The Luthuli Detachment and the Wankie Campai

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download This Report

Military bases and camps of the liberation movement, 1961- 1990 Report Gregory F. Houston Democracy, Governance, and Service Delivery (DGSD) Human Sciences Research Council (HSRC) 1 August 2013 Military bases and camps of the liberation movements, 1961-1990 PREPARED FOR AMATHOLE DISTRICT MUNICIPALITY: FUNDED BY: NATIONAL HERITAGE COUNCI Table of Contents Acronyms and Abbreviations ..................................................................................................... ii Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................... iii Chapter 1: Introduction ...............................................................................................................1 Chapter 2: Literature review ........................................................................................................4 Chapter 3: ANC and PAC internal camps/bases, 1960-1963 ........................................................7 Chapter 4: Freedom routes during the 1960s.............................................................................. 12 Chapter 5: ANC and PAC camps and training abroad in the 1960s ............................................ 21 Chapter 6: Freedom routes during the 1970s and 1980s ............................................................. 45 Chapter 7: ANC and PAC camps and training abroad in the 1970s and 1980s ........................... 57 Chapter 8: The ANC’s prison camps ........................................................................................ -

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report: Volume 2

VOLUME TWO Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report The report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was presented to President Nelson Mandela on 29 October 1998. Archbishop Desmond Tutu Ms Hlengiwe Mkhize Chairperson Dr Alex Boraine Mr Dumisa Ntsebeza Vice-Chairperson Ms Mary Burton Dr Wendy Orr Revd Bongani Finca Adv Denzil Potgieter Ms Sisi Khampepe Dr Fazel Randera Mr Richard Lyster Ms Yasmin Sooka Mr Wynand Malan* Ms Glenda Wildschut Dr Khoza Mgojo * Subject to minority position. See volume 5. Chief Executive Officer: Dr Biki Minyuku I CONTENTS Chapter 1 Chapter 6 National Overview .......................................... 1 Special Investigation The Death of President Samora Machel ................................................ 488 Chapter 2 The State outside Special Investigation South Africa (1960-1990).......................... 42 Helderberg Crash ........................................... 497 Special Investigation Chemical and Biological Warfare........ 504 Chapter 3 The State inside South Africa (1960-1990).......................... 165 Special Investigation Appendix: State Security Forces: Directory Secret State Funding................................... 518 of Organisations and Structures........................ 313 Special Investigation Exhumations....................................................... 537 Chapter 4 The Liberation Movements from 1960 to 1990 ..................................................... 325 Special Investigation Appendix: Organisational structures and The Mandela United -

This Is an Authorized Facsimile, Made from the Microfilm This Is

This is an authorized facsimile, made from the microfilm This is an authorized facsimile, made from the microfilm master copy of the original dissertation or master thesis published by UMI. The bibliographic information for this thesis is contained in UMI's Dissertation Abstracts database, the only central source for accessing almost every doctoral dissertation accepted in North America since 1861. UMI Dissertation Services A Bell & Howell Company 300 N. Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 1-800-521-0600 313-761-4700 Printed in 1996 by xerographic process on acid-free paper DPGT The African National Congress in Exile: Strategy and Tactics 1960-1993 by Dale Thomas McKinley A Dissertation submitted to the faculty of The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Political Science. Chapel Hill 1995 Approved by: r n2 Advisor ____ Reader Iw'iwC "Reader U4I Number: 9538444 324.268 083 MCKI 01 1 0 II I 01 651 021 UNI Microform 9538444 Copyright 1995, by UMI Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. UMI 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, HI 48103 Kf IP INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The qualty of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. -

Who Is Governing the ''New'' South Africa?

Who is Governing the ”New” South Africa? Marianne Séverin, Pierre Aycard To cite this version: Marianne Séverin, Pierre Aycard. Who is Governing the ”New” South Africa?: Elites, Networks and Governing Styles (1985-2003). IFAS Working Paper Series / Les Cahiers de l’ IFAS, 2006, 8, p. 13-37. hal-00799193 HAL Id: hal-00799193 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00799193 Submitted on 11 Mar 2013 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Ten Years of Democratic South Africa transition Accomplished? by Aurelia WA KABWE-SEGATTI, Nicolas PEJOUT and Philippe GUILLAUME Les Nouveaux Cahiers de l’IFAS / IFAS Working Paper Series is a series of occasional working papers, dedicated to disseminating research in the social and human sciences on Southern Africa. Under the supervision of appointed editors, each issue covers a specifi c theme; papers originate from researchers, experts or post-graduate students from France, Europe or Southern Africa with an interest in the region. The views and opinions expressed here remain the sole responsibility of the authors. Any query regarding this publication should be directed to the chief editor. Chief editor: Aurelia WA KABWE – SEGATTI, IFAS-Research director. -

SOUTH AFRICAN POLITICAL EXILE in the UNITED KINGDOM Al50by Mark Israel

SOUTH AFRICAN POLITICAL EXILE IN THE UNITED KINGDOM Al50by Mark Israel INTERNATIONAL VICTIMOLOGY (co-editor) South African Political Exile in the United Kingdom Mark Israel SeniorLecturer School of Law TheFlinders University ofSouth Australia First published in Great Britain 1999 by MACMILLAN PRESS LTD Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS and London Companies and representatives throughout the world A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978-1-349-14925-4 ISBN 978-1-349-14923-0 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-349-14923-0 First published in the United States of Ameri ca 1999 by ST. MARTIN'S PRESS, INC., Scholarly and Reference Division. 175 Fifth Avenue. New York. N.Y. 10010 ISBN 978-0-312-22025-9 Library of Congre ss Cataloging-in-Publication Data Israel. Mark. 1965- South African political exile in the United Kingdom / Mark Israel. p. cm. Include s bibliographical references and index . ISBN 978-0-312-22025-9 (cloth) I. Political refugees-Great Britain-History-20th century. 2. Great Britain-Exiles-History-20th century. 3. South Africans -Great Britain-History-20th century. I. Title . HV640.5.S6I87 1999 362.87'0941-dc21 98-32038 CIP © Mark Israel 1999 Softcover reprint of the hardcover Ist edition 1999 All rights reserved . No reprodu ction. copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No paragraph of this publicat ion may be reproduced. copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provision s of the Copyright. Design s and Patents Act 1988. or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency . -

The Role and Application of the Union Defence Force in the Suppression of Internal Unrest, 1912 - 1945

THE ROLE AND APPLICATION OF THE UNION DEFENCE FORCE IN THE SUPPRESSION OF INTERNAL UNREST, 1912 - 1945 Andries Marius Fokkens Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Military Science (Military History) at the Military Academy, Saldanha, Faculty of Military Science, Stellenbosch University. Supervisor: Lieutenant Colonel (Prof.) G.E. Visser Co-supervisor: Dr. W.P. Visser Date of Submission: September 2006 ii Declaration I, the undersigned, hereby declare that the work contained in this thesis is my own original work and that I have not previously submitted it, in its entirety or in part, to any university for a degree. Signature:…………………….. Date:………………………….. iii ABSTRACT The use of military force to suppress internal unrest has been an integral part of South African history. The European colonisation of South Africa from 1652 was facilitated by the use of force. Boer commandos and British military regiments and volunteer units enforced the peace in outlying areas and fought against the indigenous population as did other colonial powers such as France in North Africa and Germany in German South West Africa, to name but a few. The period 1912 to 1945 is no exception, but with the difference that military force was used to suppress uprisings of white citizens as well. White industrial workers experienced this military suppression in 1907, 1913, 1914 and 1922 when they went on strike. Job insecurity and wages were the main causes of the strikes and militant actions from the strikers forced the government to use military force when the police failed to maintain law and order. -

Trc-Media-Sapa-2000.Pdf

GRAHAMSTOWN Jan 5 Sapa THREE OF DE KOCK'S CO-ACCUSED TO CHALLENGE TRC DECISION Three former security branch policemen plan to challenge the Truth and Reconciliation Commission's decision to refuse them and seven of their former colleagues, including Eugene de Kock, amnesty for the 1989 murder of four policemen. De Kock, Daniel Snyman, Nicholaas Janse Van Rensburg, Gerhardus Lotz, Jacobus Kok, Wybrand Du Toit, Nicolaas Vermeulen, Marthinus Ras and Gideon Nieuwoudt admitted responsibility for the massive car bomb which claimed the lives of Warrant Officer Mbalala Mgoduka, Sergeant Amos Faku, Sergeant Desmond Mpipa and an Askari named Xolile Shepherd Sekati. The four men died when a bomb hidden in the police car they were travelling in was detonated in a deserted area in Motherwell, Port Elizabeth, late at night in December 1989. Lawyer for Nieuwoudt, Lotz and Van Rensburg, Francois van der Merwe said he would shortly give notice to the TRC of their intention to take on review the decision to refuse the nine men amnesty. He said the judgment would be taken on review in its entirety, and if it was overturned by the court, the TRC would once again have to apply its mind to the matter in respect of all nine applicants. The applicants had been "unfairly treated", he said and the judges had failed to properly apply their mind to the matter. The amnesty decision was split, with Acting Judge Denzil Potgieter and Judge Bernard Ngoepe finding in the majority decision that the nine men did not qualify for amnesty as the act was not associated with a political objective and was not directed against members of the ANC or other liberation movements. -

ACTION NEWS: FALL 1990 Number 30 ACTION

AMERICAN COMMITIEE ON AFRICA ACTION NEWS: FALL 1990 Number 30 ACTION 198 Broadway • New York, NY 10038 • (212) 962-1210 A Hero~ Welcome o o OJ OJ < c: c:< < < ~. ~. o ~ OJco :::J N Nelson Mandela's tour of the United States created a groundswell of support for the democratic movement in South Africa. Everywhere he went, record breaking crowds and high-ranking officials welcomed him and his message to Keep the Pressure On Apartheid. Here we have captured some ofthe events in New York City, first stop on his tour. Above left, ANC Deputy President Nelson Mandela addresses National Activists Briefing. Left to right: Aubrey McCutcheon, Executive Director, Washington Office on Africa; Lindiwe Mabuza, ANC Chief Representative to the U.s.; Nelson Mandela; jennifer Davis; Tebogo Mafole, ANC Chief Representative to the U.N.; jerry Herman, Director Southern Africa Program, American Friends'Service Committee. Middle left, Mayor Dinkins presents Mr. Mandela with the keys to the city on the steps of New York City Hall. Bottom left, a ticker tape parade passes ACOA office in lower Manhattan welcoming the Mandelas to the u.s. on june 20, 1990. The large truck in the foreground housed the Mandelas, Mayor Dinkins and Gov. Cuomo during the parade. ACONs jennifer Davis served on the New York Nelson Mandela Welcome Commit tee. Pictured above she introduces Nelson Mandela to a meeting of grassroots activists (see story). ACOA also helped to organize the Yankee Stadium Rally and the event for women leadership with Winnie Mandela. COSATU Leader Votes Cyril Ramaphosa, General Secre tary of South Africa's National Union on Mine Workers (NUM) visited the u.s. -

We Were Cut Off from the Comprehension of Our Surroundings

Black Peril, White Fear – Representations of Violence and Race in South Africa’s English Press, 1976-2002, and Their Influence on Public Opinion Inauguraldissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Philosophischen Fakultät der Universität zu Köln vorgelegt von Christine Ullmann Institut für Völkerkunde Universität zu Köln Köln, Mai 2005 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The work presented here is the result of years of research, writing, re-writing and editing. It was a long time in the making, and may not have been completed at all had it not been for the support of a great number of people, all of whom have my deep appreciation. In particular, I would like to thank Prof. Dr. Michael Bollig, Prof. Dr. Richard Janney, Dr. Melanie Moll, Professor Keyan Tomaselli, Professor Ruth Teer-Tomaselli, and Prof. Dr. Teun A. van Dijk for their help, encouragement, and constructive criticism. My special thanks to Dr Petr Skalník for his unflinching support and encouraging supervision, and to Mark Loftus for his proof-reading and help with all language issues. I am equally grateful to all who welcomed me to South Africa and dedicated their time, knowledge and effort to helping me. The warmth and support I received was incredible. Special thanks to the Burch family for their help settling in, and my dear friend in George for showing me the nature of determination. Finally, without the unstinting support of my two colleagues, Angelika Kitzmantel and Silke Olig, and the moral and financial backing of my family, I would surely have despaired. Thank you all for being there for me. We were cut off from the comprehension of our surroundings; we glided past like phantoms, wondering and secretly appalled, as sane men would be before an enthusiastic outbreak in a madhouse. -

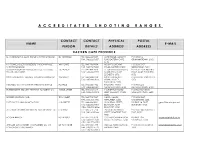

Accreditated Shooting Ranges

A C C R E D I T A T E D S H O O T I N G R A N G E S CONTACT CONTACT PHYSICAL POSTAL NAME E-MAIL PERSON DETAILS ADDRESS ADDRESS EASTERN CAPE PROVINCE D J SURRIDGE T/A ALOE RIDGE SHOOTING RANGE DJ SURRIDGE TEL: 046 622 9687 ALOE RIDGE MANLEY'S P O BOX 12, FAX: 046 622 9687 FLAT, EASTERN CAPE, GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 6140 K V PEINKE (SOLE PROPRIETOR) T/A BONNYVALE WK PEINKE TEL: 043 736 9334 MOUNT COKE KWT P O BOX 5157, SHOOTING RANGE FAX: 043 736 9688 ROAD, EASTERN CAPE GREENFIELDS, 5201 TOMMY BOSCH AND ASSOCIATES CC T/A LOCK, T C BOSCH TEL: 041 484 7818 51 GRAHAMSTAD ROAD, P O BOX 2564, NOORD STOCK AND BARREL FAX: 041 484 7719 NORTH END, PORT EINDE, PORT ELIZABETH, ELIZABETH, 6056 6056 SWALLOW KRANTZ FIREARM TRAINING CENTRE CC WH SCOTT TEL: 045 848 0104 SWALLOW KRANTZ P O BOX 80, TARKASTAD, FAX: 045 848 0103 SPRING VALLEY, 5370 TARKASTAD, 5370 MECHLEC CC T/A OUTSPAN SHOOTING RANGE PL BAILIE TEL: 046 636 1442 BALCRAIG FARM, P O BOX 223, FAX: 046 636 1442 GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 BUTTERWORTH SECURITY TRAINING ACADEMY CC WB DE JAGER TEL: 043 642 1614 146 BUFFALO ROAD, P O BOX 867, KING FAX: 043 642 3313 KING WILLIAM'S TOWN, WILLIAM'S TOWN, 5600 5600 BORDER HUNTING CLUB TE SCHMIDT TEL: 043 703 7847 NAVEL VALLEY, P O BOX 3047, FAX: 043 703 7905 NEWLANDS, 5206 CAMBRIDGE, 5206 EAST CAPE PLAINS GAME SAFARIS J G GREEFF TEL: 046 684 0801 20 DURBAN STREET, PO BOX 16, FORT [email protected] FAX: 046 684 0801 BEAUFORT, FORT BEAUFORT, 5720 CELL: 082 925 4526 BEAUFORT, 5720 ALL ARMS FIREARM ASSESSMENT AND TRAINING CC F MARAIS TEL: 082 571 5714 -

When the ANC and the SACP Created Umkhonto We Sizwe In

When the ANC and the SACP created Umkhonto we SIzwe in 1961 to take up arms against the State for the attainment of basic political rights, few people could have imagIned that the predictions made by the British Priae Minister, Harold Macmillan, in Cape Town on 3 February 1960, would become a reality in less than thIrty years. What he told Parliament and the world at large on that day was that "the wind of change" was blowing throughout the African continent and "whether we like it or not this growth of national consciousness is a political fact. We must all accept it as a fact and our national policies must take account of It."(1) To the leaders of the South African government and to most White South Africans at the time Macmillan was not seen as a visionary but rather as a British politician interfering in South Africa's internal affairs. lor the government of Dr H.l. Verwoerd, with its strong belief in racial segregation and White domination, to accept the possibility of White Afrikaner nationalism capitulating to African nationalism was inconceivable. To Verwoerd, Black, but particularly African, political aspirations had no future in a South Africa under White rule. lor anyone to suggest otherwise or.to promote Black political rights, in a multi-racial democracy, particularly through extra-Parliamentary means, was to attack government policy and the right of Whites to rUle. Thus any demand by Blacks for equal political rights, with Whites, in a unItary state, whether peaceful or not, was outrightly re1ectd by the South African government, who banned both the PAC and the ANC in 1960 when, it thought, these organIzatIons had become too radical In their demands. -

Vladimir Shubin on Soldiers in a Storm. the Armed Forces in South

Philip Frankel. Soldiers in a Storm. The Armed Forces in South Africa's Democratic Transition. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press, 2000. xvi + 247 pp. $65.00, paper, ISBN 978-0-8133-3747-0. Reviewed by Vladimir Shubin Published on H-SAfrica (April, 2001) Phillip Frankel, of the Department of Political 'vulnerable' for criticism. For example, Frankel Science, University of the Witwatersrand, has begins this chapter with 'Prelude: Talks about published a book on the most crucial problem of Talks, 1991-1993'. However, in this reviewer's South Africa's transition to democracy, i.e. on the opinion, the 'talks about talks' stage preceded this transformation and integration of the country's period, and talks were conducted through several armed forces. To a large extent Frankel's book is channels from the mid-1980s. Moreover, it was an 'off-spring' of the project on the history of the during the late 1980s when the ANC top leader‐ national armed forces in the period 1990-1996, ship began receiving signals from the SADF high‐ commissioned by the new South African National est echelons on the urgency of a political settle‐ Defence Force (SADF), which however remained ment. (Frankel does write that 'there is some evi‐ 'internal' and therefore inaccessible to a broad dence to suggest informal discussions occurred reading public. Fortunately, however, Frankel had between individuals from the South African mili‐ permission to use material from military archives tary and MK as early as ten to ffteen years before for his 'public' work as well. (p.2)', however he does not disclose the origin of The frst chapter of the book - Negotiation: this claim).