Little Golden Bookstm: an Analysis of Every Child's Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

293-8788 [email protected] RAINBOW BRITE HEADS to TOYS

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: Ilona Zaks United Media (212) 293-8788 [email protected] RAINBOW BRITE HEADS TO TOYS ‘R US WITH AN EXCLUSIVE LINE FROM PLAYMATES TOYS Fashion Dolls and Horses To Roll Out In Time For Holiday 2009 New York (June 2, 2009) -- Rainbow Brite’s master toy licensee Playmates Toys will be unveiling its much anticipated line of a contemporized fashion dolls and horses exclusively at Toys R’ Us in time for holiday 2009, honoring the nostalgic look, indomitable spirit and energy that Rainbow Brite embodies with a trendy tween redesign that girls will adore. Rainbow Brite plush, small dolls, large dolls, and play sets will follow at other select retailers in 2010. United Media, a leading independent licensing and syndication company, has been working with long- time partner Hallmark to build a licensing program in support of Rainbow Brite. Introduced by Hallmark Cards as an animated television series in 1984, the Rainbow Brite franchise generated $1 billion in retail sales of dolls, toys and other licensed products. Empowering a new generation of girls to spread hope and happiness, a new innovative program launch is underway featuring Rainbow and her best friends Tickled Pink and Moonglow. Rainbow Brite marks the third addition to the United Media and Hallmark licensing relationship, which also includes the popular hoops&yoyo and Maxine brands. Playmates Toys and Hallmark will support the Rainbow Brite product launch with character content online and in-pack and through the “Share A Rainbow” challenge, an inspiring socially-conscious program that taps kids’ desire to “help” and encourages girls to channel their energies into creating a better world. -

Batman Miniature Game Teams

TEAMS IN Gotham MAY 2020 v1.2 Teams represent an exciting new addition to the Batman Miniature Game, and are a way of creating themed crews that represent the more famous (and infamous) groups of heroes and villains in the DC universe. Teams are custom crews that are created using their own rules instead of those found in the Configuring Your Crew section of the Batman Miniature Game rulebook. In addition, Teams have some unique special rules, like exclusive Strategies, Equipment or characters to hire. CONFIGURING A TEAM First, you must choose which team you wish to create. On the following pages, you will find rules for several new teams: the Suicide Squad, Bat-Family, The Society, and Team Arrow. Models from a team often don’t have a particular affiliation, or don’t seem to have affiliations that work with other members, but don’t worry! The following guidelines, combined with the list of playable characters in appropriate Recruitment Tables, will make it clear which models you may include in your custom crew. Once you have chosen your team, use the following rules to configure it: • You must select a model to be the Team’s Boss. This model doesn’t need to have the Leader or Sidekick Rank – s/he can also be a Free Agent. See your team’s Recruitment Table for the full list of characters who can be recruited as your team’s Boss. • Who is the Boss in a Team? 1. If there is a model with Boss? Always present, they MUST be the Boss, regardless of a rank. -

BERNARD BAILY Vol

Roy Thomas’ Star-Bedecked $ Comics Fanzine JUST WHEN YOU THOUGHT 8.95 YOU KNEW EVERYTHING THERE In the USA WAS TO KNOW ABOUT THE No.109 May JUSTICE 2012 SOCIETY ofAMERICA!™ 5 0 5 3 6 7 7 2 8 5 Art © DC Comics; Justice Society of America TM & © 2012 DC Comics. Plus: SPECTRE & HOUR-MAN 6 2 8 Co-Creator 1 BERNARD BAILY Vol. 3, No. 109 / April 2012 Editor Roy Thomas Associate Editors Bill Schelly Jim Amash Design & Layout Jon B. Cooke Consulting Editor John Morrow FCA Editor P.C. Hamerlinck AT LAST! Comic Crypt Editor ALL IN Michael T. Gilbert Editorial Honor Roll COLOR FOR $8.95! Jerry G. Bails (founder) Ronn Foss, Biljo White Mike Friedrich Proofreader Rob Smentek Cover Artist Contents George Pérez Writer/Editorial: An All-Star Cast—Of Mind. 2 Cover Colorist Bernard Baily: The Early Years . 3 Tom Ziuko With Special Thanks to: Ken Quattro examines the career of the artist who co-created The Spectre and Hour-Man. “Fairytales Can Come True…” . 17 Rob Allen Roger Hill The Roy Thomas/Michael Bair 1980s JSA retro-series that didn’t quite happen! Heidi Amash Allan Holtz Dave Armstrong Carmine Infantino What If All-Star Comics Had Sported A Variant Line-up? . 25 Amy Baily William B. Jones, Jr. Eugene Baily Jim Kealy Hurricane Heeran imagines different 1940s JSA memberships—and rivals! Jill Baily Kirk Kimball “Will” Power. 33 Regina Baily Paul Levitz Stephen Baily Mark Lewis Pages from that legendary “lost” Golden Age JSA epic—in color for the first time ever! Michael Bair Bob Lubbers “I Absolutely Love What I’m Doing!” . -

Treasure Hunt Doll Auction Friday March 28, 2014 Starting 9:00 AM

Treasure Hunt Doll Auction Friday March 28, 2014 Starting 9:00 AM Friday Selling Times Large Gallery Room Gallery Session 9:00 AM- Treasure Hunt Dolls Item # 1001- 1618 (Green stickers) Terms and Conditions of Auction: 1. Payment: cash, certified check or personal check if known to the auctioneers. Visa, MC, Discover accepted. 15 % buyers premium. 5% discount for cash or check payment. Cash only payment may be specified for individual bidders at auctioneers request. 2. We have endeavored to describe all items to the best of our ability - however, this is not a warranty. All items are sold as is. The auctioneer has the right to make any verbal corrections at time of sale and to provide additional information. Inspection is welcomed during preview and anytime before the item is sold. 3. In case of disputed bid the auctioneer has the authority to settle disputes to the best of his ability and his decision is final. 4. The auctioneer has the right to reject any raise not commensurate with the value of the item being offered. Items are sold without reserve, unless advertised otherwise, except in the case of jewelry, gold, silver and currency. Jewelry and coins require an opening bid of 90 % of scrap value. Jewelry items with appraisals require an opening bid of 10% of appraised value. Currency must be 10 % over face value. 5. All sales are final and all items must be paid for each day of sale. A moving and storage fee may be assessed for items not picked up within 3 business days after auction. -

Great Fashion Designs of the Nineties - Paper Dolls Free Download

GREAT FASHION DESIGNS OF THE NINETIES - PAPER DOLLS FREE DOWNLOAD Tom Tierney | 32 pages | 01 Feb 2001 | Dover Publications Inc. | 9780486413310 | English | New York, United States 13 Dolls From The '90s You Totally Forgot About The line did not take off immediately when it was introduced in Add to Watchlist Unwatch. This doll inspired her to come up with the concept of an adult fashion doll who we now all know as the iconic doll and media franchise Barbie, a name given to her as a reference to Handler's daughter, Barbara. He was the designer to iconic public figures, celebrities, and even royalty, most notably Princess Diana. No obvious damage to the cover, with the Great Fashion Designs of the Nineties - Paper Dolls jacket if applicable included for hard covers. And her models did not wear stiletto heels on the runway. It came out in and came with a fur-trimmed outfit that could match a Ski Fun Barbie absolutely perfectly. And hey, remember that My Little Pony connection? For additional information, see the Global Shipping Program terms and conditions - opens in a new window or tab. Learn more - eBay Money Back Guarantee - opens in new window or tab. The real detail in this Barbie comes from the fact that silk roses in different sizes cover her skirt. He grabbed the attention of many with his first fashion house inshowcasing clothes with unique combinations of colors and patterns. Between all the detail in the Barbie and her accessories, like the glass beads and the gorgeous feathered hat, and the fact that it Great Fashion Designs of the Nineties - Paper Dolls released as a limited edition doll, we're not surprised that it's so expensive now! Barbies have been released for many different seasons and holidays, but this winter Barbie is definitely one of the more sought out ones Great Fashion Designs of the Nineties - Paper Dolls collectors who love Barbie dolls. -

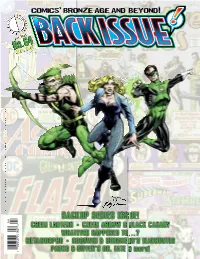

Backup Series Issue! 0 8 Green Lantern • Green Arrow & Black Canary 2 6 7 7

0 4 No.64 May 201 3 $ 8 . 9 5 1 82658 27762 8 METAMORPHO • GOODWIN & SIMONSON’S MANHUNTER GREEN LANTERN • GREEN ARROW & BLACK CANARY COMiCs PASKO & GIFFEN’S DR. FATE & more! , WHATEVER HAPPENED TO…? BACKUP SERIES ISSUE! bROnzE AGE AnD bEYOnD i . Volume 1, Number 64 May 2013 Celebrating the Best Comics of Comics’ Bronze Age and Beyond! the '70s, '80s, '90s, and Beyond! EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Michael Eury PUBLISHER John Morrow DESIGNER Rich Fowlks COVER ARTISTS Mike Grell and Josef Rubinstein COVER COLORIST Glenn Whitmore COVER DESIGNER Michael Kronenberg BACK SEAT DRIVER: Editorial by Michael Eury . .2 PROOFREADER Rob Smentek FLASHBACK: The Emerald Backups . .3 Green Lantern’s demotion to a Flash backup and gradual return to his own title SPECIAL THANKS Jack Abramowitz Robert Greenberger FLASHBACK: The Ballad of Ollie and Dinah . .10 Marc Andreyko Karl Heitmueller Green Arrow and Black Canary’s Bronze Age romance and adventures Roger Ash Heritage Comics Jason Bard Auctions INTERVIEW: John Calnan discusses Metamorpho in Action Comics . .22 Mike W. Barr James Kingman The Fab Freak of 1001-and-1 Changes returns! With loads of Calnan art Cary Bates Paul Levitz BEYOND CAPES: A Rose by Any Other Name … Would be Thorn . .28 Alex Boney Alan Light In the back pages of Lois Lane—of all places!—sprang the inventive Rose and the Thorn Kelly Borkert Elliot S! Maggin Rich Buckler Donna Olmstead FLASHBACK: Seven Soldiers of Victory: Lost in Time Again . .33 Cary Burkett Dennis O’Neil This Bronze Age backup serial was written during the Golden Age Mike Burkey John Ostrander John Calnan Mike Royer BEYOND CAPES: The Master Crime-File of Jason Bard . -

The Metacomics of Alan Moore, Neil Gaiman, and Warren Ellis

University of Alberta Telling Stories About Storytelling: The Metacomics of Alan Moore, Neil Gaiman, and Warren Ellis by Orion Ussner Kidder A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Department of English and Film Studies ©Orion Ussner Kidder Spring 2010 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l’édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-60022-1 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-60022-1 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L’auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l’Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. -

Tag Sale Sign

.-.rf - » - > ■> » M - MANCHESTER HERALD. Friday. May 16. 1966 S P O K 1 S TAG SALE SIGN Mariners handle A borrow show Are things piling up? Then why not hsve s TAG SALE? Yankees easily at the Parkade The host way to announce it is with a Heraid Tag Sate ... page 11 ... m a g a z in e in s id e Ctasstfted Ad. When you ptace your ad, you'tt receive ONE TAG SALE SIGN FREE, compliments of The Herald. STOP IN AT OUR OFFICE, 1 HERALD SQUARE. MANCHESTER KIT *N’ CARLYLE ®by Larry Wright MUSICAL H rralh ITEMS TA6 SALES mulmtnManchpsler - A City o( U illap Charm For Solo Sterling Upright CANIW^AWNTI i w Plano. Asking $150. Coll between 5:30 and 9:30pm CxO cusm VOOP- at 643-1095. __________ Tag Sole-Saturdoy May HTT6R. W. Saturday, May 17,1986 25 Cents 17th, 10-4, 97 Bridge St., 4^^ IPETSANO (Off Wetherall St.) Man m ic M U IG A lE chester. Rain or Shine. SUPPUES Expgrianoad adult wHI do Oumoe Hoctrte->~«tavlnf Oallyerlng^cieah^faf^ )SA Electrical Rrohlems? lodm;jiyardb«75glutlaK. ,1m Manchester High School full and port tima summar D eath Good Homes needed 2 bobyslttlna. maoit and Need g.loriBa or oi sjmdl Mock & white kittens, 6 Tog Sole. May 17, 9om- RegeIrT wg Sgoetiwai in School bomb snacks providod. Roaso* weeks, very friendly, 3pm. Spaces available. ncdila rates, coll 647-70S1, Rosidarttlat W o ^ dasaptl III iiMiaWiFiisipirn ....nail .... ' ;F****iipw trolned 447-9357. Coll 647-9504 or 643-0319. Dumas. Fully Lfeansed. -

Printer Emulator for Testing

INSIDE THIS ROOM . ____________ A Master’s Exhibition of Mixed Medium Presented to the Faculty of California State University, Chico ____________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Fine Arts in Art ____________ by Erin Kelly Spring 2012 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The body of work included in my culminating thesis exhibition was made with the support and guidance of my committee, chaired by Eileen MacDonald, Nanette Wylde, and graduate coordinator Cameron Crawford. I'd also like to extend a thank you to my family for their support as well. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE Acknowledgements.................................................................................................... iii List of Figures............................................................................................................ v Abstract...................................................................................................................... vii INSIDE THIS ROOM . Introduction................................................................................................. 1 Content and Methods .................................................................................. 2 Audio.................................................................................................. 2 Prints .................................................................................................. 3 Photography ....................................................................................... 4 Books ................................................................................................ -

Guantanamo Gazette

Guantanamo Gazette Vol. 43 -- No. 243 -- U.S. Navy's only shore-based daily newspaper -- Monday, December 21, 1987 /N Local divers relieved MCX air compressor is back on-line W E Bay News By JOSH J.D. Parks "With the compressor being used so be conducted in January to determine heavily, the circuit didn't work, the need for an equipment update for Recreational divers around the allowing the filters in the system the MCX. base breathed a sigh of relief with to burn-up and contaminate four He said, "Friday, Jan. 15, a the Instruction revised word that the Marine Corps tanks." study will be conducted, and if a Exchange (MCX) compressor was back According to Bueno, some new rules need is determined, we will add a The Emergency Procedures on-line. are in effect for use of the com- new compressor, and two 3,500 Instruction, COMNAVBASEGTMOINST The wait lasted nearly a month, pressor to insure that it keeps pounds-per-square-inch (psi) holding 3050.4E, has been revised. with all the recreational canpres- working. tanks, and will be able to fill more Designated hurricane shelters sors shut down. First, there are specific hours tanks during the day." have been changed. Housing According to 1st Lt. Leo Bueno, that it can operate. It will begin Bueno added, "Until then, divers MCX Officer in occupants must come to the Charge, the breakdown operating at 9:30 a.m., and close- will have to bear with us, and housing office to pick up a copy was caused by running the compressor down at 11:30 a.m., then the hopefully these new guidelines will too of this instruction from 8:30 heavily, causing a filter con- compressor will be back in use at 2 keep the compressor operating for a a.m. -

CUCKFIELD MUSEUM Loan Boxes

CUCKFIELD MUSEUM Loan Boxes - Contents 1 Victorian toys 2 50s/60s Toys (‘toys our grandparents played with’) 3 70s/80s toys (‘toys our parents played with’) 3b 70s/80s toys continued 4 Party Time 5 Kitchenalia 6 Victorian School 7 WWII: Evacuees 8 WWII: Blitz 9 WWII: Shelter 10 Dinosaurs and Fossils Posters 1 World War II Posters 2 Post war Britain Posters 3 The Royal Family 1930s-1950s Garments Victorian Garments Swinging 60s Books Books Fees: £5 per box / collection per half term + £10 per box / collection security deposit (to be refunded on safe return of all items) To make a reservation: Contact the Museum either via [email protected] or by phoning us on 01444-473630 Loan Box 1 - Replica Victorian Toys Contents: Layer 1 (Bottom) • 4 cup and ball toys (1 large, 1 medium, 2 small) • 2 pop guns Layer 2 • 1 skipping rope (with original bobbin handles) • 3 whips (with original distaff handles) • 3 tops Layer 3 • 1 box “PickUpSticks” • 2 packs Five Stones • 1 Jacob’s Ladder • 2 Flick books (not very Victorian, but they do work, and might encourage children to make their own!) • 2 packs Victorian “Happy Families” Layer 4 • 3 Yo-Yos 3 Diablos Layer 5 (Top) • Teacher’s Resource book “Children in Victorian Times” (1) • Game instructions (4) Supplementary box • 2 metal hoops and sticks (with instructions) Loan Box 2 - Toys of the 1950s and 60s Contents: Layer 1 (Bottom) • Jigsaw: “Queen Mary Boat Train leaving Southampton” (with photo) (NB. 5 pieces missing, one piece broken) Layer 2 • Pocket Chess and Checkers /Draughts Set (no pieces -

2News Summer 05 Catalog

$ 8 . 9 5 Dr. Strange and Clea TM & © Marvel Characters, Inc. All Rights Reserved. No.71 Apri l 2014 0 3 1 82658 27762 8 Marvel Premiere Marvel • Premiere Marvel Spotlight • Showcase • 1st Issue Special Showcase • & New more! Talent TRYOUTS, ONE-SHOTS, & ONE-HIT WONDERS! Featuring BRUNNER • COLAN • ENGLEHART • PLOOG • TRIMPE COMICS’ BRONZE AGE AND COMICS’ BRONZE AGE BEYOND! Volume 1, Number 71 April 2014 Celebrating the Best Comics of the '70s, '80s, Comics’ Bronze Age and Beyond! '90s, and Beyond! EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Michael Eury PUBLISHER John Morrow DESIGNER Rich Fowlks COVER ARTIST Arthur Adams (art from the collection of David Mandel) COVER COLORIST ONE-HIT WONDERS: The Bat-Squad . .2 Glenn Whitmore Batman’s small band of British helpers were seen in a single Brave and Bold issue COVER DESIGNER ONE-HIT WONDERS: The Crusader . .4 Michael Kronenberg Hopefully you didn’t grow too attached to the guest hero in Aquaman #56 PROOFREADER Rob Smentek FLASHBACK: Ready for the Marvel Spotlight . .6 Creators galore look back at the series that launched several important concepts SPECIAL THANKS Jack Abramowitz David Kirkpatrick FLASHBACK: Marvel Feature . .14 Arthur Adams Todd Klein Mark Arnold David Anthony Kraft Home to the Defenders, Ant-Man, and Thing team-ups Michael Aushenker Paul Kupperberg Frank Balas Paul Levitz FLASHBACK: Marvel Premiere . .19 Chris Brennaman Steve Lightle A round-up of familiar, freaky, and failed features, with numerous creator anecdotes Norm Breyfogle Dave Lillard Eliot R. Brown David Mandel FLASHBACK: Strange Tales . .33 Cary Burkett Kelvin Mao Jarrod Buttery Marvel Comics The disposable heroes and throwaway characters of Marvel’s weirdest tryout book Nick Cardy David Michelinie Dewey Cassell Allen Milgrom BEYOND CAPES: 221B at DC: Sherlock Holmes at DC Comics .