Dotazovací Jazyky

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Database Concepts 7Th Edition

Database Concepts 7th Edition David M. Kroenke • David J. Auer Online Appendix E SQL Views, SQL/PSM and Importing Data Database Concepts SQL Views, SQL/PSM and Importing Data Appendix E All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Printed in the United States of America. Appendix E — 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 E-2 Database Concepts SQL Views, SQL/PSM and Importing Data Appendix E Appendix Objectives • To understand the reasons for using SQL views • To use SQL statements to create and query SQL views • To understand SQL/Persistent Stored Modules (SQL/PSM) • To create and use SQL user-defined functions • To import Microsoft Excel worksheet data into a database What is the Purpose of this Appendix? In Chapter 3, we discussed SQL in depth. We discussed two basic categories of SQL statements: data definition language (DDL) statements, which are used for creating tables, relationships, and other structures, and data manipulation language (DML) statements, which are used for querying and modifying data. In this appendix, which should be studied immediately after Chapter 3, we: • Describe and illustrate SQL views, which extend the DML capabilities of SQL. • Describe and illustrate SQL Persistent Stored Modules (SQL/PSM), and create user-defined functions. • Describe and use DBMS data import techniques to import Microsoft Excel worksheet data into a database. E-3 Database Concepts SQL Views, SQL/PSM and Importing Data Appendix E Creating SQL Views An SQL view is a virtual table that is constructed from other tables or views. -

Scalable Computation of Acyclic Joins

Scalable Computation of Acyclic Joins (Extended Abstract) Anna Pagh Rasmus Pagh [email protected] [email protected] IT University of Copenhagen Rued Langgaards Vej 7, 2300 København S Denmark ABSTRACT 1. INTRODUCTION The join operation of relational algebra is a cornerstone of The relational model and relational algebra, due to Edgar relational database systems. Computing the join of several F. Codd [3] underlies the majority of today’s database man- relations is NP-hard in general, whereas special (and typi- agement systems. Essential to the ability to express queries cal) cases are tractable. This paper considers joins having in relational algebra is the natural join operation, and its an acyclic join graph, for which current methods initially variants. In a typical relational algebra expression there will apply a full reducer to efficiently eliminate tuples that will be a number of joins. Determining how to compute these not contribute to the result of the join. From a worst-case joins in a database management system is at the heart of perspective, previous algorithms for computing an acyclic query optimization, a long-standing and active field of de- join of k fully reduced relations, occupying a total of n ≥ k velopment in academic and industrial database research. A blocks on disk, use Ω((n + z)k) I/Os, where z is the size of very challenging case, and the topic of most database re- the join result in blocks. search, is when data is so large that it needs to reside on In this paper we show how to compute the join in a time secondary memory. -

“A Relational Model of Data for Large Shared Data Banks”

“A RELATIONAL MODEL OF DATA FOR LARGE SHARED DATA BANKS” Through the internet, I find more information about Edgar F. Codd. He is a mathematician and computer scientist who laid the theoretical foundation for relational databases--the standard method by which information is organized in and retrieved from computers. In 1981, he received the A. M. Turing Award, the highest honor in the computer science field for his fundamental and continuing contributions to the theory and practice of database management systems. This paper is concerned with the application of elementary relation theory to systems which provide shared access to large banks of formatted data. It is divided into two sections. In section 1, a relational model of data is proposed as a basis for protecting users of formatted data systems from the potentially disruptive changes in data representation caused by growth in the data bank and changes in traffic. A normal form for the time-varying collection of relationships is introduced. In Section 2, certain operations on relations are discussed and applied to the problems of redundancy and consistency in the user's model. Relational model provides a means of describing data with its natural structure only--that is, without superimposing any additional structure for machine representation purposes. Accordingly, it provides a basis for a high level data language which will yield maximal independence between programs on the one hand and machine representation and organization of data on the other. A further advantage of the relational view is that it forms a sound basis for treating derivability, redundancy, and consistency of relations. -

Join , Sub Queries and Set Operators Obtaining Data from Multiple Tables

Join , Sub queries and set operators Obtaining Data from Multiple Tables EMPLOYEES DEPARTMENTS … … Cartesian Products – A Cartesian product is formed when: • A join condition is omitted • A join condition is invalid • All rows in the first table are joined to all rows in the second table – To avoid a Cartesian product, always include a valid join condition in a WHERE clause. Generating a Cartesian Product EMPLOYEES (20 rows) DEPARTMENTS (8 rows) … Cartesian product: 20 x 8 = 160 rows … Types of Oracle-Proprietary Joins – Equijoin – Nonequijoin – Outer join – Self-join Joining Tables Using Oracle Syntax • Use a join to query data from more than one table: SELECT table1.column, table2.column FROM table1, table2 WHERE table1.column1 = table2.column2; – Write the join condition in the WHERE clause. – Prefix the column name with the table name when the same column name appears in more than one table. Qualifying Ambiguous Column Names – Use table prefixes to qualify column names that are in multiple tables. – Use table prefixes to improve performance. – Instead of full table name prefixes, use table aliases. – Table aliases give a table a shorter name. • Keeps SQL code smaller, uses less memory – Use column aliases to distinguish columns that have identical names, but reside in different tables. Equijoins EMPLOYEES DEPARTMENTS Primary key … Foreign key Retrieving Records with Equijoins SELECT e.employee_id, e.last_name, e.department_id, d.department_id, d.location_id FROM employees e, departments d WHERE e.department_id = d.department_id; … Retrieving Records with Equijoins: Example SELECT d.department_id, d.department_name, d.location_id, l.city FROM departments d, locations l WHERE d.location_id = l.location_id; Additional Search Conditions Using the AND Operator SELECT d.department_id, d.department_name, l.city FROM departments d, locations l WHERE d.location_id = l.location_id AND d.department_id IN (20, 50); Joining More than Two Tables EMPLOYEES DEPARTMENTS LOCATIONS … • To join n tables together, you need a minimum of n–1 • join conditions. -

SQL: Programming Introduction to Databases Compsci 316 Fall 2019 2 Announcements (Mon., Sep

SQL: Programming Introduction to Databases CompSci 316 Fall 2019 2 Announcements (Mon., Sep. 30) • Please fill out the RATest survey (1 free pt on midterm) • Gradiance SQL Recursion exercise assigned • Homework 2 + Gradiance SQL Constraints due tonight! • Wednesday • Midterm in class • Open-book, open-notes • Same format as sample midterm (posted in Sakai) • Gradiance SQL Triggers/Views due • After fall break • Project milestone 1 due; remember members.txt • Gradiance SQL Recursion due 3 Motivation • Pros and cons of SQL • Very high-level, possible to optimize • Not intended for general-purpose computation • Solutions • Augment SQL with constructs from general-purpose programming languages • E.g.: SQL/PSM • Use SQL together with general-purpose programming languages: many possibilities • Through an API, e.g., Python psycopg2 • Embedded SQL, e.g., in C • Automatic obJect-relational mapping, e.g.: Python SQLAlchemy • Extending programming languages with SQL-like constructs, e.g.: LINQ 4 An “impedance mismatch” • SQL operates on a set of records at a time • Typical low-level general-purpose programming languages operate on one record at a time • Less of an issue for functional programming languages FSolution: cursor • Open (a result table): position the cursor before the first row • Get next: move the cursor to the next row and return that row; raise a flag if there is no such row • Close: clean up and release DBMS resources FFound in virtually every database language/API • With slightly different syntaxes FSome support more positioning and movement options, modification at the current position, etc. 5 Augmenting SQL: SQL/PSM • PSM = Persistent Stored Modules • CREATE PROCEDURE proc_name(param_decls) local_decls proc_body; • CREATE FUNCTION func_name(param_decls) RETURNS return_type local_decls func_body; • CALL proc_name(params); • Inside procedure body: SET variable = CALL func_name(params); 6 SQL/PSM example CREATE FUNCTION SetMaxPop(IN newMaxPop FLOAT) RETURNS INT -- Enforce newMaxPop; return # rows modified. -

LATERAL LATERAL Before SQL:1999

Still using Windows 3.1? So why stick with SQL-92? @ModernSQL - https://modern-sql.com/ @MarkusWinand SQL:1999 LATERAL LATERAL Before SQL:1999 Select-list sub-queries must be scalar[0]: (an atomic quantity that can hold only one value at a time[1]) SELECT … , (SELECT column_1 FROM t1 WHERE t1.x = t2.y ) AS c FROM t2 … [0] Neglecting row values and other workarounds here; [1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scalar LATERAL Before SQL:1999 Select-list sub-queries must be scalar[0]: (an atomic quantity that can hold only one value at a time[1]) SELECT … , (SELECT column_1 , column_2 FROM t1 ✗ WHERE t1.x = t2.y ) AS c More than FROM t2 one column? … ⇒Syntax error [0] Neglecting row values and other workarounds here; [1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scalar LATERAL Before SQL:1999 Select-list sub-queries must be scalar[0]: (an atomic quantity that can hold only one value at a time[1]) SELECT … More than , (SELECT column_1 , column_2 one row? ⇒Runtime error! FROM t1 ✗ WHERE t1.x = t2.y } ) AS c More than FROM t2 one column? … ⇒Syntax error [0] Neglecting row values and other workarounds here; [1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scalar LATERAL Since SQL:1999 Lateral derived queries can see table names defined before: SELECT * FROM t1 CROSS JOIN LATERAL (SELECT * FROM t2 WHERE t2.x = t1.x ) derived_table ON (true) LATERAL Since SQL:1999 Lateral derived queries can see table names defined before: SELECT * FROM t1 Valid due to CROSS JOIN LATERAL (SELECT * LATERAL FROM t2 keyword WHERE t2.x = t1.x ) derived_table ON (true) LATERAL Since SQL:1999 Lateral -

Efficient Processing of Window Functions in Analytical SQL Queries

Efficient Processing of Window Functions in Analytical SQL Queries Viktor Leis Kan Kundhikanjana Technische Universitat¨ Munchen¨ Technische Universitat¨ Munchen¨ [email protected] [email protected] Alfons Kemper Thomas Neumann Technische Universitat¨ Munchen¨ Technische Universitat¨ Munchen¨ [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT select location, time, value, abs(value- (avg(value) over w))/(stddev(value) over w) Window functions, also known as analytic OLAP functions, have from measurement been part of the SQL standard for more than a decade and are now a window w as ( widely-used feature. Window functions allow to elegantly express partition by location many useful query types including time series analysis, ranking, order by time percentiles, moving averages, and cumulative sums. Formulating range between 5 preceding and 5 following) such queries in plain SQL-92 is usually both cumbersome and in- efficient. The query normalizes each measurement by subtracting the aver- Despite being supported by all major database systems, there age and dividing by the standard deviation. Both aggregates are have been few publications that describe how to implement an effi- computed over a window of 5 time units around the time of the cient relational window operator. This work aims at filling this gap measurement and at the same location. Without window functions, by presenting an efficient and general algorithm for the window it is possible to state the query as follows: operator. Our algorithm is optimized for high-performance main- memory database systems and has excellent performance on mod- select location, time, value, abs(value- ern multi-core CPUs. We show how to fully parallelize all phases (select avg(value) of the operator in order to effectively scale for arbitrary input dis- from measurement m2 tributions. -

SQL Procedures, Triggers, and Functions on IBM DB2 for I

Front cover SQL Procedures, Triggers, and Functions on IBM DB2 for i Jim Bainbridge Hernando Bedoya Rob Bestgen Mike Cain Dan Cruikshank Jim Denton Doug Mack Tom Mckinley Simona Pacchiarini Redbooks International Technical Support Organization SQL Procedures, Triggers, and Functions on IBM DB2 for i April 2016 SG24-8326-00 Note: Before using this information and the product it supports, read the information in “Notices” on page ix. First Edition (April 2016) This edition applies to Version 7, Release 2, of IBM i (product number 5770-SS1). © Copyright International Business Machines Corporation 2016. All rights reserved. Note to U.S. Government Users Restricted Rights -- Use, duplication or disclosure restricted by GSA ADP Schedule Contract with IBM Corp. Contents Notices . ix Trademarks . .x IBM Redbooks promotions . xi Preface . xiii Authors. xiii Now you can become a published author, too! . xvi Comments welcome. xvi Stay connected to IBM Redbooks . xvi Chapter 1. Introduction to data-centric programming. 1 1.1 Data-centric programming. 2 1.2 Database engineering . 2 Chapter 2. Introduction to SQL Persistent Stored Module . 5 2.1 Introduction . 6 2.2 System requirements and planning. 6 2.3 Structure of an SQL PSM program . 7 2.4 SQL control statements. 8 2.4.1 Assignment statement . 8 2.4.2 Conditional control . 11 2.4.3 Iterative control . 15 2.4.4 Calling procedures . 18 2.4.5 Compound SQL statement . 19 2.5 Dynamic SQL in PSM . 22 2.5.1 DECLARE CURSOR, PREPARE, and OPEN . 23 2.5.2 PREPARE then EXECUTE. 26 2.5.3 EXECUTE IMMEDIATE statement . -

1.204 Lecture 3, Database: SQL Joins, Views, Subqueries

1.204 Lecture 3 SQL: Basics, Joins SQL • Structured query language (SQL) used for – Data definition (DDL): tables and views (virtual tables). These are the basic operati ons t o convert a dat d ta model d l t o a database – Data manipulation (DML): user or program can INSERT, DELETE, UPDATE or retrieve (SELECT) data. – Data integrity: referential integrity and transactions. Enforces keys. – Access control: security – Data sharing: by concurrent users • Not a complete language like Java – SQL is sub-language of about 30 statements • Nonprocedural language – No branching or iteration – Declare the desired result, and SQL provides it 1 SQL SELECT • SELECT constructed of clauses to get columns and rows from one or more tables or views. Clauses must be in order: – SELECT columns/attributes – INTO new table – FROM table or view – WHERE specific rows or a join is created – GROUP BY grouping conditions (columns) – HAVING group-property (specific rows) – ORDER BY ordering criterion ASC | DESC Example tables OrderNbr Cust Prod Qty Amt Disc Orders 1 211 Bulldozer 7 $31,000.00 0.2 2 522 Riveter 2 $4,000.00 0.3 3 522 Crane 1 $500,000.00 0.4 CustNbr Company CustRep CreditLimit 211 Connor Co 89 $50,000.00 Customers 522 AmaratungaEnterprise 89 $40,000.00 890 Feni Fabricators 53 $1,000,000.00 RepNbr Name RepOffice Quota Sales SalesRepsp 53 Bill Smith 1 $100, 000. 00 $0. 00 89 Jen Jones 2 $50,000.00 $130,000.00 Offices OfficeNbr City State Region Target Sales Phone 1 Denver CO West $3,000,000.00 $130,000.00 970.586.3341 2 New York NY East $200,000.00 $300,000.00 -

Relational Databases, Logic, and Complexity

Relational Databases, Logic, and Complexity Phokion G. Kolaitis University of California, Santa Cruz & IBM Research-Almaden [email protected] 2009 GII Doctoral School on Advances in Databases 1 What this course is about Goals: Cover a coherent body of basic material in the foundations of relational databases Prepare students for further study and research in relational database systems Overview of Topics: Database query languages: expressive power and complexity Relational Algebra and Relational Calculus Conjunctive queries and homomorphisms Recursive queries and Datalog Selected additional topics: Bag Semantics, Inconsistent Databases Unifying Theme: The interplay between databases, logic, and computational complexity 2 Relational Databases: A Very Brief History The history of relational databases is the history of a scientific and technological revolution. Edgar F. Codd, 1923-2003 The scientific revolution started in 1970 by Edgar (Ted) F. Codd at the IBM San Jose Research Laboratory (now the IBM Almaden Research Center) Codd introduced the relational data model and two database query languages: relational algebra and relational calculus . “A relational model for data for large shared data banks”, CACM, 1970. “Relational completeness of data base sublanguages”, in: Database Systems, ed. by R. Rustin, 1972. 3 Relational Databases: A Very Brief History Researchers at the IBM San Jose Laboratory embark on the System R project, the first implementation of a relational database management system (RDBMS) In 1974-1975, they develop SEQUEL , a query language that eventually became the industry standard SQL . System R evolved to DB2 – released first in 1983. M. Stonebraker and E. Wong embark on the development of the Ingres RDBMS at UC Berkeley in 1973. -

Joining T Joining Tables

44 Joining Tables Chapter Overview This chapter will discuss the concepts and techniques for creating multi-table queries, including joining two subqueries in the FROM clause. SQL can pull information from any number of tables, but for two tables to be used in a query, they must share a com- mon field. The process of creating a multi-table query involves joining tables through their primary key-foreign key relationships. Not all tables have to share the same field, but each table must share a field with at least one other table to form a “relationship chain.” There are different ways to join tables, and the syntax varies among database systems. Chapter Objectives In this chapter, we will: ❍ Study how SQL joins tables ❍ Study how to join tables using an Equi Join ❍ Study how to join tables using an Inner Join ❍ Study the difference between an Inner Join and an Outer Join ❍ Study how to join tables using an Outer Join ❍ Study how to join a table to itself with a Self Join ❍ Study how to join to subqueries in the FROM clause How SQL Joins Tables Consider the two tables below. We’ll step away from Lyric Music for a moment just so we can use smaller sample tables. 66 How SQL Joins Tables 67 Employee Table EmpID FirstName LastName DeptID 1 Tim Wallace Actg 2 Jacob Anderson Mktg 3 Laura Miller Mktg 4 Del Ryan Admn Department Table DeptID DeptName Actg Accounting Admn Administration Fin Finance Mktg Marketing The primary key of the Employee table is EmpID. The primary key of the Department table is DeptID. -

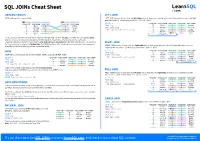

SQL Joins Cheat Sheet

SQL JOINs Cheat Sheet JOINING TABLES LEFT JOIN JOIN combines data from two tables. LEFT JOIN returns all rows from the left table with matching rows from the right table. Rows without a match are filled with NULLs. LEFT JOIN is also called LEFT OUTER JOIN. TOY CAT toy_id toy_name cat_id cat_id cat_name SELECT * toy_id toy_name cat_id cat_id cat_name 1 ball 3 1 Kitty FROM toy 5 ball 1 1 Kitty 2 spring NULL 2 Hugo LEFT JOIN cat 3 mouse 1 1 Kitty 3 mouse 1 3 Sam ON toy.cat_id = cat.cat_id; 1 ball 3 3 Sam 4 mouse 4 4 Misty 4 mouse 4 4 Misty 2 spring NULL NULL NULL 5 ball 1 whole left table JOIN typically combines rows with equal values for the specified columns.Usually , one table contains a primary key, which is a column or columns that uniquely identify rows in the table (the cat_id column in the cat table). The other table has a column or columns that refer to the primary key columns in the first table (thecat_id column in RIGHT JOIN the toy table). Such columns are foreign keys. The JOIN condition is the equality between the primary key columns in returns all rows from the with matching rows from the left table. Rows without a match are one table and columns referring to them in the other table. RIGHT JOIN right table filled withNULL s. RIGHT JOIN is also called RIGHT OUTER JOIN. JOIN SELECT * toy_id toy_name cat_id cat_id cat_name FROM toy 5 ball 1 1 Kitty JOIN returns all rows that match the ON condition.