202 Feiner Snippet.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kol Hamevaser 2.1:Torahumadah.Qxd

Kol Hamevaser Contents Volume 2, Issue 1 Staff September 20, 2008 Managing Editors Alex Ozar 3 Editorial: On Selihot Ben Kandel Rabbi Shalom Carmy 4-5 On Optimism and Freedom: A Preface to Rav Gilah Kletenik Kook’s Orot Ha-Teshuvah Alex Ozar Emmanuel Sanders 6-7 Levinas and the Possibility of Prayer Shaul Seidler-Feller Ari Lamm 7-9 An Interview with Rabbi Hershel Reichman Staff Writers Rena Wiesen 9-10 Praying with Passion Ruthie Just Braffman Gilah Kletenik 10 The Supernatural, Social Justice, and Spirituality Marlon Danilewitz Simcha Gross 11 Lions, Tigers, and Sin - Oh My! Ben Greenfield Noah Greenfield Ruthie Just Braffman 12 Lord, Get Me High Simcha Gross Joseph Attias 13 Finding Meaning in Teshuvah Emmanuel Sanders Devora Stechler Rena Wiesen Special Features Interviewer Ari Lamm Gilah Kletenik 14-15 Interview with Rabbi Marc Angel on His Recently Published Novel, The Search Committee Typesetters Yossi Steinberger Aryeh Greenbaum Upcoming Issue In the spirit of the current political season and in advance of the pres- idential elections, the upcoming edition of Kol Hamevaser will be on Layout Editor the topic of Politics and Leadership. The topic burgeons with poten- Jason Ast tial, so get ready to write, read, and explore all about Jews, Politics, and Leadership. Think: King Solomon, the Israel Lobby, Jewish Sovereignty, Exilarchs, Art Editor Rebbetsins, Covenant and Social Contract, Tzipi Livni, Jewish non- Avi Feld profits, Serarah, Henry Kissinger, the Rebbe, Va'ad Arba Aratsot, and much more! About Kol Hamevaser The deadline for submissions is October 12, 2008. the current editors of Kol Hamevaser would like to thank and applaud our outgoing editors, David Lasher and Mattan Erder, Kol Hamevaser is a magazine of Jewish thought dedicated to spark- as well as Gilah Kletenik and Sefi Lerner for their efforts to- ing the discussion of Jewish issues on the Yeshiva University campus. -

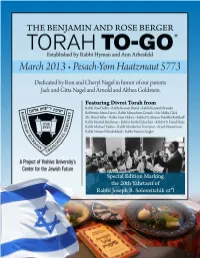

Pesach to Go - 5773.Pdf

1 Yeshiva University • The Benjamin and Rose Berger Torah To-Go Series• Nissan 5773 Richard M. Joel, President, Yeshiva University Rabbi Kenneth Brander, The David Mitzner Dean, Center for the Jewish Future Rabbi Joshua Flug, General Editor Rabbi Michael Dubitsky, Editor Andrea Kahn, Copy Editor Copyright © 2013 All rights reserved by Yeshiva University Yeshiva University Center for the Jewish Future 500 West 185th Street, Suite 413, New York, NY 10033 • [email protected] • 212.960.5263 This publication contains words of Torah. Please treat it with appropriate respect. For sponsorship opportunities, please contact Genene Kaye at 212.960.0137 or [email protected]. 2 Yeshiva University • The Benjamin and Rose Berger Torah To-Go Series• Nissan 5773 Table of Contents Pesach/Yom Haatzmaut 2013/5773 Rabbi Akiva’s Seder Table: An Introduction Rabbi Kenneth Brander . Page 7 Reflections on Rav Soloveitchik zt"l Growing up in Boston An Interview with Rebbetzin Meira Davis . Page 11 Insights into Pesach On the Study of Haggadah: A Note on Arami Oved Avi and Biblical Intertextuality Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik zt"l . Page 15 Use of the Term Makom, Omnipresent, in the Haggadah Rabbi Yosef Adler . Page 19 What Is Judaism? Rabbi Reuven Brand . Page 21 Why Don’t We Recite Shehecheyanu on Sefiras ha-Omer Rabbi Menachem Genack . Page 29 The Dual Aspect of the Four Cups: A Core Idea of Pesach from the Rav zt”l Rabbi Hershel Reichman . Page 33 Charoses: Why Don’t we Recite a Beracha? Rabbi Hershel Schachter . Page 35 Insights from the Rav on the “Maggid” Section of the Haggadah Rabbi Michael Taubes . -

J. David Bleich SURVEY of RECENT HALAKHIC PERIODICAL

J. David Bleich SURVEY OF RECENT HALAKHIC PERIODICAL LITERATURE ENTERING A NON-JEWISH HOUSE OF WORSHIP Jewish attitudes and practices are generally fi rmly grounded in Jewish tradition. At times the sources are clear and unequivocal; at other times the sources are obscure and even speculative. Oftentimes, there is little correlation between the normative authority of the underlying source and the tenacity with which its expression is maintained by the simplest of Jews. Quite apart from any halakhic infraction involved, for most Jews of the old school refusal to cross the threshold of a non-Jewish house of worship is a Pavlovian refl ex rather than a reasoned response. Nevertheless, this is an instance in which emotion and intellect are at one. I. THE STATUS OF CHRISTIAN BELIEF The question of the permissibility of entering church premises arises from the antecedent premise that, as a matter of normative Halakhah, Judaism regards acceptance of the notion of the Trinity as antithetical to the doc- trine of Divine Unity; perforce Judaism regards worship of a triune deity as a form of idolatry. Christians confl ate Trinitarianism with monotheism despite the self-contradiction that renders simultaneous acceptance of both doctrines an absurdity. Indeed, as Tertullian is famously quoted in defi ning his own Christian belief: “Credo quia ineptum—I believe be- cause it is absurd.”1 In that aphorism is a deeply-rooted desire on the part of Christians to be monotheists; in the words of rabbinic writers, “Their heart is directed toward Heaven.” Reconciliation of that desire with an antithetical belief in a triune God requires nothing less than a leap of faith on their part. -

KAJ NEWSLETTER a Monthly Publication of K’Hal Adath Jeshurun Volume 48 Number 1

September 5, ‘17 י"ד אלול תשע"ז KAJ NEWSLETTER A monthly publication of K’hal Adath Jeshurun Volume 48 Number 1 MESSAGE FROM THE BOARD .כתיבה וחתימה טובה The Board of Trustees wishes all our members and friends a ,רב זכריה בן רבקה Please continue to be mispallel for Rav Gelley .רפואה שלמה for a WELCOME BACK The KAJ Newsletter welcomes back all its readers from what we hope was a pleasant and restful summer. At the same time, we wish a Tzeisechem LeSholom to our members’ children who have left, or will soon be leaving, for a year of study, whether in Eretz Yisroel, America or elsewhere. As we begin our 48th year of publication, we would like to remind you, our readership, that it is through your interest and participation that the Newsletter can reach its full potential as a vehicle for the communication of our Kehilla’s newsworthy events. Submissions, ideas and comments are most welcome, and will be reviewed. They can be emailed to [email protected]. Alternatively, letters and articles can be submitted to the Kehilla office. מראה מקומות לדרשת מוהר''ר ישראל נתן הלוי מנטל שליט''א שבת שובה תשע''ח לפ''ק בענין תוספת שבת ויו"ט ויום הכפורים ר"ה דף ט' ע"א רמב"ם פ"א שביתת עשור הל' א' ,ד', ו' טור או"ח סי' רס"א בב"י סוד"ה וזמנו, וטור סי' תר"ח תוס' פסחים צ"ט: ד"ה עד שתחשך, תוס' ר' יהודה חסיד ברכות כ"ז. ד"ה דרב תוס' כתובות מ"ז. -

Guide to the Yeshiva

Guide to the Yeshiva The Undergraduate Torah Experience For answers to all your Yeshiva questions, email [email protected] Our Yeshiva has a long and profound history and legacy of Undergraduate Torah Studies Torah scholarship and spiritual greatness. Our roots stretch back to the Torah of Volozhin and Brisk and continue in WELCOME TO THE YESHIVA! our Yeshiva with such luminaries as Rav Shimon Shkop We have assembled in one Yeshiva an unparalleled cadre of roshei yeshiva, rebbeim, mashgichim and support staff to enable you to have an uplifting and enriching Torah experience. We hope you will take and Rav Yosef Dov Soloveitchik. As you enter Yeshiva, you full advantage of all the Yeshiva has to offer. will not only partake of the great heritage of our past but, Hatzlacha Rabbah! together with your rebbeim, will forge a glorious future. Rabbi Dr. Ari Berman Rabbi Zevulun Charlop President Dean Emeritus Special Assistant to the President Rabbi Menachem Penner Rabbi Dr. Yosef Kalinsky The Max and Marion Grill Dean Associate Dean Glueck Center, Room 632 Undergraduate Torah Studies 646.592.4063 Glueck Center, Room 632 [email protected] 646.592.4068 [email protected] For answers to all your Yeshiva questions, email [email protected] 1 Undergraduate Torah Studies Programs Yeshiva Program/Mazer School The James Striar School (JSS) of Talmudic Studies (MYP) This path is intended for students new to Hebrew language and textual study who aspire to attain This program offers an advanced and sophisticated a broad-based Jewish philosophical and text classical yeshiva experience. Students engage education. Led by a dynamic, caring faculty and in in-depth study of Talmud with our world- with daily mentoring from students at YU’s renowned roshei yeshiva. -

In This Issue Divrei Torah From: Rabbi Meir Goldwicht Rabbi Dr

A PUBLICATION OF THE RABBINIC ALUMNI OF THE RABBI ISAAC ELCHANAN THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY • AN AFFILIATE OF YESHIVA UNIVERSITY CHAV RUSA Volume 45 • Number 2 אין התורה נקנית אלא בחבורה (ברכות סג:) January 2011 • Shevat 5771 In This Issue Divrei Torah from: Rabbi Meir Goldwicht Rabbi Dr. David Horwitz Rabbi Naphtali Weisz ראש השנה לאילנות New Rabbinic On Being a Maggid: Advisory The Storytelling of Committee Rabbi Hershel Schachter Page 4 Page 15 In This Issue Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary Page 3 News from RIETS The 2010 RIETS dinner, a reunion shiur for former Richard M. Joel students of Rabbi Hershel Schachter, and the new PRESIDENT, YESHIVA UNIVersity Rabbinic Advisory Committee. Rabbi Dr. Norman Lamm CHANCELLOR, YeshiVA UNIVersity ROSH HAYESHIVA, RIETS Rabbi Julius Berman C hairman of the B oard of T rustees , R I E T S Page 12 Musmakhim in the Limelight Longevity in the rabbinate Rabbi Yona Reiss M A X and M arion G ri L L Dean , R I E T S Rabbi Kenneth Brander DAVID MITZNER DEAN, CENTER for THE JEWISH FUTURE Rabbi Zevulun Charlop DEAN EMERITUS, RIETS SPECIAL ADVISOR to THE PRESIDENT ON YeshiVA Affairs Page 18 Practical Halachah A Renewable Light Unto the Nations Rabbi Robert Hirt VICE PRESIDENT EMERITUS, RIETS By Rabbi Naphtali Weisz Rabbi Chaim Bronstein Administrator, RIETS Page 5 Special Feature Page 15 Special Feature CHAVRUSA Orthodox Forum Marks On Being a Maggid: A Look A PUBLication OF RIETS RABBINIC ALUMNI 20 Years of Service to the at the Storytelling of Rabbi Rabbi Ronald L. Schwarzberg Community Hershel Schachter Director, THE MORRIS AND Gertrude BIENENFELD By Zev Eleff D epartment of J ewish C areer D E V E Lopment AND PLacement Page 6 Divrei Chizuk Page 19 Book Reviews Rabbi Elly Krimsky A Potential Holiday Editor, CHAVRUSA By Rabbi Meir Goldwicht Page 8 Back to the Page 21 Lifecycles Rabbi Levi Mostofsky Associate Editor, CHAVRUSA Beit Midrash Tu Bi-Shevat and the Sanc- Ms. -

TORAH TO-GO® Established by Rabbi Hyman and Ann Arbesfeld April 2015 • Pesach-Yom Haatzmaut 5775

Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary Yeshiva University Center for the Jewish Future THE BENJAMIN AND ROSE BERGER TORAH TO-GO® Established by Rabbi Hyman and Ann Arbesfeld April 2015 • Pesach-Yom Haatzmaut 5775 Dedicated in memory of Cantor Jerome L. Simons Featuring Divrei Torah from Rabbi Kenneth Brander • Rabbi Assaf Bednarsh Rabbi Josh Blass • Rabbi Reuven Brand Rabbi Daniel Z. Feldman Rabbi Lawrence Hajioff • Rona Novick, PhD Rabbi Uri Orlian • Rabbi Ari Sytner Rabbi Mordechai Torczyner • Rabbi Ari Zahtz Insights on Yom Haatzmaut from Rabbi Naphtali Lavenda Rebbetzin Meira Davis Rabbi Kenny Schiowitz 1 Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary • The Benjamin and Rose Berger CJF Torah To-Go Series • Pesach 5775 We thank the following synagogues who have pledged to be Pillars of the Torah To-Go® project Congregation Kehillat Shaarei United Orthodox Beth Shalom Yonah Menachem Synagogues Rochester, NY Modiin, Israel Houston, TX Congregation The Jewish Center Young Israel of Shaarei Tefillah New York, NY New Hyde Park Newton Centre, MA New Hyde Park, NY For nearly a decade, the Benajmin and Rose Berger Torah To-Go® series has provided communities throughout North America and Israel with the highest quality Torah articles on topics relevant to Jewish holidays throughout the year. We are pleased to present a dramatic change in both layout and content that will further widen the appeal of the publication. You will notice that we have moved to a more magazine-like format that is both easier to read and more graphically engaging. In addition, you will discover that the articles project a greater range in both scholarly and popular interest, providing the highest level of Torah content, with inspiration and eloquence. -

Shomrei Torah

Shomrei Torah Vayeishev 21 Kislev, 5778/ December 8-9, 2017 Benjamin Yudin, Rabbi Andrew Markowitz, Associate Rabbi Parsha/Haftorah: Artscroll: 198/1142 Hertz: 141/152 The Living Torah: 182/1083 Daf Hashavuah - Beitzah 58 MAZAL TOV Shabbat Schedule Dossy and Leo Brandstatter on being honored at the Project Ezrah Dinner this Motzei Shabbat. Erev Shabbat - December 8th HAKARAT HaTOV Candle Lighting 4:10pm Ba’al Kriah Upstairs - Avraham Meyers Mincha/ Kabbalat Shabbat 4:15pm Ba’al Kriah Downstairs - Daniel Krich Shabbat - December 9th Kiddush Upstairs– Sponsored by Wolina and Morris Shapiro in honor of their 50th Wedding Anniversary, Wolina's birthday, the Bar Mitzvah of their grandson Ben, the birthdays of their grandchildren Laila, Sadie, Morning Daniel and Aaron, and in thanks to the Congregation for their prayers one year ago. Sof Z’man Kriyat sh’ma 9:29am Kiddush Downstairs- Sponsored by Moshe and Avital Osherovitz to celebrate the birth of Lielle. Daf Yomi - Shevuot 11 8:00am The Heiser family would like to thank the Shomrei Torah family for their love and support during our very difficult time. We so appreciate your calls and visits and feel blessed to be part of such a wonderful communi- Shacharit ty. ברוכים הבאים Beit Medrash 8:00am Main Shul 8:45am Mouchka and Dov Heller, who are visiting Fair Lawn this Shabbat. Downstairs 9:00am Beth and Hillel Max, who are visiting Fair Lawn this Shabbat. Shabbat Afternoon Lea Epstein and Ben Sanders, who are visiting Fair Lawn this Shabbat. Rivka and Aaron Tropper, who are visiting Fair Lawn this Shabbat. -

Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik's

The Catholic University of America, Columbus School of Law CUA Law Scholarship Repository Scholarly Articles and Other Contributions Faculty Scholarship 2005 Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik’s ‘Confrontation’: A Reassessment Marshall J. Breger The Catholic University of America, Columbus School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.edu/scholar Part of the Religion Law Commons Recommended Citation Marshall J. Breger, Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik’s ‘Confrontation’: A Reassessment, 1 STUD. CHRISTIAN- JEWISH REL. 151 (2005). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at CUA Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scholarly Articles and Other Contributions by an authorized administrator of CUA Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Studies in Christian-Jewish Relations A peer-reviewed e-journal of the Council of Centers in Jewish-Christian Relations Published by the Center for Christian-Jewish Learning at Boston College A Reassessment of Rav Soloveitchik’s Essay on Interfaith Dialogue: “Confrontation” Marshall J. Breger Columbus School of Law, Catholic University of America Volume 1 (2005-2006): pp. 151-169 http://escholarship.bc.edu/scjr/vol1/iss1/art18 Studies in Christian-Jewish Relations Volume 1, (2005-2006): 151-169 Introduction1 by Boston College.5 That reassessment in turn brought forth further comments.6 Below are some of my own reactions to We recently passed the fortieth anniversary of Rabbi this ongoing debate. Soloveitchik’s magisterial essay on interreligious dialogue, Soloveitchik’s essay presents a complex argument Confrontation.2 Rabbi Soloveitchik (1903-1993) was the based on a moral anthropology embedded in an leading modern Orthodox religious authority in America interpretation of the biblical account of the creation of man.7 during his lifetime and his religious opinions and rulings are The article develops three paradigms of human nature. -

WHEN MAY ONE ASK for a SECOND HALAKHIC OPINION Rabbi Aryeh Klapper, Dean

Shoftim, September 10, 2016 www.torahleadership.org WHEN MAY ONE ASK FOR A SECOND HALAKHIC OPINION Rabbi Aryeh Klapper, Dean Dear Rabbi Klapper, objection to directing questions to rabbis who are experts in Yesterday, I asked the rabbi of my shul a halakhic sh’eilah, and he gave me a particular fields, or who know your mind and soul better with regard machmir answer that feels wrong, and that I think may damage my relationship to specific issues, or who share your values in particular areas. The with my husband. I think you would give a different answer. I’ve always felt phrase “asei lekha rav”, meaning that one should seek to have a that “shitah-shopping” lacked integrity, so I feel very stuck. Am I permitted to primary Torah mentor, is often excellent advice, but pretending that ask you the same question, and would you consider answering it? such a relationship exists when it does not can do great harm. In its Sincerely, original contexts (Pirkei Avot 1:6 and 1:16) aseh lekha rav it does not Jane Tzviyah relate to asking live halakhic sheilot, and indeed R. Ovadiah miBartenura in his commentary there emphasizes that one should Dear Ms. Tzviyah, learn halakhic reasoning and application from multiple teachers. דרכיה דרכי Your sense that shopping for a lenient opinion lacks integrity is Furthermore, a key marker of authentic Torah is that נעם deeply rooted in our masoret. , “All her ways are pleasantness”, and it violates the nature and The Talmud in three places (Berakhot 63b, Chullin 44b, Niddah purpose of halakhah when a psak causes unnecessary moral 30b) cites the following beraita: discomfort or emotional anguish, let alone harms a marriage. -

THE BENJAMIN and ROSE BERGER TO-GO® Establishedtorah by Rabbi Hyman and Ann Arbesfeld • April 2018 • Yom Haatzmaut 5778

Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary • YU Center for the Jewish Future THE BENJAMIN AND ROSE BERGER TO-GO® EstablishedTORAH by Rabbi Hyman and Ann Arbesfeld • April 2018 • Yom Haatzmaut 5778 Dedicated in memory of Cantor Jerome L. Simons Israel at 70 Commemorating the 25th Seven Decades of Israel Yahrtzeit of Rabbi Joseph B. Top Seven Torah Issues Soloveitchik zt”l from the 70 Years of the The Rav on Religious Zionism State of Israel We thank the following synagogues which have pledged to be Pillars of the Torah To-Go® project Beth David Synagogue Congregation Ohab Zedek Young Israel of West Hartford, CT New York, NY Century City Los Angeles, CA Beth Jacob Congregation Congregation Beverly Hills, CA Shaarei Tefillah Young Israel of Newton Centre, MA New Hyde Park Bnai Israel – Ohev Zedek New Hyde Park, NY Philadelphia, PA Green Road Synagogue Beachwood, OH Young Israel of Congregation Scarsdale Ahavas Achim The Jewish Center Scarsdale, NY Highland Park, NJ New York, NY Young Israel of Congregation Benai Asher Jewish Center of Toco Hills The Sephardic Synagogue Brighton Beach Atlanta, GA of Long Beach Brooklyn, NY Long Beach, NY Young Israel of Koenig Family Foundation Congregation Brooklyn, NY West Hartford Beth Sholom West Hartford, CT Young Israel of Providence, RI Young Israel of Lawrence-Cedarhurst Cedarhurst, NY West Hempstead West Hempstead, NY Rabbi Dr. Ari Berman, President, Yeshiva University Rabbi Yaakov Glasser, David Mitzner Dean, Center for the Jewish Future Rabbi Menachem Penner, Max and Marion Grill Dean, Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary Rabbi Robert Shur, Series Editor Rabbi Joshua Flug, General Editor Rabbi Michael Dubitsky, Content Editor Andrea Kahn, Copy Editor Copyright © 2018 All rights reserved by Yeshiva University Yeshiva University Center for the Jewish Future 500 West 185th Street, Suite 419, New York, NY 10033 • [email protected] • 212.960.0074 This publication contains words of Torah. -

Yeshiva University • the Benjamin and Rose Berger Torah To-Go Series• Tishrei 5774

1 Yeshiva University • The Benjamin and Rose Berger Torah To-Go Series• Tishrei 5774 Tishrei 5774 Dear Friends, It is our pleasure to present to you this year’s first issue of Yeshiva University’s Benjamin and may ספר Rose Berger Torah To-Go® series. It is our sincere hope that the Torah found in this .(study) לימוד holiday) and your) יום טוב serve to enhance your We have designed this project not only for the individual, studying alone, but perhaps even a pair studying together) that wish to work through the study matter) חברותא more for a together, or a group engaged in facilitated study. להגדיל תורה ,With this material, we invite you to join our Beit Midrash, wherever you may be to enjoy the splendor of Torah) and to engage in discussing issues that touch on a) ולהאדירה most contemporary matter, and are rooted in the timeless arguments of our great sages from throughout the generations. Ketiva V'Chatima Tova, The Torah To-Go® Editorial Team Richard M. Joel, President and Bravmann Family University Professor, Yeshiva University Rabbi Kenneth Brander, Vice President for University and Community Life, Yeshiva University and The David Mitzner Dean, Center for the Jewish Future Rabbi Joshua Flug, General Editor Rabbi Michael Dubitsky, Editor Andrea Kahn, Copy Editor Copyright © 2013 All rights reserved by Yeshiva University Yeshiva University Center for the Jewish Future 500 West 185th Street, Suite 413, New York, NY 10033 • [email protected] • 212.960.5263 This publication contains words of Torah. Please treat it with appropriate respect. For sponsorship opportunities, please contact Genene Kaye at 212.960.0137 or [email protected].