Is E-Democracy More Than Democratic? - an Examination of the Implementation of Socially Sustainable Values in E-Democratic Processes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dahl and Charles E

PLEASE READ BEFORE PRINTING! PRINTING AND VIEWING ELECTRONIC RESERVES Printing tips: ▪ To reduce printing errors, check the “Print as Image” box, under the “Advanced” printing options. ▪ To print, select the “printer” button on the Acrobat Reader toolbar. DO NOT print using “File>Print…” in the browser menu. ▪ If an article has multiple parts, print out only one part at a time. ▪ If you experience difficulty printing, come to the Reserve desk at the Main or Science Library. Please provide the location, the course and document being accessed, the time, and a description of the problem or error message. ▪ For patrons off campus, please email or call with the information above: Main Library: [email protected] or 706-542-3256 Science Library: [email protected] or 706-542-4535 Viewing tips: ▪ The image may take a moment to load. Please scroll down or use the page down arrow keys to begin viewing this document. ▪ Use the “zoom” function to increase the size and legibility of the document on the screen. The “zoom” function is accessed by selecting the “magnifying glass” button on the Acrobat Reader toolbar. NOTICE CONCERNING COPYRIGHT The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproduction of copyrighted material. Section 107, the “Fair Use” clause of this law, states that under certain conditions one may reproduce copyrighted material for criticism, comment, teaching and classroom use, scholarship, or research without violating the copyright of this material. Such use must be non-commercial in nature and must not impact the market for or value of the copyrighted work. -

Measuring Polyarchy Across the Globe, 1900–2017

St Comp Int Dev https://doi.org/10.1007/s12116-018-9268-z Measuring Polyarchy Across the Globe, 1900–2017 Jan Teorell1 & Michael Coppedge2 & Staffan Lindberg3 & Svend-Erik Skaaning 4 # The Author(s) 2018 Abstract This paper presents a new measure polyarchy for a global sample of 182 countries from 1900 to 2017 based on the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) data, deriving from an expert survey of more than 3000 country experts from around the world, with on average 5 experts rating each indicator. By measuring the five compo- nents of Elected Officials, Clean Elections, Associational Autonomy, Inclusive Citi- zenship, and Freedom of Expression and Alternative Sources of Information separately, we anchor this new index directly in Dahl’s(1971) extremely influential theoretical framework. The paper describes how the five polyarchy components were measured and provides the rationale for how to aggregate them to the polyarchy scale. We find Previous versions of this paper were presented at the APSA Annual Meeting in Washington, DC, August 28- 31, 2014, at the Carlos III-Juan March Institute of Social Sciences, Madrid, November 28, 2014, and at the European University Institute, Fiesole, January 20, 2016. Any remaining omissions are the sole responsibility of the authors. Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (https://doi.org/10.1007/s12116-018- 9268-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users. * Jan Teorell [email protected] Michael Coppedge [email protected] Staffan Lindberg [email protected] -

Rethinking Populism: Peak Democracy, Liquid Identity and The

European Journal of Social Theory 1–21 ª The Author(s) 2018 Rethinking Populism: Reprints and permission: sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav Peak democracy, liquid DOI: 10.1177/1368431017754057 identity and the performance journals.sagepub.com/home/est of sovereignty Ingolfur Blu¨hdorn WU Vienna University of Economics and Business, Vienna, Austria Felix Butzlaff WU Vienna University of Economics and Business, Vienna, Austria Abstract Despite the burgeoning literature on right-wing populism, there is still considerable uncertainty about its causes, its impact on liberal democracies and about promising counter-strategies. Inspired by recent suggestions that (1) the emancipatory left has made a significant contribution to the proliferation of the populist right; and (2) populist movements, rather than challenging the established socio-political order, in fact stabilize and further entrench its logic, this article argues that an adequate understanding of the populist phenomenon necessitates a radical shift of perspective: beyond the democratic and emancipatory norms, which still govern most of the relevant literature. Approaching its subject matter via democratic theory and modernization theory, it undertakes a reassessment of the triangular relationship between modernity, democracy and popu- lism. It finds that the latter is not helpfully conceptualized as anti-modernist or anti- democratic but should, instead, be regarded as a predictable feature of the form of politics distinctive of today’s third modernity. Keywords liquid identity, peak democracy, politics of exclusion, second-order emancipation, simulative politics, third modernity Corresponding author: Ingolfur Blu¨hdorn, WU Vienna University of Economics and Business, Welthandelsplatz 1, Vienna 1020, Austria. Email: [email protected] 2 European Journal of Social Theory XX(X) Towards a shift of perspective The ongoing tide of right-wing populism rapidly and profoundly is remoulding the political culture of Western liberal democracies. -

Rethinking Populism: Peak Democracy, Liquid

Article European Journal of Social Theory 2019, Vol. 22(2) 191–211 Rethinking Populism: ª The Author(s) 2018 Peak democracy, liquid Article reuse guidelines: sagepub.com/journals-permissions DOI: 10.1177/1368431017754057 identity and the performance journals.sagepub.com/home/est of sovereignty Ingolfur Blu¨hdorn WU Vienna University of Economics and Business, Vienna, Austria Felix Butzlaff WU Vienna University of Economics and Business, Vienna, Austria Abstract Despite the burgeoning literature on right-wing populism, there is still considerable uncertainty about its causes, its impact on liberal democracies and about promising counter-strategies. Inspired by recent suggestions that (1) the emancipatory left has made a significant contribution to the proliferation of the populist right; and (2) populist movements, rather than challenging the established socio-political order, in fact stabilize and further entrench its logic, this article argues that an adequate understanding of the populist phenomenon necessitates a radical shift of perspective: beyond the democratic and emancipatory norms, which still govern most of the relevant literature. Approaching its subject matter via democratic theory and modernization theory, it undertakes a reassessment of the triangular relationship between modernity, democracy and popu- lism. It finds that the latter is not helpfully conceptualized as anti-modernist or anti- democratic but should, instead, be regarded as a predictable feature of the form of politics distinctive of today’s third modernity. Keywords liquid identity, peak democracy, politics of exclusion, second-order emancipation, simulative politics, third modernity Corresponding author: Ingolfur Blu¨hdorn, WU Vienna University of Economics and Business, Welthandelsplatz 1, Vienna 1020, Austria. Email: [email protected] 192 European Journal of Social Theory 22(2) Towards a shift of perspective The ongoing tide of right-wing populism rapidly and profoundly is remoulding the political culture of Western liberal democracies. -

Bright Mirror: How Latin America Is Enhancing Digital Democracy by Cecilia Nicolini and Matías Bianchi

All views expressed in the Latin America Policy Journal are those of the authors or the interviewees only and do not represent the views of Harvard University, the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University, the staff of the Latin America Policy Journal, or any associates of the Journal. All errors are authors’ responsibilities. © 2018 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College. All rights reserved. Except as otherwise specified, no article or portion herein is to be reproduced or adapted to other works without the expressed written consent of the editors of the Latin America Policy Journal. Bright Mirror: How Latin America is Enhancing Digital Democracy by Cecilia Nicolini and Matías Bianchi Abstract Digital Democracy has emerged as a phenomenon that aims to transform the entire relation between state and society, potentially being able to fix the current crisis of liberal democracies. Despite the fact that reality is showing that we are far from that technological panacea, many government and social movements are using those tools to empower marginalized actors, to make governments more transparent and accountable, and to make policies more participa- tory. This article unpacks the opportunities and challenges digital democracy has to offer, and reviews specific cases from Latin America in which these tools are being used for improving the quality of democracies. Introduction Digital Democracy Our democracies are outdated. In the In his famous book Polyarchy, Robert Dahl second decade of the 21st century, gov- describes democracy as “the continued ernments seem unable to address the responsiveness of the government to the complex challenges the world is facing, preferences of its citizens, considered as and citizens’ trust in public institutions political equals.”1 Today, we have the tech- is at the lowest point in decades. -

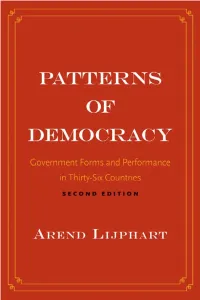

Patterns of Democracy This Page Intentionally Left Blank PATTERNS of DEMOCRACY

Patterns of Democracy This page intentionally left blank PATTERNS OF DEMOCRACY Government Forms and Performance in Thirty-Six Countries SECOND EDITION AREND LIJPHART First edition 1999. Second edition 2012. Copyright © 1999, 2012 by Arend Lijphart. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the US Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail [email protected] (US offi ce) or [email protected] (UK offi ce). Set in Melior type by Integrated Publishing Solutions, Grand Rapids, Michigan. Printed in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lijphart, Arend. Patterns of democracy : government forms and performance in thirty-six countries / Arend Lijphart. — 2nd ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-300-17202-7 (paperbound : alk. paper) 1. Democracy. 2. Comparative government. I. Title. JC421.L542 2012 320.3—dc23 2012000704 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48–1992 (Permanence of Paper). 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 for Gisela and for our grandchildren, Connor, Aidan, Arel, Caio, Senta, and Dorian, in the hope that the twenty-fi rst century—their century—will yet become more -

Democratic Culture and Muslim Political Participation in Post-Suharto Indonesia

RELIGIOUS DEMOCRATS: DEMOCRATIC CULTURE AND MUSLIM POLITICAL PARTICIPATION IN POST-SUHARTO INDONESIA DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science at The Ohio State University by Saiful Mujani, MA ***** The Ohio State University 2003 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor R. William Liddle, Adviser Professor Bradley M. Richardson Professor Goldie Shabad ___________________________ Adviser Department of Political Science ABSTRACT Most theories about the negative relationship between Islam and democracy rely on an interpretation of the Islamic political tradition. More positive accounts are also anchored in the same tradition, interpreted in a different way. While some scholarship relies on more empirical observation and analysis, there is no single work which systematically demonstrates the relationship between Islam and democracy. This study is an attempt to fill this gap by defining Islam empirically in terms of several components and democracy in terms of the components of democratic culture— social capital, political tolerance, political engagement, political trust, and support for the democratic system—and political participation. The theories which assert that Islam is inimical to democracy are tested by examining the extent to which the Islamic and democratic components are negatively associated. Indonesia was selected for this research as it is the most populous Muslim country in the world, with considerable variation among Muslims in belief and practice. Two national mass surveys were conducted in 2001 and 2002. This study found that Islam defined by two sets of rituals, the networks of Islamic civic engagement, Islamic social identity, and Islamist political orientations (Islamism) does not have a negative association with the components of democracy. -

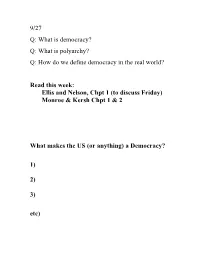

What Is Polyarchy? Q: How Do We Define Democracy in the Real World?

9/27 Q: What is democracy? Q: What is polyarchy? Q: How do we define democracy in the real world? Read this week: Ellis and Nelson, Chpt 1 (to discuss Friday) Monroe & Kersh Chpt 1 & 2 What makes the US (or anything) a Democracy? 1) 2) 3) etc) What makes the US (or anything) NOT a Democracy? 1) 2) 3) etc) I. Democratic Government A. What makes mass politics democratic? as opposed to: authoritarian / autocracy monarchy oligarchy republic etc. Traits of an “Ideal,” or pure Democracy: public opinion -> public policy 1. “Majority Rule” • 50% + 1 • full participation required 2. Public Discourse / Deliberation • perfect information • people seek out info on politics • full public discussion • full consideration of alternatives • people are interested 3. Perfect competition of groups/ideas • free entry into arena Is this "democracy"? What is left out of this definition? 1. ?? 2. ?? B. Can there ever be a perfect democracy? How do we know if/when a nation is democratic? In the real world: 1. Most people don’t vote 2. Most of us have little information about politics other things more important in daily life (job, bills, sports, love, sex, family, .......etc.) 3. People act on basis of emotion and reason 4. Institutions constrain choices • number of parties function of rules • market forces constrain media output So, what is a democracy? o In pure form, an ideal (utopia?) o In practice Q: How do we define democracy in the real world? Q: What is a republic (vs. a democracy)? “Ideal” view of Democracy something no real place can meet What real world criteria to define democracy? II. -

![Constitutionalism and the Separation of Powers [1967]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3308/constitutionalism-and-the-separation-of-powers-1967-2463308.webp)

Constitutionalism and the Separation of Powers [1967]

The Online Library of Liberty A Project Of Liberty Fund, Inc. M.J.C. Vile, Constitutionalism and the Separation of Powers [1967] The Online Library Of Liberty This E-Book (PDF format) is published by Liberty Fund, Inc., a private, non-profit, educational foundation established in 1960 to encourage study of the ideal of a society of free and responsible individuals. 2010 was the 50th anniversary year of the founding of Liberty Fund. It is part of the Online Library of Liberty web site http://oll.libertyfund.org, which was established in 2004 in order to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. To find out more about the author or title, to use the site's powerful search engine, to see other titles in other formats (HTML, facsimile PDF), or to make use of the hundreds of essays, educational aids, and study guides, please visit the OLL web site. This title is also part of the Portable Library of Liberty DVD which contains over 1,000 books and quotes about liberty and power, and is available free of charge upon request. The cuneiform inscription that appears in the logo and serves as a design element in all Liberty Fund books and web sites is the earliest-known written appearance of the word “freedom” (amagi), or “liberty.” It is taken from a clay document written about 2300 B.C. in the Sumerian city-state of Lagash, in present day Iraq. To find out more about Liberty Fund, Inc., or the Online Library of Liberty Project, please contact the Director at [email protected]. -

Understanding, Evaluating, and Extending Theories of Democratic Backsliding

Unwelcome Change: Understanding, Evaluating, and Extending Theories of Democratic Backsliding Ellen Lust Department of Political Science Yale University 115 Prospect Street Rosenkranz Hall New Haven, CT 06520 David Waldner Department of Politics University of Virginia 1540 Jefferson Park Avenue Gibson Hall Charlottesville, VA 22904 Final Version Submitted June 11, 2015 This publication was prepared under a Subaward funded by the Institute of International Education (IIE) under the Democracy Fellows and Grants (DFG) Program, award # AID-OAA-A-12-00039, funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views, analysis, or policies of IIE or USAID, nor does any mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by IIE or USAID. TABLE OF CONTENTS Democratic Backsliding ......................................................................................................................1 1. Conceptualizing Democratic Backsliding .............................................................................................. 2 2. Description and Evaluation of Theory Families ..................................................................................... 8 Part One: Structure, Agency, and Causation ........................................................................................8 Part Two: Introducing Six Theory Families ........................................................................................ 10 1. -

Polyarchies, Competitive Oligarchies, Or Inclusive Hegemonies? 23 Global Intergovernmental Organizations Compared

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Lopes, Dawisson Belém Working Paper Polyarchies, Competitive Oligarchies, or Inclusive Hegemonies? 23 Global Intergovernmental Organizations Compared GIGA Working Papers, No. 265 Provided in Cooperation with: GIGA German Institute of Global and Area Studies Suggested Citation: Lopes, Dawisson Belém (2015) : Polyarchies, Competitive Oligarchies, or Inclusive Hegemonies? 23 Global Intergovernmental Organizations Compared, GIGA Working Papers, No. 265, German Institute of Global and Area Studies (GIGA), Hamburg This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/107631 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu Inclusion of a paper in the Working Papers series does not constitute publication and should limit in any other venue. -

Working Paper 78

INSTITUTE Rethinking Consensus vs. Majoritarian Democracy Michael Coppedge October 2018 Working Paper SERIES 2018:78 THE VARIETIES OF DEMOCRACY INSTITUTE Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) is a new approach to conceptualization and measurement of democracy. The headquarters – the V-Dem Institute – is based at the University of Gothenburg with 17 staff. The project includes a worldwide team with six Principal Investigators, 14 Project Managers, 30 Regional Managers, 170 Country Coordinators, Research Assistants, and 3,000 Country Experts. The V-Dem project is one of the largest ever social science research-oriented data collection programs. Please address comments and/or queries for information to: V-Dem Institute Department of Political Science University of Gothenburg Sprängkullsgatan 19, PO Box 711 SE 40530 Gothenburg Sweden E-mail: [email protected] V-Dem Working Papers are available in electronic format at www.v-dem.net. Copyright © 2018 by authors. All rights reserved. Rethinking Consensus vs. Majoritarian Democracy* Michael Coppedge Professor University of Notre Dame * This research project was supported by Riksbankens Jubileumsfond, Grant M13-0559:1, PI: Staffan I. Lindberg, V- Dem Institute, University of Gothenburg, Sweden; by Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation to Wallenberg Academy Fellow Staffan I. Lindberg, Grant 2013.0166, V-Dem Institute, University of Gothenburg, Sweden; as well as by internal grants from the Vice-Chancellor’s office, the Dean of the College of Social Sciences, and the Department of Political Science at University of Gothenburg. We performed simulations and other computational tasks using resources provided by the Notre Dame Center for Research Computing (CRC) through the High Performance Computing section and the Swedish National Infrastructure for Computing (SNIC) at the National Supercomputer Centre in Sweden, SNIC 2017/1-407 and 2017/1-68.