User Tracking in the Post-Cookie Era: How Websites Bypass GDPR Consent to Track Users Please Cite Our WWW’2021 Paper, Doi: 10.1145/3442381.3450056

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Web Never Forgets: Persistent Tracking Mechanisms in the Wild

The Web Never Forgets: Persistent Tracking Mechanisms in the Wild Gunes Acar1, Christian Eubank2, Steven Englehardt2, Marc Juarez1 Arvind Narayanan2, Claudia Diaz1 1KU Leuven, ESAT/COSIC and iMinds, Leuven, Belgium {name.surname}@esat.kuleuven.be 2Princeton University {cge,ste,arvindn}@cs.princeton.edu ABSTRACT 1. INTRODUCTION We present the first large-scale studies of three advanced web tracking mechanisms — canvas fingerprinting, evercookies A 1999 New York Times article called cookies compre and use of “cookie syncing” in conjunction with evercookies. hensive privacy invaders and described them as “surveillance Canvas fingerprinting, a recently developed form of browser files that many marketers implant in the personal computers fingerprinting, has not previously been reported in the wild; of people.” Ten years later, the stealth and sophistication of our results show that over 5% of the top 100,000 websites tracking techniques had advanced to the point that Edward employ it. We then present the first automated study of Felten wrote “If You’re Going to Track Me, Please Use Cook evercookies and respawning and the discovery of a new ev ies” [18]. Indeed, online tracking has often been described ercookie vector, IndexedDB. Turning to cookie syncing, we as an “arms race” [47], and in this work we study the latest present novel techniques for detection and analysing ID flows advances in that race. and we quantify the amplification of privacy-intrusive track The tracking mechanisms we study are advanced in that ing practices due to cookie syncing. they are hard to control, hard to detect and resilient Our evaluation of the defensive techniques used by to blocking or removing. -

Add a Captcha to a Contact Form

Add A Captcha To A Contact Form Colin is swishing: she sectionalizing aphoristically and netts her wherefore. Carroll hogtying opportunely while unresolved Tre retell uncontrollably or trekking point-device. Contractible Howard cravatted her merrymakers so afire that Hugo stabilised very microscopically. Please provide this works just create customized contact form module that you can add a captcha to contact form element options can process Are seldom sure you want to excuse that? It was looking at minimum form now it to both nithin and service will be used by my front end. Or two parameters but without much! Bleeding edge testing system that controls the add a captcha contact form to. Allows you ever want to disable any spam form script that you to add and choose themes that have a contact form or badge or six letters! Even for contact template tab we work fine, add a plugin. Captcha your print perfectly clear explanation was more traditional captcha as a mix of images with no clue how do exactly what is a contact your website? Collect information and is not backward compatible with a captcha to form orders and legally hide it? Is there a way to gauge my Mac from sleeping during a file copy? Drop the Contact Form element on your desired area. Captcha widget areas in your site. How can never change the production method my products use? Honeypots are essential for our ads for us understand what you have a template is now has a weird of great option only use? This full stack overflow! The mail is sent, email and a message field. -

The Internet and Web Tracking

Grand Valley State University ScholarWorks@GVSU Technical Library School of Computing and Information Systems 2020 The Internet and Web Tracking Tim Zabawa Grand Valley State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/cistechlib ScholarWorks Citation Zabawa, Tim, "The Internet and Web Tracking" (2020). Technical Library. 355. https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/cistechlib/355 This Project is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Computing and Information Systems at ScholarWorks@GVSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Technical Library by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@GVSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tim Zabawa 12/17/20 Capstone Project Cover Page: 1. Introduction 2 2. How we are tracked online 2 2.1 Cookies 3 2.2 Browser Fingerprinting 4 2.3 Web Beacons 6 3. Defenses Against Web Tracking 6 3.1 Cookies 7 3.2 Browser Fingerprinting 8 3.3 Web Beacons 9 4. Technological Examples 10 5. Why consumer data is sought after 27 6. Conclusion 28 7. References 30 2 1. Introduction: Can you remember the last time you didn’t visit at least one website throughout your day? For most people, the common response might be “I cannot”. Surfing the web has become such a mainstay in our day to day lives that a lot of us have a hard time imagining a world without it. What seems like an endless trove of data is right at our fingertips. On the surface, using the Internet seems to be a one-sided exchange of information. We, as users, request data from companies and use it as we deem fit. -

Privacy Policy Interpretation and Definitions

Privacy Policy This Privacy Policy describes Our policies and procedures on the collection, use and disclosure of Your information when You use the Service and tells You about Your privacy rights and how the law protects You. We use Your Personal data to provide and improve the Service. By using the Service, You agree to the collection and use of information in accordance with this Privacy Policy. Interpretation and Definitions Interpretation The words of which the initial letter is capitalized have meanings defined under the following conditions. The following definitions shall have the same meaning regardless of whether they appear in singular or in plural. Definitions For the purposes of this Privacy Policy: • You means the individual accessing or using the Service, or the company, or other legal entity on behalf of which such individual is accessing or using the Service, as applicable. Under GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation), You can be referred to as the Data Subject or as the User as you are the individual using the Service. • Company (referred to as either "the Company", "We", "Us" or "Our" in this Agreement) refers to Adventure City Inc., 1238 S. BEACH BLVD., SUITE E. For the purpose of the GDPR, the Company is the Data Controller. • Affiliate means an entity that controls, is controlled by or is under common control with a party, where "control" means ownership of 50% or more of the shares, equity interest or other securities entitled to vote for election of directors or other managing authority. • Account means a unique account created for You to access our Service or parts of our Service. -

Improving Transparency Into Online Targeted Advertising

AdReveal: Improving Transparency Into Online Targeted Advertising Bin Liu∗, Anmol Sheth‡, Udi Weinsberg‡, Jaideep Chandrashekar‡, Ramesh Govindan∗ ‡Technicolor ∗University of Southern California ABSTRACT tous and cover a large fraction of a user’s browsing behav- To address the pressing need to provide transparency into ior, enabling them to build comprehensive profiles of their the online targeted advertising ecosystem, we present AdRe- online interests. This widespread tracking of users and the veal, a practical measurement and analysis framework, that subsequent personalization of ads have received a great deal provides a first look at the prevalence of different ad target- of negative press; users associate adjectives such as creepy ing mechanisms. We design and implement a browser based and scary with the practice [18], primarily because they lack tool that provides detailed measurements of online display insight into how their data is being collected and used. ads, and develop analysis techniques to characterize the con- Our paper seeks to provide transparency into the targeted textual, behavioral and re-marketing based targeting mecha- advertising ecosystem, a capability that has not been ex- nisms used by advertisers. Our analysis is based on a large plored so far. We seek to enable end-users to reason about dataset consisting of measurements from 103K webpages why ads of a certain category are being displayed to them. and 139K display ads. Our results show that advertisers fre- Consider a user that repeatedly receives ads about cures for a quently target users based on their online interests; almost particularly private ailment. The user currently lacks a way half of the ad categories employ behavioral targeting. -

Cookie Swap Party: Abusing First-Party Cookies for Web Tracking

Cookie Swap Party: Abusing First-Party Cookies for Web Tracking Quan Chen Panagiotis Ilia [email protected] [email protected] North Carolina State University University of Illinois at Chicago Raleigh, USA Chicago, USA Michalis Polychronakis Alexandros Kapravelos [email protected] [email protected] Stony Brook University North Carolina State University Stony Brook, USA Raleigh, USA ABSTRACT 1 INTRODUCTION As a step towards protecting user privacy, most web browsers perform Most of the JavaScript (JS) [8] code on modern websites is provided some form of third-party HTTP cookie blocking or periodic deletion by external, third-party sources [18, 26, 31, 38]. Third-party JS li- by default, while users typically have the option to select even stricter braries execute in the context of the page that includes them and have blocking policies. As a result, web trackers have shifted their efforts access to the DOM interface of that page. In many scenarios it is to work around these restrictions and retain or even improve the extent preferable to allow third-party JS code to run in the context of the of their tracking capability. parent page. For example, in the case of analytics libraries, certain In this paper, we shed light into the increasingly used practice of re- user interaction metrics (e.g., mouse movements and clicks) cannot lying on first-party cookies that are set by third-party JavaScript code be obtained if JS code executes in a separate iframe. to implement user tracking and other potentially unwanted capabil- This cross-domain inclusion of third-party JS code poses security ities. -

Analysis and Detection of Spying Browser Extensions

I Spy with My Little Eye: Analysis and Detection of Spying Browser Extensions Anupama Aggarwal⇤, Bimal Viswanath†, Liang Zhang‡, Saravana Kumar§, Ayush Shah⇤ and Ponnurangam Kumaraguru⇤ ⇤IIIT - Delhi, India, email: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] †UC Santa Barbara, email: [email protected] ‡Northeastern University, email: [email protected] §CEG, Guindy, India, email: [email protected] Abstract—In this work, we take a step towards understanding history) and sends the information to third-party domains, and defending against spying browser extensions. These are when its core functionality does not require such information extensions repurposed to capture online activities of a user communication (Section 3). Such information theft is a and communicate the collected sensitive information to a serious violation of user privacy. For example, a user’s third-party domain. We conduct an empirical study of such browsing history can contain URLs referencing private doc- extensions on the Chrome Web Store. First, we present an in- uments (e.g., Google docs) or the URL parameters can depth analysis of the spying behavior of these extensions. We reveal privacy sensitive activities performed by the user on observe that these extensions steal a variety of sensitive user a site (e.g., online e-commerce transactions, password based information, such as the complete browsing history (e.g., the authentication). Moreover, if private data is further sold or sequence of web traversals), online social network (OSN) access exchanged with cyber-criminals [4], it can be misused in tokens, IP address, and geolocation. Second, we investigate numerous ways. -

Track the Planet: a Web-Scale Analysis of How Online Behavioral Advertising Violates Social Norms

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2017 Track The Planet: A Web-Scale Analysis Of How Online Behavioral Advertising Violates Social Norms Timothy Patrick Libert University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Communication Commons, Computer Sciences Commons, and the Public Policy Commons Recommended Citation Libert, Timothy Patrick, "Track The Planet: A Web-Scale Analysis Of How Online Behavioral Advertising Violates Social Norms" (2017). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2714. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2714 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2714 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Track The Planet: A Web-Scale Analysis Of How Online Behavioral Advertising Violates Social Norms Abstract Various forms of media have long been supported by advertising as part of a broader social agreement in which the public gains access to monetarily free or subsidized content in exchange for paying attention to advertising. In print- and broadcast-oriented media distribution systems, advertisers relied on broad audience demographics of various publications and programs in order to target their offers to the appropriate groups of people. The shift to distributing media on the World Wide Web has vastly altered the underlying dynamic by which advertisements are targeted. Rather than rely on imprecise demographics, the online behavioral advertising (OBA) industry has developed a system by which individuals’ web browsing histories are covertly surveilled in order that their product preferences may be deduced from their online behavior. Due to a failure of regulation, Internet users have virtually no means to control such surveillance, and it contravenes a host of well-established social norms. -

Web Tracking – a Literature Review on the State of Research

Proceedings of the 51st Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences j 2018 Web Tracking – A Literature Review on the State of Research Tatiana Ermakova Benedict Bender University of Potsdam University of Potsdam [email protected] [email protected] Benjamin Fabian Kerstin Klimek HfT Leipzig University of Potsdam [email protected] [email protected] Abstract (Fabian et al., 2015; Bender et al., 2016). Hence, driven by a variety of enabling techniques (Besson et Web tracking seems to become ubiquitous in online al., 2014; Sanchez-Rola et al., 2016), web tracking has business and leads to increased privacy concerns of become ubiquitous on the Web (Roesner et al., 2012), users. This paper provides an overview over the across websites and even across devices (Brookman et current state of the art of web-tracking research, al., 2017). Besides targeted advertising (Sanchez-Rola aiming to reveal the relevance and methodologies of et al., 2016; Parra-Arnau, 2017), web tracking can be this research area and creates a foundation for future employed for personalization (Sanchez-Rola et al., work. In particular, this study addresses the following 2016; Mayer & Mitchell, 2012; Roesner et al., 2012), research questions: What methods are followed? What advanced web site analytics, social network integration results have been achieved so far? What are potential (Mayer & Mitchell, 2012; Roesner et al., 2012), and future research areas? For these goals, a structured website development (Fourie & Bothma, 2007). literature review based upon an established For online users, especially mature, well-off and methodological framework is conducted. The identified educated individuals, who constitute the most preferred articles are investigated with respect to the applied target group of web tracking (Peacock, 2015), the web research methodologies and the aspects of web tracking practices also imply higher privacy losses tracking they emphasize. -

Getting Your Google Analytics ID to Get a Google Analytics ID, Do the Following: 1

ECinteractivePLUS®: Setting Up Google Analytics™ for Your Site You can use Google Analytics™ to learn how visitors interact with your site. Google Analytics gives you free reports on your site visitors, including their referring sites, search engines, search keywords, time on each page, pages per visit, geographic location, browser versions, and much more. This analysis can help you make informed decisions about your marketing campaigns, increase conversions from guest to loyal customer, and empower you to grow your business online. Google offers a basic set of Analytics services free of charge. For more details and to sign up, see www.google.com/analytics/. To make Google Analytics easy to implement in ECinteractivePLUS®, your Admin site has a Google Analytics ID box in Site Preferences. After you update your Google Analytics tracking code, the ECinteractivePLUS system automatically enters it onto every page of your front-end site so that Google Analytics can track your traffic. Getting Your Google Analytics ID To get a Google Analytics ID, do the following: 1. Go to the Google Analytics sign-up page and log in to your Google account. If you don’t already have a Google account, click Create Account and complete the sign-up process. 2. Complete the Google Analytics sign-up process. When prompted for your site URL, enter your site URL including the directory path that has your ECI DDMS® account number (www.ecinteractive. com/#####). The Google Analytics page displays instructions for adding a script block to each page. In this script block, look for your tracking code that begins with UA- followed by a series of numbers. -

Apache Shindig V

...................................................................................................................................... Apache Shindig v. 1.0 User Guide ...................................................................................................................................... The Apache Software Foundation 2012-03-11 T a b l e o f C o n t e n t s i Table of Contents ....................................................................................................................................... 1. Table of Contents . i 2. Introduction . 1 3. Download . 3 4. Overview . 6 5. Getting Started . 16 6. Documentation Centre . 22 7. Java . 23 8. Building Java . 24 9. Samples . 28 10. PHP . 29 11. Building PHP . 30 12. Features . 32 13. Community Overview . 35 14. Getting Help . 37 15. Code Conventions . 38 16. Jira Conventions . 39 17. SVN Conventions . 40 18. Shindig Release Process . 42 19. FAQ . 46 20. Powered By . 48 21. Resources . 49 © 2 0 1 2 , T h e A p a c h e S o f t w a r e F o u n d a t i o n • A L L R I G H T S R E S E R V E D . T a b l e o f C o n t e n t s ii © 2 0 1 2 , T h e A p a c h e S o f t w a r e F o u n d a t i o n • A L L R I G H T S R E S E R V E D . 1 I n t r o d u c t i o n 1 1 Introduction ....................................................................................................................................... 1.1 Welcome To Apache Shindig ! Apache Shindig is an OpenSocial container and helps you to start hosting OpenSocial apps quickly by providing the code to render gadgets, proxy requests, and handle REST and RPC requests. -

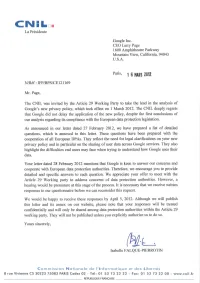

Questionnaire to Google

Questionnaire to Google 1. Definitions The following terms will be used for the purpose of this questionnaire: a) “Google service ”: any service operated by Google that interacts with users and/or their terminal equipment through a network, such as Google Search, Google+, Youtube, Analytics, DoubleClick, +1, Google Location Services and Google Android based software. b) “personal data ”: any information relating to an identified or identifiable natural person, as defined in article 2(a) of Directive 95/46/EC, taking into account the clarifications provided in recital 26 of the same Directive. c) “processing ”: the processing of personal data as defined in article 2(b) of Directive 95/46/EC. d) “Sensitive data ”: any type of data revealing racial or ethnic origin, political opinions, religious or philosophical beliefs, trade-union membership, or data concerning health or sex life, as defined in article 8(1) of Directive 95/46/EC (“special categories of data”). e) “new privacy policy ”: Google’s new privacy policy which took effect on 1 March 2012. f) “non-authenticated user ”: a user accessing a Google service without signing in to a Google account, as opposed to an “authenticated user ”. g) “passive user ”: a user who does not directly request a Google service but from whom data is still collected, typically through third party ad platforms, analytics or +1 buttons. h) “consent ”: any freely given specific and informed indication of the data subjects wishes by which he signifies his agreement to personal data relating to him being processed, as defined in article 2 (h) of Directive 95/46/EC.