In the Footsteps of Sylvia Plath by Karen V

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Burnley - Todmorden - Rochdale/Halifax Bus Times SERVICES: 517, 589, 592

From 1 September 2009 - Issue 2 LEAFLET 68 Burnley - Todmorden - Rochdale/Halifax bus times SERVICES: 517, 589, 592 517 Burnley - Hebden Bridge - Halifax 589 Burnley - Todmorden - Rochdale 592 Burnley - Todmorden - Hebden Bridge - Halifax For other services between Burnley and Todmorden see Leaflet 71 BURNLEY - HALIFAX 517 HALIFAX - BURNLEY 517 via Hebden Bridge & Blackshaw Head via Hebden Bridge & Blackshaw Head Saturday Saturday Operator Code FCL FCL Operator Code FCL FCL Service Number 517 517 Service Number 517 517 BURNLEY Bus Station . 1400 1705 HALIFAX Bus Station . 1230 ..... BLACKSHAW HEAD . 1430 1735 TUEL LANE Top . 1242 ..... HEPTONSTALL . 1437 1742 MYTHOLMROYD Burnley Road . 1258 ..... HEBDEN BRIDGE New Road . 1449 1754 HEBDEN BRIDGE Rail Station . ..... 1604 MYTHOLMROYD Burnley Road . 1454 1759 HEBDEN BRIDGE New Road . 1303 1606 TUEL LANE Top . 1502 1807 HEPTONSTALL . 1313 1616 HALIFAX Bus Station . 1520 1825 BLACKSHAW HEAD . 1320 1623 BURNLEY Bus Station . 1352 1655 FCL - First Calderline FCL - First Calderline Do you need further local bus and rail information? ¤ BURNLEY - TODMORDEN - ROCHDALE 589 BURNLEY - TODMORDEN - HALIFAX 592 via Hebden Bridge Monday to Friday Operator Code FCL FCL FCL FCL FCL FCL FCL FCL FCL FCL FCL FCL FCL FCL FCL FCL FCL Service Number 589 589 592 589 592 589 592 589 592 589 592 589 592 589 592 589 592 Notes A BURNLEY Bus Station . ..... 0625 0655 0725 0755 0825 0855 0925 0955 1025 55 25 1655 1725 1750 1825 1850 MERECLOUGH Fighting Cocks . ..... 0633 0703 0733 0803 0833 0903 0933 1003 1033 03 33 1703 1733 1758 1833 1858 PORTSMOUTH Burnley Road . 0540 0645 0715 0745 0815 0845 0915 0945 1015 1045 15 45 1715 1745 1810 1845 1910 TODMORDEN Bus Station arr . -

Biographical Task – Charlotte Brontë

CHARLOTTE1 BRONTË Biographical task - Charlotte Brontë At this stop you are going to learn about another famous Victorian author named Charlotte Brontë; along with her sisters Emily and Anne, Charlotte is one of the most important female writers of her time and her work is still widely read today. Again this first task will require you to use the PiXL Edge skills of organisation and resilience in order to achieve the task effectively. You can work in teams or independently to undertake your research; if working in a team one of you will need to take on the role of the leader in order to allocate the research topics. 1. Charlotte was born in 1816 followed by her lesser known brother Branwell in 1817, Emily in 1818 and Anne in 1820. What was the name of the town that they were all born in? A: Thornton, Haworth B: Bradford, Yorkshire C: Barnsley, Sheffield D: Cramlington, Newcastle 2. As children, Charlotte and her brother Branwell wrote stories set in a fantasy world. What was the name of that world? Narnia Angria Rodania Eldasia 3. Under what male pseudonym did Charlotte Brontë publish some of her work: Currer Bell Charles Brontë 2 Christian Brown Cole Boseley 4. Which was the first novel Charlotte wrote, although it wasn’t published until after her death? Jane Eyre Shirley Villette The Professor 5. In Jane Eyre, Jane's friend Helen dies from tuberculosis. Which of Charlotte's sisters is this based on? Maria Elizabeth Both 6. One of Charlotte's author friends described her as "underdeveloped, thin and more than half a head shorter than I .. -

45 Train Times Leeds to Hebden Bridge and Huddersfield

TT 45.qxp_Layout 1 01/11/2019 13:12 Page 2 Train times 45 15 December 2019 – 16 May 2020 Leeds to Hebden Bridge and Huddersfield Huddersfield to Castleford Parking available Staff in attendance Bicycle store facility Disabled assistance available Leeds Bramley Cottingley Morley New Pudsey Batley Bradford Interchange Dewsbury Ravensthorpe Normanton Low Moor Wakefield Castleford Halifax Mirfield Kirkgate Brighouse Sowerby Bridge Deighton Mytholmroyd Hebden Bridge Huddersfield Todmorden northernrailway.co.uk TT 45.qxp_Layout 1 01/11/2019 13:12 Page 3 This timetable shows all train services for Leeds to Hebden Bridge and HuddersfieldServices between. Other operators N run direct services between these stations. How to read this timetable Look down the left hand column for your departure s station. Read across until you find a suitable departure time. Read down the column to find the arrival time at your destination. Through services are shown in bold type (this means you won’t have to change trains). Connecting services are shown in light type. If you travel on a connecting service, change at the next station shown in bold or if you arrive on a connecting service,W change at the last station shown in bold, unless a ai footnote advises otherwise. Minimum connection times All stations have a minimum connection time of p 5 minutes unless stated. Leeds 10 minutes and Wakefield Westgate 7 minutes. F c Community Rail Partnerships and community groups d l We support a number of active community rail S t partnerships (CRPs) across our network. CRPs bring t d together local communities and the rail industry to d C deliverC benefits to both, and encourage use of the lines they represent. -

Heptonstall Newsletter Nov 2012 Colour

Age uk Age UK Calderdale & Kirklees Health and Commu- nity Services team are working with ‘Good Heptonstall Neighbour Scheme’. They aim to alleviate a lot of the problems associated with later life. Newsletter A project which the people of Heptonstall are likely Nov 2012 to hear a lot more about is ‘LOCAL LINK’. A newsletter covering Local Link is managed by Andrew Fearnley, who has events and issues for a network of Community Volunteers, mainly in rural areas of Calderdale, who act as ‘eyes and ears’ of everyone living within the their local communities, to support isolated older Civil Parish of Heptonstall people. Mary Cockcroft and Jean Leach are our vol- unteers in the Heptonstall area. Andrew also runs a scheme called ‘SAFE & WARM’, offering Home Energy Information and Advice, with support in applying for grants and reducing fuel poverty amongst vulnerable older people. The ‘ACTIVE BEFRIENDING PROJECT’, co- ordinated by Christine Henry offers ‘one to one’ sup- port for isolated people throughout Calderdale. Trained volunteers are linked with lonely older peo- ple who feel depressed and socially isolated. The scheme is focused on engaging people in activities with their befriender, in order to restore confidence and gain more out of life. People are referred to the scheme through various channels; usually by Health Professionals, but often by family or neighbours and sometimes by the per- son who actually needs the support. Andrew and Christine can be contacted at Age UKCK Choices Centre, Woolshops, Halifax. For fur- ther information Tel 01422 399830. Contents include Parish Council News Newsletters for the housebound Church News Do you know someone in the village who is housebound? Church Bells Refurbishment School Big Night Out If you do, please let us know and we’ll make sure that a copy of the Newsletter is delivered to them. -

Yorkshire Wildlife Park, Doncaster

Near by - Abbeydale Industrial Hamlet, Sheffield Aeroventure, Doncaster Brodsworth Hall and Gardens, Doncaster Cannon Hall Museum, Barnsley Conisbrough Castle and Visitors' Centre, Doncaster Cusworth Hall/Museum of South Yorkshire Life, Doncaster Elsecar Heritage Centre, Barnsley Eyam Hall, Eyam,Derbyshire Five Weirs Walk, Sheffield Forge Dam Park, Sheffield Kelham Island Museum, Sheffield Magna Science Adventure Centre, Rotherham Markham Grange Steam Museum, Doncaster Museum of Fire and Police, Sheffield Peveril Castle, Castleton, Derbyshire Sheffield and Tinsley Canal Trail, Sheffield Sheffield Bus Museum, Sheffield Sheffield Manor Lodge, Sheffield Shepherd's Wheel, Sheffield The Trolleybus Museum at Sandtoft, Doncaster Tropical Butterfly House, Wildlife and Falconry Centre, Nr Sheffeild Ultimate Tracks, Doncaster Wentworth Castle Gardens, Barnsley) Wentworth Woodhouse, Rotherham Worsbrough Mill Museum & Country Park, Barnsley Wortley Top Forge, Sheffield Yorkshire Wildlife Park, Doncaster West Yorkshire Abbey House Museum, Leeds Alhambra Theatre, Bradford Armley Mills, Leeds Bankfield Museum, Halifax Bingley Five Rise Locks, Bingley Bolling Hall, Bradford Bradford Industrial Museum, Bradford Bronte Parsonage Museum, Haworth Bronte Waterfall, Haworth Chellow Dean, Bradford Cineworld Cinemas, Bradford Cliffe Castle Museum, Keighley Colne Valley Museum, Huddersfield Colour Museum, Bradford Cookridge Hall Golf and Country Club, Leeds Diggerland, Castleford Emley Moor transmitting station, Huddersfield Eureka! The National Children's Museum, -

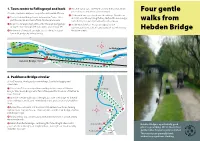

Four Gentle Walks from Hebden Bridge

1. Town centre to Fallingroyd and back ➍ Pass the signal box. Take the track near the railway, which passes houses and enters a beech wood. Four gentle 1½ miles, I hour at a slow pace; easy surface but muddy after rain. ➎ At the path end, cross back over the railway. Ahead is an ➊ Start at Hebden Bridge Tourist Information Centre. Walk old mill, once Walkey’s clog factory. Before the river bridge, past the cinema and turn left into Memorial Gardens. turn sharp left to join the hard-surfaced cycleway. walks from ➋ Cross the canal, and turn left to enter the park (using steps ➏ At the end of the cycleway, turn right past the or slope). Walk through the park, with canal on your left. stonemasons’ yard. Join the canal towpath to walk back to ➌ At the end of the park turn right to pass the train station. the town centre. Hebden Bridge Turn right under the railway bridge. Hebden Bridge ➊ ➋ Park to Mytholmroyd ➌ Burnley Road ➏ Canal Walkley’s ➍ River Calder Mill Hebden Bridge station ➎ 2. Packhorse Bridge circular 30 to 45 minutes, ¾ mile gentle road walking. Suitable for buggies and wheelchairs. Hebden Water ➊ Start at the 500 year old packhorse bridge in the centre of Hebden Foster Bridge Bridge. Walk down Bridge Gate. Turn left beyond the Shoulder of Mutton to ➍ cross the river. Keighley Road ➋ Take the riverside walkway to the right, just over the bridge. At the end of the walkway, turn left and immediately right , and continue along Valley Road. ➌ Follow the road round as it becomes Victoria Road. -

Wakefield, West Riding: the Economy of a Yorkshire Manor

WAKEFIELD, WEST RIDING: THE ECONOMY OF A YORKSHIRE MANOR By BRUCE A. PAVEY Bachelor of Arts Oklahoma State University Stillwater, Oklahoma 1991 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS May, 1993 OKLAHOMA STATE UNIVERSITY WAKEFIELD, WEST RIDING: THE ECONOMY OF A YORKSHIRE MANOR Thesis Approved: ~ ThesiSAd er £~ A J?t~ -Dean of the Graduate College ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am deeply indebted to to the faculty and staff of the Department of History, and especially the members of my advisory committee for the generous sharing of their time and knowledge during my stay at O.S.U. I must thank Dr. Alain Saint-Saens for his generous encouragement and advice concerning not only graduate work but the historian's profession in general; also Dr. Joseph Byrnes for so kindly serving on my committee at such short notice. To Dr. Ron Petrin I extend my heartfelt appreciation for his unflagging concern for my academic progress; our relationship has been especially rewarding on both an academic and personal level. In particular I would like to thank my friend and mentor, Dr. Paul Bischoff who has guided my explorations of the medieval world and its denizens. His dogged--and occasionally successful--efforts to develop my skills are directly responsible for whatever small progress I may have made as an historian. To my friends and fellow teaching assistants I extend warmest thanks for making the past two years so enjoyable. For the many hours of comradeship and mutual sympathy over the trials and tribulations of life as a teaching assistant I thank Wendy Gunderson, Sandy Unruh, Deidre Myers, Russ Overton, Peter Kraemer, and Kelly McDaniels. -

Scenic Bus Routes in West Y Rkshire

TICKETS Scenic Bus Routes For travel on buses only, ask the driver for a ‘MetroDay’ ticket. It costs £6 on the bus*. If you are in West Y rkshire travelling both on Saturday and Sunday, ask for a ‘Weekender’. It costs £8. They are valid on all buses at any time within West Yorkshire. *For travellers who need 3 or more day tickets on different days, you can save money by using an MCard smartcard - buy at Leeds Bus Station For travel on buses and trains, buy a ‘Train & Bus DayRover’ at Leeds Bus Station. It costs £8.20. If there are 2 of you, ask for a ‘Family DayRover’. This ticket includes up to 3 children. It costs £12.20. Mon - Fri these tickets are NOT valid on buses before 9.30 or trains before 9.30 and between 16.01 & 18.30 There is a Bus Map & Guide for different areas of West Yorkshire. The 4 maps that cover this tour are: Leeds, Wakefield, South Kirklees & Calderdale. They are available free at Leeds Bus Station. Every bus stop in the county has a timetable. Printed rail timetables for each line A Great Day Out are widely available. See page on left for online and social media Pennine Hills & Rishworth Moor sources of information Holme & Calder Valleys Wakefield & Huddersfield Please tell us what you think of this leaflet and how your trip went at [email protected] Have you tried Tour 1 to Haworth? All on the One Ticket! 110 to Kettlethorpe / Hall Green Every 10 minutes (20 mins on Leeds Rail Sundays). -

Calderdale Way Walking Route

Calderdale Way, walk route – dramatic West Yorkshire The Calderdale Way is a 50 mile (80 km) walk exploring the hills, moors and valleys of Calderdale. It is an ‘up and down’ journey with few level sections. The higher levels, however, provide some exceptionally fine panoramic views. There are some steep sections and there will be muddy parts following wet weather. Some areas of moorland are exposed. Mileage details, which are approximate, are given for longer sections with intermediate distances. The best walking and views as with all walks, would be in sunny weather following a dry spell. Appropriate footwear and clothing is needed for every part. The walk is accessible by public transport. Additionally it can be split into short walks also by using public transport. Additionally, there are many link paths. For example, an easy walk would be the three mile Norland to Ripponden section. Take the bus from Halifax to Norland and then walk on the level and downhill to Ripponden with another bus back to Halifax. Another even shorter walk combined with sight-seeing, would be to take the train to Hebden Bridge, bus to Heptonstall, and walk ¾ mile down to Hardcastle Crag and bus back to Hebden Bridge. The whole walk is circular and so can be started at any point; this starts at Brighouse. There are bus services to each of the distance points. Train services are available at Brighouse, Todmorden, Hebden Bridge, Mytholmroyd, Sowerby Bridge and Halifax. Route map and accommodation links at end of these details. Brighouse, Southowram, West Vale, Norland, Ripponden, Mill Bank (11.5 miles; start satnav HD6 1PQ) This section is a relatively easy introduction to the walk. -

Yorkshire Journal Issue 3 Autumn 2014

TThhee YYoorrkksshhiirree JJoouurrnnaall Issue 3 Autumn 2014 In this issue: One Summer Hornsea Mere Roman Signal Stations on the Yorkshire Coast The Curious Legend of Tom Bell and his Cave at Hardcastle Crags, Near Halifax Jervaulx Abbey This wooden chainsaw sculpture of a monk is by Andris Bergs. It was comissioned by the owners of Jervaulx Abbey to welcome visitors to the Abbey. Jervaulx was a Cistercian Abbey and the medieval monks wore habits, generally in a greyish-white, and sometimes brown and were referred to as the “White Monks” The sculptured monk is wearing a habit with the hood covering the head with a scapula. A scapula was a garment consisting of a long wide piece of woollen cloth worn over the shoulders with an opening for the head Some monks would also wear a cross on a chain around their necks Photo by Brian Wade The Yorkshire Journal Issue 3 Autumn 2014 Left: Kirkstall Abbey, Leeds in autumn, Photo by Brian Wade Cover: Hornsea Mere, Photo by Alison Hartley Editorial elcome to the autumn issue of The Yorkshire Journal. Before we W highlight the articles in this issue we would like to inform our readers that all our copies of Yorkshire Journal published by Smith Settle from 1993 to 2003 and then by Dalesman, up to winter issue 2004, have all been passed on to The Saltaire Bookshop, 1 Myrtle Place, Shipley, West Yorkshire BD18 4NB where they can be purchased. We no longer hold copies of these Journals. David Reynolds starts us off with the Yorkshire Television drama series ‘One Summer’ by Willy Russell. -

Review of the Spoken Word: Sylvia Plath (British Library 2010), ISBN

Plath Profiles 361 Review of The Spoken Word: Sylvia Plath (British Library 2010), ISBN: 978-0-712351-02-7 and The Spoken Word: Ted Hughes: Poems and Short Stories (British Library and BBC 2008), ISBN: 978-0-712305-49-5 Carol Bere Dramatic, visceral, occasionally mesmerizing, memorable—there is little question that these separate recordings from the archives of the BBC and the British Library of live and studio broadcasts of Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes reading their poetry offer sheer pleasure in themselves. Yet let me offer a brief caveat at the outset: this review is in no way meant to be a comparison of the poetry of Plath and Hughes, or a critical analysis of the ways in which they influenced each other's work—although I do assume mutual influence at various stages in their writing (and lives)—but rather a commentary on the separate BBC recordings, and perhaps a recognition of areas or periods of intersection in their careers. Hughes obviously had a much longer career, and these BBC recordings (two discs) reflect a span of over 30 years of writing, while the Plath recording (one disc) includes poems and interviews beginning in late l960 through January 1963. Along with knowledgeable introductions to the recordings by Peter K. Steinberg (Plath) and Alice Oswald (Hughes), respectively, these recordings are also invaluable guides to the early work (particularly in Plath's case), "hearing" both poets in the process of becoming, and, perhaps, gaining additional perspective on the poetry of both poets. What is also apparent in these recordings of Plath and Hughes is the necessity, or more realistically, the benefits of hearing poetry read aloud to fully understand the range of a poet's enterprise and achievement. -

Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes: Layers of Literary Collaboration and The

Plath Profiles 275 Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes: Layers of Literary Collaboration and the Perpetuation of the Poetic Voice Natalie Chambers The partnership of Ted Hughes and Sylvia Plath was arguably one of the most mutually productive literary pairings of the twentieth century, and while the work produced during their six-and-a-half year marriage was substantial in its sheer volume and artistic merit, the bulk of the critical discussion regarding their partnership focuses not on their prolific literary production but on the marriage itself and the events that led up to Plath's suicide in February of 1963. While countless books and critical essays have been written, at a distance, about this relationship—their partnership and the tumultuous passion that fueled their creative fires—these texts are inextricably rooted in speculation, cultivated by critical hypotheses and, ultimately, dependent upon the interpretations of outsiders. Even the most in-depth investigations of their marriage and respective works—like the many biographies and essays written by major Plath scholars Susan Van Dyne, Jacqueline Rose, Lynda Bundtzen, and Anne Stevenson, as well as the biography of their marriage written by Diane Middlebrook—still remain mere versions of the truth, individual interpretations of the details that constituted a collaborative life, the work it created, and the eventual culmination in Plath's death. It is not uncommon for artists to gain posthumous notoriety and critical attention, and thus sell more of their work, as was the case with Sylvia Plath. Though her death was undoubtedly a tragic loss of talent and silencing of a powerful poetic voice, it also evoked a conflagration of public and critical interest in her work and created a flurry of activity among the literary community to publish it.