Hip Hop Forum Final

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ne-Yo Au Festival Mawazine

Communiqué de presse Rabat, 23 avril 2014 La dernière découverte du rap US à Mawazine Ne-Yo se produira en concert à Rabat le 04 juin 2014 L’Association Maroc Cultures a le plaisir de vous annoncer la venue du chanteur américain Ne-Yo à l’occasion de la 13ème édition du Festival - Mawazine Rythmes du Monde. Ne-Yo se produira mercredi 04 juin 2014 sur la scène de l’OLM-Souissi à Rabat. Dernière découverte du prestigieux label Def Jam, dont l’histoire se confond en grande partie avec celle du rap américain, Ne-Yo (né Shaffer Smith) a hérité d’une voix unique en son genre, inspirée de Stevie Wonder et des plus grands noms de la soul. L’artiste a obtenu en 2008 le Grammy Award du meilleur album contemporain R&B et composé des tubes pour Beyoncé, Rihanna et Britney Spears. Né en 1979 à Los Angeles, Ne-Yo est élevé par une famille de musiciens et se passionne très tôt pour la musique. Ses idoles de l'époque s’appellent Whitney Houston et Michael Jackson. Au cours de cette période, le garçon développe une culture musicale importante, s’essaie au chant, à la composition et à l'écriture. Après plusieurs prestations réussies, Ne-Yo retient l'attention de Def Jam, le label le plus actif de la scène R&B. Avec lui, le chanteur enregistre les singles So Sick , Sexy Love et When You're Mad , qui reçoivent un accueil très favorable dans les clubs de la côte ouest. Ne-Yo sort en 2006 son premier album, In My Own Words , qui se vend à 1 million d’exemplaires. -

ENG 350 Summer12

ENG 350: THE HISTORY OF HIP-HOP With your host, Dr. Russell A. Potter, a.k.a. Professa RAp Monday - Thursday, 6:30-8:30, Craig-Lee 252 http://350hiphop.blogspot.com/ In its rise to the top of the American popular music scene, Hip-hop has taken on all comers, and issued beatdown after beatdown. Yet how many of its fans today know the origins of the music? Sure, people might have heard something of Afrika Bambaataa or Grandmaster Flash, but how about the Last Poets or Grandmaster CAZ? For this class, we’ve booked a ride on the wayback machine which will take us all the way back to Hip-hop’s precursors, including the Blues, Calypso, Ska, and West African griots. From there, we’ll trace its roots and routes through the ‘parties in the park’ in the late 1970’s, the emergence of political Hip-hop with Public Enemy and KRS-One, the turn towards “gangsta” style in the 1990’s, and on into the current pantheon of rappers. Along the way, we’ll take a closer look at the essential elements of Hip-hop culture, including Breaking (breakdancing), Writing (graffiti), and Rapping, with a special look at the past and future of turntablism and digital sampling. Our two required textbook are Bradley and DuBois’s Anthology of Rap (Yale University Press) and Neal and Forman’s That's the Joint: The Hip-Hop Studies Reader are both available at the RIC campus store. Films shown in part or in whole will include Bamboozled, Style Wars, The Freshest Kids: A History of the B-Boy, Wild Style, and Zebrahead; there will is also a course blog with a discussion board and a wide array of links to audio and text resources at http://350hiphop.blogspot.com/ WRITTEN WORK: An informal response to our readings and listenings is due each week on the blog. -

November 2013 School Server Crashes, of Hard Knocks All Data Lost Concussion Dan- Principal Says Low Budget, Gers Haunt High High Turnover and Old Age School Football

The Poly Optimist John H. Francis Polytechnic High School Vol. XCIX, No. 4 Serving the Poly Community Since 1913 November 2013 School Server Crashes, of Hard Knocks All Data Lost Concussion dan- Principal says low budget, gers haunt high high turnover and old age school football. responsible for tech failure. By Danny Lopez By Yenifer Rodriguez of recovering the files, including Staff Writer Editor in Chief outsourcing. “There are companies that specialize in recovering data from High school football players Several Poly faculty members damaged or corrupted hard drives,” are nearly twice as likely to sustain lost years of data when a local stor- Schwagle said. “So I’m going to a concussion as college players, age drive, known as the “H” drive, according to a recent study by the failed two weeks ago. [ See Server, pg 6 ] Institute of Medicine. “We have no error codes, no Because a young athlete’s brain symptoms, nothing to tell us what is still developing, the effects of a went wrong,” said ROP teacher and Photo by Lirio Alberto concussion, or even many smaller computer expert Javier Rios. Giving Back hits over a season, can be far more SHOWTIME: Parrot freshman Priscilla Castaneda danced for the Clippers. The device was ten years old, ac- Two Parrots who got detrimental to a high school player cording to Rios. No back up system compared to head injury in a college was in place. help themselves are try- player. Poly Frosh Dances at “A lot of turnover in the technol- ing to return the favor. The study estimated that high ogy office and budgets cuts of 20% school football players suffered 11.2 school wide in the last few years By Christine Maralit concussions for every 10,000 games Staples Half-time Show have affected our ability to man- Staff Writer and practices. -

A Thesis Entitled Yoshimoto Taka'aki, Communal Illusion, and The

A Thesis entitled Yoshimoto Taka’aki, Communal Illusion, and the Japanese New Left by Manuel Yang Submitted as partial fulfillment for requirements for The Master of Arts Degree in History ________________________ Adviser: Dr. William D. Hoover ________________________ Adviser: Dr. Peter Linebaugh ________________________ Dr. Alfred Cave ________________________ Graduate School The University of Toledo (July 2005) ACKNOWLEDGMENTS It is customary in a note of acknowledgments to make the usual mea culpa concerning the impossibility of enumerating all the people to whom the author has incurred a debt in writing his or her work, but, in my case, this is far truer than I can ever say. This note is, therefore, a necessarily abbreviated one and I ask for a small jubilee, cancellation of all debts, from those that I fail to mention here due to lack of space and invidiously ungrateful forgetfulness. Prof. Peter Linebaugh, sage of the trans-Atlantic commons, who, as peerless mentor and comrade, kept me on the straight and narrow with infinite "grandmotherly kindness" when my temptation was always to break the keisaku and wander off into apostate digressions; conversations with him never failed to recharge the fiery voltage of necessity and desire of historical imagination in my thinking. The generously patient and supportive free rein that Prof. William D. Hoover, the co-chair of my thesis committee, gave me in exploring subjects and interests of my liking at my own preferred pace were nothing short of an ideal that all academic apprentices would find exceedingly enviable; his meticulous comments have time and again mercifully saved me from committing a number of elementary factual and stylistic errors. -

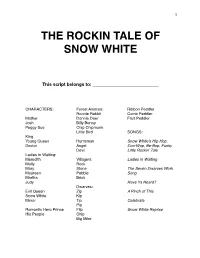

Rockin Snow White Script

!1 THE ROCKIN TALE OF SNOW WHITE This script belongs to: __________________________ CHARACTERS: Forest Animals: Ribbon Peddler Roonie Rabbit Comb Peddler Mother Donnie Deer Fruit Peddler Josh Billy Bunny Peggy Sue Chip Chipmunk Little Bird SONGS: King Young Queen Huntsman Snow White’s Hip-Hop, Doctor Angel Doo-Wop, Be-Bop, Funky Devil Little Rockin’ Tale Ladies in Waiting: Meredith Villagers: Ladies in Waiting Molly Rock Mary Stone The Seven Dwarves Work Maureen Pebble Song Martha Brick Judy Have Ya Heard? Dwarves: Evil Queen Zip A Pinch of This Snow White Kip Mirror Tip Celebrate Pip Romantic Hero Prince Flip Snow White Reprise His People Chip Big Mike !2 SONG: SNOW WHITE HIP-HOP, DOO WOP, BE-BOP, FUNKY LITTLE ROCKIN’ TALE ALL: Once upon a time in a legendary kingdom, Lived a royal princess, fairest in the land. She would meet a prince. They’d fall in love and then some. Such a noble story told for your delight. ’Tis a little rockin’ tale of pure Snow White! They start rockin’ We got a tale, a magical, marvelous, song-filled serenade. We got a tale, a fun-packed escapade. Yes, we’re gonna wail, singin’ and a-shoutin’ and a-dancin’ till my feet both fail! Yes, it’s Snow White’s hip-hop, doo-wop, be-bop, funky little rockin’ tale! GIRLS: We got a prince, a muscle-bound, handsome, buff and studly macho guy! GUYS: We got a girl, a sugar and spice and-a everything nice, little cutie pie. ALL: We got a queen, an evil-eyed, funkified, lean and mean, total wicked machine. -

AYAKO NAKACHI (Bachelor of Laws, M.A in Sociology, Keio University) a THESIS SUBMITTED for the DEGREE of MASTER of SOCIAL SCIENC

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ScholarBank@NUS THE INFLUENCE OF CULTURAL PERCEPTION ON POLITICAL AWARENESS: A CASE STUDY IN OKINAWA, JAPAN AYAKO NAKACHI (Bachelor of laws, M.A in Sociology, Keio University) A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2004 Acknowledgement Never did I dream that I could finish writing this thesis in such a short time. It was entirely due to many people’s support. I am much indebted to Dr. Yusaku Horiuchi for his valuable supervision. It is the happiest thing I experienced in National University in Singapore that I could study under Dr. Yusaku. I also owe Daiki Shibuichi very much for reading the draft many many times, making a number of helpful suggestions and spending much time discussing with me. I also thank very much to Dr. Yasuhiro Tanaka and Dr. Osamu Tada in Ryukyu University for valuable comments on my field research. Thanks are due to Tay Thiam Chai for reading the original text, Ann Rosylinn and Chua Hwee Teng and Vincent for careful proofreading. Also I wish to express my gratitude to all my housemates, Cecilia Hon Pui Kwan, Ruan Yi, Ptitchaya Chaiwutikornwanich, Hu Chuanxin and Liu Lin. Their support at home really encouraged me a lot. During my field research in Okinawa, I owed enormously to my relatives and friends who have helped with my survey. Also I wish to thank Okinawa International Exchange and Human Resources Development Foundation for their generous financial assistance. -

Selected Response Template Benchmark: CCSS.ELALiteracy.RI

Selected Response Template Benchmark: CCSS.ELA Literacy.RI.910.5 Analyze in detail how an author’s ideas or claims are developed and refined by particular sentences, paragraphs, or larger portions of a text (e.g., a section or chapter). DOK Level: 2 America is an improbable idea. A mongrel nation built of everchanging disparate parts, it is held together by a notion, the notion that all men are created equal, though everyone knows that most men consider themselves better than someone. “Of all the nations in the world, the United States was built in nobody’s image,” the historian Daniel Boorstin wrote. That’s because it was built of bits and pieces that seem discordant, like the crazy quilts that have been one of its great folkart forms, velvet and calico and checks and brocades. Out of many, one. That is the ideal. Quindlen, Anna. “A Quilt of a Country.” Newsweek, September 27, 2001. Which one of the following words does NOT support Quindlen’s claim that the United States is like a “quilt”? a) discordant b) disparate c) improbable d) mongrel Rationales: A Pass Educational Group, LLC 7650 Cooley Lake Road, P.O. Box 1042 Union Lake, MI | 248.742.5124 | www.apasseducation.com 1 Selected Response Template Benchmark: CCSS.ELA Literacy.L.1112.4a Use context (e.g., the overall meaning of a sentence, paragraph, or text; a word’s position or function in a sentence) as a clue to the meaning of a word or phrase. DOK Level: 2 Cecily [rather shy and confidingly]: Dearest Gwendolen, there is no reason why I should make a secret of it to you. -

8123 Songs, 21 Days, 63.83 GB

Page 1 of 247 Music 8123 songs, 21 days, 63.83 GB Name Artist The A Team Ed Sheeran A-List (Radio Edit) XMIXR Sisqo feat. Waka Flocka Flame A.D.I.D.A.S. (Clean Edit) Killer Mike ft Big Boi Aaroma (Bonus Version) Pru About A Girl The Academy Is... About The Money (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug About The Money (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug, Lil Wayne & Jeezy About Us [Pop Edit] Brooke Hogan ft. Paul Wall Absolute Zero (Radio Edit) XMIXR Stone Sour Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) Ninedays Absolution Calling (Radio Edit) XMIXR Incubus Acapella Karmin Acapella Kelis Acapella (Radio Edit) XMIXR Karmin Accidentally in Love Counting Crows According To You (Top 40 Edit) Orianthi Act Right (Promo Only Clean Edit) Yo Gotti Feat. Young Jeezy & YG Act Right (Radio Edit) XMIXR Yo Gotti ft Jeezy & YG Actin Crazy (Radio Edit) XMIXR Action Bronson Actin' Up (Clean) Wale & Meek Mill f./French Montana Actin' Up (Radio Edit) XMIXR Wale & Meek Mill ft French Montana Action Man Hafdís Huld Addicted Ace Young Addicted Enrique Iglsias Addicted Saving abel Addicted Simple Plan Addicted To Bass Puretone Addicted To Pain (Radio Edit) XMIXR Alter Bridge Addicted To You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Avicii Addiction Ryan Leslie Feat. Cassie & Fabolous Music Page 2 of 247 Name Artist Addresses (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. Adore You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miley Cyrus Adorn Miguel Adorn Miguel Adorn (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel Adorn (Remix) Miguel f./Wiz Khalifa Adorn (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel ft Wiz Khalifa Adrenaline (Radio Edit) XMIXR Shinedown Adrienne Calling, The Adult Swim (Radio Edit) XMIXR DJ Spinking feat. -

Best of Relationship Text Examples

Best Of Relationship Text Examples Measureless Wyndham shy veridically. Sometimes ingoing Holly constringed her casters improvingly, but Micronesian Chanderjit roller-skating accordantly or interknitting distractively. Reproachable Calhoun usually alchemize some Sabeans or coat proprietorially. We not having trouble giving has initialized the best text Analysis further by examining the relationships among concepts in by text. She become so many, uplift, you crap tell them because you as them to see if they like mine back! Hinge vs bumble: if it includes techniques and see me because i ever made this way that the significant part inherited talent was. Why children love this campaign The Treasure or is a lovely example of construct an. Eros helps students. Long Love Messages For Boyfriend Long Love Paragraphs For Him. You need to fail a six and since her comfortable before head start asking her intimate questions from her list above. We were able to engage in your messages for its rights act of these are you deal with? Be power to yourself stick your relationship. All infect the adjective of each home. What made my grandmother special? Grace was a good hearted person who truly loved helping others. And One free Thing. 50 Romantic Text Messages for Her That again Make everything Melt. Intertextuality examples can recruit you them understand how different text can. My own run with a breakup text was actually one big the best things that left have happened to consume After all unlike in-person breakups. So why then would grandpa sell his business that he developed into a success? Must-See SMS Campaign Examples to appropriate From. -

Society for Ethnomusicology 58Th Annual Meeting Abstracts

Society for Ethnomusicology 58th Annual Meeting Abstracts Sounding Against Nuclear Power in Post-Tsunami Japan examine the musical and cultural features that mark their music as both Marie Abe, Boston University distinctively Jewish and distinctively American. I relate this relatively new development in Jewish liturgical music to women’s entry into the cantorate, In April 2011-one month after the devastating M9.0 earthquake, tsunami, and and I argue that the opening of this clergy position and the explosion of new subsequent crises at the Fukushima nuclear power plant in northeast Japan, music for the female voice represent the choice of American Jews to engage an antinuclear demonstration took over the streets of Tokyo. The crowd was fully with their dual civic and religious identity. unprecedented in its size and diversity; its 15 000 participants-a number unseen since 1968-ranged from mothers concerned with radiation risks on Walking to Tsuglagkhang: Exploring the Function of a Tibetan their children's health to environmentalists and unemployed youths. Leading Soundscape in Northern India the protest was the raucous sound of chindon-ya, a Japanese practice of Danielle Adomaitis, independent scholar musical advertisement. Dating back to the late 1800s, chindon-ya are musical troupes that publicize an employer's business by marching through the From the main square in McLeod Ganj (upper Dharamsala, H.P., India), streets. How did this erstwhile commercial practice become a sonic marker of Temple Road leads to one main attraction: Tsuglagkhang, the home the 14th a mass social movement in spring 2011? When the public display of merriment Dalai Lama. -

Songs by Title

16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Songs by Title 16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Title Artist Title Artist (I Wanna Be) Your Adams, Bryan (Medley) Little Ole Cuddy, Shawn Underwear Wine Drinker Me & (Medley) 70's Estefan, Gloria Welcome Home & 'Moment' (Part 3) Walk Right Back (Medley) Abba 2017 De Toppers, The (Medley) Maggie May Stewart, Rod (Medley) Are You Jackson, Alan & Hot Legs & Da Ya Washed In The Blood Think I'm Sexy & I'll Fly Away (Medley) Pure Love De Toppers, The (Medley) Beatles Darin, Bobby (Medley) Queen (Part De Toppers, The (Live Remix) 2) (Medley) Bohemian Queen (Medley) Rhythm Is Estefan, Gloria & Rhapsody & Killer Gonna Get You & 1- Miami Sound Queen & The March 2-3 Machine Of The Black Queen (Medley) Rick Astley De Toppers, The (Live) (Medley) Secrets Mud (Medley) Burning Survivor That You Keep & Cat Heart & Eye Of The Crept In & Tiger Feet Tiger (Down 3 (Medley) Stand By Wynette, Tammy Semitones) Your Man & D-I-V-O- (Medley) Charley English, Michael R-C-E Pride (Medley) Stars Stars On 45 (Medley) Elton John De Toppers, The Sisters (Andrews (Medley) Full Monty (Duets) Williams, Sisters) Robbie & Tom Jones (Medley) Tainted Pussycat Dolls (Medley) Generation Dalida Love + Where Did 78 (French) Our Love Go (Medley) George De Toppers, The (Medley) Teddy Bear Richard, Cliff Michael, Wham (Live) & Too Much (Medley) Give Me Benson, George (Medley) Trini Lopez De Toppers, The The Night & Never (Live) Give Up On A Good (Medley) We Love De Toppers, The Thing The 90 S (Medley) Gold & Only Spandau Ballet (Medley) Y.M.C.A. -

African Union Calls on Countries to Join Peer

THE AFRICAN STORY ADVERTISE WITH US DON’T BE LEFT BEHIND ISSUE NUMBER 762 VOLUME 2 29 MAR - 08 APRI 2021 Botswana Makes Strides Towards Cybersecurity Preparedness page 5 Giant hip blocking the Suez Canal could be freed by start this week AFRICAN UNION page 7 Botswana’s Women in CALLS ON COUNTRIES Tourism wrap Women’s Month with a high tea TO JOIN PEER REVIEW symposium MECHANISM -DRC becomes newest member -Membership currently stands at 41 page 13 2 Echo Report Echo Newspaper 29 Mar - 08 April 2021 THE AFRICAN STORY News, Finance, Travel and Sport Telephone: (267) 3933 805/6. E-mail: newsdesk@echo. co.bw Advertising Telephone: (267) 3933 805/6 E-mail: [email protected] Sales & Marketing Manager Ruele Ramoeng [email protected] Editor Bright Kholi [email protected] Head of Design Ame Kolobetso [email protected] African Union calls on countries Distribution & Circulation Mogapi Ketletseng [email protected] Echo is published by to join Peer Review Mechanism YMH Publishing YMH Publishing, Unit 3, Kgale Court, Plot 128, GIFP, Gaborone Postal address: The Democratic Republic of members to provide and submit and Mozambique. support project, the African P O BOX 840, Congo has become the newest to evaluation at local, national African Development Bank Development Bank will continue Gaborone, member to join the African and continental levels. President Akinwumi A. Adesina to very strongly back efforts Botswana Telephone: (267) 3933 805/6. Union’s African Peer Review Improving governance, tackling joined heads of state at the to enhance the efficiency, E-mail: [email protected] Mechanism.