Gamification of Gothic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Serious Games to Cope with the Genetic

i “thesis_A4” — 2018/12/20 — 12:35 — page 1 — #1 i i i Dipartimento di Informatica “Giovanni Degli Antoni” Doctoral Programme in Computer Science SERIOUS GAMES TO COPE WITH THE GENETIC TEST REVOLUTION Doctoral Dissertation of: Renato Mainetti Supervisor: Prof. N.Alberto Borghese Tutor: PhD Serena Oliveri The Chair of the Doctoral Program: Prof. Paolo Boldi Year 2018 – Cycle XXXI i i i i i “thesis_A4” — 2018/12/20 — 12:35 — page 2 — #2 i i i i i i i i “thesis_A4” — 2018/12/20 — 12:35 — page 1 — #3 i i i Acknowledgements Financial support: This work is supported by the project Mind the Risk from The Swedish Foundation for Humanities and Social Sciences, which had no influence on the content of this thesis. Grant nr. M13-0260:1 1 i i i i i “thesis_A4” — 2018/12/20 — 12:35 — page 2 — #4 i i i This research was carried out under the supervision of Prof.ssa Gabriella Pravettoni and Prof. N. Alberto Borghese. I wish to thank them for the great opportunity they gave me, allowing me to be part of the Mind the Risk project. It has been a wonderful experience and I am grateful for the trust I was given in conducting my research. I wish to thank all the people involved in the MTR project, with which I had the pleasure to work and especially Serena, Ilaria and Alessandra. Many thanks also go to Silvia and Daria for the help in collecting additional data. I wish to thank all the people who helped, participating in the test experiments. -

Matheus Lima Cunha Desenvolvimento De Um Jogo Do

Universidade de São Paulo Instituto de Matemática e Estatística Bachalerado em Ciência da Computação Matheus Lima Cunha Desenvolvimento de um jogo do gênero Metroidvania com geração procedural de mapas. São Paulo Dezembro de 2020 Desenvolvimento de um jogo do gênero Metroidvania com geração procedural de mapas. Monografia final da disciplina MAC0499 – Trabalho de Formatura Supervisionado. Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Ricardo Nakamura São Paulo Dezembro de 2020 Agradecimentos Gostaria de agradecer minha família que sempre cuidou de mim e me motivou a seguir meus sonhos. Thalia Laura por me ajudar com a parte visual do jogo e, mais importante, nos momentos difíceis.Por fim, meu orientador, Ricardo Nakamura, por me orientar mesmo observando muitos outros alunos. i Resumo Neste trabalho foi desenvolvido um jogo do gênero metroidvania aplicando-se técnicas de geração procedural de conteúdo na criação do mapa. Essa ideia vêm da suposição que essas técnicas, pouco usadas em jogos do gênero, possam contribuir positivamente para a experiencia: beneficiando sensação de exploração (uma das principais características do gê- nero metroidvania) e estimulariam que o usuário os jogue novamente após ter terminado a historia. O desenvolvimento foi feito em três etapas: criação do jogo base, estudo de al- goritmos e implementação do gerador. As primeiras versões serviram para fundamentar as principais mecânicas de jogo, sem o uso de geração procedural. Após um estudo de diferen- tes algoritmos, as melhores foram implementadas no protótipo final. As avaliações indicam interesse e divertimento da maior parte dos usuários do protótipo final. Próximos passos para este trabalho incluem a melhoria do sistema de combate do jogo como também testes com diferentes algoritmos de geração. -

Discussing on Gamification for Elderly Literature, Motivation and Adherence

Discussing on Gamification for Elderly Literature, Motivation and Adherence Jose Barambones1, Ali Abavisani1, Elena Villalba-Mora1;2, Miguel Gomez-Hernandez1;3 and Xavier Ferre1 1Center for Biomedical Technology, Universidad Politecnica´ de Madrid, Spain 2Biomedical Research Networking Centre in Bioengineering Biomaterials and Nanomedicine (CIBER-BBN), Spain 3Aalborg University, Denmark Keywords: Gamification, Serious Games, Exergames, Elderly, Frailty, Discussion. Abstract: Gamification and Serious games techniques have been accepted as an effective method to strengthen the per- formance and motivation of people in education, health, entertainment, workplace and business. Concretely, exergames have been increasingly applied to raise physical activities and health or physical performance im- provement among elders. To the extend of our understanding, there is an extensive research on gamification and serious games for elderly in health. However, conducted studies assume certain issues regarding context biases, lack of applied guidelines or standardization, or weak results. We assert that a greater effort must be applied to explore and understand the needs and motivations of elderly players. Further, for improving the impact in proof-of-concept solutions and experiments some well-known guidelines or foundations must be adopted. In our current work, we are applying exergames on elderly with frailty condition in order to improve patient engagement in healthcare prevention and intervention. We suggest that to detect and reinforce such traits on elderly is adequate to extend the literature properly. 1 INTRODUCTION preserve the intrinsic capacity of the individual, its en- vironmental characteristics and their interaction. In In recent years, a rapid increase of consumer soft- parallel, by 2050 life expectancy will surpass 90 years ware inspired by the video-gaming has been per- and one in six people in the world will be over age 65 ceived. -

Nordic Game Is a Great Way to Do This

2 Igloos inc. / Carcajou Games / Triple Boris 2 Igloos is the result of a joint venture between Carcajou Games and Triple Boris. We decided to use the complementary strengths of both studios to create the best team needed to create this project. Once a Tale reimagines the classic tale Hansel & Gretel, with a twist. As you explore the magical forest you will discover that it is inhabited by many characters from other tales as well. Using real handmade puppets and real miniature terrains which are then 3D scanned to create a palpable, fantastic world, we are making an experience that blurs the line between video game and stop motion animated film. With a great story and stunning visuals, we want to create something truly special. Having just finished our prototype this spring, we have already been finalists for the Ubisoft Indie Serie and the Eidos Innovation Program. We want to validate our concept with the European market and Nordic Game is a great way to do this. We are looking for Publishers that yearn for great stories and games that have a deeper meaning. 2Dogs Games Ltd. Destiny’s Sword is a broad-appeal Living-Narrative Graphic Adventure where every choice matters. Players lead a squad of intergalactic peacekeepers, navigating the fallout of war and life under extreme circumstances, while exploring a breath-taking and immersive world of living, breathing, hand-painted artwork. Destiny’s Sword is filled with endless choices and unlimited possibilities—we’re taking interactive storytelling to new heights with our proprietary Insight Engine AI technology. This intricate psychology simulation provides every character with a diverse personality, backstory and desires, allowing them to respond and develop in an incredibly human fashion—generating remarkable player engagement and emotional investment, while ensuring that every playthrough is unique. -

Drivers and Barriers to Adopting Gamification: Teachers' Perspectives

Drivers and Barriers to Adopting Gamification: Teachers’ Perspectives Antonio Sánchez-Mena1 and José Martí-Parreño*2 1HR Manager- Universidad Europea de Valencia, Valencia, Spain and Universidad Europea de Canarias, Tenerife, Spain 2Associate Professor - Universidad Europea de Valencia, Valencia, Spain [email protected] [email protected] Abstract: Gamification is the use of game design elements in non-game contexts and it is gaining momentum in a wide range of areas including education. Despite increasing academic research exploring the use of gamification in education little is known about teachers’ main drivers and barriers to using gamification in their courses. Using a phenomenology approach, 16 online structured interviews were conducted in order to explore the main drivers that encourage teachers serving in Higher Education institutions to using gamification in their courses. The main barriers that prevent teachers from using gamification were also analysed. Four main drivers (attention-motivation, entertainment, interactivity, and easiness to learn) and four main barriers (lack of resources, students’ apathy, subject fit, and classroom dynamics) were identified. Results suggest that teachers perceive the use of gamification both as beneficial but also as a potential risk for classroom atmosphere. Managerial recommendations for managers of Higher Education institutions, limitations of the study, and future research lines are also addressed. Keywords: gamification, games and learning, drivers, barriers, teachers, Higher Education. 1. Introduction Technological developments and teaching methodologies associated with them represent new opportunities in education but also a challenge for teachers of Higher Education institutions. Teachers must face questions regarding whether to implement new teaching methodologies in their courses based on their beliefs on expected outcomes, performance, costs, and benefits. -

In This Day of 3D Graphics, What Lets a Game Like ADOM Not Only Survive

Ross Hensley STS 145 Case Study 3-18-02 Ancient Domains of Mystery and Rougelike Games The epic quest begins in the city of Terinyo. A Quake 3 deathmatch might begin with a player materializing in a complex, graphically intense 3D environment, grabbing a few powerups and weapons, and fragging another player with a shotgun. Instantly blown up by a rocket launcher, he quickly respawns. Elapsed time: 30 seconds. By contrast, a player’s first foray into the ASCII-illustrated world of Ancient Domains of Mystery (ADOM) would last a bit longer—but probably not by very much. After a complex process of character creation, the intrepid adventurer hesitantly ventures into a dark cave—only to walk into a fireball trap, killing her. But a perished ADOM character, represented by an “@” symbol, does not fare as well as one in Quake: Once killed, past saved games are erased. Instead, she joins what is no doubt a rapidly growing graveyard of failed characters. In a day when most games feature high-quality 3D graphics, intricate storylines, or both, how do games like ADOM not only survive but thrive, supporting a large and active community of fans? How can a game design seemingly premised on frustrating players through continual failure prove so successful—and so addictive? 2 The Development of the Roguelike Sub-Genre ADOM is a recent—and especially popular—example of a sub-genre of Role Playing Games (RPGs). Games of this sort are typically called “Roguelike,” after the founding game of the sub-genre, Rogue. Inspired by text adventure games like Adventure, two students at UC Santa Cruz, Michael Toy and Glenn Whichman, decided to create a graphical dungeon-delving adventure, using ASCII characters to illustrate the dungeon environments. -

The First but Hopefully Not the Last: How the Last of Us Redefines the Survival Horror Video Game Genre

The College of Wooster Open Works Senior Independent Study Theses 2018 The First But Hopefully Not the Last: How The Last Of Us Redefines the Survival Horror Video Game Genre Joseph T. Gonzales The College of Wooster, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://openworks.wooster.edu/independentstudy Part of the Other Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Other Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Gonzales, Joseph T., "The First But Hopefully Not the Last: How The Last Of Us Redefines the Survival Horror Video Game Genre" (2018). Senior Independent Study Theses. Paper 8219. This Senior Independent Study Thesis Exemplar is brought to you by Open Works, a service of The College of Wooster Libraries. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Independent Study Theses by an authorized administrator of Open Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Copyright 2018 Joseph T. Gonzales THE FIRST BUT HOPEFULLY NOT THE LAST: HOW THE LAST OF US REDEFINES THE SURVIVAL HORROR VIDEO GAME GENRE by Joseph Gonzales An Independent Study Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Course Requirements for Senior Independent Study: The Department of Communication March 7, 2018 Advisor: Dr. Ahmet Atay ABSTRACT For this study, I applied generic criticism, which looks at how a text subverts and adheres to patterns and formats in its respective genre, to analyze how The Last of Us redefined the survival horror video game genre through its narrative. Although some tropes are present in the game and are necessary to stay tonally consistent to the genre, I argued that much of the focus of the game is shifted from the typical situational horror of the monsters and violence to the overall narrative, effective dialogue, strategic use of cinematic elements, and character development throughout the course of the game. -

Sound, Embodiment, and the Experience of Interactivity in Video Games & Virtual

Sound, Embodiment, and the Experience of Interactivity in Video Games & Virtual Environments –DRAFT—citations incomplete! Lori Landay, Professor of Cultural Studies Berklee College of Music This presentation is part of a larger project that explores perception and imagination in interactive media, and how they are created by sound, image, and action. It marks an early stage in extending my previous work on the virtual kinoeye in virtual worlds and video games to consider aural, haptic, and kinetic aspects of embodiment and interactivity. SLIDE 2 2 In particular, the argument is that innovative sound has the potential to bridge the gaps in experiencing embodiment caused by disconnections between the perceived body in physical, representational, and imagined contexts. To explore this, I draw on Walter Murch’s spectrum of encoded and embodied sound, interviews with sound designers and composers, ways of thinking about the body from phenomenology, video game studies scholarship, and examples of the relationship between sound effects and music in video games. Let’s start with a question philosopher Don Ihde poses when he asks his students to imagine then describe an activity they have never done. Often students choose jumping out of an airplane with a parachute, and as he works through the distinctions between the possible senses of one’s own body as the physical body, a first-person perspective of the perceiving body, which 3 he calls the here-body, or the objectified over-there-body, the third-person view of one’s own body, he asks, “Where does one feel the wind?” Ihde argues the full multidimensional sensory experience is in the embodied perspective. -

A Systematic Review on the Effectiveness of Gamification Features in Exergames

Proceedings of the 50th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences | 2017 How Effective Is “Exergamification”? A Systematic Review on the Effectiveness of Gamification Features in Exergames Amir Matallaoui Jonna Koivisto Juho Hamari Ruediger Zarnekow Technical University of School of Information School of Information Technical University of Berlin Sciences, Sciences, Berlin amirqphj@ University of Tampere University of Tampere ruediger.zarnekow@ mailbox.tu-berlin.de [email protected] [email protected] ikm.tu-berlin.de One of the most prominent fields where Abstract gamification and other gameful approaches have been Physical activity is very important to public health implemented is the health and exercise field [7], [3]. and exergames represent one potential way to enact it. Digital games and gameful systems for exercise, The promotion of physical activity through commonly shortened as exergames, have been gamification and enhanced anticipated affect also developed extensively during the past few decades [8]. holds promise to aid in exercise adherence beyond However, due to the technological advancements more traditional educational and social cognitive allowing for more widespread and affordable use of approaches. This paper reviews empirical studies on various sensor technologies, the exergaming field has gamified systems and serious games for exercising. In been proliferating in recent years. As the ultimate goal order to gain a better understanding of these systems, of implementing the game elements to any non- this review examines the types and aims (e.g. entertainment context is most often to induce controlling body weight, enjoying indoor jogging…) of motivation towards the given behavior, similarly the the corresponding studies as well as their goal of the exergaming approaches is supporting the psychological and physical outcomes. -

Myst 3 Exile Mac Download

Myst 3 exile mac download CLICK TO DOWNLOAD Myst III: Exile Patch for Mac Free UbiSoft Entertainment Mac/OS Classic Version Full Specs The product has been discontinued by the publisher, and renuzap.podarokideal.ru offers this page for Subcategory: Sudoku, Crossword & Puzzle Games. The latest version of Myst III is on Mac Informer. It is a perfect match for the General category. The app is developed by Myst III renuzap.podarokideal.ruin. Myst III: Exile X for Mac Free Download. MB Mac OS X About Myst III: Exile X for Mac. The all NEW sequel to Myst and Riven new technology, new story and a new arch enemy. It's the perfect place to plan revenge. The success of Myst continues with 5 entirely new ages to explore and a dramatic new storyline, which features a pivotal new character. This version is the first release on CNET /5. Myst III (3): Exile (Mac abandonware from ) Myst III (3): Exile. Author: Presto Studios. Publisher: UbiSoft. Type: Games. Category: Adventure. Shared by: MR. On: Updated by: that-ben. On: Rating: out of 10 (0 vote) Rate it: WatchList. ; 3; 0 (There's no video for Myst III (3): Exile yet. Please contribute to MR and add a video now!) What is . myst exile free download - Myst III: Exile X, Myst III: Exile Patch, Myst IV Revelation Patch, and many more programs. 01/07/ · Myst III Exile DVD Edition - Windows-Mac (Eng) Item Preview Myst III Exile DVD Edition - renuzap.podarokideal.ru DOWNLOAD OPTIONS download 1 file. ITEM TILE download. download 1 file. -

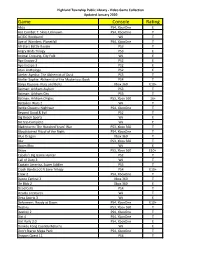

Game Console Rating

Highland Township Public Library - Video Game Collection Updated January 2020 Game Console Rating Abzu PS4, XboxOne E Ace Combat 7: Skies Unknown PS4, XboxOne T AC/DC Rockband Wii T Age of Wonders: Planetfall PS4, XboxOne T All-Stars Battle Royale PS3 T Angry Birds Trilogy PS3 E Animal Crossing, City Folk Wii E Ape Escape 2 PS2 E Ape Escape 3 PS2 E Atari Anthology PS2 E Atelier Ayesha: The Alchemist of Dusk PS3 T Atelier Sophie: Alchemist of the Mysterious Book PS4 T Banjo Kazooie- Nuts and Bolts Xbox 360 E10+ Batman: Arkham Asylum PS3 T Batman: Arkham City PS3 T Batman: Arkham Origins PS3, Xbox 360 16+ Battalion Wars 2 Wii T Battle Chasers: Nightwar PS4, XboxOne T Beyond Good & Evil PS2 T Big Beach Sports Wii E Bit Trip Complete Wii E Bladestorm: The Hundred Years' War PS3, Xbox 360 T Bloodstained Ritual of the Night PS4, XboxOne T Blue Dragon Xbox 360 T Blur PS3, Xbox 360 T Boom Blox Wii E Brave PS3, Xbox 360 E10+ Cabela's Big Game Hunter PS2 T Call of Duty 3 Wii T Captain America, Super Soldier PS3 T Crash Bandicoot N Sane Trilogy PS4 E10+ Crew 2 PS4, XboxOne T Dance Central 3 Xbox 360 T De Blob 2 Xbox 360 E Dead Cells PS4 T Deadly Creatures Wii T Deca Sports 3 Wii E Deformers: Ready at Dawn PS4, XboxOne E10+ Destiny PS3, Xbox 360 T Destiny 2 PS4, XboxOne T Dirt 4 PS4, XboxOne T Dirt Rally 2.0 PS4, XboxOne E Donkey Kong Country Returns Wii E Don't Starve Mega Pack PS4, XboxOne T Dragon Quest 11 PS4 T Highland Township Public Library - Video Game Collection Updated January 2020 Game Console Rating Dragon Quest Builders PS4 E10+ Dragon -

An Interactive Non-Linear Adventure

Rochester Institute of Technology RIT Scholar Works Theses 12-6-1994 Live it! - An Interactive non-linear adventure Gedeon Maheux Talos Tsui Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.rit.edu/theses Recommended Citation Maheux, Gedeon and Tsui, Talos, "Live it! - An Interactive non-linear adventure" (1994). Thesis. Rochester Institute of Technology. Accessed from This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by RIT Scholar Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of RIT Scholar Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rochester Institute of Technology A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The College of Imaging Arts and Sciences in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Fine Arts Live It! - An Interactive Non-Linear Adventure by Gedeon Maheux & Talos, Shu-Ming, Tsui December 6, 1994 Committee Sipnatures Thesis Approval ,James VerHague Date: /.2. ~ ~ ~ 't 'f chief adviser Deborah Beardslee Date: :1 &amkv'lf associate adviser (2. - Robert Keough Date: ('-1L( associate adviser Nancy Ciolek Date: / 2 - b -9if associate adviser David Abbott Date: /2- -1- >if associate adviser Mary ANn Begland Date: /2. - 7· 91 Department Chairperson Gedeon Maheux Date: _ MFA Candidate Talos, Shu-Ming, Tsui Date: _ MFA Candidate We. & hereby grant permission to the Wallace Memorial Library of RIT to reproduce our thesis in whole or in part. Any reproduction will not be for commercial use or profit. Acknowledgements We would like to thank our parents for their support,