Chapter 3. Walking Contradictions: Spatial Practices in Tsing Yi, Hong Kong

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Buildings with Confirmed / Probable Cases of COVID-19

List of Buildings With Confirmed / Probable Cases of COVID-19 List of Residential Buildings in Which Confirmed / Probable Cases Have Resided (Note: The buildings will remain on the list for 14 days since the reported date.) Related Confirmed / District Building Name Probable Case(s) Islands Hong Kong Skycity Marriott Hotel 5482 Islands Hong Kong Skycity Marriott Hotel 5483 Yau Tsim Mong Block 2, The Long Beach 5484 Kwun Tong Dorsett Kwun Tong, Hong Kong 5486 Wan Chai Victoria Heights, 43A Stubbs Road 5487 Islands Tower 3, The Visionary 5488 Sha Tin Yue Chak House, Yue Tin Court 5492 Islands Hong Kong Skycity Marriott Hotel 5496 Tuen Mun King On House, Shan King Estate 5497 Tuen Mun King On House, Shan King Estate 5498 Kowloon City Sik Man House, Ho Man Tin Estate 5499 Wan Chai 168 Tung Lo Wan Road 5500 Sha Tin Block F, Garden Rivera 5501 Sai Kung Clear Water Bay Apartments 5502 Southern Red Hill Park 5503 Sai Kung Po Lam Estate, Po Tai House 5504 Sha Tin Block F, Garden Rivera 5505 Islands Ying Yat House, Yat Tung Estate 5506 Kwun Tong Block 17, Laguna City 5507 Crowne Plaza Hong Kong Kowloon East Sai Kung 5509 Hotel Eastern Tower 2, Pacific Palisades 5510 Kowloon City Billion Court 5511 Yau Tsim Mong Lee Man Building 5512 Central & Western Tai Fat Building 5513 Wan Chai Malibu Garden 5514 Sai Kung Alto Residences 5515 Wan Chai Chee On Building 5516 Sai Kung Block 2, Hillview Court 5517 Tsuen Wan Hoi Pa San Tsuen 5518 Central & Western Flourish Court 5520 1 Related Confirmed / District Building Name Probable Case(s) Wong Tai Sin Fu Tung House, Tung Tau Estate 5521 Yau Tsim Mong Tai Chuen Building, Cosmopolitan Estates 5523 Yau Tsim Mong Yan Hong Building 5524 Sha Tin Block 5, Royal Ascot 5525 Sha Tin Yiu Ping House, Yiu On Estate 5526 Sha Tin Block 5, Royal Ascot 5529 Wan Chai Block E, Beverly Hill 5530 Yau Tsim Mong Tower 1, The Harbourside 5531 Yuen Long Wah Choi House, Tin Wah Estate 5532 Yau Tsim Mong Lee Man Building 5533 Yau Tsim Mong Paradise Square 5534 Kowloon City Tower 3, K. -

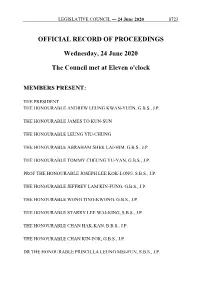

Official Record of Proceedings

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ― 24 June 2020 8723 OFFICIAL RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 24 June 2020 The Council met at Eleven o'clock MEMBERS PRESENT: THE PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE ANDREW LEUNG KWAN-YUEN, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE JAMES TO KUN-SUN THE HONOURABLE LEUNG YIU-CHUNG THE HONOURABLE ABRAHAM SHEK LAI-HIM, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE TOMMY CHEUNG YU-YAN, G.B.S., J.P. PROF THE HONOURABLE JOSEPH LEE KOK-LONG, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE JEFFREY LAM KIN-FUNG, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE WONG TING-KWONG, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE STARRY LEE WAI-KING, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN HAK-KAN, B.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN KIN-POR, G.B.S., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE PRISCILLA LEUNG MEI-FUN, S.B.S., J.P. 8724 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ― 24 June 2020 THE HONOURABLE WONG KWOK-KIN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS REGINA IP LAU SUK-YEE, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE PAUL TSE WAI-CHUN, J.P. THE HONOURABLE CLAUDIA MO THE HONOURABLE MICHAEL TIEN PUK-SUN, B.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE STEVEN HO CHUN-YIN, B.B.S. THE HONOURABLE FRANKIE YICK CHI-MING, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE WU CHI-WAI, M.H. THE HONOURABLE YIU SI-WING, B.B.S. THE HONOURABLE MA FUNG-KWOK, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHARLES PETER MOK, J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN CHI-CHUEN THE HONOURABLE CHAN HAN-PAN, B.B.S., J.P. -

偉順旅運服務有限公司wai Shun Travel Services

偉順旅運服務有限公司 Wai Shun Travel Services Ltd 學之園幼稚園暨雙語幼兒園(星匯校*) – 2020-2021年度褓姆車路線圖 Learning Habitat Kindergarten & Bilingual Nursery (The Sparkle Campus*) Nanny Bus Route for School Year 2020-2021 雙程 單程 地區 建議路線 (HK$) (HK$) 荔枝角 泓景臺,昇悅居,一號西九龍 Lai Chi Kok Banyan Garden, Liberte, One West Kowloon 750 500 美孚 美孚新邨,曼克頓山,美孚西港鐵站 Mei Foo Mei Foo Sun Chuen, Manhattan Hill, Mei Foo MTR Station 770 520 荔景(荔景山路) 荔欣苑,華荔邨,盈暉臺,清麗苑,鐘山台 Lai King (Lai King Hill Road) Lai Yan Court, Wah Lai Estate, Nob Hill, Ching Lai Court, Chung Shan Terrace 950 640 荔景 紀律部隊宿舍,浩景臺,祖堯邨 Lai King Disciplined Services Quarters, Highland Park, Cho Yiu Chuen 1150 770 荃灣 翠濤閣,灣景花園,麗城花園,韻濤居,翠豐臺,綠楊新邨 Greenview Court, Bayview Garden, Belvedere Garden, Serenade Cove, Summit (青山公路段) 1330 890 Terrace, Luk Yeung Sun Chuen, 荃灣 荃灣西港鐵站,萬景峰,環宇海灣,海濱花園 Tsuen Wan Tsuen Wan West,Vision City, City Point, Riviera Gardens 1280 860 青衣 灝景灣,翠怡花園,藍澄灣, 盈翠半島,宏福花園 Tsing Yi Villa Esplanada, Tivoli Garden, Rambler Crest, Tierra Verde, Tierra Verde 1200 800 長沙灣 喜盈, 喜薈 Cheung Sha Wan Heya Delight, Heya Crystal 900 600 大角咀及奧運 維港灣,浪澄灣, 君匯港 ,港灣豪庭 Tai Kok Tsui, Olympic Station Island Harbourview, The Long Beach, Harbour Green, Metro Harbour View 950 640 深水埗及南昌 怡靖苑,喜雅,麗安邨, 匯壐 Sham Shui Po, Nam Cheong Yee Ching Court, Heya Green, Lai On Estate, Cullinan West 950 640 九龍站,柯士甸及佐敦 擎天半島,漾日居,港景峰 West Kowloon, Austin, Jordan Sorrento,The Waterfront, The Victoria Towers 1100 740 太子,油麻地 富榮花園,柏景灣,界限街 (太子),大埔道 (深水埗) Charming Garden, Park Avenue, Boundary Street (prince Edward),Tai Po Road (Sham Prince Edward, Yan Ma Tei 1100 740 Shui Po) 九龍塘 九龍塘港鐵站,窩打老道(九龍塘) Kowloon Tong Kowloon Tong MTR Station, Waterloo Road (Kowloon Tong) 1280 860 旺角,何文田 佛光街,龍騰閣,窩打老道(旺角) Mong Kok, Ho Man Tin Fat Kwong Street, Lung Tang Court, Waterloo Road (Mong Kok) 1350 900 深井 碧堤半島,海韻花園,麗都花園 Sham Tseng Bellagio, Rhine Garden, Lido Garden 1450 970 紅磡 海逸豪園,黃埔花園,海濱南岸 Hung Hom Laguna Verde, Whampoa Garden, Harbour Place 1450 970 備註Remarks: 1.) 上述資料只供家長參考,有關褓姆車收費詳情將於稍後通知。 The information above is for reference. -

OFFICIAL RECORD of PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 11

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ― 11 July 2018 14157 OFFICIAL RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 11 July 2018 The Council met at Eleven o'clock MEMBERS PRESENT: THE PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE ANDREW LEUNG KWAN-YUEN, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE JAMES TO KUN-SUN THE HONOURABLE LEUNG YIU-CHUNG THE HONOURABLE TOMMY CHEUNG YU-YAN, G.B.S., J.P. PROF THE HONOURABLE JOSEPH LEE KOK-LONG, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE JEFFREY LAM KIN-FUNG, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE WONG TING-KWONG, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE STARRY LEE WAI-KING, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN HAK-KAN, B.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN KIN-POR, G.B.S., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE PRISCILLA LEUNG MEI-FUN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE WONG KWOK-KIN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS REGINA IP LAU SUK-YEE, G.B.S., J.P. 14158 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ― 11 July 2018 THE HONOURABLE PAUL TSE WAI-CHUN, J.P. THE HONOURABLE CLAUDIA MO THE HONOURABLE MICHAEL TIEN PUK-SUN, B.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE STEVEN HO CHUN-YIN, B.B.S. THE HONOURABLE FRANKIE YICK CHI-MING, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE WU CHI-WAI, M.H. THE HONOURABLE YIU SI-WING, B.B.S. THE HONOURABLE MA FUNG-KWOK, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHARLES PETER MOK, J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN CHI-CHUEN THE HONOURABLE CHAN HAN-PAN, B.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEUNG CHE-CHEUNG, S.B.S., M.H., J.P. -

M / SP / 14 / 173 Ser Res

¬½á W¤á 300 200 Sheung Fa Shan LIN FA SHAN Catchwater flW˘§⁄ł§¤‚˛†p›ˇ M / SP / 14 / 173 Ser Res 200 w 200 SEE PLAN REF. No. M / SP / 14 / 173 NEEDLE HILL 532 FOR TSUEN WAN VILLAGE CLUSTER BOUNDARIES 500 è¦K 45 Catchwater fih 400 Catchwater 400 2 _ij 100 flW˘§⁄ł§¤‚˛†p›ˇ M / SP / 14 / 172 The Cliveden The Cairnhill JUBILEE (SHING MUN) ROUTE RESERVOIR ê¶È¥ Catchwater «ø 314 Yuen Yuen 9 SEE PLAN REF. No. M / SP / 14 / 172 Institute M' y TWISK Wo Yi Hop 46 23 22 10 FOR TSUEN WAN VILLAGE CLUSTER BOUNDARIES Ser Res 11 SHING MUN ROAD 200 Catchwater 300 Ser Res 3.2.1 Á³z² GD„‹ HILLTOP ROAD ãÅF r ú¥OªÐ e flA Toll Gate t 474 a Kwong Pan Tin 12 w h San Tsuen D c ù t «ø“G a C ¥s 25 SHEK LUNG KUNG ƒ Po Kwong Yuen –‰ ú¥Oª LO WAI ROAD ¶´ú 5 Tso Kung Tam Kwong Pan Tin «ø Tsuen “T Fu Yung Shan ƒ SAMT¤¯· TUNG UK ROAD 5 Lo Wai 14 20 Sam Tung Uk fl” 22 ø–⁄ U¤á 315 24 Resite Village 300 Ha Fa Shan ROAD ¥—¥ H¶»H¶s s· CHUN Pak Tin Pa 8 Cheung Shan 100 fl” 19 San Tsuen YI PEI 400 fl´« TSUEN KING CIRCUIT San Tsuen 13 Estate 100 5 ROAD Allway Gardens flW˘ 100 3.2.2 fl”· SHAN 3 ROAD fi Tsuen Wan Centre FU YUNG SHING 25 ˦Lª MUN Ser Res 28 Chuk Lam Hoi Pa Resite Village ST Tsuen King Sim Yuen 252 ¤{ ON YIN Garden G¤@ G¤@« Ma Sim Pei Tsuen Łƒ… “T» Yi Pei Chun Lei Muk Shue 2 SHING MUN TUNNEL »» 26 Sai Lau Kok Ser Res Ser Res CHEUNG PEI SHAN ROAD Estate w ¥—¥ Tsuen Heung Fan Liu fl MEI WAN STREET 21 Pak Tin Pa M©y© ROAD «ø“ ·wƒ Tsuen 12 MA SIM PAI Lower Shing Mun Ser Res 18 Village «ø“ flw… 7 TSUEN KING CIRCUIT A ⁄· fi¯ł «ø“ƒ¤ Tsuen Tak ¤{ 200 ½ Shing Mun Valley W¤ª Garden -

List of Buildings with Confirmed / Probable Cases of COVID-19

List of Buildings With Confirmed / Probable Cases of COVID-19 List of Residential Buildings in Which Confirmed / Probable Cases Have Resided (Note: The buildings will remain on the list for 14 days since the reported date.) Related Confirmed / District Building Name Probable Case(s) Wan Chai Block C, Fontana Garden 5868 Yau Tsim Mong Cam Key Mansion, 495 Shanghai Street 5869 Kowloon City Crystal Mansion 5870 Central & Western Best Western Plus Hotel Hong Kong 5871 Central & Western Tower 1, Kong Chian Tower 5872 Wan Chai 11 Broom Road 5873 Kwai Tsing Wah Shun Court 5874 Kowloon City Sunderland Estate 5875 Islands Headland Hotel 5877 Eastern Block A, Yen Lok Building 5879 Sha Tin Hin Kwai House, Hin Keng Estate 5880 Tai Po Po Sam Pai Village 5881 Sha Tin Mei Chi House, Mei Tin Estate 5882 Tsuen Wan Block 2, Waterside Plaza 5882 Sha Tin Jubilee Court, Jubilee Garden 5883 Kwun Tong Lee Ming House, Shun Lee Estate 5884 Southern Tower 9, Bel-Air On The Peak 5885 Central & Western Block 3, Garden Terrace 5886 Sai Kung Tower 5, The Mediterranean 5887 Sai Kung Tower 5, The Mediterranean 5888 Kowloon City Block 1, Kiu Wang Mansion 5889 Islands Heung Yat House, Yat Tung Estate 5890 Sha Tin Cypress House, Kwong Yuen Estate 5891 Kwai Tsing Block 6, Mayfair Gardens 5892 Eastern Tower 1, Harbour Glory 5893 Sai Kung Kap Pin Long 5894 Wan Chai Hawthorn Garden 5895 Tai Po Villa Castell 5896 Kwun Tong Ping Shun House, Ping Tin Estate 5897 Sai Kung Tak Fu House, Hau Tak Estate 5898 Kwai Tsing Ying Kwai House, Kwai Chung Estate 5899 1 Related Confirmed / -

Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17

WWF - DDC Location Plan May-2018 Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun 1 2 3 4 5 6 Team A Day-Off Tsuen Wan Plaza Diamond Hill MTR Exit A2 Lau Sin Street, Tin Hau King Man Street, Sai Kung (Near Sai Kung Library) Day-Off Hang Seng Bank Head Office, Central New Jade Shopping Centre, Chai Wan New Jade Shopping Centre, Chai Wan Team B Shatin Plaza Shatin Plaza Shatin Plaza (Near Footbridge) (Near Footbridge) (Near Footbridge) Hang Seng Bank Head Office, Central New Jade Shopping Centre, Chai Wan Team C Canal Road East Bridge, Causeway Bay Hong Kong MTR Station Yuen Long MTR Station Yuen Long MTR Station (Near Footbridge) (Near Footbridge) Hang Seng Bank Head Office, Central Team D Wu Kai Sha MTR Station Exit B Canal Road East Bridge, Causeway Bay Yuen Long MTR Station Tsuen Wan Plaza (Near Footbridge) Tsuen Wan Plaza (Near Footbridge) (Near Footbridge) World Wide House, Central World Wide House, Central Team E Tuen Mun MTR Station Wu Kai Sha MTR Station Exit B Canal Road East Bridge, Causeway Bay Tsuen Wan Plaza (Near Footbridge) (Near Footbridge) (Near Footbridge) World Wide House, Central Team F Causeway Bay Plaza 1 (Near Footbridge) Tuen Mun MTR Station Wu Kai Sha MTR Station Exit B Chai Wan MTR Station Chai Wan MTR Station (Near Footbridge) Team G Admiralty MTR Station Exit A Causeway Bay Plaza 1 (Near Footbridge) Tuen Mun MTR Station Chai Wan MTR Station Austin MTR Station Exit B (Near Footbridge) Austin MTR Station Exit B (Near Footbridge) Team H Tai Wai MTR Station Exit D Admiralty MTR Station Exit A Causeway Bay Plaza 1 (Near Footbridge) Austin -

Register of Public Payphone

Register of Public Payphone Operator Kiosk ID Street Locality District Region HGC HCL-0007 Chater Road Outside Statue Square Central and HK Western HGC HCL-0010 Chater Road Outside Statue Square Central and HK Western HGC HCL-0024 Des Voeux Road Central Outside Wheelock House Central and HK Western HKT HKT-2338 Caine Road Outside Albron Court Central and HK Western HKT HKT-1488 Caine Road Outside Ho Shing House, near Central - Mid-Levels Central and HK Escalators Western HKT HKT-1052 Caine Road Outside Long Mansion Central and HK Western HKT HKT-1090 Charter Garden Near Court of Final Appeal Central and HK Western HKT HKT-1042 Chater Road Outside St George's Building, near Exit F, MTR's Central Central and HK Station Western HKT HKT-1031 Chater Road Outside Statue Square Central and HK Western HKT HKT-1076 Chater Road Outside Statue Square Central and HK Western HKT HKT-1050 Chater Road Outside Statue Square, near Bus Stop Central and HK Western HKT HKT-1062 Chater Road Outside Statue Square, near Court of Final Appeal Central and HK Western HKT HKT-1072 Chater Road Outside Statue Square, near Court of Final Appeal Central and HK Western HKT HKT-2321 Chater Road Outside Statue Square, near Prince's Building Central and HK Western HKT HKT-2322 Chater Road Outside Statue Square, near Prince's Building Central and HK Western HKT HKT-2323 Chater Road Outside Statue Square, near Prince's Building Central and HK Western HKT HKT-2337 Conduit Road Outside Elegant Garden Central and HK Western HKT HKT-1914 Connaught Road Central Outside Shun Tak -

DDC Location Plan Nov-2016

WWF - DDC Location Plan Nov-2016 Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun 1 2 3 4 5 6 Ma Tau Wai Road Nam Ning Street, Aberdeen Wu Kai Sha MTR Station Team A Fanling MTR Station Sai Wan Ho MTR Exit B Training / Day Off (near HSBC) (near Aberdeen Centre) Exit B Yun Ping Road, Causeway Bay (Near Team B Sai Ying Pun MTR Exit C Ngau Tau Kok MTR Exit A Fanling MTR Station Stanley Main Street Training / Day Off Hang Seng Bank) Yuen Lung Street, Yuen Long (near Yoho Yuen Lung Street, Yuen Long Yuen Lung Street, Yuen Long Queen's Road Central Queen's Road,Central Queen's Road Central Team C Town) (near Yoho Town) (near Yoho Town) (near Cosco Tower) (near Cosco Tower) (near Cosco Tower) Prince Edward Road East Prince Edward Road East Prince Edward Road East Siu Sai Wan Road, Chai Wan Siu Sai Wan Road, Chai Wan Siu Sai Wan Road, Chai Wan Team D (near Mikki Mall) (near Mikki Mall) (near Mikki Mall) (near Siu Sai Wan Complex) (near Siu Sai Wan Complex) (near Siu Sai Wan Complex) Kai Tin Road, Lam Tin Kai Tin Road, Lam Tin Kai Tin Road, Lam Tin Team E Tuen Mun MTR Station Tuen Mun MTR Station Tuen Mun MTR Station (near Kai Tin Shopping Centre) (near Kai Tin Shopping Centre) (near Kai Tin Shopping Centre) 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Cheung Sha Wan Road, Lai Chi Kok Tuen Mun Lung Mun Road Team A Luen Wo Hui, Fanling Fo Tan MTR Station Hang Hau MTR Exit A Kennedy Town MTR Exit C Training / Day Off (near Cheung Sha Wan Plaza) (near Lung Mun Oasis) Nam Ning Street, Aberdeen Tong Tak Street, Tseung Kwan O Tai Wo Road, Tai Wo Chan Man Street, Sai Kung Team B Man Siu Street, Hung -

M / SP / 14 / 172 San Tsuen �¥S SHEK LUNG KUNG �–‰ Ú¥Oª SEE PLAN REF

200 451 è¦K Catchwater 400 303 fih 100 The Cairnhill 100 ROUTE 314 TWISK 80 200 Ser Res 80 100 Catchwater Ser Res TAI LAM CHUNG RESERVOIR ú¥OªÐ 474 flA Kwong Pan Tin flW˘§⁄ł§¤‚˛†p›ˇ M / SP / 14 / 172 San Tsuen ¥s SHEK LUNG KUNG –‰ ú¥Oª SEE PLAN REF. No. M / SP / 14 / 172 Tso Kung Tam Kwong Pan Tin Tsuen “T FOR TSUEN WAN VILLAGE CLUSTER BOUNDARIES Fu Yung Shan fl” U¤á 315 80 j¤VÆ 300 Ha Fa Shan ¥—¥ flW˘ fl´« Pak Tin Pa TSUEN KING CIRCUIT San Tsuen 400 Allway Gardens 100 100 Tsuen Wan Centre fl”· 200 Tsuen King Garden ¤{ Ma Sim Pei Tsuen “T» ¥—¥ Pak Tin Pa fl Tsuen ·wƒ TSUEN KING CIRCUIT Adventist Hospital flw… A A ⁄· Tsuen Tak Garden Kam Fung r´º´s ½ Muk Min Ha Tsuen 200 259 Garden 200 Discovery Park ROUTE TWISK 300 A» 200 Summit C«s⁄‰⁄‚ CASTLE Terrace ã®W PEAK ROAD - TSUEN WAN CHAI WAN KOK _ b¥s D e NORTH Pun Shan Tsuen j ROAD HO ã®WÆ TAI C«fi Catchwater TSUEN WAN F¨L fi WAN ” fl CHAI WAN KOK STREET Fuk Loi Estate ñº¨· Tsuen Wan LineLuk Yeung 226 Catchwater HOI PA STREET Sun Chuen 3.3.5 TAI CHUNG ROAD TUEN MUN ROAD ¡º 200 SHA TSUI ROAD j¤ 300 oªa¬ Yau Kom Tau HOI SHING ROAD ½ CASTLE PEAK ROAD - TSUEN j¤e Village R˜« 8 HOI HING ROAD j¤VÆk¤ Ser Res ù Belvedere Garden flW Tai Lam Centre SAI LAU KOK j¤VÆg Ser Res for Women 100 flW˘ C Tai Lam Correctional 344 3.3.4 j¤F Institution M†§ s TAI HO ROAD ½ Tsing Fai Tong o“a‹Y New Village 1 fi‡ SHAM TSENG Yau Kom Tau ROAD flW˘ t¤s TSUEN WAN ê¶ `² w SETTLEMENT Treatment Works fl fi– Tsuen Wan HOI ON ROAD Yuen Tun Catchwater BASIN SHAM TSENG RÄ£³ A» Plaza W ³²w w… Lindo Green Greenview Court TSUEN WAN è¬w¼L MARKET -

Name of Buildings Awarded the Quality Water Supply Scheme for Buildings – Fresh Water (Plus) Certificate (As at 8 February 2018)

Name of Buildings awarded the Quality Water Supply Scheme for Buildings – Fresh Water (Plus) Certificate (as at 8 February 2018) Name of Building Type of Building District @Convoy Commercial/Industrial/Public Utilities Eastern 1 & 3 Ede Road Private/HOS Residential Kowloon City 1 Duddell Street Commercial/Industrial/Public Utilities Central & Western 100 QRC Commercial/Industrial/Public Utilities Central & Western 102 Austin Road Commercial/Industrial/Public Utilities Yau Tsim Mong 1063 King's Road Private/HOS Residential Eastern 11 MacDonnell Road Private/HOS Residential Central & Western 111 Lee Nam Road Commercial/Industrial/Public Utilities Southern 12 Shouson Hill Road Private/HOS Residential Central & Western 127 Repulse Bay Road Private/HOS Residential Southern 12W Commercial/Industrial/Public Utilities Tai Po 15 Homantin Hill Private/HOS Residential Yau Tsim Mong 15W Commercial/Industrial/Public Utilities Tai Po 168 Queen's Road Central Commercial/Industrial/Public Utilities Central & Western 16W Commercial/Industrial/Public Utilities Tai Po 17-19 Ashley Road Commercial/Industrial/Public Utilities Yau Tsim Mong 18 Farm Road (Shopping Arcade) Commercial/Industrial/Public Utilities Kowloon City 18 Upper East Private/HOS Residential Eastern 1881 Heritage Commercial/Industrial/Public Utilities Yau Tsim Mong 211 Johnston Road Commercial/Industrial/Public Utilities Wan Chai 225 Nathan Road Commercial/Industrial/Public Utilities Yau Tsim Mong Name of Buildings awarded the Quality Water Supply Scheme for Buildings – Fresh Water (Plus) -

Driving Services Section

DRIVING SERVICES SECTION Taxi Written Test - Part B (Location Question Booklet) Note: This pamphlet is for reference only and has no legal authority. The Driving Services Section of Transport Department may amend any part of its contents at any time as required without giving any notice. Location (Que stion) Place (Answer) Location (Question) Place (Answer) 1. Aberdeen Centre Nam Ning Street 19. Dah Sing Financial Wan Chai Centre 2. Allied Kajima Building Wan Chai 20. Duke of Windsor Social Wan Chai Service Building 3. Argyle Centre Nathan Road 21. East Ocean Centre Tsim Sha Tsui 4. Houston Centre Mody Road 22. Eastern Harbour Centre Quarry Bay 5. Cable TV Tower Tsuen Wan 23. Energy Plaza Tsim Sha Tsui 6. Caroline Centre Ca useway Bay 24. Entertainment Building Central 7. C.C. Wu Building Wan Chai 25. Eton Tower Causeway Bay 8. Central Building Pedder Street 26. Fo Tan Railway House Lok King Street 9. Cheung Kong Center Central 27. Fortress Tower King's Road 10. China Hong Kong City Tsim Sha Tsui 28. Ginza Square Yau Ma Tei 11. China Overseas Wan Chai 29. Grand Millennium Plaza Sheung Wan Building 12. Chinachem Exchange Quarry Bay 30. Hilton Plaza Sha Tin Square 13. Chow Tai Fook Centre Mong Kok 31. HKPC Buil ding Kowloon Tong 14. Prince ’s Building Chater Road 32. i Square Tsim Sha Tsui 15. Clothing Industry Lai King Hill Road 33. Kowloonbay Trademart Drive Training Authority Lai International Trade & King Training Centre Exhibition Centre 16. CNT Tower Wan Chai 34. Hong Kong Plaza Sai Wan 17. Concordia Plaza Tsim Sha Tsui 35.