Classification and Misclassification of Childhood Apraxia of Speech

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phonological Processing Deficits As a Universal Model for Dyslexia

DOI: 10.1590/2317-1782/20142014135 Systematic Review Phonological processing deficits as a universal model Revisão Sistemática for dyslexia: evidence from different orthographies Ana Luiza Gomes Pinto Navas1 Déficit em processamento fonológico como um modelo universal Érica de Cássia Ferraz2 Juliana Postigo Amorina Borges2 para a dislexia: evidência a partir de diferentes ortografias Keywords ABSTRACT Dyslexia Purpose: To verify the universal nature of the phonological processing deficit hypothesis for dyslexia, since Education the most influential studies on the topic were conducted in children or adults speakers of English. Research Language strategy: A systematic review was designed, conducted and analyzed using PubMed, Science Direct, and Reading SciELO databases. Selection criteria: The literature search was conducted using the terms “phonological Review processing” AND “dyslexia” in publications of the last ten years (2004–2014). Data analysis: Following screening of (a) titles and abstracts and (b) full papers, 187 articles were identified as meeting the pre- established inclusion criteria. Results: The phonological processing deficit hypothesis was explored in studies involving several languages. More importantly, we identify studies in all types of writing systems such as ideographic, syllabic and logographic, as well as alphabetic orthography, with different levels of orthography- phonology consistency. Conclusion: The phonological processing hypothesis was considered as a valid explanation to dyslexia, in a wide variety of spoken languages and writing systems. Descritores RESUMO Dislexia Objetivo: Verificar a natureza universal da hipótese do déficit de processamento fonológico para a dislexia, uma Educação vez que os estudos mais influentes sobre o tema foram conduzidos com crianças ou adultos falantes do Inglês. Linguagem Estratégia de pesquisa: Uma revisão sistemática foi planejada, conduzida e analisada utilizando as bases de Leitura dados PubMed, Science Direct e SciELO. -

Speech/Language Impairment Sheet

West Virginia State Department of Education Office of Special Education * 1-800-558-2696 * http://wvde.state.wv.us/osp/ Fact Speech/Language Impairment Sheet DEFINITION Voice: Speech impairment where the child’s voice has an IDEA defines a speech or language impairment as a abnormal quality of pitch, resonance, or loudness. communication disorder, such as stuttering, impaired articulation, a language impairment, or a voice Persistent voice issues can indicate problems such as impairment that adversely affects a child’s educational vocal cord nodules, which should be addressed. Some performance. students who have structural abnormalities, such as cleft palate or palatal insufficiency, may exhibit a nasal SPEECH DISORDERS sound to their speech. An otolaryngologist must verify Speech Sound Disorders: Speech impairment where the the absence or existence of structural or functional child has difficulty producing sounds. Most children pathology before voice therapy can be provided. make some mistakes as they learn to say new words. A speech sound disorder occurs when mistakes continue Dysphagia: Some children may have difficulty eating past a certain age. Every sound has a different range of (chewing and swallowing food) and drinking without ages when the child should make the sound correctly. aspiration. The speech-language pathologist may be involved in developing a plan, along with other team Speech sound disorders include problems with members, to ensure that the child is provided with safe articulation (making sounds) and phonological nourishment and hydration during school hours. processes (patterns of sounds). COMMUNICATION DISORDERS Sounds can be substituted (saying “tat” for “cat”), left Augmentative and Alternative Communication: the use off (saying “ca” instead of “cat”), added (saying “kwat” of an alternative to speaking as a substitute for speech instead of “cat”) or changed (saying the sound or to supplement speech. -

Preventing Speech and Language Disorders ASHA

ASHA / Preventing Speech and Language Disorders ASHA / Keep your communication in top form • Tips for preventing – speech sound disorders – stuttering – voice disorders – language disorders ASHA / Speech sound disorders • Signs include – substituting one sound for another (wabbit for rabbit) – leaving sounds out of words (winnow for window) – changing how sounds are made, called distortions ASHA / Speech sound disorder prevention tips • Talk, read, and play with your child every day. – Children learn sounds and words by hearing and seeing them. • Take care of your child’s teeth and mouth. • Have your child’s hearing checked. • Have your child’s speech screened at a local clinic or school. ASHA / Stuttering • Many children may stutter sometimes. This is normal and should go away. • Signs of stuttering include – repeating sounds at the beginning of words (“b-b-bball”) – pausing while talking – stretching sounds out (“sssssssnake” for “snake”) – saying “um” or “uh” a lot while talking ASHA / Stuttering prevention tips • Give your child time to talk. • Try not to interrupt your child while he or she is speaking. • Have your child tested by a speech-language pathologist (SLP) if you are worried. ASHA / Voice disorders Signs include • hoarse, breathy, or nasal-sounding voice • speaking with a pitch that is too high or too low • talking too loudly or too softly • easily losing your voice ASHA / Voice disorders prevention tips • Try not to shout or scream, or to talk in noisy places. • Drink plenty of water. – Water keeps the mouth and throat moist. • Avoid alcohol, caffeine, chemical fumes (such as from cleaning products), and smoking. • See a doctor if you have allergies or sinus or respiratory infections. -

Developmental Verbal Dyspraxia

RCSLT POLICY STATEMENT DEVELOPMENTAL VERBAL DYSPRAXIA Produced by The Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists © 2011 The Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists 2 White Hart Yard London SE1 1NX 020 7378 1200 www.rcslt.org DEVELOPMENTAL VERBAL DYSPRAXIA RCSLT Policy statement Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................... 3 Introduction ............................................................................................................. 4 Process for consensus .............................................................................................5 Characteristics of Developmental Verbal Dyspraxia .....................................................5 Table 1: Characteristic Features of DVD ....................................................................7 Change over time ...................................................................................................8 Terminology issues ................................................................................................. 8 Table 2: Differences in preferred terminology ........................................................... 10 Aetiology ............................................................................................................. 10 Incidence and prevalence of DVD ........................................................................... 11 Co-morbidity ....................................................................................................... -

Specific Language Impairment (SLI) Versus Speech Sound Disorders

https://edition.pagesuite-professional.co.uk/html5/reader/production/default.aspx?pubname=&edid=558600cb-8de9-4616-9242-f8f3b41da315 This article originally appeared in the May 2018 PROFILE issue of Open Access Government Specific Language Impairment (SLI) versus Speech Sound Disorders (SSD) The important differences between Specific Language Impairment (SLI) in children and Speech Sound Disorders (SSD) in children are placed under the spotlight by Mabel L. Rice, Fred & Virginia Merrill Distinguished Professor of Advanced Studies at the University of Kansas round the world young chil- they are hearing. Their first job is to SSD can be obvious to adult listeners dren are expected to learn refine them to match the ones they of young children. Young children’s the language they overhear in need and to drop the ones that may attempts to talk can be unintelligible, Aconversations around them. This is a not matter and to develop the motor especially when they are very young. robust, spontaneous ability of humans, control needed to do that. If unintelligibility persists as children unlike, for example, reading, which age, it becomes noticeable and a must be explicitly taught. One promi- Humans at birth are equipped with matter of concern because it is nent scholar of children’s language motor movements for breathing, not “typical.” Some mispronunciations acquisition once put it this way: “… sucking and swallowing (basic func- are understandable but regarded as there is virtually no way to prevent it tions for survival), along with a wide immature, such as “wabbit” for “rabbit”, from happening short of raising a child range of sounds. -

Child Speech Sound Disorder: Special Edition 1 RCSLTRCSLT Impactimpact Rereportport 202014-201514-2015 Septemseptemberber 2015 |

Child speech sound disorder: special edition 1 RCSLTRCSLT ImpactImpact ReReportport 202014-201514-2015 SeptemberSeptember 2015 | www.rcswww.rcslt.orglt.org 001_Cover_Bulletin1_Cover_Bulletin ATEATE AugAug 2019_Bulletin2019_Bulletin 1 008/07/20198/07/2019 113:253:25 Wish there were two of you to do your job? U~fv|fq`|YuX~fvdWLXYaNqPdÂ~fv`df||XCuYuuC`PrufcC`PCqPCaNYPqPdLPYduXPYqaCdWvCWPfvuLfcPrà What if there was a way to multiply your impact and increase the support each child receives? <XYaP|PvdUfquvdCuPa~LCd·uLafdP~fvÊrfqq~ÂYu·rdfufvqrnPLYCau~ËÂ|XCu|PLCdNfYruXPdP}uKPruuXYdWÃ<P LCdfPq~fvuXPcfruPPLuY{PuffarUfqPdWCWYdWCdNPcnf|PqYdWnCqPdurufP}uPdN~fvqYcnCLuYdufuXP XfcPÒuXCuYrÂufcC`PYduPq{PduYfdCdCuvqCaÂfdWfYdWnqfLPrrUfqP{Pq~LXYaNà At a Hanen workshop, you’ll gain a world-renowned, evidence-based coaching framework that leads to lasting Ycnqf{PcPdurYdnCqPduÔLXYaNYduPqCLuYfdCdNLfccvdYLCuYfdÃ<YuXCruPnÔK~ÔruPnWvYNPCdNrYcnaPcCuPqYCar nCqPdur|Yaaaf{PÂ~fv·aarffdKPcC`YdWCKYWWPqNYPqPdLPuXCd~fvP{PqYcCWYdPNà Pick your population and register for a Hanen workshop today. Language Delay - It Takes Two to Talk® workshop London, England ................ Nov 27-29, 2019 Autism - More Than Words® workshop Edinburgh, Scotland ........ Sept 9-11, 2019 Autism - More Than Words® workshop London, England ............... Dec 16-18, 2019 2 Ask the Experts Learn more at www.hanen.org August 2019 | www.rcslt.org 002-03_Contents_Bulletin2-03_Contents_Bulletin ATEATE AugAug 2019_Bulletin2019_Bulletin 2 005/07/20195/07/2019 112:512:51 CONTENTS THE EXPERTS ASK Contents -

SLP Summit Farquharson 12.5.19

Kelly Farquharson, Ph.D., CCC-SLP Reading with TLC | 2.28.18 Why speech sounds matter for Kelly Farquharson, Ph.D., CCC-SLP [email protected] Disclosures • Financial: I am a faculty member at Florida and receive a salary for that job. • Nonfinancial: I am the director of the Children’s Literacy and Speech Sound (CLaSS) Lab Learning Objectives •Identify the role of phonological representations •Discuss the risk factors and outcomes for children with persistent or remediated speech sound disorders as well as those with dyslexia •Discuss the SLPs role in facilitating literacy skills for children with speech sound disorder and those with dyslexia 3 [email protected] www.facebook.com/classlabemerson Kelly Farquharson, Ph.D., CCC-SLP Reading with TLC | 2.28.18 Children’s Literacy and Speech Sound (CLaSS) lab •http://classlab.cci.fsu.edu •Instagram: @classlab_FSU •Twitter: @literacyspeech •www.facebook.com/literacyspeech Observation from a school-based SLP: Subgroups of SSD???? Remediates YES NO Motor Deficit? NO True Linguistic phonological Deficit? deficit YES Literacy Problems Literacy What is reading? [email protected] www.facebook.com/classlabemerson Kelly Farquharson, Ph.D., CCC-SLP Reading with TLC | 2.28.18 Who is reading? The Simple View of Reading (Catts, Hogan, & Fey, 2003; Catts, Hogan, & Adlof, 2005; Gough & Tunmer, 1986; Hoover & Gough, 1990) Reading The Simple View of Reading (Catts, Hogan, & Fey, 2003; Catts, Hogan, & Adlof, 2005; Gough & Tunmer, 1986; Hoover & Gough, 1990) Reading Word Recognition [email protected] www.facebook.com/classlabemerson -

Speech-Language Disorders & Therapy Explanation Handouts

Speech-Language Disorders & Therapy Explanation Handouts for Parents & Teachers By Natalie Snyders, MS, CCC-SLP Making the life of a busy school SLP easier and a bit SPEECH-LANGUAGE PATHOLOGIST more beautiful every day! W W W . S L P N A T A L I E S N Y D E R S . C O M Directions: These handouts are intended to be used by speech-language pathologists to provide information to parents, teachers, and other staff members about the role of speech-language therapy in the school setting, the evaluation & IEP process, what exactly various communication disorders are, and how those communication disorders may impact the academic environment. I highly recommend making multiple copies ahead of time, so you can quickly grab a set when you need them. They are all in black and white, so no need for colored ink! I like to print them on brightly colored paper to help them stand out. I also recommend making stapled packets of relevant pages together (for example, the overview of speech-language therapy, explanation of a phonological disorder, and impact of speech sound disorders pages). These handouts are perfect to hand out during initial or yearly IEP meetings, to teachers at the beginning of the school year to have as a reference and to leave in their substitute binders, and to parents at the start of the school year. Terms of Use: Please note that this download is intended for the use of one SLP/teacher/ Graphics: user only. Please direct others interested to the original product page on TpT; multiple user licenses are available at a 10% discount. -

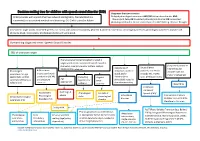

Decision Making Tree for Children with Speech Sound Disorder (SSD) Diagnoses That Can Co-Occur: Child Presents with Speech That Has Reduced Intelligibility

Decision making tree for children with speech sound disorder (SSD) Diagnoses that can co-occur: Child presents with speech that has reduced intelligibility. Parents/teachers Delayed phonological awareness AND/OR Articulation disorder AND Phonological delay OR Consistent phonological disorder OR Inconsistent concerned ; no associated medical conditions e.g. CP; Cleft Lip and/or Palate phonological disorder. In rare cases: Dysarthria AND CAS e.g. Worster Drought Assessment: single words; connected speech; oro-motor; articulation/stimulability; phonetic & phonemic inventory; phonological processes; phonological awareness (syllable and phoneme level); inconsistency (multiple productions of same word). Overarching diagnostic term: Speech Sound Disorder SSD of unknown origin Phonological errors/error patterns noted in single words and/or connected speech noted in phonemic inventory & error pattern analysis. (Suspected) motor or Distortions of Unusual error IPD/DVD/CAS ruled out neuromuscular 40% or more patterns, oro-motor, Phonological individual sounds in disorder with oro- inconsistent word words and in prosody etc., meets awareness not age motor involvement appropriate, and/or production (DEAP) Persisting Atypical isolation (non- strict DVD/CAS criteria Age continued difficulty at and DVD/CAS typical error error stimulable) noted in syllable level ruled out appropriate phonetic inventory patterns patterns Dysarthria Childhood Apraxia of Discharge & Inconsistent Phonological Consistent Speech (CAS)* advice Articulation Intervention choice is Delayed phonological Phonological delay phonological disorder complex. See up to date awareness (PA) Disorder (IPD) disorder literature in this area Delayed PA ReST (Rapid Syllable Transition (e.g. Ballard, Phonological Contrast intervention, Articulation 2001)); Integrated Phonological Awareness Phonological Core Review/ watchful in appropriate format to meet needs intervention, Intervention (e.g. -

Persistent Speech Sound Disorder at Age 8

Prevalence and predictors of persistent speech sound disorder at eight-years-old: Findings from a population cohort study Yvonne Wren PhD, Bristol Speech and Language Therapy Research Unit, North Bristol NHS Trust, Bristol, BS16 1LE, UK Tel: +44 117 3406529 Fax: +44 117 9701119 Email: [email protected] Laura L. Miller MSc, School of Social and Community Medicine, University of Bristol, Oakfield House, Oakfield Grove, Bristol, BS8 2BN ([email protected]) Tim J Peters PhD, School of Clinical Sciences, University of Bristol, 69 St Michael’s Hill, Bristol BS2 8DZ ([email protected]) Alan Emond MD, Centre for Child and Adolescent Health, School of Social and Community Medicine, University of Bristol, Oakfield House, Oakfield Grove, Clifton, Bristol, BS8 2BN ([email protected]) Sue Roulstone PhD, Faculty of Health and Life Sciences University of the West of England, Bristol. ([email protected]) 1 Abstract Purpose: To determine prevalence and predictors of persistent speech sound disorder (SSD) in children aged 8. Method: Data from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC) were used. Children were classified as having persistent SSD based on Percentage of Consonants Correct measures from connected speech samples. Multivariable logistic regression analyses were performed to identify predictors. Results: The estimated prevalence of persistent SSD was 3.6%. Children with persistent SSD were more likely to be male and from families who were not home-owners. Early childhood predictors identified as important were: weak sucking at 4 weeks; not often combining words at 24 months; limited use of word morphology at 38 months; and being unintelligible to strangers at age 38 months. -

Speech Sound Disorders

Speech Sound Disorders Table of Contents Introduction: Speech Sound Disorders…………………………………………………………………………………2 Articulation Disorders………………………………………………………………………………………………….………3 Phonological Disorders……………………………………………………………………………………………………..…3 Accented Speech………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….4 Treatment of Speech Sound Disorders…………………………………………………………………………………4 I. Speech Referral Guidelines……………………………………………………………………………….…5 I.a. Common Etiologies……………………………………………………………….………………….5 I.b. Potential Consequences and Impact of Speech Impairment……………………..5 I.c. Major Milestones for Speech Development………………………………………………6 I.d. Behaviors that Should Trigger an SLP Referral………………………………………….6 I.e. World Health Organization Model (WHO) International…………………………..7 II. Screening…………………………………………………………………………………………………………….9 II.a. ASHA Practice Policy……………………………………………………………………………….9 II.b. Screening Tools for Speech Sound Disorders……………………………………….…12 III. Assessment………………………………………………………………………………………………………..13 III.a. ASHA Practice Policy………………………………………………………………………………13 III.b. Published Tests for Assessment of Speech Sound Disorders………………….17 III.b.1 English Speech Sound Assessment Tools………………………….………17 III.b.2 Spanish Speech Assessment Tools……………………………………………23 III.b.3 Bilingual Speech Sound Assessment Tools……………………………….24 III.b.4 Assessment of Intelligibility……………………………………………………..25 IV. Differential Diagnosis…………………………………………………………………………………………26 IV.a. Phonological Disorders……………………….………………………………………………..27 IV.b. Dysarthria…………………………………….………………………………………………………28 -

Subtyping Children with Speech Sound Disorders by Endophenotypes

Top Lang Disorders Vol. 31, No. 2, pp. 112–127 Copyright c 2011 Wolters Kluwer Health | Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Subtyping Children With Speech Sound Disorders by Endophenotypes Barbara A. Lewis, Allison A. Avrich, Lisa A. Freebairn, H. Gerry Taylor, Sudha K. Iyengar, and Catherine M. Stein Purpose: The present study examined associations of 5 endophenotypes (i.e., measurable skills that are closely associated with speech sound disorders and are useful in detecting genetic in- fluences on speech sound production), oral motor skills, phonological memory, phonological awareness, vocabulary, and speeded naming, with 3 clinical criteria for classifying speech sound disorders: severity of speech sound disorders, our previously reported clinical subtypes (speech sound disorders alone, speech sound disorders with language impairment, and childhood apraxia of speech), and the comorbid condition of reading disorders. Participants and Method: Chil- dren with speech sound disorders and their siblings were assessed at early childhood (ages 4– 7 years) on measures of the 5 endophenotypes. Severity of speech sound disorders was deter- mined using the z score for Percent Consonants Correct—Revised (developed by Shriberg, Austin, Lewis, McSweeny, & Wilson, 1997). Analyses of variance were employed to determine how these endophenotypes differed among the clinical subtypes of speech sound disorders. Results and Conclusions: Phonological memory was related to all 3 clinical classifications of speech sound disorders. Our previous subtypes of speech sound disorders and comorbid conditions of language impairment and reading disorder were associated with phonological awareness, while severity of speech sound disorders was weakly associated with this endophenotype. Vocabulary was as- sociated with mild versus moderate speech sound disorders, as well as comorbid conditions of language impairment and reading disorder.