Acne and Its Management S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Azelaic Acid

Azelaic Acid (FINACEA) Topical Foam 15% National Drug Monograph August 2016 VA Pharmacy Benefits Management Services, Medical Advisory Panel, and VISN Pharmacist Executives The purpose of VA PBM Services drug monographs is to provide a focused drug review for making formulary decisions. Updates will be made when new clinical data warrant additional formulary discussion. Documents will be placed in the Archive section when the information is deemed to be no longer current. FDA Approval Information Description/Mechanism of Azelaic acid is a naturally occurring C9-dicarboxylic acid that is found in plants Action (such as whole grain cereals), animals and humans. Azelaic acid has antiinflammatory, antioxidative and antikeratinizing effects. In rosacea skin, azelaic acid decreases cathelicidin levels and kallikrein 5 (KLK5) activity and possibly inhibits toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) expression.1 A 15% gel formulation has been marketed for rosacea, and 20% cream has been available for acne vulgaris. The newer foam formulation consists of an oil- in-water emulsion and was designed to have a higher lipid content than the gel for dry and sensitive skin. Indication(s) Under Review Topical treatment of inflammatory papules and pustules of mild to moderate in This Document rosacea. Dosage Form(s) Under Foam, 15% Review REMS REMS No REMS Postmarketing Requirements See Other Considerations for additional REMS information Pregnancy Rating Category B Executive Summary Efficacy There have been no head-to-head trials comparing the foam and gel formulations of azelaic acid in terms of safety, tolerability and efficacy in the treatment of papulopustular (PP) rosacea.. In two major randomized clinical trials, azelaic acid foam produced small benefits over vehicle foam in achieving Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) treatment success (NNTs of 9.2 and 11.5) and in reducing inflammatory lesion counts. -

Pediatric and Adolescent Dermatology

Pediatric and adolescent dermatology Management and referral guidelines ICD-10 guide • Acne: L70.0 acne vulgaris; L70.1 acne conglobata; • Molluscum contagiosum: B08.1 L70.4 infantile acne; L70.5 acne excoriae; L70.8 • Nevi (moles): Start with D22 and rest depends other acne; or L70.9 acne unspecified on site • Alopecia areata: L63 alopecia; L63.0 alopecia • Onychomycosis (nail fungus): B35.1 (capitis) totalis; L63.1 alopecia universalis; L63.8 other alopecia areata; or L63.9 alopecia areata • Psoriasis: L40.0 plaque; L40.1 generalized unspecified pustular psoriasis; L40.3 palmoplantar pustulosis; L40.4 guttate; L40.54 psoriatic juvenile • Atopic dermatitis (eczema): L20.82 flexural; arthropathy; L40.8 other psoriasis; or L40.9 L20.83 infantile; L20.89 other atopic dermatitis; or psoriasis unspecified L20.9 atopic dermatitis unspecified • Scabies: B86 • Hemangioma of infancy: D18 hemangioma and lymphangioma any site; D18.0 hemangioma; • Seborrheic dermatitis: L21.0 capitis; L21.1 infantile; D18.00 hemangioma unspecified site; D18.01 L21.8 other seborrheic dermatitis; or L21.9 hemangioma of skin and subcutaneous tissue; seborrheic dermatitis unspecified D18.02 hemangioma of intracranial structures; • Tinea capitis: B35.0 D18.03 hemangioma of intraabdominal structures; or D18.09 hemangioma of other sites • Tinea versicolor: B36.0 • Hyperhidrosis: R61 generalized hyperhidrosis; • Vitiligo: L80 L74.5 focal hyperhidrosis; L74.51 primary focal • Warts: B07.0 verruca plantaris; B07.8 verruca hyperhidrosis, rest depends on site; L74.52 vulgaris (common warts); B07.9 viral wart secondary focal hyperhidrosis unspecified; or A63.0 anogenital warts • Keratosis pilaris: L85.8 other specified epidermal thickening 1 Acne Treatment basics • Tretinoin 0.025% or 0.05% cream • Education: Medications often take weeks to work AND and the patient’s skin may get “worse” (dry and red) • Clindamycin-benzoyl peroxide 1%-5% gel in the before it gets better. -

The Diagnosis and Management of Mild to Moderate Pediatric Acne Vulgaris

The Diagnosis and Management of Mild to Moderate Pediatric Acne Vulgaris Successful management of acne vulgaris requires a comprehensive approach to patient care. By Joseph B. Bikowski, MD s a chronic, inflammatory skin disorder affect- seek treatment, males tend to have more severe pre- ing susceptible pilosebaceous units of the face, sentations. Acne typically begins between seven and Aneck, shoulders, and upper trunk, acne pres- 10 years of age and peaks between the ages of 16-19 ents unique challenges for patients and clini- years. A majority of patients clear by 20-25 years of cians. Characterized by both non-inflammatory and age, however some patients continue to have acne inflammatory lesions, three types of acne have been beyond 40 years of age. So-called “adult acne,” per- identified: neonatal acne, infantile acne, and acne sisting beyond the early-to-mid 20s, is more common vulgaris; pediatric acne vulgaris is the focus of this in women than in men. Given the hormonal media- article. Successful management of mild to moderate tors involved, acne onset correlates better with acne vulgaris requires a comprehensive approach to pubertal age than with chronological age. patient care that emphasizes 1.) education, 2.) prop- er skin care, and 3.) targeted therapy aimed at the Take-Home Tips. Successful management of mild to moderate underlying pathogenic factors that contribute to acne vulgaris requires a comprehensive approach to patient care that acne. Early initiation of effective therapy is essential emphasizes 1.) education, 2.) proper skin care, and 3.) targeted to minimize the emotional impact of acne on a therapy aimed at underlying pathogenic factors that contribute to patient, improve clinical outcomes, and prevent acne. -

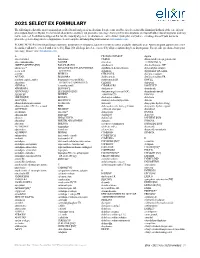

2021 SELECT EX FORMULARY the Following Is a List of the Most Commonly Prescribed Brand and Generic Medications

2021 SELECT EX FORMULARY The following is a list of the most commonly prescribed brand and generic medications. It represents an abbreviated version of the formulary list that is at the core of your prescription drug benefit plan. The list is not all-inclusive and does not guarantee coverage. Some preferred medications overlap with other clinical programs and may not be covered. In addition to drugs on this list, the majority of generic medications are covered under your plan and you are encouraged to ask your doctor to prescribe generic drugs whenever appropriate. Search complete formulary drug information at elixirsolutions.com. PLEASE NOTE: Preferred brand drugs may move to non-preferred status if a generic version becomes available during the year. Any medication approved to enter the market will not be covered until reviewed by Elixir. Not all drugs listed are covered by all prescription drug benefit programs. For specific questions about your coverage, please visit elixirsolutions.com. A B CILOXAN OINTMENT digoxin abacavir tablet balsalazide CIMDUO diltiazem ER (except generics for abacavir-lamivudine BAQSIMI cinacalcet CARDIZEM LA) ABILIFY MAINTENA [INJ] BASAGLAR [INJ] ciprofloxacin dimethyl fumarate DR* abiraterone* BD ULTRAFINE INSULIN SYRINGES ciprofloxacin-dexamethasone diphenoxylate-atropine acetic acid & NEEDLES citalopram dipyridamole ER-aspirin acitretin BELBUCA CITRANATAL divalproex sodium ACUVAIL BELSOMRA clarithromycin divalproex sodium ER acyclovir capsule, tablet benzonatate (except NDCs: clarithromycin ER DIVIGEL -

General Dermatology an Atlas of Diagnosis and Management 2007

An Atlas of Diagnosis and Management GENERAL DERMATOLOGY John SC English, FRCP Department of Dermatology Queen's Medical Centre Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust Nottingham, UK CLINICAL PUBLISHING OXFORD Clinical Publishing An imprint of Atlas Medical Publishing Ltd Oxford Centre for Innovation Mill Street, Oxford OX2 0JX, UK tel: +44 1865 811116 fax: +44 1865 251550 email: [email protected] web: www.clinicalpublishing.co.uk Distributed in USA and Canada by: Clinical Publishing 30 Amberwood Parkway Ashland OH 44805 USA tel: 800-247-6553 (toll free within US and Canada) fax: 419-281-6883 email: [email protected] Distributed in UK and Rest of World by: Marston Book Services Ltd PO Box 269 Abingdon Oxon OX14 4YN UK tel: +44 1235 465500 fax: +44 1235 465555 email: [email protected] © Atlas Medical Publishing Ltd 2007 First published 2007 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Clinical Publishing or Atlas Medical Publishing Ltd. Although every effort has been made to ensure that all owners of copyright material have been acknowledged in this publication, we would be glad to acknowledge in subsequent reprints or editions any omissions brought to our attention. A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library ISBN-13 978 1 904392 76 7 Electronic ISBN 978 1 84692 568 9 The publisher makes no representation, express or implied, that the dosages in this book are correct. Readers must therefore always check the product information and clinical procedures with the most up-to-date published product information and data sheets provided by the manufacturers and the most recent codes of conduct and safety regulations. -

Herb Lotions to Regrow Hair in Patients with Intractable Alopecia Areata Hideo Nakayama*, Ko-Ron Chen Meguro Chen Dermatology Clinic, Tokyo, Japan

Clinical and Medical Investigations Research Article ISSN: 2398-5763 Herb lotions to regrow hair in patients with intractable alopecia areata Hideo Nakayama*, Ko-Ron Chen Meguro Chen Dermatology Clinic, Tokyo, Japan Abstract The history of herbal medicine in China goes back more than 1,000 years. Many kinds of mixtures of herbs that are effective to diseases or symptoms have been transmitted from the middle ages to today under names such as Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) in China and Kampo in Japan. For the treatment of severe and intractable alopecia areata, such as alopecia universalis, totalis, diffusa etc., herb lotions are known to be effective in hair regrowth. Laiso®, Fukisin® in Japan and 101® in China are such effective examples. As to treat such cases, systemic usage of corticosteroid hormones are surely effective, however, considering their side effects, long term usage should be refrained. There are also these who should refrain such as small children, and patients with peptic ulcers, chronic infections and osteoporosis. AL-8 and AL-4 were the prescriptions removing herbs which are not allowed in Japanese Pharmacological regulations from 101, and salvia miltiorrhiza radix (SMR) is the most effective herb for hair growth, also the causation to produce contact sensitization. Therefore, the mechanism of hair growth of these herb lotions in which the rate of effectiveness was in average 64.8% on 54 severe intractable cases of alopecia areata, was very similar to DNCB and SADBE. The most recommended way of developing herb lotion with high ability of hairgrowth is to use SMR but its concentration should not exceed 2%, and when sensitization occurs, the lotion should be changed to Laiso® or Fukisin®, which do not contain SMR. -

CVS Formulary Drug Listing

January 2021 Updated 11/01/2020 Performance Drug List - Standard Control The CVS Caremark® Performance Drug List - Standard Control is a guide within select therapeutic categories for clients, plan members and health care providers. Generics should be considered the first line of prescribing. If there is no generic available, there may be more than one brand-name medicine to treat a condition. These preferred brand-name medicines are listed to help identify products that are clinically appropriate and cost-effective. Generics listed in therapeutic categories are for representational purposes only. This is not an all-inclusive list. This list represents brand products in CAPS, branded generics in upper- and lowercase Italics, and generic products in lowercase italics. PLAN MEMBER HEALTH CARE PROVIDER Your benefit plan provides you with a prescription benefit program Your patient is covered under a prescription benefit plan administered administered by CVS Caremark. Ask your doctor to consider by CVS Caremark. As a way to help manage health care costs, prescribing, when medically appropriate, a preferred medicine from authorize generic substitution whenever possible. If you believe a this list. Take this list along when you or a covered family member brand-name product is necessary, consider prescribing a brand name sees a doctor. on this list. Please note: Please note: • Your specific prescription benefit plan design may not cover • Generics should be considered the first line of prescribing. certain products or categories, regardless of their appearance in • The member's prescription benefit plan design may alter coverage this document. Products recently approved by the U.S. Food and of certain products or vary copay1 amounts based on the condition Drug Administration (FDA) may not be covered upon release being treated. -

Supply Issues Update for Primary and Secondary Care: September 2019

COMMERCIAL-SENSITIVE Supply Issues Update for Primary and Secondary Care: September 2019 This report has been produced by the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) Medicine Supply Team. We aim to update this report monthly to provide an update on current primary and secondary care medicine supply issues that we are working on. This information is confidential to the NHS; please do not upload to websites in the public domain. Please do share with relevant colleagues and networks. Where it has been stated ‘a clinical memo from UKMI will be published on the SPS website’, this will be found at the following URL: https://www.sps.nhs.uk/category/shortages-discontinuations-and-expiries/ Acetylcholine Chloride (Miochol-E) 20mg Contents powder and solvent for irrigation ..................8 New Issues ............................................................. 3 Aciclovir 500mg/1g injection .........................8 Injectables ......................................................... 3 Amikacin 500mg/2ml injection ......................8 Diamorphine 5mg injection ........................... 3 Emerade 500 microgram and 300 microgram Adrenaline 1 in 1000, 1ml ampoules ............. 4 adrenaline auto-injector (AAI) devices ..........8 Lanoxin (digoxin) 250mcg/ml injection ......... 4 EpiPen and EpiPen Junior ..............................9 Sayana Press (medroxyprogesterone acetate Erwinase injection ..........................................9 104mg) injection ............................................ 5 Haloperidol 5mg/ml injection ........................9 -

Disfiguring Ulcerative Neutrophilic Dermatosis Secondary To

RESIDENT HIGHLIGHTS IN COLLABORATION WITH COSMETIC SURGERY FORUM Disfiguring Ulcerative Neutrophilic Dermatosis Secondary to Doxycycline and Isotretinoin in an Bahman Sotoodian, MD Top 10 Fellow and Resident Adolescent Boy With Grant Winner at the 8th Cosmetic Surgery Forum Acne Conglobata Bahman Sotoodian, MD; Paul Kuzel, MD, FRCPC; Alain Brassard, MD, FRCPC; Loretta Fiorillo, MD, FRCPC copy accompanied by systemic symptoms including fever and leuko- RESIDENT cytosis. We report a challenging case of a 13-year-old adolescent PEARL boy who acutely developed hundreds of ulcerative plaques as well • Doxycycline and isotretinoin have been widely used as systemicnot symptoms after being treated with doxycycline and for treatment of inflammatory and nodulocystic acne. isotretinoin for acne conglobata. He was treated with prednisone, Although outstanding results can be achieved, para- dapsone, and colchicine and had to switch to cyclosporine to doxical worsening of acne while starting these medi- achieve relief from his condition. cations has been described. In patients with severeDo Cutis. 2017;100:E23-E26. acne (ie, acne conglobata), initiation of doxycycline and especially isotretinoin at regular dosages as the sole treatment can impose devastating risks on the patient. These patients are best treated with a combi- cne fulminans is an uncommon and debilitating nation of low-dose isotretinoin (at the beginning) with disease that presents as an acute eruption of nodular a moderate dose of steroids, which should be gradu- A and ulcerative acne lesions with associated systemic ally tapered while the isotretinoin dose is increased to symptoms.1,2 Although its underlying pathophysiology is 0.5 to 1 mg/kg once daily. -

Acne in Childhood: an Update Wendy Kim, DO; and Anthony J

FEATURE Acne in Childhood: An Update Wendy Kim, DO; and Anthony J. Mancini, MD cne is the most common chron- ic skin disease affecting chil- A dren and adolescents, with an 85% prevalence rate among those aged 12 to 24 years.1 However, recent data suggest a younger age of onset is com- mon and that teenagers only comprise 36.5% of patients with acne.2,3 This ar- ticle provides an overview of acne, its pathophysiology, and contemporary classification; reviews treatment op- tions; and reviews recently published algorithms for treating acne of differing levels of severity. Acne can be classified based on le- sion type (morphology) and the age All images courtesy of Anthony J. Mancini, MD. group affected.4 The contemporary Figure 1. Comedonal acne. This patient has numerous closed comedones (ie, “whiteheads”). classification of acne based on sev- eral recent reviews is addressed below. Acne lesions (see Table 1, page 419) can be divided into noninflammatory lesions (open and closed comedones, see Figure 1) and inflammatory lesions (papules, pustules, and nodules, see Figure 2). The comedone begins with Wendy Kim, DO, is Assistant Professor of In- ternal Medicine and Pediatrics, Division of Der- matology, Loyola University Medical Center, Chicago. Anthony J. Mancini, MD, is Professor of Pediatrics and Dermatology, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Ann and Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chi- cago. Address correspondence to: Anthony J. Man- Figure 2. Moderate mixed acne. In this patient, a combination of closed comedones, inflammatory pap- ules, and pustules can be seen. cini, MD, Division of Dermatology Box #107, Ann and Robert H. -

Table S1. Checklist for Documentation of Google Trends Research

Table S1. Checklist for Documentation of Google Trends research. Modified from Nuti et al. Section/Topic Checklist item Search Variables Access Date 11 February 2021 Time Period From January 2004 to 31 December 2019. Query Category All query categories were used Region Worldwide Countries with Low Search Excluded Volume Search Input Non-adjusted „Abrasion”, „Blister”, „Cafe au lait spots”, „Cellulite”, „Comedo”, „Dandruff”, „Eczema”, „Erythema”, „Eschar”, „Freckle”, „Hair loss”, „Hair loss pattern”, „Hiperpigmentation”, „Hives”, „Itch”, „Liver spots”, „Melanocytic nevus”, „Melasma”, „Nevus”, „Nodule”, „Papilloma”, „Papule”, „Perspiration”, „Petechia”, „Pustule”, „Scar”, „Skin fissure”, „Skin rash”, „Skin tag”, „Skin ulcer”, „Stretch marks”, „Telangiectasia”, „Vesicle”, „Wart”, „Xeroderma” Adjusted Topics: "Scar" + „Abrasion” / „Blister” / „Cafe au lait spots” / „Cellulite” / „Comedo” / „Dandruff” / „Eczema” / „Erythema” / „Eschar” / „Freckle” / „Hair loss” / „Hair loss pattern” / „Hiperpigmentation” / „Hives” / „Itch” / „Liver spots” / „Melanocytic nevus” / „Melasma” / „Nevus” / „Nodule” / „Papilloma” / „Papule” / „Perspiration” / „Petechia” / „Pustule” / „Skin fissure” / „Skin rash” / „Skin tag” / „Skin ulcer” / „Stretch marks” / „Telangiectasia” / „Vesicle” / „Wart” / „Xeroderma” Rationale for Search Strategy For Search Input The searched topics are related to dermatologic complaints. Because Google Trends enables to compare only five inputs at once we compared relative search volume of all topics with topic „Scar” (adjusted data). Therefore, -

EVIDENCE BASED UPDATE on the MANAGEMENT of ACNE Ep98 Jane Ravenscroft

PHARMACY UPDATE Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed: first published as 10.1136/adc.2004.071183 on 21 November 2005. Downloaded from EVIDENCE BASED UPDATE ON THE MANAGEMENT OF ACNE ep98 Jane Ravenscroft Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed 2005;90:ep98–ep101. doi: 10.1136/adc.2004.071183 cne is an extremely common condition, affecting up to 80% of adolescents. Many cases are mild and may be considered ‘‘physiological’’, but others can be very severe and lead to Apermanent scarring. Paediatricians will frequently encounter acne in their practice, and have an important role in identifying and advising patients who require treatment. This review focuses on the practical management of acne from a paediatric perspective, with an emphasis on relating treatment decisions to currently available evidence. Many clinical trials of acne treatment have been carried out in the last 25 years, but they are of variable quality. Hence, there are grey areas, where treatment has to be guided by consensus opinion or clinical experience until better evidence is available. CLINICAL FEATURES AND AETIOLOGY Acne is a disease of pilosebaceous follicles. Under the influence of androgens, usually around puberty, the sebaceous glands enlarge and produce excess sebum. At the same time, keratinocytes in the sebaceous duct proliferate and cause blockage. These events lead to comedone formation. As a secondary event, Propionibacterium acnes (P acnes) colonise the comedones causing inflammation, which leads to papules and pustules. Clinically, acne usually affects the face first, with the back and chest affected in more severe cases. The lesions seen are blackheads (open comedones), whiteheads (closed comedones), copyright.