there are at least two main groups of people who hold different, though related, understandings of the state. -

State of Kerala and Anr Vs Chandramohanan on 28 January, 2004 Supreme Court of India State of Kerala and Anr Vs Chandramohanan on 28 January, 2004 Bench: V.N

State Of Kerala And Anr vs Chandramohanan on 28 January, 2004 Supreme Court of India State Of Kerala And Anr vs Chandramohanan on 28 January, 2004 Bench: V.N. Khare Cj, S.B. Sinha, S.H. Kapadia CASE NO.: Appeal (crl.) 240 of 1997 PETITIONER: STATE OF KERALA AND ANR. RESPONDENT: CHANDRAMOHANAN DATE OF JUDGMENT: 28/01/2004 BENCH: V.N. KHARE CJ & S.B. SINHA & S.H. KAPADIA JUDGMENT: JUDGMENT 2004 (1)SCR 1155 The following Order of the Court was delivered One Ramachandran, who was the President of the Pattambi Congress Mandlam, lodged a complaint against the respondent alleging that on 24th October, 1992, the respondent at 3.30 p.m. took one eight year old girl named Elizabeth P. Kora to the class room in the Patambi Government U.P. School, with an intent to dishonour and outrage her modesty. On list November, 1992, the said complaint was treated as a First Information Report under Section 509 of the Indian Penal Code. Subsequently on 21st November, 1992, the Investigating officer came to know that the father of the victim belonged to the Mala Aryan Community, which is considered to be Scheduled Tribe in the State of Kerala and lodged another First Information Report, charging the respondent under Section 3(i)(xi) of the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrcoities) Act, 1989 (hereinafter referred to as 'the Act'). On the basis of the said First Information Reports, the Chief Judicial Magistrate summoned the respondent taking cognizance against him under Section 3(l)(xi) of the Act as well as under Section 509 of the Indian Penal Code. -

Tribal Communities of India: a Case Study of Oraon Community Dr

The Researchers’ - Volume II, Issue I, July-2016 ISSN : 2455-1503 International Journal of Research Tribal communities of India: A case study of Oraon community Dr. Rekha Maitra , Assistant Professor-Hospitality, Faculty of Management Studies, Manav Rachna International University, New Delhi. Abstract: India is a democratic and sovereign country, where people of all religion live together. India is a land of religious harmony maintains the equilibrium of keeping all the communities in one place. As per the Constitution of the Indian Republic; there are total of 645 district tribes. The term "Scheduled Tribes" refers to specific indigenous peoples whose status is acknowledged to some formal degree by national legislation. i According to Cambridge Dictionary, “Tribe is a group of people, often of related families, who live together, sharing the same language, culture, and history, especially those who do not live in towns or cities. In a considerably developed and civilized country like India, Tribal community in India has not seen enough daylight as an accepted community”. (Press, 2016) The regime has established provisions for adequate representation of tribes in their servings. To facilitate their adequate representation certain concessions have been offered, such as: (i) Exemption in age limits, (ii) Relaxation in the standard of suitability (iii) Inclusion at least in the lower category for the purpose of promotion is otherwise than through qualifying examinations. This research paper concentrates on the social status and the tolerance of the Oraon tribe in India. A brief introduction of Oraon community is as follows: The Oraon tribes उरांव or Kurukh कड़खु ु tribe is tribal aborigines inhabiting various states across central and eastern India, Bangladesh and Bhutan. -

GK Digest: April 2017 Bankexamstoday.Com

GK Digest: April 2017 BankExamsToday.Com 3/31/2017 BankExamsTodayEditorial Ramandeep Singh GK Digest: April 2017 Table of Contents Current Affairs ....................................................................................................................................................................................... 1 Banking & Financial Awareness One-Liner: March 2017 ...................................................................................................... 114 Banking And Financial Awareness: March (1 to 5).................................................................................................................. 116 List of Mergers & Acquisitions (Jan - March 2017).................................................................................................................. 117 International Financial Organizations: Headquarters & Functions ................................................................................... 122 List Government Schemes, Web Portal and Apps Launched (January) ............................................................................. 124 List of MoUs Signed between India and other Nations (2016-17)...................................................................................... 128 List of Government Schemes, Mobile Apps & Web Portal: February 2017....................................................................... 131 List of Appointments - February to March 2017 ..................................................................................................................... -

Food Availability at Fuel Outlets Of

S No SAP ID Merchant ID SO DO State Name of Retail Outlet Location District Contact Number Contact Person NH/SH 1 203436 3212000077 BHSO Bihar BEGUSARAI Bihar ANANYA AUTOMOBILES DALSINGHSARAI NH-28 SAMASTIPUR 9386004132 MINU NH 2 250162 3213000098 BHSO Bihar RANCHI Jharkhand AVON FILLING STATION KHARIA COLONY NH33 EAST SINGHBHUM9234567880 NAVEEN KAPOOR NH 3 217661 3213000074 BHSO Bihar RANCHI Jharkhand DEEPIKA FUELS TONTOPOSI WEST SINGHBHUM7004834697 CHANDRA MOHAN NAGSH Not 4 168880 BHSO Bihar RANCHI Jharkhand GLDC DALTONGANJ DALTONGANJ PALAMU 9431138856 SUNIL JAIN Available 5 190869 3426000012 BHSO Bihar Dhanbad Jharkhand Hemkund Filling Point NH-2, Topchachi Dhanbad 7870587777, 9708407777 Tarun Singh NH 6 168889 3205000019 BHSO Bihar RANCHI Jharkhand HIGHWAY AUTOMOBILES BUNDU NH33 RANCHI 8084206615 KAMLESH KUMAR NH 7 168664 3210000006 BHSO Bihar Dhanbad Jharkhand Jain Highway Service Station NH-2, Bagodar Giridih 7004040010, 9955301996 Rajesh Jain NH Not 8 318390 3210000021 BHSO Bihar Dhanbad Jharkhand Jublee Retail Outlet Jasidih Deoghar 9628650444 Ritesh Kumar Available 9 169212 3213000044 BHSO Bihar RANCHI Jharkhand KARTIK ORAON ASANBANI NH33 SARAIKELA KHARSAWAN8797563809 SOMA ORAON NH 10 190854 3210000046 BHSO Bihar Dhanbad Jharkhand Kumar Service Station Bokaro City Bokaro 9430135515 Amardeep Kumar NH 11 198166 3213000046 BHSO Bihar Dhanbad Jharkhand Laxmi Fuel and Service Maharo Dumka 7992291498 Milan Kumar SH 12 269539 3213556018 BHSO Bihar RANCHI Jharkhand MADHURI FUELS RAGAMATI NH33 SARAIKELA KHARSAWAN9939354651 PRAVEEN KUMAR -

Online & Offline Total Website List.Xlsx

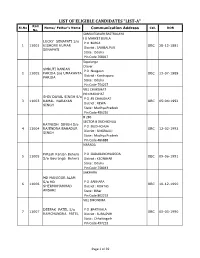

LIST OF ELIGIBLE CANDIDATES "LIST-A" Roll Sl.No Name/ Father's Name Communication Address Cat. DOB No. SAMALESWARI BASTRALAYA I G MARKET BURLA LUCKY SENAPATI S/o P O :BURLA 1 11001 KISHORE KUMAR OBC 28-12-1991 District : SAMBALPUR SENAPATI State : Odisha Pin Code 768017 Sapalanga Olaver SMRUTI RANJAN P O :Nuagaon 2 11002 PARIDA S/o UMAKANTA OBC 13-07-1989 District : Kendrapara PARIDA State : Odisha Pin Code 754227 VILL CHAKGHAT PO CHAKGHAT SHIV DAYAL SINGH S/o P O :PS CHAKGHAT 3 11003 KAMAL NARAYAN OBC 05-04-1992 District : REWA SINGH State : Madhya Pradesh Pin Code 486226 B 286 SECTOR B DUDHICHUA RATNESH SINGH S/o P O :DUDHICHUA 4 11004 RAJENDRA BAHADUR OBC 12-02-1993 District : SINGRAULI SINGH State : Madhya Pradesh Pin Code 486888 NARADA Pritesh Ranjan Behera P O :GADABANDHAGODA 5 11005 OBC 09-06-1991 S/o Gouranga Behera District : KEONJHAR State : Odisha Pin Code 758043 SAKHARA MD MANJOOR ALAM S/o MD P O :SAKHARA 6 11006 OBC 10-12-1990 SHERMOHAMMAD District : ROHTAS ANSARI State : Bihar Pin Code 802219 VILL DHONDHA DEEPAK PATEL S/o P O :BARTIKALA 7 11007 OBC 05-03-1990 RAMCHANDRA PATEL District : SURAJPUR State : Chhattisgarh Pin Code 497223 Page 1 of 39 TOPA COLLIERY LCH-170 ANIL KUMAR GUPTA P O :TOPA COLLIERY 8 11008 OBC 04-10-1986 S/o KRISHNA SAO District : RAMGARH State : Jharkhand Pin Code 825330 VILL- UKHARBERWA SUGIA KAILASH MAHTO S/o P O :KARMA 9 11009 OBC 14-12-1988 SITAL MAHTO District : RAMGARH State : Jharkhand Pin Code 829117 THOUBAL WANGMATABA WAIKHOM THAKUR P O :THOUBAL 10 11010 SINGH S/o W JILLA OBC 02-03-1991 District -

New Roles for Indigenous Women in an Indian Eco-Religious Movement

religions Article New Roles for Indigenous Women in an Indian Eco-Religious Movement Radhika Borde Department of Social Geography and Regional Development, Charles University, Prague 128 00, Czech Republic; [email protected] Received: 12 August 2019; Accepted: 22 September 2019; Published: 26 September 2019 Abstract: This article aims to study how a movement aimed at the assertion of indigenous religiosity in India has resulted in the empowerment of the women who participate in it. As part of the movement, devotees of the indigenous Earth Goddess, who are mostly indigenous women, experience possession trances in sacred natural sites which they have started visiting regularly. The movement aims to assert indigenous religiosity in India and to emphasize how it is different from Hinduism—as a result the ecological articulations of indigenous religiosity have intensified. The movement has a strong political character and it explicitly demands that indigenous Indian religiosity should be officially recognized by the inclusion of a new category for it in the Indian census. By way of their participation in this movement, indigenous Indian women are becoming figures of religious authority, overturning cultural taboos pertaining to their societal and religious roles, and are also becoming empowered to initiate ecological conservation and restoration efforts. Keywords: India; sacred natural sites; indigenous; women; new religious movements; mobilizations 1. Introduction This article examines a new religious movement with strong ecological articulations that is gaining ground among the indigenous or Adivasi1 people of east-central India. The movement accords a uniquely pivotal role to women—as legitimately channeling the Earth Goddess via possession trances. -

HIGH COURT of JHARKHAND, RANCHI INDEX (Daily Cause List

HIGH COURT OF JHARKHAND, RANCHI INDEX (Daily Cause List dated 28.06.2021) Sl. TIME BENCHES No. PAGE NO. 1 NOTICES 1-10 2 10:30 A.M. Hon’ble The Chief Justice 11-12 & Hon’ble Mr. Justice Sujit Narayan Prasad 3 10:30 A.M. Hon’ble Mr. Justice Aparesh Kumar Singh 13-14 & Hon’ble Mrs. Justice Anubha Rawat Choudhary 4 10:30 A.M. Hon’ble Mr. Justice S.Chandrashekhar 15-16 & Hon’ble Mr. Justice Ratnaker Bhengra 5 10:30 A.M. Hon’ble Mr. Justice Rongon Mukhopadhyay 17-38 6 11:00 A.M Hon’ble Mr. Justice Ananda Sen 39-43 7 10:30 A.M. Hon’ble Mr. Justice Dr. S.N.Pathak 44-46 8 10:30 A.M. Hon’ble Mr. Justice Rajesh Shankar 47-48 9 10:30 A.M. Hon’ble Mr. Justice Anil Kumar Choudhary 49-55 10 10:30 A.M. Hon’ble Mr. Justice Rajesh Kumar 56-58 11 After the DB Hon’ble Mrs. Justice Anubha Rawat Choudhary 59-60 12 10:30 A.M. Hon’ble Mr. Justice Kailash Prasad Deo 61-62 13 10:30 A.M. Hon’ble Mr. Justice Sanjay Kumar Dwivedi 63-64 14 10:30 A.M. Hon’ble Mr. Justice Deepak Roshan 65-66 15 11:30 A.M Registrar General 67-69 16 11:30 A.M Joint Registrar Judicial 70-71 National Lok Adalat “National Lok Adalat” is proposed to be held on Saturday, the 10th day of July, 2021, under the aegis of National Legal Services Committee, in association with High Court Legal Services Committee, Ranchi. -

The Dichotomy of Sexual and Artistic Productions In

VICTORIAN JOURNAL OF ARTS Vol. X, Issue II July 2017 VICTORIAN JOURNAL OF ARTS ISSN: 0975 – 5632 Vol. X, Issue II July 2017 UGC Enlisted Journal No.41277 BOARD OF ADVISORS Ratanlal Chakraborty, Former Professor, Dept. of History, University of Dhaka Nrisingha Prasad Bhaduri, Eminent Professor of Sanskrit and Writer Ananda Gopal Ghosh, Former Professor, Dept. of History, University of North Bengal Bimal Kumar Saha, Officer-in-Charge, A.B.N. Seal College, Cooch Behar EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Debabrata Lahiri, Associate Professor, Dept. of Economics, A.B.N. Seal College, Cooch Behar EDITORIAL BOARD Mithu Sinha Ray, Assistant Professor, Dept. of Philosophy, A.B.N. Seal College, Cooch Behar Writuparna Chakraborty, Assistant Professor, Dept. of Geography, A.B.N. Seal College, Cooch Behar Ratul Ghosh, Assistant Professor, Dept. of Bengali, A.B.N. Seal College, Cooch Behar Dibyatanu Dasgupta, Assistant Professor, Dept. of Bengali, A.B.N. Seal College, Cooch Behar Debapratim Chakraborty, Assistant Professor, Dept. of English, A.B.N. Seal College, Cooch Behar Sudeshna Mukherjee, Assistant Professor, Dept. of English, A.B.N. Seal College, Cooch Behar Durbadal Mandal, Assistant Professor, Dept. of Sanskrit, A.B.N. Seal College, Cooch Behar Bishnupriya Saha, Assistant Professor, Dept. of Philosophy, A.B.N. Seal College, Cooch Behar PUBLISHER: Office of the Principal, A. B. N. Seal College, Cooch Behar FOREWORD It is not only a matter of pleasure but also of great relief that we are able to present to the readers the July 2017 issue of Victorian Journal of Arts, just in time to coincide with the occasion of the Annual Day and Founders’ Day of the College, which is customarily the case every year. -

Lok Sabha Debates

Tuesday, April 15, 1969 Fourth Series1R.40 Chaitra 25, 1891 (Saka) /2.6$%+$ '(%$7(6 Seventh Session Fourth/RN6DEKD /2.6$%+$6(&5(7$5,$7 New Delhi CONTENTS Nos. 40-TuesMY, April1S, 1969/Chaitra 25, 1891 (SAKA) Columns Oral Answers to Questions- *Starred Question Nos. \081 to 1085 1-29 Written Answers to Questrons - Starred Questions Nos. 1086 to 11 lit 29-50 Unstarred Qaestions Nos. 6365 to 6374.6376 to 6414, 6416. 6417.6419 to 6472, 6474 to 6486,6488 to 6490, 6492 to 6496, 6498 to 6504 and 6506 to 6540 ... 50-181 Re. Proccdur~ in the House 181-34 Papers Laid on the Table 184-85 Estimates Committee- Statement reo Replies to Recommendations 185 Public Accounts Committec- ' Forty-fifth Report 185 Committee on Public Undeltakings- Thirty·first Report 185 Motion reo su.,pension of.Rule 338 in respect of Constitution (Twenty-second Amendment) Bill 185 Shri Shri Chand Goyal ... 186-87 Shri Abdul Ghani Dar ••• 187-91 Constitution (Twenty-second Amendment) Bill 191-277 Motion to consider 191·233 Shri Y.B. Chavan 191-99 Shri Abdul Ghani Dar I 99-20! Shri Ranga 204·06 Shri H.N. Mukerjec 206-Q9 Shri Shri Chand Goyal .•• 209-12 Shri Krishna Kumar Chatterji 212-14 Shri Swell 215·17 Shri Nambiar 217-19 Shri Jaipal Singh 219·21 Shri S,M. Joshi 221·23 Shri Surendranath Dwivedy 223·25 Shri Kartik Oraon 225·27 Shri Prakash Vir Shastri ... 227-31 Shri B.K. Daschowdhury 231·33 Clauses 2 to 4 and 1 233·69 Motion to pass 262 Shri Y.B. -

S.No. District Code Name of the Establishment Address Major

Jharkhand S.No. District Name of the Address Major Activity Broad NIC Owners Employ Code Establishment Description Activity hip ment Code Code Class Interval 1 01 Madhya vidhalya sisari 822114 Education 20 851 1 15-19 BOKARO STEEL 2 BHAVNATHPUR Mining 05 051 4 25-29 MINES TOWNSHEEP BHAVNATHPUR TOWNSHEEP 822112 201 VATIKA HOTEL 9 GURUDAWARA Resturant 14 561 2 15-19 GALI GURUDAWARA GALI 815301 304 SAWAN BEAR BAR 19 GANDHI CHOWK Resturant 14 563 2 10-14 GANDHI CHOWK 404 815301 MAHATO HOTEL 103 AURA AURA Hotel 14 562 2 10-14 504 825322 6 04 HOTEL KALPANA 19 ISRI ISRI 825107 Resturant 14 561 2 15-19 7 04 HOTEL KAVERI 64 ISRI ISRI 825107 Resturant 14 561 2 10-14 HARIDEVI REFRAL 89 THAKURGANGTI Health 21 861 1 10-14 806HOSPITAL 813208 RAJMAHAL 105 814154 Health 21 861 4 30-99 PARIYOJNA 906HOSPITAL SAMUDAYIK HEALTH PATHERGAMA 814147 Health 21 861 1 30-99 10 06 CENTER SAMUDYIK HEALTH 129 SUNDERPAHARI Health 21 861 1 15-19 CENTER 814133 11 06 rajkiya madh vidyalaya 835302 Education 20 851 1 15-19 12 11 jeema ICICI BANK 160 RAMGARH Banking 16 641 2 10-14 13 16 829118 PRATHMIK BLOCK MOD Health 21 861 1 15-19 SWASTHYA KENDRA PATRATU 829118 14 16 CCL HOSPITAL 82 RAMGARH 829106 Health 21 871 1 30-99 15 16 BHURKUNDA JINDAL STEEL AND 4(1) PATRATU Manufature 06 243 4 >=500 16 16 POWER BALKUDRA 829118 KEDLA WASHRI BASANT PUR Mining 05 051 2 >=500 17 16 WASHRI 829101 PRERNA MAHILA 126(2) SANGH Retail 12 472 5 10-14 VIKASH MANDAL RAMNAGAR BARKA CHUMBA 18 16 RAMNAGAR 829101 BIRU TASHA PARTY 89(2) BARKA Exitment 19 772 2 15-19 CHUMBA BRAHMAN 19 16 MUHALLA 829101