Diet Variation of the South American Snake-Necked Turtle (Hydromedusa Tectifera)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geographic Variation in the Matamata Turtle, Chelus Fimbriatus, with Observations on Its Shell Morphology and Morphometry

n*entilkilt ilil Biok,gr', 1995. l(-l):19: 1995 by CheloninD Research Foundltion Geographic Variation in the Matamata Turtle, Chelus fimbriatus, with Observations on its Shell Morphology and Morphometry MlncBLo R. SANcnnz-Vu,urcnAr, PnrER C.H. PnrrcHARD:, ArrnEro P.rorrLLo-r, aNn Onan J. LINlnBs3 tDepartment of Biological Anthropolog-,- and Anatomy, Duke lJniversin' Medical Cetter. Box 3170, Dtu'hcun, North Carolina277l0 USA IFat 919-684-8034]; 2Florida Audubotr Societ-t, 460 High,n;a,- 436, Suite 200, Casselberry, Florida 32707 USA: iDepartanento de Esttdios Anbientales, llniyersitlad Sinzrin Bolltnt", Caracas ]O80-A, APDO 89OOO l/enerte\a Ansrucr. - A sample of 126 specimens of Chelusftmbriatus was examined for geographic variation and morphology of the shell. A high degree of variation was found in the plastral formula and in the shape and size of the intergular scute. This study suggests that the Amazon population of matamatas is different from the Orinoco population in the following characters: shape ofthe carapace, plastral pigmentation, and coloration on the underside of the neck. Additionatly, a preliminary analysis indicates that the two populations could be separated on the basis of the allometric growth of the carapace in relation to the plastron. Kry Wonus. - Reptilia; Testudinesl Chelidae; Chelus fimbriatus; turtle; geographic variationl allometryl sexual dimorphism; morphology; morphometryl osteology; South America 'Ihe matamata turtle (Chelus fimbricttus) inhabits the scute morpholo..ey. Measured characters (in all cases straight- Amazon, Oyapoque. Essequibo. and Orinoco river systems line) were: maximum carapace len.-uth (CL). cArapace width of northern South America (Iverson. 1986). Despite a mod- at the ler,'el of the sixth marginal scute (CW). -

Contents Fritz U., Y

CONTENTS Fritz U., Y. V. Kornilev, M. Vamberger, N. Natchev & P. Havaš – The Fifth International Symposium on Emys orbicularis and the other European Freshwater Turtles, Kiten, Bulgaria: Over Twenty Years of Scientific Collaboration ...............................................................................................................................................3–7 Saçdanaku E. & I. Haxhiu – Distribution, Habitats and Preliminary Data on the Population Structure of the European Pond Turtle, Emys orbicularis (Linnaeus, 1758), in Vlora Bay, Albania ........................................9–14 Dux M., D. Doktór, A. Hryniewicz & B. Prusak – Evaluation of 11 Microsatellite Loci for Reconstructing of Kinship Groups in the European Pond Turtle, Emys orbicularis (Linnaeus, 1758) ............................................15–22 Ayaz D., K. Çiçek, Y. Bayrakci & C. V. Tok – Reproductive Ecology of the European Pond Turtle, Emys orbicularis (Linnaeus, 1758), from Mediterranean Turkey .............................................................................23–29 Bayrakci Y., D. Ayaz, K. Çiçek & S. İlhan – Population Dynamics of the European Pond Turtle, Emys orbicularis (L., 1758) (Testudinata: Emydidae) from Lake Eğirdir (Isparta, Turkey) ...................................31–35 Bîrsan C. C., R. Iosif, P. Székely & D. Cogălniceanu – Spatio-temporal Bias in the Perceived Distribution of the European Pond Turtle, Emys orbicularis (Linnaeus, 1758), in Romania .......................................................37–41 Bona M., S. Danko, -

Buhlmann Etal 2009.Pdf

Chelonian Conservation and Biology, 2009, 8(2): 116–149 g 2009 Chelonian Research Foundation A Global Analysis of Tortoise and Freshwater Turtle Distributions with Identification of Priority Conservation Areas 1 2 3 KURT A. BUHLMANN ,THOMAS S.B. AKRE ,JOHN B. IVERSON , 1,4 5 6 DENO KARAPATAKIS ,RUSSELL A. MITTERMEIER ,ARTHUR GEORGES , 7 5 1 ANDERS G.J. RHODIN ,PETER PAUL VAN DIJK , AND J. WHITFIELD GIBBONS 1University of Georgia, Savannah River Ecology Laboratory, Drawer E, Aiken, South Carolina 29802 USA [[email protected]; [email protected]]; 2Department of Biological and Environmental Sciences, Longwood University, 201 High Street, Farmville, Virginia 23909 USA [[email protected]]; 3Department of Biology, Earlham College, Richmond, Indiana 47374 USA [[email protected]]; 4Savannah River National Laboratory, Savannah River Site, Building 773-42A, Aiken, South Carolina 29802 USA [[email protected]]; 5Conservation International, 2011 Crystal Drive, Suite 500, Arlington, Virginia 22202 USA [[email protected]; [email protected]]; 6Institute for Applied Ecology Research Group, University of Canberra, Australian Capitol Territory 2601, Canberra, Australia [[email protected]]; 7Chelonian Research Foundation, 168 Goodrich Street, Lunenburg, Massachusetts 01462 USA [[email protected]] ABSTRACT. – There are currently ca. 317 recognized species of turtles and tortoises in the world. Of those that have been assessed on the IUCN Red List, 63% are considered threatened, and 10% are critically endangered, with ca. 42% of all known turtle species threatened. Without directed strategic conservation planning, a significant portion of turtle diversity could be lost over the next century. Toward that conservation effort, we compiled museum and literature occurrence records for all of the world’s tortoises and freshwater turtle species to determine their distributions and identify priority regions for conservation. -

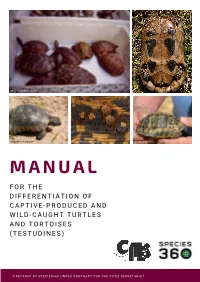

Manual for the Differentiation of Captive-Produced and Wild-Caught Turtles and Tortoises (Testudines)

Image: Peter Paul van Dijk Image:Henrik Bringsøe Image: Henrik Bringsøe Image: Andrei Daniel Mihalca Image: Beate Pfau MANUAL F O R T H E DIFFERENTIATION OF CAPTIVE-PRODUCED AND WILD-CAUGHT TURTLES AND TORTOISES (TESTUDINES) PREPARED BY SPECIES360 UNDER CONTRACT FOR THE CITES SECRETARIAT Manual for the differentiation of captive-produced and wild-caught turtles and tortoises (Testudines) This document was prepared by Species360 under contract for the CITES Secretariat. Principal Investigators: Prof. Dalia A. Conde, Ph.D. and Johanna Staerk, Ph.D., Species360 Conservation Science Alliance, https://www.species360.orG Authors: Johanna Staerk1,2, A. Rita da Silva1,2, Lionel Jouvet 1,2, Peter Paul van Dijk3,4,5, Beate Pfau5, Ioanna Alexiadou1,2 and Dalia A. Conde 1,2 Affiliations: 1 Species360 Conservation Science Alliance, www.species360.orG,2 Center on Population Dynamics (CPop), Department of Biology, University of Southern Denmark, Denmark, 3 The Turtle Conservancy, www.turtleconservancy.orG , 4 Global Wildlife Conservation, globalwildlife.orG , 5 IUCN SSC Tortoise & Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group, www.iucn-tftsG.org. 6 Deutsche Gesellschaft für HerpetoloGie und Terrarienkunde (DGHT) Images (title page): First row, left: Mixed species shipment (imaGe taken by Peter Paul van Dijk) First row, riGht: Wild Testudo marginata from Greece with damaGe of the plastron (imaGe taken by Henrik BrinGsøe) Second row, left: Wild Testudo marginata from Greece with minor damaGe of the carapace (imaGe taken by Henrik BrinGsøe) Second row, middle: Ticks on tortoise shell (Amblyomma sp. in Geochelone pardalis) (imaGe taken by Andrei Daniel Mihalca) Second row, riGht: Testudo graeca with doG bite marks (imaGe taken by Beate Pfau) Acknowledgements: The development of this manual would not have been possible without the help, support and guidance of many people. -

Contributo Scientifico: Secondo Workshop Internazionale

BOOK OF ABSTRACTS of the 2nd international workshop–conference “RESEARCH AND CONSERVATION OF EUROPEAN HERPETOFAUNA AND ITS ENVIRONMENT: BOMBINA BOMBINA, EMYS ORBICULARIS, AND CORONELLA AUSTRIACA” Belarus Belgium Denmark France Germany Italy Latvia Poland Russia Spain Ukraine www.life-herpetolatvia.biology.lv Daugavpils University, Institute of Ecology 2014 Book of abstracts of the 2nd International workshop–conference: Research and conservation of European herpetofauna and its environment: Bombina bombina, Emys orbicularis, and Coronella austriaca. Project LIFE-HerpetoLatvia, 14-15.08.2014. Daugavpils, Latvia: 42 p. The Project LIFE-HerpetoLatvia is co-financed by European Commission. Natura 2000. 'Natura 2000 - Europe's nature for you. The sites of Project are part of the European Natura 2000 Network. It has been designated because it hosts some of Europe's most threatened species and habitats. All 27 countries of the EU are working together through the Natura 2000 network to safeguard Europe's rich and diverse natural heritage for the benefit of all'. Scientific committee Academ., Dr. Arvids Barsevskis, Daugavpils University, Latvia; Dr. Victor Bakharev, Mozyr Pedagogical University, Belarus; PhD (Biol.) Vladimir Vladimirovich Bobrov, A.N. Severtsov Institute of Ecology and Evolution of the RAS, Russia; Dr. Andris Čeirāns, LIFE-HerpetoLatvia, University of Latvia, Latvia; Dr. Jean-Yves Georges, Institut Pluridisciplinaire Hubert Curien, Department of Ecology, Physiology and Ethology, France; Dr. Dario Ottonello, Cesbin srl, spin-off of Genoa University, Italy; Dr. Aija Pupiņa, LIFE-HerpetoLatvia, Latgales Zoo, Daugavpils University, Latvia; Dr. Artūrs Škute, Daugavpils University, Latvia; Dr. Nataļja Škute, Daugavpils University, Latvia; Dr. Wlodzimierz Wojtas, Instytut Biologii, Cracow Pedagogical University, Poland. Dr. Mihails Pupiņš, LIFE-HerpetoLatvia, Daugavpils University, Latvia. -

Demographic Consequences of Superabundance in Krefft's River

i The comparative ecology of Krefft’s River Turtle Emydura krefftii in Tropical North Queensland. By Dane F. Trembath B.Sc. (Zoology) Applied Ecology Research Group University of Canberra ACT, 2601 Australia A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Masters of Applied Science (Resource Management). August 2005. ii Abstract An ecological study was undertaken on four populations of Krefft’s River Turtle Emydura krefftii inhabiting the Townsville Area of Tropical North Queensland. Two sites were located in the Ross River, which runs through the urban areas of Townsville, and two sites were in rural areas at Alligator Creek and Stuart Creek (known as the Townsville Creeks). Earlier studies of the populations in Ross River had determined that the turtles existed at an exceptionally high density, that is, they were superabundant, and so the Townsville Creek sites were chosen as low abundance sites for comparison. The first aim of this study was to determine if there had been any demographic consequences caused by the abundance of turtle populations of the Ross River. Secondly, the project aimed to determine if the impoundments in the Ross River had affected the freshwater turtle fauna. Specifically this study aimed to determine if there were any difference between the growth, size at maturity, sexual dimorphism, size distribution, and diet of Emydura krefftii inhabiting two very different populations. A mark-recapture program estimated the turtle population sizes at between 490 and 5350 turtles per hectare. Most populations exhibited a predominant female sex-bias over the sampling period. Growth rates were rapid in juveniles but slowed once sexual maturity was attained; in males, growth basically stopped at maturity, but in females, growth continued post-maturity, although at a slower rate. -

Habitat Use, Size Structure and Sex Ratio of the Spot

Habitat use, size structure and sex ratio of the spot-legged turtle, Rhinoclemmys punctularia punctularia (Testudines: Geoemydidae), in Algodoal-Maiandeua Island, Pará, Brazil Manoela Wariss1, Victoria Judith Isaac2 & Juarez Carlos Brito Pezzuti1 1 Núcleo de Altos Estudos Amazônicos, Sala 01, Setor Profissional, Universidade Federal do Pará, Campus Universitário do Guamá, Rua Augusto Corrêa, nº 1 - CEP: 66.075-110, Belém, Pará, Brasil; [email protected], [email protected] 2 Laboratório de Biologia Pesqueira e Manejo de Recursos Aquáticos, Instituto de Ciências Biológicas, Universidade Federal do Pará, Av. Perimetral N° 2651, CEP 66077-830, Belém, Pará, Brasil; [email protected] Received 17-II-2011. Corrected 30-V-2011. Accepted 29-VII-2011. Abstract: Rhinoclemmys punctularia punctularia is a semi-aquatic chelonian found in Northern South America. We analyzed the habitat use, size structure and sex ratio of the species on Algodoal-Maiandeua Island, a pro- tected area on the Northeastern coast of the Brazilian state of Pará. Four distinct habitats (coastal plain lake, flooded forest “igapó”, interdunal lakes, and tidal channels) were surveyed during the rainy (March and April) and dry (August and September) seasons of 2009, using hoop traps. For the analysis of population structure, additional data were taken in March and August, 2008. A total of 169 individuals were captured in flooded forest (igapó), lakes of the coastal plain and, occasionally, in temporary pools. Capture rates were highest in the coastal plain lake, possibly due to the greater availability of the fruits that form part of the diet of R. p. punctularia. Of the physical-chemical variables measured, salinity appeared to be the only factor to have a significant negative effect on capture rates. -

New Records of Mesoclemmys Raniceps (Testudines, Chelidae) for the States of Amazonas, Pará and Rondônia, North Brazil, Including the Tocantins Basin

Herpetology Notes, volume 12: 283-289 (2019) (published online on 18 February 2019) New records of Mesoclemmys raniceps (Testudines, Chelidae) for the states of Amazonas, Pará and Rondônia, North Brazil, including the Tocantins basin Elizângela Silva Brito1,*, Rafael Martins Valadão2, Fábio Andrew G. Cunha3, Cristiane Gomes de Araújo4, Patrik F. Viana5, and Izaias Fernandes Médice6 Of the 58 species of living Chelidae (Rhodin et al., Among the rare species of the genus, Mesoclemmys 2017), 20 are known from Brazil (Costa and Bérnils, raniceps (Gray, 1856), a medium-sized freshwater turtle 2018). Of these, nine occur in the Amazon basin, (approximately 330 mm carapace length - CL; Rueda- including species of the genera Chelus, Mesoclemmys, Almonacid et al., 2007), inhabits streams and flooded Platemys, Phrynops and Rhinemys (Ferrara et al., 2017). forest, but can also be found in rivers, shallow lakes and The genus Mesoclemmys is the most diverse in Brazil, temporary pools in the forest (Vogt, 2008; Ferrara et and five of the eight species of Mesoclemmys in Brazil al., 2017). Mesoclemmys raniceps is relatively easy to occur within the Amazon basin (Souza, 2005; Ferrara identify, especially as an adult. Specimens of this species et al., 2017). Species of genus Mesoclemmys are rare have a large broad head, which is approximately one and inconspicuous when compared to other freshwater quarter of the length of the CL (head width between 23- turtles, and live in hard-to-reach places, to extent that 27%). The head is dark, but may show depigmentation in populations are rarely studied. This genus represents adults, resulting in a lighter color, generally in patches, the least studied among Amazonian turtles (Vogt, 2008; as shown in Figure 2 (af). -

Eastern Snake-Necked Turtle

Husbandry Manual for Eastern Snake-Necked Turtle Chelodina longicollis Reptilia: Chelidae Image Courtesy of Jacki Salkeld Author: Brendan Mark Host Date of Preparation: 04/06/06 Western Sydney Institute of TAFE - Richmond Course Name and Number: 1068 Certificate 3 - Captive Animals Lecturers: Graeme Phipps/Andrew Titmuss/ Jacki Salkeld CONTENTS 1. Introduction 4 2. Taxonomy 5 2.1 Nomenclature 5 2.2 Subspecies 5 2.3 Synonyms 5 2.4 Other Common Names 5 3. Natural History 6 3.1 Morphometrics 6 3.1.1 Mass and Basic Body Measurements 6 3.1.2 Sexual Dimorphism 6 3.1.3 Distinguishing Features 7 3.2 Distribution and Habitat 7 3.3 Conservation Status 8 3.4 Diet in the Wild 8 3.5 Longevity 8 3.5.1 In the Wild 8 3.5.2 In Captivity 8 3.5.3 Techniques Used to Determine Age in Adults 9 4. Housing Requirements 10 4.1 Exhibit/Enclosure Design 10 4.2 Holding Area Design 10 4.3 Spatial Requirements 11 4.4 Position of Enclosures 11 4.5 Weather Protection 11 4.6 Temperature Requirements 12 4.7 Substrate 12 4.8 Nestboxes and/or Bedding Material 12 4.9 Enclosure Furnishings 12 5. General Husbandry 13 5.1 Hygiene and Cleaning 13 5.2 Record Keeping 13 5.3 Methods of Identification 13 5.4 Routine Data Collection 13 6. Feeding Requirements 14 6.1 Captive Diet 14 6.2 Supplements 15 6.3 Presentation of Food 15 1 7. Handling and Transport 16 7.1 Timing of Capture and Handling 16 7.2 Capture and Restraint Techniques 16 7.3 Weighing and Examination 17 7.4 Release 17 7.5 Transport Requirements 18 7.5.1 Box Design 18 7.5.2 Furnishings 19 7.5.3 Water and Food 19 7.5.4 Animals Per Box 19 7.5.5 Timing of Transportation 19 7.5.6 Release from Box 19 8. -

Morphological Variation in the Brazilian Radiated Swamp Turtle Acanthochelys Radiolata (Mikan, 1820) (Testudines: Chelidae)

Zootaxa 4105 (1): 045–064 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) http://www.mapress.com/j/zt/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2016 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) http://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4105.1.2 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:DD15BE49-9A20-454E-A1FF-9E650C2A5A84 Morphological variation in the Brazilian Radiated Swamp Turtle Acanthochelys radiolata (Mikan, 1820) (Testudines: Chelidae) RAFAELLA C. GARBIN1,4,5, DEBORAH T. KARLGUTH2, DANIEL S. FERNANDES2,4, ROBERTA R. PINTO3,4 1Département de Géosciences, Université de Fribourg, Fribourg, 1700, Switzerland 2Departamento de Zoologia, Instituto de Biologia, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Ilha do Fundão, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, 21941-902, Brazil 3Universidade Católica de Pernambuco, Rua do Príncipe 526, Boa Vista, Recife, PE, 50050-900, Brazil 4Departamento de Vertebrados, Museu Nacional, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Quinta da Boa Vista, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, 20940-40, Brazil 5Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract The freshwater turtle Acanthochelys radiolata (Mikan, 1820) is endemic to the Atlantic Forest domain in Brazil and few studies have been done on the morphology, geographic variation and taxonomy of this species. In this paper we record the morphological variation, as well as sexual dimorphism and ontogenetic changes in A. radiolata throughout its distribution range. We analyzed 118 morphological characters from 41 specimens, both quantitative and qualitative, and performed statistical analyses to evaluate size and shape variation within our sample. Morphological analysis revealed that A. radi- olata is a polymorphic species, especially regarding color and shape. Two color patterns were recognized for the carapace and three for the plastron. -

New Distribution Records and Potentially Suitable Areas for the Threatened Snake-Necked Turtle Hydromedusa Maximiliani (Testudines: Chelidae) Author(S): Henrique C

New Distribution Records and Potentially Suitable Areas for the Threatened Snake-Necked Turtle Hydromedusa maximiliani (Testudines: Chelidae) Author(s): Henrique C. Costa, Daniella T. de Rezende, Flavio B. Molina, Luciana B. Nascimento, Felipe S.F. Leite, and Ana Paula B. Fernandes Source: Chelonian Conservation and Biology, 14(1):88-94. Published By: Chelonian Research Foundation DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.2744/ccab-14-01-88-94.1 URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.2744/ccab-14-01-88-94.1 BioOne (www.bioone.org) is a nonprofit, online aggregation of core research in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences. BioOne provides a sustainable online platform for over 170 journals and books published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/page/terms_of_use. Usage of BioOne content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. Chelonian Conservation and Biology, 2015, 14(1): 88–94 g 2015 Chelonian Research Foundation New Distribution Records and Potentially Suitable Areas for the Threatened Snake-Necked Turtle Hydromedusa maximiliani (Testudines: Chelidae) 1, 1 2,3 4 HENRIQUE C. COSTA *,DANIELLA T. DE REZENDE ,FLAVIO B. -

Conservación Y Tráfico De La Tortuga Matamata, Chelus Fimbriata

Lasso et al. Conservación y tráfico de la tortuga matamata, Chelus fimbriata (Schneider, 1783) en Colombia: un ejemplo del trabajo conjunto entre el Sistema Nacional Ambiental, ONG y academia Conservación y tráfico de la tortuga matamata, Chelus fimbriata (Schneider, 1783) en Colombia: un ejemplo del trabajo conjunto entre el Sistema Nacional Ambiental, ONG y academia Conservation and trafficking of the Matamata Turtle, Chelus fimbriata (Schneider, 1783) in Colombia: an example of joint efforts of the National Environmental System, one NGO, and academia Carlos A. Lasso, Fernando Trujillo, Monica A. Morales-Betancourt, Laura Amaya, Susana Caballero y Beiker Castañeda Resumen Se presentan los resultados de una iniciativa interinstitucional (Corpoamazonia, Corporinoquia, Instituto Humboldt, Universidad de Los Andes y Fundación Omacha), donde se verificó, con herramientas moleculares, que varios lotes de tortugas matamata (Chelus fimbriata) decomisadas en la ciudad de Leticia, departamento del Amazonas, Colombia, correspondían a ejemplares capturados en la Orinoquia y cuyo destino final era aparentemente Perú, como parte de una red de tráfico de fauna. Basados en este hallazgo, 2 corporaciones liberaron 400 individuos neonatos en el en el río Bita y la Reserva Natural Privada Bojonawi en el departamento del Vichada, Orinoquia colombiana. Se evidencia el tráfico de esta especie probablemente hacia Perú, donde la comercialización de tortugas es legal. Se recomienda el uso de protocolos de identificación genética para determinar y controlar la procedencia geográfica de tortugas decomisadas a futuro, como paso previo y necesario para su liberación. Palabras clave. Amazonas. Identificación molecular. Liberación de especies. Orinoquia. Tráfico de especies. Abstract We present the results of an interinstitutional initiative that verified the provenance of several groups of the Matamata Turtle (Chelus fimbriata), confiscated in the city of Leticia, department of Amazonas, Colombia, with molecular tools.