Establishing a Cider Apple Orchard for Mechanized Management

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Apples Catalogue 2019

ADAMS PEARMAIN Herefordshire, England 1862 Oct 15 Nov Mar 14 Adams Pearmain is a an old-fashioned late dessert apple, one of the most popular varieties in Victorian England. It has an attractive 'pearmain' shape. This is a fairly dry apple - which is perhaps not regarded as a desirable attribute today. In spite of this it is actually a very enjoyable apple, with a rich aromatic flavour which in apple terms is usually described as Although it had 'shelf appeal' for the Victorian housewife, its autumnal colouring is probably too subdued to compete with the bright young things of the modern supermarket shelves. Perhaps this is part of its appeal; it recalls a bygone era where subtlety of flavour was appreciated - a lovely apple to savour in front of an open fire on a cold winter's day. Tree hardy. Does will in all soils, even clay. AERLIE RED FLESH (Hidden Rose, Mountain Rose) California 1930’s 19 20 20 Cook Oct 20 15 An amazing red fleshed apple, discovered in Aerlie, Oregon, which may be the best of all red fleshed varieties and indeed would be an outstandingly delicious apple no matter what color the flesh is. A choice seedling, Aerlie Red Flesh has a beautiful yellow skin with pale whitish dots, but it is inside that it excels. Deep rose red flesh, juicy, crisp, hard, sugary and richly flavored, ripening late (October) and keeping throughout the winter. The late Conrad Gemmer, an astute observer of apples with 500 varieties in his collection, rated Hidden Rose an outstanding variety of top quality. -

Diseases of Tree Fruit Apple: Diagnosis and Management

1 Diseases of Tree Fruit Apple: Diagnosis and Management Sara M. Villani June 22, 2017 Department of Entomology and Plant Pathology, NCSU [email protected] 2 Apple Disease Challenges in the S.E. • Several apple diseases to contend with Apple Disease Challenges in the S.E. 3 • Paucity of disease resistant cultivars – Breeding efforts focus on consumer preference – Usually single-disease resistance ‘Enterprise’ ‘Prima’ ‘Goldrush’ http://www.eatlikenoone.com/prima-apples.htm http://www.eatlikenoone.com/enterpris-apples.htm http://kuffelcreek.wordpress.com/ ‘William’s Pride’ ‘Liberty’ ‘Pristine’ http://www.eatlikenoone.com/pristine-apples.htm http://www.plant.photos.net/index.php?title=File:Apple_williams_pride.jpg http://www.plant.photos.net/index.php?title=File:Apple_libertye.jpg Apple Disease Challenges in the S.E. 4 • Warm, humid climate – Favorable for pathogen infection and disease development – Inadequate chilling hours: longer period of susceptibility to blossom infection Susceptible Host Biology and Conducive availability of Environment pathogen Apple Disease Challenges in the S.E. 5 • Maintaining practices of fungicide resistance management and maximum annual applications – Commercial apple growers in Hendersonville NC: Up to 24 fungicide applications in 2017! Multi-site Single-site Biologicals Protectants Fungicides Mancozeb Group 3: S.I.’s Bacillus spp. Captan Group 11: “Strobys” A. pullulans Copper Group 7: SDHIs Sulfur Group 1: “T-Methyl” ziram U12: Dodine Phosphorous Acid Confusing Fungicide Jargon 6 Fungicides are classified in a number of ways: 1. Chemical Group – e.g. triazoles, benzimidazoles 2. Biochemical Mode of Action (my preference, common in academia) – e.g. Demethylation inhibitor (DMI); Quinone-outside inhibitor (QoI) 3. Physical Mode of Action – e.g. -

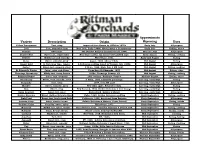

Variety Description Origin Approximate Ripening Uses

Approximate Variety Description Origin Ripening Uses Yellow Transparent Tart, crisp Imported from Russia by USDA in 1870s Early July All-purpose Lodi Tart, somewhat firm New York, Early 1900s. Montgomery x Transparent. Early July Baking, sauce Pristine Sweet-tart PRI (Purdue Rutgers Illinois) release, 1994. Mid-late July All-purpose Dandee Red Sweet-tart, semi-tender New Ohio variety. An improved PaulaRed type. Early August Eating, cooking Redfree Mildly tart and crunchy PRI release, 1981. Early-mid August Eating Sansa Sweet, crunchy, juicy Japan, 1988. Akane x Gala. Mid August Eating Ginger Gold G. Delicious type, tangier G Delicious seedling found in Virginia, late 1960s. Mid August All-purpose Zestar! Sweet-tart, crunchy, juicy U Minn, 1999. State Fair x MN 1691. Mid August Eating, cooking St Edmund's Pippin Juicy, crisp, rich flavor From Bury St Edmunds, 1870. Mid August Eating, cider Chenango Strawberry Mildly tart, berry flavors 1850s, Chenango County, NY Mid August Eating, cooking Summer Rambo Juicy, tart, aromatic 16th century, Rambure, France. Mid-late August Eating, sauce Honeycrisp Sweet, very crunchy, juicy U Minn, 1991. Unknown parentage. Late Aug.-early Sept. Eating Burgundy Tart, crisp 1974, from NY state Late Aug.-early Sept. All-purpose Blondee Sweet, crunchy, juicy New Ohio apple. Related to Gala. Late Aug.-early Sept. Eating Gala Sweet, crisp New Zealand, 1934. Golden Delicious x Cox Orange. Late Aug.-early Sept. Eating Swiss Gourmet Sweet-tart, juicy Switzerland. Golden x Idared. Late Aug.-early Sept. All-purpose Golden Supreme Sweet, Golden Delcious type Idaho, 1960. Golden Delicious seedling Early September Eating, cooking Pink Pearl Sweet-tart, bright pink flesh California, 1944, developed from Surprise Early September All-purpose Autumn Crisp Juicy, slow to brown Golden Delicious x Monroe. -

Apples: Organic Production Guide

A project of the National Center for Appropriate Technology 1-800-346-9140 • www.attra.ncat.org Apples: Organic Production Guide By Tammy Hinman This publication provides information on organic apple production from recent research and producer and Guy Ames, NCAT experience. Many aspects of apple production are the same whether the grower uses low-spray, organic, Agriculture Specialists or conventional management. Accordingly, this publication focuses on the aspects that differ from Published nonorganic practices—primarily pest and disease control, marketing, and economics. (Information on March 2011 organic weed control and fertility management in orchards is presented in a separate ATTRA publica- © NCAT tion, Tree Fruits: Organic Production Overview.) This publication introduces the major apple insect pests IP020 and diseases and the most effective organic management methods. It also includes farmer profiles of working orchards and a section dealing with economic and marketing considerations. There is an exten- sive list of resources for information and supplies and an appendix on disease-resistant apple varieties. Contents Introduction ......................1 Geographical Factors Affecting Disease and Pest Management ...........3 Insect and Mite Pests .....3 Insect IPM in Apples - Kaolin Clay ........6 Diseases ........................... 14 Mammal and Bird Pests .........................20 Thinning ..........................20 Weed and Orchard Floor Management ......20 Economics and Marketing ........................22 Conclusion -

Productivity and Economic Evaluation of Agroforestry Systems for Sustainable Production of Food and Non-Food Products

sustainability Article Productivity and Economic Evaluation of Agroforestry Systems for Sustainable Production of Food and Non-Food Products Lisa Mølgaard Lehmann 1 , Jo Smith 2, Sally Westaway 2, Andrea Pisanelli 3 , Giuseppe Russo 3, Robert Borek 4 , Mignon Sandor 5 , Adrian Gliga 5, Laurence Smith 6 and Bhim Bahadur Ghaley 1,* 1 Department of Plant and Environmental Sciences, University of Copenhagen, Højbakkegård Allé 30, 2630 Taastrup, Denmark; [email protected] 2 The Organic Research Centre, Elm Farm, Hamstead Marshall, Newbury RG20 0HR, UK; [email protected] (J.S.); [email protected] (S.W.) 3 National Research Council, Institute of Research on Terrestrial Ecosystems, Via Marconi 2, 05010 Porano, Italy; [email protected] (A.P.); [email protected] (G.R.) 4 Institute of Soil Science and Plant Cultivation—State Research Institute, Czartoryskich 8, 24-100 Puławy, Poland; [email protected] 5 University of Agricultural Sciences and Veterinary Medicine, Cluj-Napoca, Calea Manastur, 3-5, 400372 Cluj-Napoca, Romania; [email protected] (M.S.); [email protected] (A.G.) 6 School for Agriculture, Food and the Environment, the Royal Agricultural University, Cirencester, Gloucestershire GL7 6JS, UK; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +45-35333570 Received: 22 May 2020; Accepted: 30 June 2020; Published: 6 July 2020 Abstract: Agroforestry systems have multifunctional roles in enhancing agronomic productivity, co-production of diversity of food and non-food products and provision of ecosystem services. The knowledge of the performance of agroforestry systems compared with monoculture is scarce and scattered. Hence, the objective of the study was to analyze the agronomic productivity and economic viability of diverse agroforestry systems in Europe. -

Apple Orchard Information for Beginners

The UVM Apple Program: Extension and Research for the commercial tree fruit grower in Vermont and beyond... Our commitment is to provide relevant and timely horticultural, integrated pest management, marketing and economics information to commercial tree fruit growers in Vermont and beyond. If you have any questions or comments, please contact us. UVM Apple Team Members Dr. Lorraine Berkett, Faculty ([email protected] ) Terence Bradshaw, Research Technician Sarah Kingsley-Richards, Research Technician Morgan Cromwell, Graduate Student Apple Orchard Information for Beginners..... [The following material is from articles that appeared in the “For Beginners…” Horticultural section of the 1999 Vermont Apple Newsletter which was written by Dr. Elena Garcia. Please see http://orchard.uvm.edu/ for links to other material.] Websites of interest: UVM Apple Orchard http://orchard.uvm.edu/ UVM Integrated Pest Management (IPM) Calendar http://orchard.uvm.edu/uvmapple/pest/2000IPMChecklist.html New England Apple Pest Management Guide [use only for biological information] http://www.umass.edu/fruitadvisor/NEAPMG/index.htm Cornell Fruit Pages http://www.hort.cornell.edu/extension/commercial/fruit/index.html UMASS Fruit Advisor http://www.umass.edu/fruitadvisor/ 1/11/2007 Page 1 of 15 Penn State Tree Fruit Production Guide http://tfpg.cas.psu.edu/default.htm University of Wisconsin Extension Fruit Tree Publications http://learningstore.uwex.edu/Tree-Fruits-C85.aspx USDA Appropriate Technology Transfer for Rural Areas (ATTRA) Fruit Pages: http://www.attra.org/horticultural.html _____________________________________________________ Considerations before planting: One of the questions most often asked is, "What do I need to do to establish a small commercial orchard?" The success of an orchard is only as good as the planning and site preparation that goes into it. -

A Day in the Life of Your Data

A Day in the Life of Your Data A Father-Daughter Day at the Playground April, 2021 “I believe people are smart and some people want to share more data than other people do. Ask them. Ask them every time. Make them tell you to stop asking them if they get tired of your asking them. Let them know precisely what you’re going to do with their data.” Steve Jobs All Things Digital Conference, 2010 Over the past decade, a large and opaque industry has been amassing increasing amounts of personal data.1,2 A complex ecosystem of websites, apps, social media companies, data brokers, and ad tech firms track users online and offline, harvesting their personal data. This data is pieced together, shared, aggregated, and used in real-time auctions, fueling a $227 billion-a-year industry.1 This occurs every day, as people go about their daily lives, often without their knowledge or permission.3,4 Let’s take a look at what this industry is able to learn about a father and daughter during an otherwise pleasant day at the park. Did you know? Trackers are embedded in Trackers are often embedded Data brokers collect and sell, apps you use every day: the in third-party code that helps license, or otherwise disclose average app has 6 trackers.3 developers build their apps. to third parties the personal The majority of popular Android By including trackers, developers information of particular individ- and iOS apps have embedded also allow third parties to collect uals with whom they do not have trackers.5,6,7 and link data you have shared a direct relationship.3 with them across different apps and with other data that has been collected about you. -

We Make Delicious Cider from Freshly-Crushed Fruit How We Make It Happen the Zeffer Story

WE MAKE DELICIOUS CIDER FROM FRESHLY-CRUSHED FRUIT HOW WE MAKE IT HAPPEN THE ZEFFER STORY OUR JOURNEY BEGAN ON SAM’S PARENTS FARM IN 2009 WHEN SAM DECIDED TO TRY HIS WINE-MAKING HAND AT MAKING CIDER. AFTER EXTENSIVE RESEARCH WE KNEW THE STYLE OF CIDER WE LIKED BEST. NOT JUST ANY OLD ‘MADE FROM CONCENTRATE’ CIDER, WE WANTED TO MAKE REAL CIDER FROM REAL FRUIT WITH PATIENCE, CRAFT AND QUALITY. We knew that the final product would taste its best if we started with the best ingredients so we scoured the country to find specific apple and pear varieties from orchards around New Zealand. After long wintery nights crushing, an exploding fruit press, experimental brews and many hours spent hand bottling we had our first batch ready for release in the Spring of 2009. We sold it exclusively through our local Matakana Farmers market and were rewarded with great feedback, eager buyers and steady growth which ultimately allowed us to build our own cidery. And, while we are now the proud owners of a shiny new fruit press we remain faithful to our simple vision and ethos of making cider that we are both proud to put our name on and love to drink. Our ciders are fermented in small batches and made with minimal intervention that allows the natural flavours and true character to shine without the use of any artificial colours or sweeteners. We love what we do and we love that we get to share it with you. From the Team at Zeffer PRODUCT RANGE We make a tasty drop or two Or for something a little more fancy Red Apple Cider FRESH FROM THE ORCHARD Our Red Apple Cider captures the fresh flavour of the unique Mahana Red apples used to make it. -

Permaculture Orchard: Beyond Organic

The Permaculture Orchard: Beyond Organic Stefan Sobkowiak answers questions from people like you Compiled by Hugo Deslippe Formatted by James Samuel 1 Table Of Contents Introduction 3 Tree Care 4 Types Of Trees 13 Other Plants 22 Ground Cover 24 The Soil 26 Pests and other critters 30 Animals and friendly insects 32 Orchard Patterning 34 Permaculture concepts 35 Starting an orchard 37 Business questions 45 About Stefan and the Farm 51 Profiles 59 2 Introduction In June 2014, Stefan Sobkowiak and Olivier Asselin released an incredible movie called The Permaculture Orchard: Beyond Organic. Subsequently, Stefan was asked many questions about permaculture, orchards, fruit trees, etc. I decided to compile the questions about the permaculture orchard and the answers here. Most of the questions are taken from the following sources: The permies.com forum, in the growies / forest garden section. Les Fermes Miracle Farms Facebook page The Permaculture Orchard: Beyond Organic’s forum section Lastly, I want to specify that I claim no authorship or any credits at all for what follows, it’s all from elsewhere and only 2 or 3 of the questions are actually mine. If you have any questions for Stefan, especially after watching the movie: The Permaculture Orchard, Beyond Organic, please post them on the movie’s website forum. This is a long thread so to find what you are looking for, you might want to do CTRL F and type the term you want in the search box. It should work in your PDF reader too. Stefan answers multiples questions everyday so not all his answers are included. -

The Craft Cider Revival – Some Technical Considerations Andrew Lea 28/2/2007 1

The Craft Cider Revival – Some Technical Considerations Andrew Lea 28/2/2007 1 THE CRAFT CIDER REVIVAL ~ Some Technical Considerations Presentation to SWECA 28th February 2007 Andrew Lea SOME THINGS TO THINK ABOUT Orcharding and fruit selection Full juice or high gravity fermentations Yeast and sulphiting Keeving Malo-lactic maturation Style of finished product What is your overall USP? How are you differentiated? CRAFT CIDER IS NOW SPREADING Cidermaking was once widespread over the whole of Southern England There are signs that it may be returning eg Kent, Sussex and East Anglia So regional styles may be back in favour eg higher acid /less tannic in the East CHOICE OF CIDER FRUIT The traditional classification (Barker, LARS, 1905) Acid % ‘Tannin’ % Sweet < 0.45 < 0.2 Sharp > 0.45 < 0.2 Bittersharp > 0.45 > 0.2 Bittersweet < 0.45 > 0.2 Finished ~ 0.45 ~ 0.2 Cider CHOICE OF “VINTAGE QUALITY” FRUIT Term devised by Hogg 1886 Adopted by Barker 1910 to embrace superior qualities that could not be determined by analysis This is still true today! The Craft Cider Revival – Some Technical Considerations Andrew Lea 28/2/2007 2 “VINTAGE QUALITY” LIST (1988) Sharps / Bittersharps Dymock Red Kingston Black Stoke Red Foxwhelp Browns Apple Frederick Backwell Red Bittersweets Ashton Brown Jersey Harry Masters Jersey Dabinett Major White Jersey Yarlington Mill Medaille d’Or Pure Sweets Northwood Sweet Alford Sweet Coppin BLENDING OR SINGLE VARIETALS? Blending before fermentation can ensure good pH control (< 3.8) High pH (bittersweet) juices prone to infection Single varietals may be sensorially unbalanced unless ameliorated with dilution or added acid RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN pH AND TITRATABLE ACID IS NOT EXACT Most bittersweet juices are > pH 3.8 or < 0.4% titratable acidity. -

Brown Snout’ Specialty Cider Apple U.S

most popular alcoholic beverage made Yield, Labor, and Fruit and Juice Quality andconsumedintheUnitedStates; Characteristics of Machine and Hand-harvested however, by the early 1900s, cider had essentially disappeared from ‘Brown Snout’ Specialty Cider Apple U.S. markets (Proulx and Nichols, 1997). The rapid decline of cider 1 was due to a combination of factors, Carol A. Miles and Jaqueline King primarily a high influx of German and eastern European immigrants who ADDITIONAL INDEX WORDS. fruit storage, hard cider, harvest labor, Malus ·domestica, preferred beer, and many farmers mechanical fruit harvest, over-the-row harvester who were sympathetic to the Tem- perance Movement cut down their SUMMARY. In this 2-year study of ‘Brown Snout’ specialty cider apple apple trees (Watson, 1999). (Malus ·domestica) grafted onto Malling 27 (M.27) and East Malling/Long Ashton Cider is currently seeing a revival 9, we compared weight of total harvested fruit, labor hours for harvest, tree and fruit damage, and fruit and juice quality characteristics for machine and hand harvest. in the United States and although it Machine harvest was with an over-the-row small fruit harvester. There were no only accounts for 1% of the alcoholic significant differences due to rootstock; however, there were differences between beverage market, it is the fastest years for most measurements. Weight of harvested fruit did not differ because of growing alcohol market segment, harvest method; however, harvest efficiency was 68% to 72% for machine pick and with 54% increase in production each 85% to 89% for machine pick D clean-up weight (fruit left on trees and fruit year from 2007 to 2012 (Morton, knocked to the ground during harvest) as compared with hand harvest. -

Commercial Aquaponics Case Study #3: Economic Analysis of the University of the Virgin Islands Commercial Aquaponics System AEC 2015-18

Commercial Aquaponics Case Study #3: Economic Analysis of the University of the Virgin Islands Commercial Aquaponics System AEC 2015-18 This case study is the third of a series of three total case studies that analyzes the economics behind three different commercial aquaponics systems. Each case study will be released in this draft form to make the information available. The final report for this project will include the information from these three case studies, an overall analysis, and the summary of a commercial aquaponics industry survey. Authors: Kevin Heidemann Department of Agricultural Economics University of Kentucky tel: (502) 219-6301 e-mail: [email protected] Donald Bailey University of the Virgin Islands tel: (340) 692-403 e-mail: [email protected] Editors: R. Charlie Shultz Aquaponics Researcher Lethbridge College, Canada e-mail: [email protected] This project was funded by Southern Sustainable Agriculture Research & Education (SARE) through a Graduate Student Grant under the award number 3048110880. This publication has not been reviewed by an official departmental committee. The ideas presented and the positions taken are solely those of the author(s) and do not represent the official position of the Department of Agricultural Economics, the College of Agriculture, Food and Environment or The University of Kentucky. Questions should be directed to the author(s). Introduction to the UVI Agricultural Experiment Station & Background Info The University of the Virgin Islands’ Agricultural Experiment Station is located in beautiful St. Croix of the U.S. Virgin Islands. This is where the world renowned commercial-scale aquaponics system developed by the University of the Virgin Islands remains.