Newsletter 26

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ELECTORAL DIVISION PROFILE 2017 This Division Comprises Bungay and Wainford Wards in Their Entirety Plus Part of the Saints Ward

UNGAY ELECTORAL DIVISION PROFILE 2017 This Division comprises Bungay and Wainford wards in their entirety plus part of The Saints ward www.suffolkobservatory.info 2 © Crown copyright and database rights 2017 Ordnance Survey 100023395 CONTENTS . Demographic Profile: Age & Ethnicity . Economy and Labour Market . Schools & NEET . Index of Multiple Deprivation . Health . Crime & Community Safety . Additional Information . Data Sources 3 ELECTORAL DIVISION PROFILES: AN INTRODUCTION These profiles have been produced to support elected members, constituents and other interested parties in understanding the demographic, economic, social and educational profile of their neighbourhoods. We have used the latest data available at the time of publication. Much more data is available from national and local sources than is captured here, but it is hoped that the profile will be a useful starting point for discussion, where local knowledge and experience can be used to flesh out and illuminate the information presented here. The profile can be used to help look at some fundamental questions e.g. Does the age profile of the population match or differ from the national profile? . Is there evidence of the ageing profile of the county in all the wards in the Division or just some? . How diverse is the community in terms of ethnicity? . What is the impact of deprivation on families and residents? . Does there seem to be a link between deprivation and school performance? . What is the breakdown of employment sectors in the area? . Is it a relatively healthy area compared to the rest of the district or county? . What sort of crime is prevalent in the community? A vast amount of additional data is available on the Suffolk Observatory www.suffolkobservatory.info The Suffolk Observatory is a free online resource that contains all Suffolk’s vital statistics; it is the one‐stop‐shop for information and intelligence about Suffolk. -

Suffolk County Council Lake Lothing Third Crossing Application for Development Consent Order

Lake Lothing Third Crossing Consultation Report Document Reference: 5.1 The Lake Lothing (Lowestoft) Third Crossing Order 201[*] _________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________ Document 5.2: Consultation Report Appendices Appendix 13 List of Non-statutory Consultees _________________________________________________________________________ Author: Suffolk County Council Lake Lothing Third Crossing Application for Development Consent Order Document Reference: 5.2 Consultation Report appendices THIS PAGE HAS INTENTIONALLY BEEN LEFT BLANK 2 Lake Lothing Third Crossing Application for Development Consent Order Document Reference: 5.2 Consultation Report Appendices Consultation Report Appendix 13 List of non-statutory consultees Lake Lothing Third Crossing Application for Development Consent Order Document Reference: 5.2 Consultation Report Appendices THIS PAGE HAS INTENTIONALLY BEEN LEFT BLANK Lake Lothing Third Crossing Application for Development Consent Order Document Reference: 5.2 Consultation Report Appendices All Saints and St Forestry Commission Suffolk Advanced Motorcyclists Nicholas, St Michael and St Peter South Elmham Parish Council Ashby, Herringfleet and Freestones Coaches Ltd Suffolk Amphibian & Reptile Group Somerleyton Parish Council Barnby Parish Council Freight Transport Suffolk Archaeology Association Barsham & Shipmeadow Friends of Nicholas Suffolk Biological Records Centre Parish Council Everitt Park Beccles Town Council -

Housing Stock for Suffolk's Districts and Parishes 2003

HOUSING STOCK FOR SUFFOLK’S DISTRICTS AND PARISHES 2003-2012 Prepared by Business Development 0 Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................ 2 Section 1 – Introduction ................................................................................................................ 2 Section 2 – Data ................................................................................................................................ 3 County and District ..................................................................................................................... 3 Babergh ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Forest Heath .................................................................................................................................. 7 Ipswich (and Ipswich Policy Area) ....................................................................................... 8 Mid Suffolk ..................................................................................................................................... 9 St Edmundsbury ........................................................................................................................ 12 Suffolk Coastal ............................................................................................................................ 15 Waveney ...................................................................................................................................... -

Full Responses to Sites

Help plan our future: Options for the new Waveney Local Plan Responses to Sites August 2016 Help plan our future: Options for the new Waveney Local Plan Responses to Sites August 2016 1 - 19-21 Ravensmere, Beccles ....................................................................................................... 6 2 - Allotment land, Somerleyton ..................................................................................................... 6 3 - Ashfield Stables, Hall Lane, Oulton ............................................................................................ 9 4 - Blundeston Road (west end), Blundeston ................................................................................. 9 5 - Brambles Drift, Green Lane, Reydon ....................................................................................... 11 6 - Broadside Park Farm, Reydon .................................................................................................. 13 7 - Burnt Hill Lane to Marsh Lane, Carlton Colville /Lowestoft ..................................................... 15 8 - Chenery's Land (East), Cucumber Lane, Beccles / Land at Chenery's Farm, Beccles ............... 18 9 - Chenery's Land (West), Cucumber Lane, Beccles / Land at Chenery's Farm, Beccles ............. 23 13 - Fairview Farm, Norwich Road, Halesworth / Holton ............................................................. 28 14 - Field, Saxon Way, Halesworth ............................................................................................... 30 15 -

East Suffolk Parliamentary Constituencies

East Suffolk - Parliamentary Constituencies East Suffolk Council Scale Crown Copyright, all rights reserved. Scale: 1:70000 0 800 1600 2400 3200 4000 m Map produced on 26 November 2018 at 10:55 East Suffolk Council LA 100019684 Lound CP Somerleyton, Ashby and Herringfleet CP Corton Blundeston CP Flixton CP Oulton CP Lowestoft Oulton Broad Carlton Colville CP Barnby CP Beccles CP Mettingham CP Worlingham CP North Cove CP Shipmeadow CP Barsham CP Bungay CP Mutford CP Gisleham CP St. John, Ilketshall CP Rushmere CP Ellough CP Ringsfield CP Weston CP Kessingland CP Flixton CP Waveney Constituency St. Andrew, Ilketshall CP Henstead with Hulver Street CP Willingham St. Mary CP St. Mary, South Elmham Otherwise Homersfield CP St. Margaret, Ilketshall CP St. Lawrence, Ilketshall CP Sotterley CP St. Peter, South Elmham CP Redisham CP Shadingfield CP St. Margaret, South Elmham CP Benacre CP St. Cross, South Elmham CP St. Michael, South Elmham CP Wrentham CP All Saints and St. Nicholas, South Elmham CP Brampton with Stoven CP Rumburgh CP Frostenden CP Covehithe CP Westhall CP Spexhall CP St. James, South Elmham CP Uggeshall CP South Cove CP Wissett CP Sotherton CP Holton CP Wangford with Henham CP Chediston CP Reydon CP Linstead Parva CP Blyford CP Halesworth CP Linstead Magna CP Southwold CP Cookley CP Wenhaston with Mells Hamlet CP Cratfield CP Huntingfield CP Walberswick CP Blythburgh CP Walpole CP Bramfield CP Thorington CP Ubbeston CP Heveningham CP Dunwich CP Darsham CP Sibton CP Peasenhall CP Westleton CP Yoxford CP Dennington CP Badingham CP Middleton CP Bruisyard CP Rendham CP Saxtead CP Kelsale cum Carlton CP Cransford CP Theberton CP Swefling CP Leiston CP Framlingham CP Earl Soham CP Saxmundham CP Central Suffolk & North Ipswich Great Glemham CP Kettleburgh CP Constituency Benhall CP Knodishall CP Brandeston CP Parham CP Sternfield CP Aldringham cum Thorpe CP Stratford St. -

Halesworth January 2018

January 2018 Halesworth You said... We did... There were continuing Research into longterm concerns surrounding solutions, including work parking issues outside some around RESPECT ZONES. local schools. We will be launching this project shortly and promoting to local schools. Responding to issues in your community Reports of counterfeit currency being passed to local businesses. SNT worked to highlight this issue in the Southwold area through letter drops, social media and linking in with the local business association. Future events Making the community safer Visit to Sibton Primary School to allow youngsters to meet and Having seen an increase in theft talk to uniformed officers. This was an opportunity to discuss related crime where power tools personal safety and road safety with a particular emphasis on have been targeted our team will wearing bright clothing in the winter months. be working with the community to raise awareness of the issue and BE SAFE BE SEEN. advise on how you can mark your valuable property. Preventing, reducing and solving crime and ASB T. Tell employees, friends, family. A. Accurately record serial ID's. Sotherton/Reydon - Partnership working with local housing G. Get your property marked. providers to tackle and reduce reported ASB and harassment concerns, linking in with housing officers to explore longterm Please visit our web page for full solutions to re-occurring issues. crime prevention details. This SNT covers the following parishes All Saints & St. Nicholas, South Elmham, Benacre, Blyford, Blythburgh, Bramfield, Brampton with Stoven, Chediston, Cookley, Covehithe, Cratfield, Darsham, Dunwich, Flixton, Frostenden, Halesworth, Henstead with Hulver Street, Heveningham, Holton, Homersfield, Huntingfield, Linstead Magna, Linstead Parva,Peasenhall, Reydon, Rumburgh, Rushmere, Sibton, Sotherton, South Cove, Southwold, Spexhall, St. -

Three Rivers Talking Newspaper Word

Three Rivers Talking Newspaper Twenty-one years old: The story so far Friday, June 21st, 1991, was the day the first edition of the Three Rivers Talking Newspaper was produced on cassette tapes and dispatched by post to the homes of 87 blind or partially-sighted people living on the Suffolk and Norfolk sides of the Waveney Valley. The three rivers in the title reflected the district from which news would be covered by the new TN -- the Waveney at Beccles, Bungay and Harleston, the Blyth at Halesworth and Southwold and the Chet at Loddon. This is the circulation area of the Beccles and Bungay Journal from which permission was obtained to record its contents for distribution to our listeners. Why did it happen? Sound East, the TN for the Lowestoft area, had received complaints that its news coverage did not extend to the Beccles, Bungay, Loddon and Halesworth district. As a result, Sound East decided to assist with the setting-up of a new talking newspaper in this area. and organised a number of meetings at various venues, including one in the Village Hall at St James South Elmham, during the latter part of 1990, to publicise the project and confirm the interest in and demand for such a service. Consequently, Sound East called a meeting at Beccles in February, 1991, and a steering committee was born. It consisted of David Wuyts chairman, Kath Bird secretary, Joan Wuyts treasurer, John Pickett co-ordinator, Tony Clarke publicity and Gillian Wright fund-raising. In due course we had four teams of seven volunteers ready to start training by members of Sound East. -

Halesworth December 2018

December 2018 Halesworth You said... We did... You wanted us to deal with In co-operation with the issues giving rise to Halesworth Town Council, the anti-social behaviour as well SNT have been liaising with as the ASB itself. partners to develop joint approaches into the causes of ASB Responding to issues in your community Staying on the theme of joint partnership working, the SNT has been employed during November working with associate groups to safeguard the welfare of a vulnerable victim of domestic abuse. This is a good example of the 'hidden' work we do after a crime has occurred to try & reduce the risks, threats & harm to victims and prevent them being targeted again. Future events Making the community safer Just a reminder that this years' The SNT have been visiting primary schools in the area during Christmas Drink / Drive November to develop plans around 'lock-down' procedures. campaign has already begun. These are the actions schools take if they face threats of A new theme has been various kinds where children &/or staff would be at risk. adopted for 2018 named 'Not We have been advising the schools what actions to take and The Usual Suspects' . how to implement agreed actions if faced with such threats. It hopes to highlight the fact that a drink driver can in-fact be from any type of background Preventing, reducing and solving crime and ASB and will not necessarily Crime reduction has been high on our agenda, after a number of conform to stereotypes. It not elderly victims were targeted by telephone scams, resulting in some only appeals to those who think having large sums of cash stolen along with bank account details. -

East Suffolk County Divisions

East Suffolk - County Divisions East Suffolk Council Scale Crown Copyright, all rights reserved. Scale: 1:70000 0 800 1600 2400 3200 4000 m Map produced on 26 November 2018 at 10:30 East Suffolk Council LA 100019684 Lound CP Somerleyton, Ashby and Herringfleet CP Corton OULTONBlundeston CP Flixton CP GUNTON Oulton CP Lowestoft Oulton Broad LOWESTOFT SOUTH Carlton PAKEFIELDColville CP Barnby CP Beccles CP BECCLES Mettingham CP Worlingham CP North Cove CP Shipmeadow CP Barsham CP Bungay CP Mutford CP Gisleham CP St. John, Ilketshall CP Rushmere CP Ellough CP Ringsfield CP Weston CP Flixton CP Kessingland CP BUNGAYSt. Andrew, Ilketshall CP Henstead with Hulver Street CP Willingham St. Mary CP St. Mary, South Elmham Otherwise Homersfield CP St. Margaret, IlketshallSt. Lawrence, CP Ilketshall CP St. Peter, South Elmham CP Sotterley CP Redisham CP Shadingfield CP St. Margaret, South Elmham CP Benacre CP St. Cross, South Elmham CP St. Michael, South Elmham CP WrenthamKESSINGLAND CP AND SOUTHWOLD All Saints and St. Nicholas, South Elmham CP Brampton with Stoven CP Rumburgh CP Frostenden CP Westhall CP Covehithe CP Spexhall CP St. James, South Elmham CP Uggeshall CP HALESWORTH South Cove CP Wissett CP Sotherton CP Holton CP Wangford with Henham CP Chediston CP Reydon CP Linstead Parva CP Blyford CP Halesworth CP Linstead Magna CP Cookley CP Southwold CP Wenhaston with Mells Hamlet CP Cratfield CP Huntingfield CP Walberswick CP Blythburgh CP Walpole CP Bramfield CP Thorington CP Ubbeston CP Heveningham CP Dunwich CP Darsham CPBLYTHING Sibton CP Peasenhall CP Westleton CP Yoxford CP Dennington CP FRAMLINGHAM Badingham CP Middleton CP Bruisyard CP Kelsale cum Carlton CP Saxtead CP Rendham CP Cransford CP Theberton CP Swefling CP Leiston CP Framlingham CP Earl Soham CP Saxmundham CP Great Glemham CP Benhall CP Knodishall CP ALDEBURGH AND LEISTON Kettleburgh CP Parham CP Sternfield CP Brandeston CP Aldringham cum Thorpe CP Stratford St. -

Parish Share 2021

Parish Share 2021 Deanery Summary: 28 February 2021 29th February Deanery Received 2020 Received Clare £ 9,574 £ 14,582 Gipping Valley £ 67,109 £ 95,058 Hadleigh £ 13,409 £ 31,772 Ixworth £ 13,388 £ 16,755 Lavenham £ 42,024 £ 38,734 Mildenhall £ 16,483 £ 19,781 Sudbury £ 39,197 £ 32,414 Thingoe £ 79,127 £ 77,186 Sudbury Archdeaconry £ 280,311 £ 326,282 Colneys £ 54,479 £ 66,254 Hartismere £ 15,289 £ 21,384 Hoxne £ 9,110 £ 15,569 Loes £ 21,994 £ 42,071 Samford £ 15,972 £ 16,199 Saxmundham £ 35,181 £ 48,089 Waveney & Blyth £ 46,260 £ 52,586 Woodbridge £ 44,720 £ 62,613 Suffolk Archdeaconry £ 243,005 £ 324,766 Ipswich £ 76,329 £ 63,850 Ipswich Archdeaconry £ 76,329 £ 63,850 Other Donations £ 490 £ - February 2021 /2020 £ 600,135 £ 714,897 05/05/2021 P:\Accounts General\Parish Share\2021\Reports\Share Report-Funds Received as at 28th February 2021 Parish Share 2021 Clare Deanery: 2021 Parish/Benefice Received Haverhill £ - Withersfield £ - Waiver agreed by Finance Committee Haverhill with Withersfield Total £ - Barnardiston £ - Great Bradley £ - Great Thurlow £ - Great Wratting £ - Kedington £ - Little Bradley £ - Little Thurlow £ - Little Wratting £ - Under-allocation £ - Stourhead Benefice Total £ - Cowlinge £ - Denston £ - Lidgate £ - Ousden £ 1,000 Stansfield £ - Stradishall £ - Wickhambrook £ 800 To be allocated The Benefice of Bansfield Total £ 1,800 Chedburgh £ - Chevington £ 2,536 Depden £ - Hargrave £ 500 Hawkedon £ 1,238 Rede £ - The Benefice of Suffolk Heights Total £ 4,274 Cavendish £ - Clare with Poslingford £ 3,500 Hundon £ -

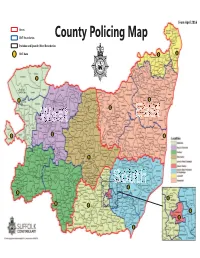

County Policing Map

From April 2016 Areas Somerleyton, Ashby and Herringfleet SNT Boundaries County Policing Map Parishes and Ipswich Ward Boundaries SNT Base 17 18 North Cove Shipmeadow Ilketshall St. John Ilketshall St. Andrew Ilketshall St. Lawrence St. Mary, St. Margaret South Ilketshall Elmham, Henstead with Willingham St. May Hulver Street St. Margaret, South Elmham St. Peter, South ElmhamSt. Michael, South Elmham HomersfieldSt. Cross, South Elmham All Saints and 2 St. Nicholas, South Elmham St. James, South Elmham Beck Row, Holywell Row and Kenny Hill Linstead Parva Linstead Magna Thelnetham 14 1 Wenhaston with Mildenhall Mells Hamlet Southwold Rickinghall Superior 16 Rickinghall Inferior Thornham Little Parva LivermLivermore Ixworthxwo ThorpeThorp Thornham Magna Athelington St.S GenevieveFornhamest Rishangles Fornham All Saints Kentford 4 3 15 Wetheringsett cum Brockford Old Newton Ashfield cum with Thorpe Dagworth Stonham Parva Stratford Aldringham Whelnetham St. Andrew Little cum Thorpe Brandeston Whelnetham Great Creeting St. Peter Chedburgh Gedding Great West Monewden Finborough 7 Creeting Bradfield Combust with Stanningfield Needham Market Thorpe Morieux Brettenham Little Bradley Somerton Hawkedon Preston Kettlebaston St. Mary Great Blakenham Barnardiston Little BromeswellBrome Blakenham ut Sutton Heath Little Little 12 Wratting Bealings 6 Flowton Waldringfield Great 9 Waldingfield 5 Rushmere St. Andrew 8 Chattisham Village Wenham Magna 11 Stratton Hall 10 Rushmere St. Andrew Town Stratford Trimley St. Mary St. Mary 13 Erwarton Clare Needham Market Sproughton Melton South Cove Bedingfi eld Safer Neighbourhood Cowlinge Nettlestead Stoke-by-Nayland Orford Southwold Braiseworth Denston Norton Stratford St. Mary Otley Spexhall Brome and Oakley Teams and parishes Depden Offton Stutton Pettistree St. Andrew, Ilketshall Brundish Great Bradley Old Newton with Tattingstone Playford St. -

English Nature Research Report

Table 7 1 ~ Pond density in the East Anglian Plain Natural Area. In alphabetical order of pkename. number area of ponds District or Natural Area Parish of ponds parish [ha) per sq krn Borough Acton 50 1370.1 4.3 Babergh East Angiian Plain Ake nh a m 14 432.9 3.2 Mid Suffolk East Anglian Plain Aidharn 49 667.2 7.3 Baberg h East Anglian Plain All Saints and St Nicholas South Elmham 94 664.5 14.1 Waveney East Anglian Plain Afpheton 22 493.9 4.5 Babergh East Angkan Plain Ash bocking 64 571.7 11.2 Mid Suffolk East Anglian Plain Ashfietd curn Thorpe 57 639.4 8.9 Mid Suffolk East Anglian Plain Aspatl 34 341.3 10.0 Mid Suffolk East Anglian Plain Assi ngton 44 1120.0 3.9 Babergh East Anglian Plain At helington 25 200.0 12.5 Mid Suffotk East Anglian Plain Bacton i08 923.4 1I .I Mid Suffolk East Anglian Plain Badingham I67 1299.8 $2.8 Suffolk Coastal East Anglian Pfairr Badley 27 436.7 6.2 Mid Suffolk East Anglian Plain Badwell Ash 78 151.5 10.4 Mid Suffotk East Anglian Plain 8ardwell 41 997.4 4.1 St Edmundsbury East Angliafl Piain Barham 46 729.3 6.3 Raid Suffolk East Anglian Plain Barking 89 1275.1 7.0 Mid Suffolk East Angtian Plain Barnardiston 14 50&9 2.8 St Edmundsbury East Anglian Pfain Barningharn 44 532.5 8.3 St Edrnundsbury East Anglian Plain Barrow 43 1085.0 3.8 St Edrnundsbury East Anglian Plain €3att isfo rd 43 539.9 6.7 Mid Suffolk East Anglian Plain Baylham 35 549.3 6.4 Mid Suffolk East Anglian Plain Bedfield 85 51 3.9 $6.5 Mid Suffolk East Angkian Plain Bedingfield 66 730.7 9.0 Mid Suffotk East Angiian Plain Betstead I3 305.8 4.3 Babergh