"Folk" Theatre* APARNA DHARWADKER

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Volume 1 on Stage/ Off Stage

lives of the women Volume 1 On Stage/ Off Stage Edited by Jerry Pinto Sophia Institute of Social Communications Media Supported by the Laura and Luigi Dallapiccola Foundation Published by the Sophia Institute of Social Communications Media, Sophia Shree B K Somani Memorial Polytechnic, Bhulabhai Desai Road, Mumbai 400 026 All rights reserved Designed by Rohan Gupta be.net/rohangupta Printed by Aniruddh Arts, Mumbai Contents Preface i Acknowledgments iii Shanta Gokhale 1 Nadira Babbar 39 Jhelum Paranjape 67 Dolly Thakore 91 Preface We’ve heard it said that a woman’s work is never done. What they do not say is that women’s lives are also largely unrecorded. Women, and the work they do, slip through memory’s net leaving large gaps in our collective consciousness about challenges faced and mastered, discoveries made and celebrated, collaborations forged and valued. Combating this pervasive amnesia is not an easy task. This book is a beginning in another direction, an attempt to try and construct the professional lives of four of Mumbai’s women (where the discussion has ventured into the personal lives of these women, it has only been in relation to the professional or to their public images). And who better to attempt this construction than young people on the verge of building their own professional lives? In learning about the lives of inspiring professionals, we hoped our students would learn about navigating a world they were about to enter and also perhaps have an opportunity to reflect a little and learn about themselves. So four groups of students of the post-graduate diploma in Social Communications Media, SCMSophia’s class of 2014 set out to choose the women whose lives they wanted to follow and then went out to create stereoscopic views of them. -

Prospectus 2017-18

PROSPECTUS 2017 National School of Drama (an Autonomous institution of the Ministry of Culture, Govt. of India) Sikkim Theatre Training Centre Nepali Sahitya Parishad Bhawan Development Area Gangtok, Sikkim 737101 NATIONAL SCHOOL OF DRAMA Ph - 03592 201010 [email protected] http://sikkim.nsd.gov.in SIKKIM THEATRE TRAINING CENTRE 2 NSD 4 Former Chairpersons Directors & 6 NSD Chairman 7 NSD Director 9 Centre Incharge 10 NSD, STTC 11 Camp Director 12 Vision & Objectives 13 Subject of study 14 Syllabus 16 Epigrammatic Report From April 2016 to March 2017 20 List of Visiting Faculty 22 Admission Related Matters 24 General Information 26 Centre Festivals 28 Administrative & Technical Staff 30 Repertory Company 32 How to reach 2 NSD 4 Former Chairpersons Directors & 6 NSD Chairman 7 NSD Director 9 Centre Incharge 10 NSD, STTC 11 Camp Director 12 Vision & Objectives 13 Subject of study 14 Syllabus 16 Epigrammatic Report From April 2016 to March 2017 20 List of Visiting Faculty 22 Admission Related Matters 24 General Information 26 Centre Festivals 28 Administrative & Technical Staff 30 Repertory Company 32 How to reach NATIONAL SCHOOL OF DRAMA NEW DELHI The National School of Drama is one of the foremost theatre training institutions in the world and the only one of its kind in India. Established in 1959 as a constituent unit of the Sangeet Natak Akademi, the School became an independent entity in 1975 and was registered as an autonomous organization under the Societies Registration Act XXI of 1860, fully financed by the Ministry of Culture, Government of India. The School offers an intensive and comprehensive three-year course of training in theatre and the allied arts. -

Foojf.Kdk ROSPECTUS Ear Residentialcer Course Indramaticar Tificate

ROSPECTUS NSD SIKKIM one year residential certificate foojf.kdkcourse in dramatic arts 2020 NSD SIKKIMGovt. of Sikkim has allotted a piece of land to National School of Drama, Sikkim in 2019 to establish its own permanent infrastructure at Assam Lingzey Forest Block, near Gangtok. Front cover photo: Letter of allotment of the land Kalidasa’s Abhijnan Shakuntalam, Official Map of the land Dir. Piyal Bhattacharya, (Student’s Production, 2019) Way to Saurani Phatak Land of Social Justice & Welfare Dept. Private Holding ICDS Centre Private Holding Govt. of Sikkim Land position in Private Holding the Google Map Kanchanjangha Peak Contents 3 National School of Drama, New Delhi 4 Former Chairpersons & Directors of NSD 5 National School of Drama, Sikkim 6 The Chairman, NSD Society 7 The Director, NSD 8 The Centre In-charge, NSD 9 The Centre Director, NSD Sikkim 11 The Vision & Objectives of NSD, Sikkim 12 Subjects of Study 14 Syllabus 16 Annual Activity Report 18 Visiting Faculty Members 19 Admission Related Matters 22 General Information 24 NSD Sikkim Repertory Company 26 Administrative & Technical Staff 28 Theatre Festivals Location & Travel Route English C3 Hami Nai Aafai Aaf, a dramatisation of Padma Sachdev’s Dogri Novel Ab Na Banegi Dehri, Dir. Bipin Kumar (Students/Repertory Production, 2011/12) National School of Drama ational School of Drama is one of the foremost theatre training institutions in the world and the Nonly one of its kind in India. Established in 1959 as a constituent unit of the Sangeet Natak Akademi, the School became an independent entity in 1975 and was registered as an autonomous organization under Societies Registration Act XXI of 1860, fully financed by the Ministry of Culture, Government of India. -

A Theatre of Their Own: Indian Women Playwrights in Perspective

A THEATRE OF THEIR OWN: INDIAN WOMEN PLAYWRIGHTS IN PERSPECTIVE A Thesis submitted to the University of North Bengal For the Award of Doctor of Philosophy in English By PINAKI RANJAN DAS Assistant Professor of English Nehru College, Bahadurganj Under the supervision of Dr. ASHIS SENGUPTA Professor Department of English University of North Bengal Department of English University of North Bengal December, 2019 ii iii iv v Abstract In an age where academic curriculum has essentially pushed theatre studies into 'post- script', and the cultural 'space' of making and watching theatre has been largely usurped by the immense popularity of television and 'mainstream' cinemas, it is important to understand why theatre still remains a 'space' to be reckoned as one's 'own'. And to argue for a 'theatre' of 'their own' for the Indian women playwrights (and directors), it is important to explore the possibilities that modern Indian theatre can provide as an instrument of subjective as well as social/ political/ cultural articulations and at the same time analyse the course of Indian theatre which gradually underwent broadening of thematic and dramaturgic scope in order to accommodate the independent voices of the women playwrights and directors. When women playwrights and directors are brought into 'perspective', the social politics concerning women loom large. Though we come across women playwrights like Swarna Kumari Devi, Anurupa Devi or Bimala Sundari Devi in the pre-independence colonial period, it is only from the 1970s onwards that we find a significant population of Indian women playwrights and directors regularly participating in the process of 'theatre making'. -

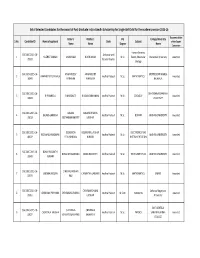

PG IG SGC-2015-16-Website Selection.Xlsx

list of Selected Candidates for the award of Post Graduate Indira Gandhi Scholarship for Single Girl Child for the academic session 2015-16 Father's Mother's PG College/University Recommedation S.No. Candidate ID Name of applicant State Subject of the Expert Name Name Degree Name Committee Human Genetics SGC-OBC-2015-16- Andaman and 1 NUZHAT UMRAN UMRAN ALI NOOR JAHAN M.Sc. & Molecular Bharathiar University Awarded 39593 Nicobar Islands Biology SGC-GEN-2015-16- ANAPAREDDY ANAPAREDDY MONTESSORI MAHILA 2 ANAPAREDDY SYAMALA Andhra Pradesh M.Sc. MATHEMATICS Awarded 30849 RATHAIAH AKKAMMA KALASALA SGC-OBC-2015-16- SRI KRISHNADEVARAYA 3 B PRAMEELA B MADDILETI B ADILAKSHMAMMA Andhra Pradesh M.Sc. ZOOLOGY Awarded 34803 UNIVERSITY SGC-OBC-2015-16- BALAKA BALAKA BHAGYA 4 BALAKA SARANYA Andhra Pradesh M.Sc. BOTANY ANDHRA UNIVERSITY Awarded 35010 SEETHARAMAMURTY LAKSHMI SGC-OBC-2015-16- BEZAWADA BEZAWADA LAKSHMI ELECTRONICS AND 5 BEZAWADA MADHAVI Andhra Pradesh M.Sc. ANDHRA UNIVERSITY Awarded 40632 YEDUKONDALU KUMARI INSTRUMENTATION SGC-OBC-2015-16- BONU PRASANTHI 6 BONU APPALANAIDU BONU PARVATHI Andhra Pradesh M.Sc. TECH GEOPHYSICS ANDHRA UNIVERSITY Awarded 35949 KUMARI SGC-OBC-2015-16- C MURALI MOHAN 7 CHENNA MOUNA C ANANTHA LAKSHMI Andhra Pradesh M.Sc. MATHEMATICS SPMVV Awarded 31979 RAO SGC-OBC-2015-16- CHENNAM DHANA Acharya Nagarjuna 8 CHENNAM PRIYANKA CHENNAM SURIBABU Andhra Pradesh M.Com. commerce Awarded 31461 LAKSHMI University SMT.GENTELA SGC-OBC-2015-16- CHEVIRALA CHEVIRALA 9 CHEVIRALA ANUSHA Andhra Pradesh M.Sc. PHYSICS SAKUNTALAMMA Awarded 32027 VENKATESWARARAO KALAVATHI COLLEGE Chaitanya SGC-OBC-2015-16- CHIRUMALLA 10 CHIRUMALLA HARITHA SAROJANA Andhra Pradesh M.Sc. -

Alphabetical List of Recommendations Received for Padma Awards - 2014

Alphabetical List of recommendations received for Padma Awards - 2014 Sl. No. Name Recommending Authority 1. Shri Manoj Tibrewal Aakash Shri Sriprakash Jaiswal, Minister of Coal, Govt. of India. 2. Dr. (Smt.) Durga Pathak Aarti 1.Dr. Raman Singh, Chief Minister, Govt. of Chhattisgarh. 2.Shri Madhusudan Yadav, MP, Lok Sabha. 3.Shri Motilal Vora, MP, Rajya Sabha. 4.Shri Nand Kumar Saay, MP, Rajya Sabha. 5.Shri Nirmal Kumar Richhariya, Raipur, Chhattisgarh. 6.Shri N.K. Richarya, Chhattisgarh. 3. Dr. Naheed Abidi Dr. Karan Singh, MP, Rajya Sabha & Padma Vibhushan awardee. 4. Dr. Thomas Abraham Shri Inder Singh, Chairman, Global Organization of People Indian Origin, USA. 5. Dr. Yash Pal Abrol Prof. M.S. Swaminathan, Padma Vibhushan awardee. 6. Shri S.K. Acharigi Self 7. Dr. Subrat Kumar Acharya Padma Award Committee. 8. Shri Achintya Kumar Acharya Self 9. Dr. Hariram Acharya Government of Rajasthan. 10. Guru Shashadhar Acharya Ministry of Culture, Govt. of India. 11. Shri Somnath Adhikary Self 12. Dr. Sunkara Venkata Adinarayana Rao Shri Ganta Srinivasa Rao, Minister for Infrastructure & Investments, Ports, Airporst & Natural Gas, Govt. of Andhra Pradesh. 13. Prof. S.H. Advani Dr. S.K. Rana, Consultant Cardiologist & Physician, Kolkata. 14. Shri Vikas Agarwal Self 15. Prof. Amar Agarwal Shri M. Anandan, MP, Lok Sabha. 16. Shri Apoorv Agarwal 1.Shri Praveen Singh Aron, MP, Lok Sabha. 2.Dr. Arun Kumar Saxena, MLA, Uttar Pradesh. 17. Shri Uttam Prakash Agarwal Dr. Deepak K. Tempe, Dean, Maulana Azad Medical College. 18. Dr. Shekhar Agarwal 1.Dr. Ashok Kumar Walia, Minister of Health & Family Welfare, Higher Education & TTE, Skill Mission/Labour, Irrigation & Floods Control, Govt. -

Issn 2454-859 Issn 2454-8596

ISSN 2454-8596 www.vidhyayanaejournal.org An International Multidisciplinary Research e-Journal HISTROY OF GUJRATI DRAMA (NATAK) Dr. jignesh Upadhyay Government arts and commerce college, Gadhada (Swamina), Botad. Volume.1 Issue 1 August 2015 Page 1 ISSN 2454-8596 www.vidhyayanaejournal.org An International Multidisciplinary Research e-Journal HISTROY OF GUJRATI DRAMA (NATAK) The region of Gujarat has a long tradition of folk-theatre, Bhavai, which originated in the 14th-century. Thereafter, in early 16th century, a new element was introduced by Portuguese missionaries, who performed Yesu Mashiha Ka Tamasha, based on the life of Jesus Christ, using the Tamasha folk tradition of Maharashtra, which they imbibed during their work in Goa or Maharashtra.[1] Sanskrit drama was performed in temple and royal courts and temples of Gujarat, it didn't influence the local theatre tradition for the masses. The era of British Raj saw British officials inviting foreign operas and theatre groups to entertain them, this in turn inspired local Parsis to start their own travelling theatre groups, largely performed in Gujarati.[2] The first play published in Gujarati was Laxmi by Dalpatram in 1850, it was inspired by ancient Greek comedy Plutus by Aristophanes.[3] In the year 1852, a Parsi theatre group had performed a Shakespearean play in Gujarati language in the city of Surat. In 1853, Parsee Natak Mandali the first theatre group of Gujarati theatre was founded by Framjee Gustadjee Dalal, which staged the first Parsi-Gujarati play,Rustam Sohrab based on the tale of Rostam and Sohrab part of the 10th-century Persian epicShahnameh by Ferdowsi on 29 October 1853, at at the Grant Road Theatre in Mumbai, this marked the begin of Gujarati theatre. -

Department of Comparative Indian Language and Literature (CILL) CSR

Department of Comparative Indian Language and Literature (CILL) CSR 1. Title and Commencement: 1.1 These Regulations shall be called THE REGULATIONS FOR SEMESTERISED M.A. in Comparative Indian Language and Literature Post- Graduate Programme (CHOICE BASED CREDIT SYSTEM) 2018, UNIVERSITY OF CALCUTTA. 1.2 These Regulations shall come into force with effect from the academic session 2018-2019. 2. Duration of the Programme: The 2-year M.A. programme shall be for a minimum duration of Four (04) consecutive semesters of six months each/ i.e., two (2) years and will start ordinarily in the month of July of each year. 3. Applicability of the New Regulations: These new regulations shall be applicable to: a) The students taking admission to the M.A. Course in the academic session 2018-19 b) The students admitted in earlier sessions but did not enrol for M.A. Part I Examinations up to 2018 c) The students admitted in earlier sessions and enrolled for Part I Examinations but did not appear in Part I Examinations up to 2018. d) The students admitted in earlier sessions and appeared in M.A. Part I Examinations in 2018 or earlier shall continue to be guided by the existing Regulations of Annual System. 4. Attendance 4.1 A student attending at least 75% of the total number of classes* held shall be allowed to sit for the concerned Semester Examinations subject to fulfilment of other conditions laid down in the regulations. 4.2 A student attending at least 60% but less than 75% of the total number of classes* held shall be allowed to sit for the concerned Semester Examinations subject to the payment of prescribed condonation fees and fulfilment of other conditions laid down in the regulations. -

Contents SEAGULL Theatre QUARTERLY

S T Q Contents SEAGULL THeatre QUARTERLY Issue 18 June 1998 2 EDITORIAL Editor 3 Anjum Katyal BELIEVED -IN THEATRE : AN EXCERPT Richard Schechner Editorial Consultant Samik Bandyopadhyay 10 ‘A WORLD WHERE AND IS MORE IMPORTANT THAN OR ’ Assistants A DISCUSSION WITH RICHARD SCHECHNER Chaitali Basu Sayoni Basu 24 Vikram Iyengar RESPONSES Makarand Sathe Design Richard Schechner Naveen Kishore 29 ‘COMING OUT WITH MUSIC ’: BUILDING A GAY COMMUNITY Vikram Iyengar 47 INSIDE GAYLAND Rajesh Talwar 50 THE MYLARALINGA TRADITION S. A. Krishnaiah M. N. Venkatesh 54 THEATRE IN POLITICS/POLITICS IN THEATRE Bhaskar Chandavarkar 60 ‘WE DIDN ’T HAVE ANY OTHER LIFE THAN THE THEATRE ’ B. Jayshree 62 ‘THIS IS A PLAY THAT KICKS SOCIETY IN THE GUTS ’ AN INTERVIEW WITH B. JAYSHREE Acknowledgements 70 We thank all contributors and A SPACE FOR THEATRE : THE PRITHVI THEATRE FESTIVAL interviewees for their photographs, Sameera Iyengar specially Swamp Gravy and Performance Research for their 80 prompt cooperation. ‘MAKING A THINKING DANCER ’ AN INTERVIEW WITH NARENDRA SHARMA Published by Naveen Kishore for 92 The Seagull Foundation for the Arts, THEATRE LOG 26 Circus Avenue, The Action Players’ 25th Year Calcutta 700017 Asom Ranga Katha’s Theatre Workshop Donga Satteiah : An Adaptation of Charandas Chor Printed at Theatre Workshop for the Tribals of Telengana Laurens & Co 9 Crooked Lane, Calcutta 700 069 S T Q SEAGULL THeatre QUARTERLY Dear friend, Four years ago, we started a theatre journal. It was an experiment. Lots of questions. Would a journal in English work? Who would our readers be? What kind of material would they want?Was there enough interesting and diverse work being done in theatre to sustain a journal, to feed it on an ongoing basis with enough material? Who would write for the journal? How would we collect material that suited the indepth attention we wanted to give the subjects we covered? Alongside the questions were some convictions. -

Performing Nautanki: Popular Community Folk

PERFORMING NAUTANKI: POPULAR COMMUNITY FOLK PERFORMANCES AS SITES OF DIALOGUE AND SOCIAL CHANGE A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Communication of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Devendra Sharma August 2006 © 2006 Devendra Sharma All Rights Reserved This dissertation entitled PERFORMING NAUTANKI: POPULAR COMMUNITY FOLK PERFORMANCES AS SITES OF DIALOGUE AND SOCIAL CHANGE by DEVENDRA SHARMA has been approved for the School of Communication Studies and the Scripps College of Communication by Arvind Singhal Professor, School of Communication Studies Gregory J. Shepherd Dean, Scripps College of Communication Abstract SHARMA, DEVENDRA, Ph.D., August 2006, Communication Studies PERFORMING NAUTANKI: POPULAR COMMUNITY FOLK PERFORMANCES AS SITES OF DIALOGUE AND SOCIAL CHANGE (250 pp.) Director of Dissertation: Arvind Singhal This research analyzes the communicative dimensions of Nautanki, a highly popular folk performance tradition in rural north India. It explores how Nautanki creates participatory dialogue, builds community, and opens up possibilities for social change in rural India. It also tries to understand the position of Nautanki as a traditional folk form in a continuously changing global world. This research uses Mikhail Bakhtin’s concept of performance as carnival and Dwight Conquergood’s notion of performance as an alternative to textocentrism to understand Nautanki as a community folk form and an expression of ordinary rural Indian culture. The research employed reflexive and native ethnographic methods. The author, himself a Nautanki artist, used his dual position as a performer-scholar to understand Nautanki’s role in rural communities. Specifically, the method included observation of participation and in-depth interviews with Nautanki performers, writers, troupe managers, owners, their clients, and audience members in the field. -

Current-Affairs.Pdf

TNPSC - PREVIOUS YEAR QUESTIONS CURRENT AFFAIRS SI.NO CONTENTS PAGE.NO CURRENT AFFAIRS 1. GROUP - I 3 – 15 2. GROUP – II 16-20 3. GROUP – IIA 21-26 4. GROUP – IV 27 – 35 www.chennaiiasacademy.com Vellore – 9043211311, Tiruvannamalai - 9043211411 Page 2 TNPSC - GROUP - I PRELIMS – 2011 8. The longest solar eclipse of the 21st Century PREVIOUS YEARS QUESTIONS occurred on. CURRENT AFFAIRS A) July 29,2009 B) July 18,2009 C) July 22,2009 D) June 22,2009 1. National Remote Sensing Centre is located 9. Shri Sundarlal Bahuguna received at. ________ award. A) Hyderabad B) Chennai A) Padma Bhushan C) Bangalore D) New Delhi. B) Padma Vibhushan 2. Which one of the Assembly by- elections C) Padma shri saw the highest voter turnout 2010 in Tamil D) Oscar Nadu? 10. Reservation was provided to women in A)Thirumangalam B) Thirupatthur Government services by. C) Pennagaram D) Ponneri A) Jayalalitha 3. The world classical Tamil Conference held B) M.G. Ramachandran on July,2010 is C) Rajaji A) Sixth world Tamil Conference D) M.Karunanidhi B) Seventh world Tamil conference. 11. Delhi High court allowed plea of gay rights C) Ninth world Tamil Conference activists and legalized gay sex in. D) Tenth world Tamil conference. A) 2006 B) 2007 4. Which one of the following is not correctly C) 2008 D) 2009 matched? 12. „Bhuvan‟ the new web based mapping of A) Surjit Singh Barnala -Chancellor of earth was developed by. Universities of Tamil Nadu. A) NASA B) ISRO B) Fakruddin Ali Ahmed C) ESA D) Russia. - Former president of India. -

PAPER-14 MODULE-9 Women in Hindi Theatre A) Personal Details

PAPER-14 MODULE-9 Women in Hindi Theatre A) Personal Details Role Name Affiliation Principal Investigator Prof. Allahabad University, SumitaParmar Allahabad Paper Coordinator Prof. S.D. Roy Allahabad Univesity, Allahabad Content Writer/Author Dr. Jaya Kapoor Allahabad University, (CW) Allahabad Content Reviewer Prof. S.D. Roy Allahabad University, (CR) Allahabad Language Editor (LE) Prof. Sumita Allahabad University, Parmar Allahabad (B) Description of Module Items Description of Module Subject Name Theatre Studies Paper Name Women , Theatre and the Fine Arts Module Name/ Title Women in Hindi Theatre Module ID PAPER-14 MODULE-9 Pre-requisites The Reader is expected to have a brief knowledge of the history of Parsi theatre, the nationalist movement, the origins of IPTA, and NSD and the general growth of Indian theatre. Objectives To introduce the reader to the role of women in the Hindi theatre, placing it simultaneously in the context of the growth of the Hindi theatre Keywords Hindi theatre, Parsi theatre, IPTA, NSD Women in Hindi Theatre Introduction Introducing the emergence of women in Theatre in Hindi the Oxford Companion to Indian Theatre says “among Indian languages, Hindi theatre has possibly the largest number of active women writers and directors.” (pg. 158) It also adds that this is an achievement in a language where till the middle of the twentieth century, association with theatre was not considered a very appreciable thing. When we look at the development of Hindi theatre, we are broadly looking at a very big region of central and Northern India and also Bombay since a lot of growth in theatre took place in conjunction with the film industry.