Color Entrenchment in Middle-School English Speakers: Cognitive Salience Index Applied to Color Listing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Premium 275+ Strong Colors

PREMIUM 275+ STRONG COLORS Die weltweit erste Street Art optimierte Sprühdose wurde The worldwide first street art optimized spray can was von Künstlern für Künstler entwickelt. Der hochdeckende developed with artists for artists. The highly opaque classic Klassiker, mit 4-fach gemahlenen Auto-K™ Pigmenten, ist with its 4 times ground Auto-K™ pigments, is the most die zuverlässigste Graffiti-Sprühdose seit 1999. re liable graffiti spray can since 1999. Mit über 275 Farbtönen verfügt das Sortiment der Moreover, with more than 275 color shades MOLOTOW™ MOLOTOW™ PREMIUM außerdem über eine der PREMIUM has one of the biggest spray paint color range. umfangreichsten Sprühdosen-Farbpaletten. PREMIUM PREMIUM Transparent 400 ml | 327300 PREMIUM Transparent PREMIUM Neon 400 ml | 327499 GRAFFITI PREMIUM 400 ml | 327000 SPRAY PAINT SEMI GLOSS MATT MATT HIGHLY HIGHEST UV AND GOOD UV AND GOOD UV RESISTANCE THE ORIGINAL WEATHER RESISTANCE WEATHER RESISTANCE WITH SEALING SINCE 1999 OPAQUE 252 COLOR SHADES TRANSPARENT 15 COLOR SHADES + 2 CLEAR COATINGS NEON 8 COLOR SHADES #181- #001 jasmin yellow 327001 #032 MAD C cherry red 327188 #063 purple violet 327138 #094 shock blue 327032 #122 riviera pastel 327216 #153 grasshopper 327064 nature green middle 327252 #203 cocoa middle 327234 #228 grey blue light 327177 2 zinc yellow 327006 signal red 327014 crocus 327199 tulip blue light 327213 riviera light 327072 cream green 327058 mustard 327049 cocoa 327126 pebble grey 327238 Händlerstempel ∙ dealer stamp Issue 12/20 #002 #033 #064 #095 #123 #154 #182 #204 #229 #182- #204- #003 cadmium yellow 327082 #034 apricot 327116 #065 lavender 327200 #096 tulip blue middle 327214 #124 TASTE riviera middle 327217 #155 hippie green 327063 mustard yellow 327262 caramel light 327253 #230 marble 327239 1 1 #182- #004 signal yellow 327165 #035 salmon orange 327134 #066 lilac 327201 #097 tulip blue 327033 #125 riviera dark 327073 #156 BACON wasabi 327222 khaki green 327263 #205 caramel 327091 #231 signal white 327160 2 4 Item-No. -

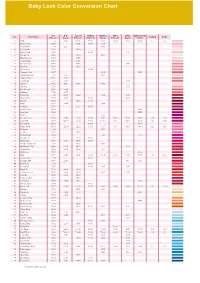

Baby Lock Color Conversion Chart

Tacony_quickguide_37-コピー 05.7.6 9:01 AM ページ 37 Baby Lock Color Conversion Chart R.A. R.A. Isacord Madeira Madeira Sulky Sulky Güetermann No. Color Name Polyester Rayon Polyester Polyneon Rayon Polyester Rayon Dekor Country Embr. 1 Pink 5523 2223 *0180 1921 1121 1224 1108 *4830 155 085 2 Dusty Rose 5675 2155 1816 1108 3 Petal Pink 7701 2255 1015 4 Light Pink 9030 1860 5 Light Coral 9078 1915 1148 6 Ginger Jar 9080 2170 1115 7 Heather Mist 9070 1755 8 Champagne 9063 2051 9 Dark Mauve 9015 2153 1119 10 Heather 9164 2152 11 Neon Pink 5711 1948 12 Comfort Pink 9077 1119 5435 13 Mountain Rose 5795 2373 1315 14 Cherry Pink 5544 2244 15 Carnation 5537 2509 1188 16 Salmon 9073 2553 1840 1018 17 Shrimp 5546 1154 18 Dark Coral 9065 2246 19 Bitteroot 7709 2277 20 Burgundy 5549 2249 2022 1182 1169 21 Warm Wine 5796 2622 1782 1309 22 Russet 5552 2123 1781 23 Plum 9055 2498 1389 24 Maroon 5676 2115 1919 25 Royal Crest 9162 5400 26 Hot Pink 5560 5385 27 Ruby 5797 1183 28 Dark Fuchsia 5804 2504 *2300 1984 1383 1533 1533 *4810 126 107 29 Carmine 5561 *2419 2300 1986 *1081 1511 *1511 5315 158 807 30 Dark Pink 9161 1994 4810 31 Deep Rose 9168 *2508 2520 1721 *1117 1154 1307 *4941 024 086 32 Begonia 5528 1117 33 Azalea 7712 2220 34 Rubine Red 9012 1186 4740 35 Strawberry 5732 2320 1910 36 Devil Red 7706 2507 1906 1986 37 Candy Apple Red 5807 1805 1081 38 Hollyhock Red 9006 2267 1912 1311 39 Toasty Red 9002 2418 1902 1181 40 Wild Fire 5567 4700 41 Red 5678 2505 2101 1637 *1037 1037 *1037 *4740 149 800 42 Jockey Red 5581 1747 43 Radiant Red 5566 2219 561 4731 -

Pantone Spring-Summer 2021 Fashion Color Forecast

Pantone Fashion Color Forecasting for Spring/Summer 2021 About the Spring/Summer 2021 Color Palette The colors for Spring/Summer 2021 New York emphasize our desire for a range of color that inspires ingenuity and inventiveness – colors whose versatility transcend the seasons and allow for more freedom of choice - colors that lend themselves to original color statements and whose flexibility easily adapts to our new and more fragmented lifestyle. Marigold Cerulean Rust Illuminating French Blue 1. Marigold: Dusty Orange MX516 @ 3.0%OWG WashFast: Apricot WF229 @ 1.5%OWG 2. Cerulean: Baby Blue MX444 @ 0.5%OWG WashFast: Nautical Blue WF415 @ 1.0%OWG 3. Rust: Pumpkin Spice MX2216 @ 4.0%OWG WashFast: Terra Cotta WF236 @ 1.5%OWG 4. Illuminating: Sun Yellow MX108 @ 3.0%OWG WashFast: Sun Yellow WF119 @ 1.5%OWG 5. French Blue: Basic Blue MX400 @ 4.0%OWG WashFast: Bright Blue WF440 @ 1.5%OWG Green Ash Burnt Coral Mint Amethyst Orchid Raspberry Sorbet 1. Green Ash: Cayman Isle Green MX7132 @ 2.0%OWG WashFast: Spearmint WF723 @ 0.5%OWG 2. Burnt Coral: Rose Bud MX3216 @ 1.5%OWG WashFast: Salmon WF311 @ 0.75%OWG 3. Mint: Marine MX435 @ 2.5%OWG WashFast: Ivy WF733 @ 1.5%OWG 4. Amethyst Orchid: Wisteria MX820 @ 3.0%OWG WashFast: Purple WF819 @ 0.75%OWG 5. Raspberry Sorbet: Watermelon MX302 @ 3.0%OWG WashFast: Raspberry Sorbet WF341 @ 1.5%OWG Please note: These are the closest matches from our line of MX and WashFast Dyes. Please sample before going into production. The colors may need to be modified slightly on your choice of cloth or fiber. -

DMC-Color-Families-Listing.Pdf

Color Families DMC® Embroidery Floss Colors Color Description Color Description Color Description 3713 Very Light Salmon 225 Ultra Very Light Shell Pink 155 Medium Dark Blue Violet 761 Light Salmon 224 Very Light Shell Pink 3746 Dark Blue Violet 760 Salmon 152 Medium Light Shell Pink 333 Very Dark Blue Violet 3712 Medium Salmon 223 Light Shell Pink 157 Very Light Cornflower Blue 3328 Dark Salmon 3722 Medium Shell Pink 794 Light Cornflower Blue 347 Very Dark Salmon 3721 Dark Shell Pink 793 Medium Cornflower Blue 353 Peach 3880 Medium Very Dark Shell Pink 792 Dark Cornflower Blue 352 Light Coral 221 Very Dark Shell Pink 158 Medium Very Dark Cornflower Blue 351 Coral 778 Very Light Antique Mauve 791 Very Dark Cornflower Blue 350 Medium Coral 3727 Light Antique Mauve 3807 Cornflower Blue 349 Dark Coral 316 Medium Antique Mauve 3840 Light Lavender Blue 817 Very Dark Coral Red 3726 Dark Antique Mauve 3839 Medium Lavender Blue 3708 Light Melon 315 Medium Dark Antique Mauve 3838 Dark Lavender Blue 3706 Medium Melon 3802 Very Dark Antique Mauve 800 Pale Delft Blue 3705 Dark Melon 902 Very Dark Garnet 809 Delft Blue 3801 Very Dark Melon 3743 Very Light Antique Violet 799 Medium Delft Blue 666 Bright Red 3042 Light Antique Violet 798 Dark Delft Blue 321 Red 3041 Medium Antique Violet 797 Royal Blue 304 Medium Red 3888 Medium Dark Antique Violet 796 Dark Royal Blue 498 Dark Red 3740 Dark Antique Violet 820 Very Dark Royal Blue 816 Gamete 3836 Light Grape 828 Ultra Very Light Sky Blue 815 Medium Garnet 3835 Medium Grape 162 Ultra Very Light Blue 814 -

Color Chart Colorchart

Color Chart AMERICANA ACRYLICS Snow (Titanium) White White Wash Cool White Warm White Light Buttermilk Buttermilk Oyster Beige Antique White Desert Sand Bleached Sand Eggshell Pink Chiffon Baby Blush Cotton Candy Electric Pink Poodleskirt Pink Baby Pink Petal Pink Bubblegum Pink Carousel Pink Royal Fuchsia Wild Berry Peony Pink Boysenberry Pink Dragon Fruit Joyful Pink Razzle Berry Berry Cobbler French Mauve Vintage Pink Terra Coral Blush Pink Coral Scarlet Watermelon Slice Cadmium Red Red Alert Cinnamon Drop True Red Calico Red Cherry Red Tuscan Red Berry Red Santa Red Brilliant Red Primary Red Country Red Tomato Red Naphthol Red Oxblood Burgundy Wine Heritage Brick Alizarin Crimson Deep Burgundy Napa Red Rookwood Red Antique Maroon Mulberry Cranberry Wine Natural Buff Sugared Peach White Peach Warm Beige Coral Cloud Cactus Flower Melon Coral Blush Bright Salmon Peaches 'n Cream Coral Shell Tangerine Bright Orange Jack-O'-Lantern Orange Spiced Pumpkin Tangelo Orange Orange Flame Canyon Orange Warm Sunset Cadmium Orange Dried Clay Persimmon Burnt Orange Georgia Clay Banana Cream Sand Pineapple Sunny Day Lemon Yellow Summer Squash Bright Yellow Cadmium Yellow Yellow Light Golden Yellow Primary Yellow Saffron Yellow Moon Yellow Marigold Golden Straw Yellow Ochre Camel True Ochre Antique Gold Antique Gold Deep Citron Green Margarita Chartreuse Yellow Olive Green Yellow Green Matcha Green Wasabi Green Celery Shoot Antique Green Light Sage Light Lime Pistachio Mint Irish Moss Sweet Mint Sage Mint Mint Julep Green Jadeite Glass Green Tree Jade -

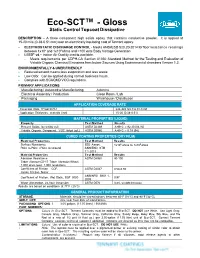

Eco-SCT™ - Gloss Static Control Topcoat Dissipative

Eco-SCT™ - Gloss Static Control Topcoat Dissipative DESCRIPTION – A three component high solids epoxy that contains conductive powder. It is applied at 15-20 mils (0.38-0.51 mm) over an electrically insulating coat of Tennant epoxy. • ELECTROSTATIC DISCHARGE CONTROL - Meets ANSI/ESD S20.20-2014 for floor resis tance readings between 1x105 and 1x109 ohms and <100 volts Body Voltage Generation • LEED® v4 – Indoor Air Quality credits available. - Meets requirements per CDPH-CA Section 01350 Standard Method for the Testing and Evaluation of Volatile Organic Chemical Emissions from Indoor Sources Using Environmental chambers Version 1.2. ENVIRONMENTALLY & USER FRIENDLY • Reduced solvent means less evaporation and less waste. • Low Odor. Can be applied during normal business hours. • Complies with SCAQMD VOC regulations. PRIMARY APPLICATIONS Manufacturing / Automotive Manufacturing Avionics Electrical Assembly / Production Clean Room / Lab Packaging Warehouse / Distribution APPLICATION COVERAGE RATE Coverage Rate, ft2/gal [m2/L] 244-325 [22.7-6.01-8.02] Application Thickness, w et mils [mm] 15-20 [0.38-0.51] MATERIAL PROPERTIES (LIQUID) Property Test Method Results Percent Solids, by w t [by vol] ASTM D2369 A+B+C = 92.30 [84.92] Volatile Organic Compound, VOC, lb/gal [g/L] ASTM D3960 A+B+C = 0.79 [94] CURED COATING PROPERTIES (DRY FILM) Electrical Properties Test Method Results Surface Resistance ESD Assoc. 1x105 ohms to 1x109 ohms Point to Point / Point to Ground A NSI/ES D STM 7.1-2013 Material Properties Test Method Results Abrasion Resistance ASTM D4060 90-100 Taber Abraser CS-17 Taber Abrasion Wheel, 1,000 gram load, 1,000 revolutions Coefficient of Friction – COF, ASTM D2047 0.50-0.55 James Friction Tester ANSI/NFSI B101.1- Coefficient of Friction, Wet Static, BOT 3000 0.97 2009 Water Absorption, 24-hour immersion A STM D570 0.2% w eight increase Results are based on conditions at 77°F (25°C) GENERAL PRODUCT INFORMATION STORAGE: Materials should be stored indoors betw een 65ºF [18ºC] and 90ºF [32ºC]. -

The Duncan to Mayco Conversion Chart

TO CONVERSION CHART CC135 Lake Blue .......................UG72 Wedgewood Blue CC203 Neon Chartreuse ....................UG218 Pear Green CC136 Marlin Blue ...........................UG94 Pansy Purple CC204 Neon Orange......................UG85 Orange Sorbet CC137 Regency Purple.....................UG87 Regal Purple CC205 Neon Green ............................UG218 Pear Green CC140 Morocco Red .................................UG10 Crimson CC206 Neon Red .................................UG208 Fame Red AG401 Marbled Celadon ...................EL131 Turtle Shell CC141 Light Yellow .........................UG46 Bright Yellow AG402 Turquoise Haze ...................EL136 Lapis Lagoon CC142 Canary Yellow ......................UG46 Bright Yellow AG403 Ocean Mist ...............................EL103 Sea Spray CC143 Yellow Orange ..................UG203 Squash Yellow AG404 Winter Fog ...........................EL124 Stormy Blue CC144 Burnt Orange ...................UG203 Squash Yellow AG405 Smoke Stack ..........................EL101 Oyster Shell CC145 Indian Red ..................................UG31 Chocolate CN012 Bright Straw* ............................SC24 Dandelion AG406 Aged Moss .........................EL125 Sahara Sands CC146 Purple ........................................UG93 Wild Violet CN022 Bright Saffron* ..........................SC24 Dandelion AG408 Oyster Shell ................... EL140 Toasted Almond CC148 Deep Turquoise .......................UG19 Electra Blue CN052 Bright Tangerine* ...........SC50 Orange Ya Happy AG409 -

Shinhan TOUCH TWIN Marker Handmade Colorchart

R YR Y GY G BG B PB P RP BR CG WG R1 WINE RED YR211 TIGER LILY Y141 BUTTERCUP YELLOW GY163 GREEN BICE G242 COBALT GREEN PALE BG57 TURQUOISE GREEN LIGHT B171 JADE GREEN PB271 LIGHT BLUE P145 PALE LAVENDER RP196 PALE PINK LIGHT BR111 BROWN BR102 RAW UMBER CG0.5 COOL GREY WG0.5 WARM GREY R2 OLD RED YR23 ORANGE Y36 CREAM GY48 YELLOW GREEN G46 VIVID GREEN BG53 TURQUOISE GREEN B68 TURQUOISE BLUE PB185 PALE BLUE LIGHT P83 LAVENDER RP137 MEDIUM PINK BR94 BRICK BROWN BR99 BRONZE CG1 COOL GREY WG1 WARM GREY R3 ROSE RED YR21 TERRA COTTA Y34 YELLOW GY236 SPRING GREEN G56 MINT GREEN BG50 FOREST GREEN B65 ICE BLUE PB272 GRAYISH BLUE PALE P281 VIOLET RP293 DULL COSMOS PURPLE BR91 NATURAL OAK BR116 CLAY CG2 COOL GREY WG2 WARM GREY R4 VIVID RED YR25 SALMON PINK Y222 GOLDEN YELLOW GY234 LEAF GREEN G55 EMERALD GREEN BG51 DARK GREEN B143 MINT BLUE PB76 SKY BLUE P81 DEEP VIOLET RP86 VIVID REDDISH PURPLE BR93 BURNT ORANGE BR115 FLAX CG3 COOL GREY WG3 WARM GREY R5 CHERRY PINK YR27 POWDER PINK Y44 FRESH GREEN GY47 GRASS GREEN G243 GREEN DEEP BG52 DEEP GREEN B182 FROST BLUE PB183 PHTHALO BLUE P82 LIGHT VIOLET RP87 AZALEA PURPLE BR92 CHOCOLATE BR109 PEARL WHITE CG4 COOL GREY WG4 WARM GREY R10 DEEP RED YR29 BARELEY BEIGE Y35 LEMON YELLOW GY235 SAP GREEN G43 DEEP OLIVE GREEN BG61 PEACOCK GREEN B67 PASTEL BLUE PB69 PRUSSIAN BLUE P85 VIVID PURPLE RP6 VIVID PINK BR98 CHESTNUT BROWN BR100 WALNUT CG5 COOL GREY WG5 WARM GREY R15 GERANIUM YR132 MILKY WHITE Y37 PASTEL YELLOW GY231 SEAWEED GREEN G241 GRAYISH GREEN DEEP BG251 VERONA BLUE B66 BABY BLUE PB70 ROYAL BLUE P282 -

Photo De Baby Blue

Actuator Specification & Installation Instructions Features: TM200N • Clutch for manual adjustments. TM220N • Maintenance free. TM260N TM280N • Position indicator. RM200N • Control signal fully programmable. RM220N • Brushless DC driven motor. RM260N • 1 Fail safe by Enerdrive System RM280N (on model 260 & 280). • Auxiliary switches (on model 260 & 280). Technical Data TM200N TM220N TM260N TM280N RM200N RM220N RM260N RM280N Auxiliary switches No Yes (2) No Yes (2) No Yes (2) No Yes (2) Fail safe - Enerdrive No Yes No Yes Power consumption 20 VA 45 VA Peak, 20 VA 30 VA 50 VA Peak, 30 VA Torque 180 in.lb. [20 Nm] at rated voltage 360 in.lb. [40 Nm] at rated voltage Running time 40 to 50 sec torque dependant through 90º Power supply 28 to 32 Vdc or 22 to 26 Vac, 220 to 250 Vac 50/60Hz Feedback 4 to 20 mA or 2 to 10 Vdc adjustable Electrical connection 18 AWG [0.8 mm2] minimum Inlet bushing 2 inlet bushing of 7/8 in [22.2 mm] Control signal Analog, Digital or PWM programmable (factory set with analog control signal) Angle of rotation 0 to 90 degrees, electronically adjustable (factory set with 90º stroke) Direction of rotation Reversible, Clockwise (CW) or Counterclockwise (CCW) (factory set with CW direction) Operating 0ºF to 122ºF [-18ºC to 50ºC] temperature Storage temperature -22ºF to 122ºF [-30ºC to 50ºC] Relative Humidity 5 to 95 % non condensing. Weight 5 lbs. [2.3 kg] 8 lbs. [3.5 kg] Warning: Do not press the clutch when actuator is powered Dimensions Dimension Imperial (in) Metric (mm) A 5.20 132.1 B 1.33 33.8 C 9.13 231.9 D 3.55 90.2 Caution We strongly recommend that all Neptronic® products be wired to a separate transformer and that transformer shall service only Neptronic® products. -

Air Force Blue (Raf) {\Color{Airforceblueraf}\#5D8aa8

Air Force Blue (Raf) {\color{airforceblueraf}\#5d8aa8} #5d8aa8 Air Force Blue (Usaf) {\color{airforceblueusaf}\#00308f} #00308f Air Superiority Blue {\color{airsuperiorityblue}\#72a0c1} #72a0c1 Alabama Crimson {\color{alabamacrimson}\#a32638} #a32638 Alice Blue {\color{aliceblue}\#f0f8ff} #f0f8ff Alizarin Crimson {\color{alizarincrimson}\#e32636} #e32636 Alloy Orange {\color{alloyorange}\#c46210} #c46210 Almond {\color{almond}\#efdecd} #efdecd Amaranth {\color{amaranth}\#e52b50} #e52b50 Amber {\color{amber}\#ffbf00} #ffbf00 Amber (Sae/Ece) {\color{ambersaeece}\#ff7e00} #ff7e00 American Rose {\color{americanrose}\#ff033e} #ff033e Amethyst {\color{amethyst}\#9966cc} #9966cc Android Green {\color{androidgreen}\#a4c639} #a4c639 Anti-Flash White {\color{antiflashwhite}\#f2f3f4} #f2f3f4 Antique Brass {\color{antiquebrass}\#cd9575} #cd9575 Antique Fuchsia {\color{antiquefuchsia}\#915c83} #915c83 Antique Ruby {\color{antiqueruby}\#841b2d} #841b2d Antique White {\color{antiquewhite}\#faebd7} #faebd7 Ao (English) {\color{aoenglish}\#008000} #008000 Apple Green {\color{applegreen}\#8db600} #8db600 Apricot {\color{apricot}\#fbceb1} #fbceb1 Aqua {\color{aqua}\#00ffff} #00ffff Aquamarine {\color{aquamarine}\#7fffd4} #7fffd4 Army Green {\color{armygreen}\#4b5320} #4b5320 Arsenic {\color{arsenic}\#3b444b} #3b444b Arylide Yellow {\color{arylideyellow}\#e9d66b} #e9d66b Ash Grey {\color{ashgrey}\#b2beb5} #b2beb5 Asparagus {\color{asparagus}\#87a96b} #87a96b Atomic Tangerine {\color{atomictangerine}\#ff9966} #ff9966 Auburn {\color{auburn}\#a52a2a} #a52a2a Aureolin -

On the Color Blue in Cinema

07 BLUE Léa Seydoux’s blue hair might as well be the only thing in the movie; it is responsible THE CINEMATIC for bringing the entire world into color. words eileen townsend on the silver screen, blue is for sadness, for women, for power, for sex. filmmakers use the many shades of blue to reflect the world, revealing its natural poetry and luminous complexity. Some blues wash over you: slate blue, sky blue, cornflower villain and hypnotizes the virgin. When Frank Booth (played Blue is the Warmest Color (2013) by Abdellatif Kechiche archive blue. These shades drift easily, finding the smooth surfaces by Dennis Hopper) tries to stuff Dorothy Vallens’s robe in af of things. Other blues emanate: sapphire blue, azure, Inter- his mouth, tries to consume it, it leaves him whimpering or national Klein Blue — shades that bleed and pool, that trap enraged. Blue evades him. Lynch’s blue is erotic, no doubt, light and refuse to let it go. Hypnotic blue. VCR screen blue. but it isn’t the color of a woman’s sexuality so much as it is DEPTHS OF BLUE In movies, blue is everywhere, and it’s usually a woman’s the color of a woman’s spirit, her inaccessible depths. color, despite the fact that we grew up learning that “pink is Blue movies are sad movies. Is it too obvious to say that for girls” and “blue is for boys.” Putting aside baby-blue, a grief is blue? The word has stood as a metaphor for depres- sleepy-eyed color for pouty blondes (think Christina Ricci sion for so long that it’s a cliché – “blue nights” or “blue in Vincent Gallo’s 1998 film Buffalo ’66), the true woman’s Christmas” or “having the blues.” But a certain kind of blue, blue is the deep, indescribable blue of Isabella Rossellini’s a steel blue, suggests a complicated melancholy. -

Floriani Thread Color Chart

Floriani Deluxe Thread Color Chart High Sheen 100% Polyester Thread Available in 1000M and 5000M Cones 1 Copper Black Cherry Begonia Light Pink Sangria Deep Violet PF0186 PMS 179C PF0197 PMS 195C PF1083 PMS 191C PF0102 PMS 1895C PF0139 PMS 229C PF0665 PMS 273C 2 Wildflower Old Roseleaf Shrimp Oyster Powder Puff Grape Juice PF0173 PMS 172C PF0196 PMS 506C PF1107 PMS 148C PF0100 PMS Cool Gray 1C PF0133 PMS 514C PF0696 PMS 2685 3 Burnt Orange Cabernet Grapefruit Pale Peach Roseleaf Grape Jam PF0755 PMS 166C PF1586 PMS 1815C PF0155 PMS 1925C PF0110 PMS 503C PF1902 PMS 687C PF0695 PMS 2685C 4 Orange Russet Rose Cerise Rosewater Pink Mist Tulip PF0172 PMS 165C PF0195 PMS 194C PF1082 PMS 190C PF0161 PMS 705C PF0123 PMS 2365C PF0694 PMS 2617C 5 Carrot Cherry Blush Soapstone Wisteria Amethyst PF0537 PMS 151C PF0193 PMS 194C PF0153 PMS 701C PF0163 PMS 488C PF0130 PMS 678C PF0672 PMS 2567C 6 Golden Poppy Scarlet Misty Pink Buff Bright Pink Lavender PF0535 PMS 164C PF0190 PMS 201C PF0117 PMS 701C PF1021 PMS 698C PF0125 PMS 223C PF0673 PMS 2577C 7 Bijol Burgundy Candy Pink Lace Light Lilac Light Mauve PF0526 PMS 1375C PF0194 PMS 202C PF0152 PMS 700C PF0116 PMS 496C PF0131 PMS 236C PF0674 PMS 2587C 8 Sorbet Deep Rust Champagne Light Coral Hot Pink Luxury PF0525 PMS 137C PF0192 PMS 207C PF1011 PMS 706C PF0140 PMS 169C PF0127 PMS 191C PF0675 PMS 526C 9 Apricot Hibiscus Dusty Rose Pink Rose Flamingo Royal Purple PF0533 PMS 137C PF1084 PMS 1925C PF1014 PMS 710C PF1081 PMS 707C PF0128 PMS 240C PF0676 PMS 2617C 10 Pumpkin Persimmon China Rose Pale Pink Deep