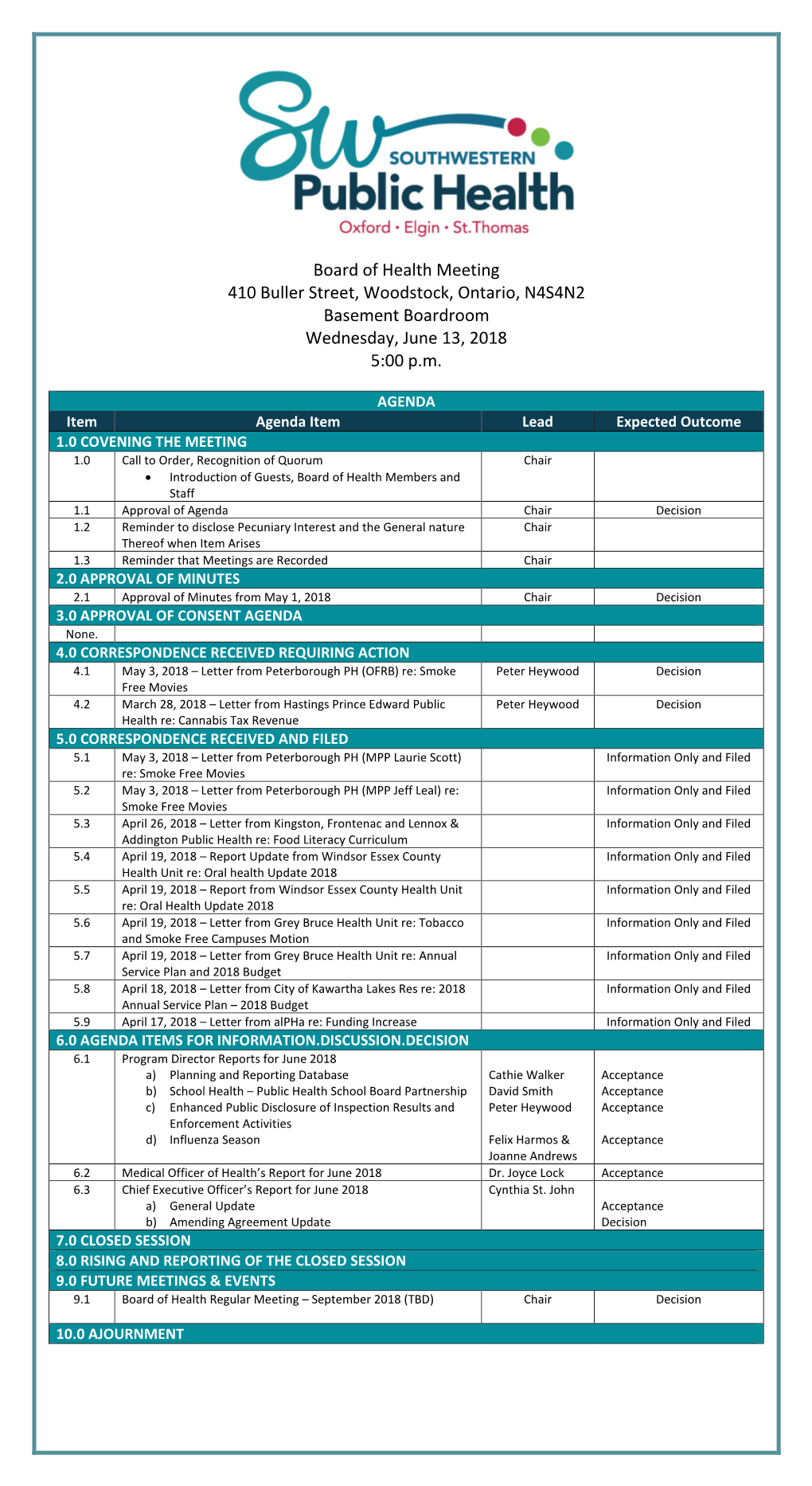

Meeting Package

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2018 Election New Democratic Party of Ontario Candidates

2018 Election New Democratic Party of Ontario Candidates NAME RIDING CONTACT INFORMATION Monique Hughes Ajax [email protected] Michael Mantha Algoma-Manitoulin [email protected] Pekka Reinio Barrie-Innisfil [email protected] Dan Janssen Barrie-Springwater-Ono- [email protected] Medonte Joanne Belanger Bay of Quinte [email protected] Rima Berns-McGown Beaches-East York [email protected] Sara Singh Brampton Centre [email protected] Gurratan Singh Brampton East [email protected] Jagroop Singh Brampton West [email protected] Alex Felsky Brantford-Brant [email protected] Karen Gventer Bruce-Grey-Owen Sound [email protected] Andrew Drummond Burlington [email protected] Marjorie Knight Cambridge [email protected] Jordan McGrail Chatham-Kent-Leamington [email protected] Marit Stiles Davenport [email protected] Khalid Ahmed Don Valley East [email protected] Akil Sadikali Don Valley North [email protected] Joel Usher Durham [email protected] Robyn Vilde Eglinton-Lawrence [email protected] Amanda Stratton Elgin-Middlesex-London [email protected] NAME RIDING CONTACT INFORMATION Taras Natyshak Essex [email protected] Mahamud Amin Etobicoke North [email protected] Phil Trotter Etobicoke-Lakeshore [email protected] Agnieszka Mylnarz Guelph [email protected] Zac Miller Haliburton-Kawartha lakes- [email protected] -

District Name

District name Name Party name Email Phone Algoma-Manitoulin Michael Mantha New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-1938 Bramalea-Gore-Malton Jagmeet Singh New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-1784 Essex Taras Natyshak New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-0714 Hamilton Centre Andrea Horwath New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-7116 Hamilton East-Stoney Creek Paul Miller New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-0707 Hamilton Mountain Monique Taylor New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-1796 Kenora-Rainy River Sarah Campbell New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-2750 Kitchener-Waterloo Catherine Fife New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-6913 London West Peggy Sattler New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-6908 London-Fanshawe Teresa J. Armstrong New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-1872 Niagara Falls Wayne Gates New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 212-6102 Nickel Belt France GŽlinas New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-9203 Oshawa Jennifer K. French New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-0117 Parkdale-High Park Cheri DiNovo New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-0244 Timiskaming-Cochrane John Vanthof New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-2000 Timmins-James Bay Gilles Bisson -

Government of Ontario Key Contact Ss

GOVERNMENT OF ONTARIO 595 Bay Street Suite 1202 Toronto ON M5G 2C2 KEY CONTACTS 416 586 1474 enterprisecanada.com PARLIAMENTARY MINISTRY MINISTER DEPUTY MINISTER PC CRITICS NDP CRITICS ASSISTANTS Steve Orsini Patrick Brown (Cabinet Secretary) Steve Clark Kathleen Wynne Andrea Horwath Steven Davidson (Deputy Leader + Ethics REMIER S FFICE Deb Matthews Ted McMeekin Jagmeet Singh P ’ O (Policy & Delivery) and Accountability (Deputy Premier) (Deputy Leader) Lynn Betzner Sylvia Jones (Communications) (Deputy Leader) Lorne Coe (Post‐Secondary ADVANCED EDUCATION AND Han Dong Peggy Sattler Education) Deb Matthews Sheldon Levy Yvan Baker Taras Natyshak SKILLS DEVELOPMENT Sam Oosterhoff (Digital Government) (Digital Government) +DIGITAL GOVERNMENT (Digital Government) AGRICULTURE, FOOD AND RURAL AFFAIRS Jeff Leal Deb Stark Grant Crack Toby Barrett John Vanthof +SMALL BUSINESS ATTORNEY GENERAL Yasir Naqvi Patrick Monahan Lorenzo Berardinetti Randy Hillier Jagmeet Singh Monique Taylor Gila Martow (Children, Jagmeet Singh HILDREN AND OUTH ERVICES Youth and Families) C Y S Michael Coteau Alex Bezzina Sophie Kiwala (Anti‐Racism) Lisa MacLeod +ANTI‐RACISM Jennifer French (Anti‐Racism) (Youth Engagement) Jennifer French CITIZENSHIP AND IMMIGRATION Laura Albanese Shirley Phillips (Acting) Shafiq Qaadri Raymond Cho Cheri DiNovo (LGBTQ Issues) Lisa Gretzky OMMUNITY AND OCIAL ERVICES Helena Jaczek Janet Menard Ann Hoggarth Randy Pettapiece C S S (+ Homelessness) Matt Torigian Laurie Scott (Community Safety) (Community Safety) COMMUNITY SAFETY AND Margaret -

Ontario Government Quick Reference Guide: Key Officials and Opposition Critics August 2014

Ontario Government Quick Reference Guide: Key Officials and Opposition Critics August 2014 Ministry Minister Chief of Staff Parliamentary Assistant Deputy Minister PC Critic NDP Critic Hon. David Aboriginal Affairs Milton Chan Vic Dhillon David de Launay Norm Miller Sarah Campbell Zimmer Agriculture, Food & Rural Affairs Hon. Jeff Leal Chad Walsh Arthur Potts Deb Stark Toby Barrett N/A Hon. Lorenzo Berardinetti; Sylvia Jones (AG); Jagmeet Singh (AG); Attorney General / Minister responsible Shane Madeleine Marie-France Lalonde Patrick Monahan Gila Martow France Gélinas for Francophone Affairs Gonzalves Meilleur (Francophone Affairs) (Francophone Affairs) (Francophone Affairs) Granville Anderson; Alexander Bezzina (CYS); Jim McDonell (CYS); Monique Taylor (CYS); Children & Youth Services / Minister Hon. Tracy Omar Reza Harinder Malhi Chisanga Puta-Chekwe Laurie Scott (Women’s Sarah Campbell responsible for Women’s Issues MacCharles (Women’s Issues) (Women’s Issues) Issues) (Women’s Issues) Monte Kwinter; Cristina Citizenship, Immigration & International Hon. Michael Christine Innes Martins (Citizenship & Chisanga Puta-Chekwe Monte McNaughton Teresa Armstrong Trade Chan Immigration) Cindy Forster (MCSS) Hon. Helena Community & Social Services Kristen Munro Soo Wong Marguerite Rappolt Bill Walker Cheri DiNovo (LGBTQ Jaczek Issues) Matthew Torigian (Community Community Safety & Correctional Hon. Yasir Brian Teefy Safety); Rich Nicholls (CSCS); Bas Balkissoon Lisa Gretzky Services / Government House Leader Naqvi (GHLO – TBD) Stephen Rhodes (Correctional Steve Clark (GHLO) Services) Hon. David Michael Government & Consumer Services Chris Ballard Wendy Tilford Randy Pettapiece Jagmeet Singh Orazietti Simpson Marie-France Lalonde Wayne Gates; Economic Development, Employment & Hon. Brad (Economic Melanie Wright Giles Gherson Ted Arnott Percy Hatfield Infrastructure Duguid Development); Peter (Infrastructure) Milczyn (Infrastructure) Hon. Liz Education Howie Bender Grant Crack George Zegarac Garfield Dunlop Peter Tabuns Sandals Hon. -

Angry Birds: Twitter Harassment of Canadian Female Politicians By

Angry Birds: Twitter Harassment of Canadian Female Politicians By Jess Ann Gordon Submitted to the Faculty of Extension University of Alberta In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Communications and Technology August 5, 2019 2 Acknowledgments Written with gratitude on the unceded traditional territories of the Skwxw�7mesh (Squamish), Səl̓ �lwətaʔ/Selilwitulh (Tsleil-Waututh), and xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam) Nations, and on Treaty 6 territory, the traditional lands of diverse Indigenous peoples including the Cree, Blackfoot, Métis, Nakota Sioux, Iroquois, Dene, Ojibway, Saulteaux, Anishinaabe, Inuit, and many others. I would like to take this opportunity to thank my friends, family, cohort colleagues, and professors who contributed to this project. Thank you to my project supervisor, Dr. Gordon Gow, for his steadying support throughout the project and the many valuable suggestions. Thank you as well to Dr. Stanley Varnhagen, who provided invaluable advice on the design and content of the survey. I am grateful to both Dr. Gow and Dr. Varnhagen for sharing their expertise and guidance to help bring this project to life. Thank you to my guinea pigs, who helped me to identify opportunities and errors in the draft version of the survey: Natalie Crawford Cox, Lana Cuthbertson, Kenzie Gordon, Ross Gordon, Amanda Henry, Lucie Martineau, Kory Mathewson, and Ian Moore. Thank you to my MACT 2017 cohort colleagues and professors their support and encouragement. Particularly, I’d like to thank Ryan O’Byrne for helping me to clarify the project concept in its infant stages, and for being a steadfast cheerleader and friend throughout this project and the entire MACT program. -

Student Alliance

ONTARIO UNDERGRADUATE STUDENT ALLIANCE ADVOCACY CONFERENCE 2020 November 16-19th ABOUT OUSA The Ontario Undergraduate Student Alliance (OUSA) represents the interests of approximately 150,000 professional and undergraduate, full-time and part-time university students at eight student associations across Ontario. Our vision is for an accessible, affordable, accountable and high quality post-secondary education in Ontario. OUSA’s approach to advocacy is based on creating substantive, student driven, and evidence-based policy recommendations. INTRODUCTION Student leaders representing over 150,000 undergraduate students from across Ontario attended OUSA’s annual Student Advocacy Conference from November 16th to the 19th. Delegates met with over 50 MPPs from four political parties and sector stakeholders to discuss the future of post-secondary education in Ontario and advance OUSA’s advocacy priorities. Over five days, the student leaders discussed student financial aid, quality of education, racial equity, and student mental health. As we navigate the global pandemic, OUSA recommends improvements to the Ontario Student Assistance Program (OSAP), guidance and support for quality online learning, training and research to support racial equity, and funding for student mental health services. Overall, OUSA received a tremendous amount of support from members and stakeholders. ATTENDEES Julia Periera (WLUSU) Eric Chappell (SGA-AGÉ) Devyn Kelly (WLUSU) Nathan Barnett (TDSA) Mackenzy Metcalfe (USC) Rayna Porter (TDSA) Matt Reesor (USC) Ryan Tse (MSU) Megan Town (WUSA) Giancarlo Da-Ré (MSU) Abbie Simpson (WUSA) Tim Gulliver (UOSU-SÉUO) Hope Tuff-Berg (BUSU) Chris Yendt (BUSU) Matthew Mellon (AMS) Alexia Henriques (AMS) Malek Abou-Rabia (SGA-AGÉ) OUSA MET WITH A VARIETY OF STAKEHOLDERS MPPS CABINET MINISTERS Minister Michael Tibollo MPP Stephen Blais Office of Minister Monte McNaughton MPP Jeff Burch Office of Minister Peter Bethlenfalvy MPP Teresa Armstrong . -

Middlesex-London Board of Health

AGENDA MIDDLESEX-LONDON BOARD OF HEALTH Thursday, July 19, 2018, 7:00 p.m. 399 RIDOUT STREET NORTH SIDE ENTRANCE, (RECESSED DOOR) Board of Health Boardroom MISSION - MIDDLESEX-LONDON HEALTH UNIT The mission of the Middlesex-London Health Unit is to promote and protect the health of our community. MEMBERS OF THE BOARD OF HEALTH Ms. Joanne Vanderheyden (Chair) Ms. Trish Fulton (Vice Chair) Ms. Maureen Cassidy M r. Michael Clarke Mr. Jesse Helmer Mr. Trevor Hunter Ms. Tino Kasi Mr. Marcel Meyer Mr. Ian Peer Mr. Kurtis Smith SECRETARY -TREASURER Dr. Christopher Mackie DISCLOSURE OF CONFLICTS OF INTEREST APPROVAL OF AGENDA APPROVAL OF MINUTES June 21, 2018 – Board of Health meeting Receive: July 5, 2018 - Finance & Facilities Committee meeting DELEGATIONS 7:05 – 7:15 p.m. Dr. Ken Lee, Addictions Services Thames Valley re: Item #2 Nurse Practitioner Secondment Follow-up (Report No. 045-18) 7:15 – 7:25 p.m. Dr. Fatih Sekercioglu, Manager Safe Water, Rabies and Vector Borne Disease, Environmental Health & Infectious Diseases Division re: Item #3 Small Non- Community Drinking Water Systems (Report No. 046-18) 7:25 – 7:35 p.m. Ms. Joanne Vanderheyden, Finance & Facilities Committee Meeting Update, re: Item #1 July 5, 2018 Finance & Facilities Committee Meeting (Report No. 044-18) 1 Item # Item Delegation Recommendation Information Link to Additional Brief Overview Report Name and Number Information Delegations & Committee Reports Finance & Facilities July 5, 2018 To receive information and consider Committee Meeting Agenda recommendations from the July 5, 1 July 5, 2018 x x x 2018 Finance & Facilities Committee Minutes meeting. (Report No. -

Escribe Agenda Package

Council Agenda Including Addeds 2018-2022 City Council Inaugural Meeting December 3, 2018, 6:00 PM London Convention Centre 300 York Street, London The City of London is committed to making every effort to provide alternate formats and communication supports for Council, Standing or Advisory Committee meetings and information, upon request. To make a request for any City service, please contact [email protected] or 519-661-2489 ext. 2425. The Council will break for dinner at approximately 6:30 PM, as required. Pages 1. Processional Sgt.-at-Arms Lauren Eastman London Police Service Colour Guard Karen Widmeyer, Piper 2. National Anthem 3. Greetings from the Federal Members of Parliament 4. Greetings from Members of Provincial Parliament 5. Appreciation to Government and Community Representatives 6. Declarations of Office Administered to Mayor-Elect Ed Holder by Cathy Saunders, City Clerk Administered to the Councillors-Elect by Cathy Saunders, City Clerk 7. Investiture of the Mayor's Chain of Office Glen Pearson, Community Activist and former Member of Parliament 8. Raising of the Mace Sgt.-at-Arms Lauren Eastman 9. The Mayor's Inaugural Address His Worship Mayor Ed Holder 10. Disclosures of Pecuniary Interest 11. Appointment of Deputy Mayor 12. Communications 3 (ADDED) Greetings from Terence Kernaghan, MPP (London North Centre) (ADDED) Greetings from Karen Vecchio, MP (Elgin-Middlesex-London) (ADDED) Greetings from Teresa Armstrong, MPP (London-Fanshawe) ADDED) Congratulations Letter from the Honourable Steve Clark, Minister of Municipal Affairs and Housing (ADDED) Greetings from Peggy Sattler, MPP (London West) (ADDED) Greetings from Kate Young, M.P. (London West) 13. By-laws By-laws to be read a first, second and third time: 13.1 Bill No. -

Government of Ontario Key Contact Ss

GOVERNMENT OF ONTARIO 595 Bay Street Suite 1202 Toronto ON M5G 2C2 KEY CONTACTS 416 586 1474 enterprisecanada.com PARLIAMENTARY MINISTRY MINISTER DEPUTY MINISTER PC CRITICS NDP CRITICS ASSISTANTS Steve Orsini Patrick Brown (Cabinet Secretary) Kathleen Wynne Steve Clark Steven Davidson REMIER S FFICE Deb Matthews Ted McMeekin (Deputy Leader) Andrea Horwath P ’ O (Policy & Delivery) (Deputy Premier) Sylvia Jones Lynn Betzner (Deputy Leader) (Communications) Lorne Coe (Post-Secondary ADVANCED EDUCATION AND Han Dong Peggy Sattler Education) Deb Matthews Greg Orencsak Yvan Baker Taras Natyshak SKILLS DEVELOPMENT Sam Oosterhoff (Digital Government) (Digital Government) + DIGITAL GOVERNMENT (Digital Government) AGRICULTURE, FOOD AND RURAL AFFAIRS Jeff Leal Greg Meredith Grant Crack Toby Barrett John Vanthof + SMALL BUSINESS ATTORNEY GENERAL Yasir Naqvi Paul Boniferro Lorenzo Berardinetti Randy Hillier Gilles Bisson Monique Taylor Gila Martow (Children, Teresa Armstrong HILDREN AND OUTH ERVICES Youth and Families) C Y S Michael Coteau Nancy Matthews Sophie Kiwala (Anti-Racism) Lisa MacLeod +ANTI-RACISM Jennifer French (Anti-Racism) (Youth Engagement) CITIZENSHIP AND IMMIGRATION Laura Albanese Alex Bezzina Shafiq Qaadri Raymond Cho Jennifer French Lisa Gretzky OMMUNITY AND OCIAL ERVICES Helena Jaczek Janet Menard Ann Hoggarth Randy Pettapiece C S S (+ Homelessness) Matt Torigian Laurie Scott COMMUNITY SAFETY AND (Community Safety) (Community Safety) Marie-France Lalonde Soo Wong Taras Natyshak CORRECTIONAL SERVICES Sam Erry Rick Nicholls (Correctional -

Conscience Campaign Notes Notes to Pastor: 1. Please Distribute the Letter from Bishop Fabbro to the Faithful 2. Learn More Abou

Conscience Campaign Notes Notes to Pastor: 1. Please distribute the letter from Bishop Fabbro to the faithful 2. Learn more about Bill C-7, MAiD and Conscience Rights (see below) 3. Please include a prayer of the faithful. • That the vulnerable will find hope through the healing power of Christ’s love and from caring companions, we pray to the Lord. Lord hear our prayer That vulnerable patients will be able to live out their lives in an environment of dignity and respect, we pray to the Lord. Lord, hear our prayer • That Ontario will be a province in which the conscience rights of doctors, nurses and other health care providers are respected and valued, we pray to the Lord. Lord, hear our prayer • That filled with the strength of Christ’s love, and supported by friends and caregivers, the vulnerable will choose life rather than death, we pray to the Lord. Lord hear our prayer • That people with disabilities will understand their value and contribution to the church and society, we pray to the Lord. Lord hear our prayer For your convenience, please find the link below to the Google Drive which contains French and English campaign documents (If you are having difficulty opening this link, it may help to cut and paste this link) bit.ly/2021ConscienceCampaign Notes for all the faithful 1. Read the letter from Bishop Fabbro 2. Learn more about MAiD (assisted suicide) and Conscience Rights and to come see issues in the light of our faith 3. If you would like to view a video with testimonies from healthcare providers, please click here: bit.ly/2021ConscienceVideo 4. -

At a Time When Ontario's Universities Already Receive The

Sent by e-mail February 25, 2019 Dear Honorable Merrilee Fullerton: At a time when Ontario’s universities already receive the lowest per-student funding in Canada, the University of Western Ontario Faculty Association (UWOFA) urges your government not to cut operating grants to universities in the upcoming provincial budget. A decrease in funding to post-secondary institutions will have a negative impact on the quality of education needed to make Ontario competitive. Budget cuts will most certainly affect university faculty members with precarious employment, many of whom work on short-term contracts that may not be renewed when universities face budget cuts. Contract faculty are among Ontario’s best university teachers. They are a vital part of the high-quality education that our students deserve. Any further reduction in operating grants will leave our contract faculty colleagues, our universities, our communities, and indeed our province, further behind. Universities are already being forced to absorb revenue losses as a result of the 10% tuition reduction in the 2019-2020 school year. That makes it even more critical that core operating grants be maintained for all Ontario post-secondary institutions. At Western, departments and faculties are being asked to model cuts in anticipation of budget strife due to provincial policy changes which will no doubt impact the quality of education Ontario students deserve. We ask you not to cut operating grants and instead provide robust public funding for Ontario universities, which will only strengthen the quality of post-secondary education in our province. Can you commit to our request? We look forward to your response. -

2018 Ontario Candidates List May 8.Xlsx

Riding Ajax Joe Dickson ‐ @MPPJoeDickson Rod Phillips ‐ @RodPhillips01 Algoma ‐ Manitoulin Jib Turner ‐ @JibTurnerPC Michael Mantha ‐ @ M_Mantha Aurora ‐ Oak Ridges ‐ Richmond Hill Naheed Yaqubian ‐ @yaqubian Michael Parsa ‐ @MichaelParsa Barrie‐Innisfil Ann Hoggarth ‐ @AnnHoggarthMPP Andrea Khanjin ‐ @Andrea_Khanjin Pekka Reinio ‐ @BI_NDP Barrie ‐ Springwater ‐ Oro‐Medonte Jeff Kerk ‐ @jeffkerk Doug Downey ‐ @douglasdowney Bay of Quinte Robert Quaiff ‐ @RQuaiff Todd Smith ‐ @ToddSmithPC Joanne Belanger ‐ No social media. Beaches ‐ East York Arthur Potts ‐ @apottsBEY Sarah Mallo ‐ @sarah_mallo Rima Berns‐McGown ‐ @beyrima Brampton Centre Harjit Jaswal ‐ @harjitjaswal Sara Singh ‐ @SaraSinghNDP Brampton East Parminder Singh ‐ @parmindersingh Simmer Sandhu ‐ @simmer_sandhu Gurratan Singh ‐ @GurratanSingh Brampton North Harinder Malhi ‐ @Harindermalhi Brampton South Sukhwant Thethi ‐ @SukhwantThethi Prabmeet Sarkaria ‐ @PrabSarkaria Brampton West Vic Dhillon ‐ @VoteVicDhillon Amarjot Singh Sandhu ‐ @sandhuamarjot1 Brantford ‐ Brant Ruby Toor ‐ @RubyToor Will Bouma ‐ @WillBoumaBrant Alex Felsky ‐ @alexfelsky Bruce ‐ Grey ‐ Owen Sound Francesca Dobbyn ‐ @Francesca__ah_ Bill Walker ‐ @billwalkermpp Karen Gventer ‐ @KarenGventerNDP Burlington Eleanor McMahon ‐@EMcMahonBurl Jane McKenna ‐ @janemckennapc Cambridge Kathryn McGarry ‐ Kathryn_McGarry Belinda Karahalios ‐ @MrsBelindaK Marjorie Knight ‐ @KnightmjaKnight Carleton Theresa Qadri ‐ @TheresaQadri Goldie Ghamari ‐ @gghamari Chatham‐Kent ‐ Leamington Rick Nicholls ‐ @RickNichollsCKL Jordan