Lake Forest and the Progressive Era

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

North Shore Region

2013vg_Maps:Layout 1 9/16/2013 5:51 PM Page 1 ABCDEFGH I J KLMNOPQR Ⅵ1 Best Western University Plaza 1 DEERFIELD ROAD Ⅵ2 Comfort Inn & Suites HIGHLAND Conference Center DEERFIELD PARK 49 MILWAUKEE RAVINIA Ⅵ3 Courtyard Chicago 2 NORTHBROOK Glenview/Northbrook LAKE COOK ROAD COURT Ⅵ4 Crowne Plaza Chicago-Northbrook 49 CHICAGO BOTANIC GARDEN Ⅵ5 METRA DoubleTree by Hilton Hotel and 3 Conference Center DUNDEE ROAD Chicago-North Shore METRA LAKE MICHIGAN UNION PACIFIC 15 NORTH LINE Ⅵ6 The Glen Club 4 N. MILWAUKEE AVENUE TO KENOSHA 294 Northbrook GLENCOE Ⅵ7 Hampton Inn & Suites Chicago North Shore Ⅵ8 Hilton Chicago/Northbrook 5 CHICAGO TOWER ROAD EXECUTIVE Ⅵ9 Hilton Garden Inn Chicago AIRPORT 49 North Shore/Evanston 17 Winnetka SHERIDAN ROAD 20 WILLOW ROAD GREEN BAY ROAD 6 18 Ⅵ10 Hilton Orrington/Evanston 2 8 19 WILLOW ROAD Ⅵ 4 11 Holiday Inn North Shore METRA NORTHFIELD Ⅵ Prospect 6 ROAD WAUKEGAN 12 The Homestead Evanston 7 KOHL CHILDREN’S MUSEUM Ⅵ13 The Margarita European Inn Heights 3 KENILWORTH Ⅵ The Glen 14 Motel 6 Chicago North/Glenview 14 Town Center WAGNER FARM LAKE AVENUE Ⅵ15 Renaissance Chicago 8 LAKE AVENUE BAHÁ’Í TEMPLE METRA/ WILMETTE North Shore Hotel 21 AMTRAK LINDEN CTA PURPLE LINE Ⅵ16 Rodeway Inn 49 ABT Ⅵ17 9 ELECTRONICS Glenview Sheraton Chicago/Northbrook WESTFIELD OLD ORCHARD OLD ORCHARD ROAD Evanston GROSSE POINT Ⅵ18 LIGHTHOUSE Sherwood Inn & Suites 7 CENTRAL 294 ILLINOIS HOLOCAUST BOULEVARD SKOKIE Ⅵ19 MUSEUM & EDUCATION CENTER Staybridge Suites Hotel Glenview 10 GOLF ROAD NOYES 5 NORTHWESTERN Ⅵ20 Super 8 Prospect METRA FOSTER 10 UNIVERSITY MILWAUKEE NORTH SHORE CENTER 9 Heights/Northbrook DISTRICT NORTH LINE 16 FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS TO FOX LAKE IN SKOKIE DAVIS CRAWFORD AVENUE CRAWFORD 12 Ⅵ21 DEMPSTER STREET 13 1 Wyndham Glenview Suites 11 DEMPSTER DEMPSTER STREET CHICAGO AVENUE CHARLES GATES DAWES HOUSE N. -

Illinois Department of Public Health Division of Health Care Facilities and Programs Health Facilities Directory Home Services Agency

Illinois Department of Public Health Division of Health Care Facilities and Programs Health Facilities Directory Home Services Agency City Facility Name Facility Address County Zip Contact Person Phone # License # Peoria Lutheran Social Services of Illinois 3000 W. Rohmann Peoria 61604 Marilyn Elliott (847) 635-4600 3000541 Addison Dad & Kids, LLC - DBA Comfort Keepers 221 East Lake Street, Suite 212 Du Page 60101 Melissa Watters (630) 834-8366 3000180 Addison Worry-Free Home Care, Inc. 221 E. Lake St., Suite 107 Cook 60101 Fatema Rehman Mirza (630) 605-6184 3000669 Aledo Mercer County Health Dept.-Home Services 305 NW 7th Street Mercer 61231 Jennifer Hamerlinck (309) 582-3759 3000547 Program Algonquin Castle Ventures, Inc. - DBA Right at Home #48 409 South Main Street Mc Henry 60102 Jeanette Palmer (847) 458-8656 3000288 Alton Absolute Health Care Services, LLC 4124 Alby Street Madison 62002 Debra L. Ross (618) 466-1010 3000569 Alton BJC Home Care Services 3535 College Avenue, Suite B Madison 62002 Diane Straub (618) 463-7541 3000371 Alton HHL Holding Company LLC - DBA Home Helpers 200 W. 3rd Street, Suite 712 Madison 62002 William Haug (618) 462-2762 3000415 Alton Senior Services Plus, Inc. 2603 N. Rodgers Ave. Madison 62002 Jonathan Becker (618) 462-1391 3000432 Arlington Heights 733 Beach Walk, Inc. - DBA Home Helpers & 726 S. Cleveland Avenue Du Page 60005 Christopher L. Gerardi (630) 240-9107 3000538 Direct Link 58424 Arlington Heights Absolute Home Care, LLC 855 E. Golf Road, Suite 2132 Cook 60005 Fina R. Javier (224) 795-7952 3000590 Arlington Heights Caring Hearts Care, Inc. 608 S. -

NORTH SHORE EVANSTON HOSPITAL Evanston, IL

NORTH SHORE EVANSTON HOSPITAL Evanston, IL PROGRAMS OFFERED NorthShore Evanston Hospital, a teaching affiliate of the University of Chicago Pritzker School of Medicine, offers fully accredited training in anatomic and clinical pathology for 12 residents as University of Chicago (NorthShore) Pathology (ACGME ID 300-16-21-412). The residency emphasizes thorough and balanced training in anatomic and clinical pathology. Trainees have opportunities and financial support for translational research and presentations at national meetings. Electives at the University of Chicago and other institutions are available. Residents also participate in a variety of professional activities in Chicago, such as meetings of local and national medical societies and symposia in the medical schools. All residents rotate at the Ann and Robert H. Lurie Children's Hospital of Chicago for pediatric pathology and the Office of the Medical Examiner of Cook County in Chicago for forensic pathology. REQUIREMENTS Applicants must be graduates of approved allopathic or osteopathic medical schools with minimum USMLE scores of 215 and COMLEX scores of 450 or above for Steps I and II, passing on the first attempt. Graduates of foreign medical schools must have a valid ECFMG certificate and be eligible for a J1 or H1-B visa. TYPES AND NUMBERS OF APPOINTMENTS We offer 12 accredited residency positions. Trainees generally choose a combined AP/CP experience. Fellowships in Medical Microbiology, Molecular Genetic Pathology, and Surgical Pathology are also offered. FACILITIES Headquartered in Evanston, Illinois, NorthShore University HealthSystem (NorthShore) is a fully integrated healthcare delivery system serving the Chicagoland area. The system includes four hospitals: Evanston Hospital in Evanston, Glenbrook Hospital in Glenview, Highland Park Hospital in Highland Park, and Skokie Hospital in Skokie, Illinois. -

Evanston Map M2

Be Ev Hil Ch Ev Hil Ev Th Ev Th Ev . EVANSTON MAP M2 ABCDEFGH I J KL shopping districts 1 LAKE AVE SHERIDAN RD ⅷA Downtown Evanston DOWNTOWN WILMETTE ⅷB Central Street ⅷC Chicago & Dempster 2 ⅷD Main & Chicago LINDEN AVE ⅷE Howard Street 3 WILMETTE AVE 14 attractions WILMETTE EVANSTON WILMETTE ૽1 Evanston Art Center COMMUNITY www.visitchicagonorthshore.com GOLF COURSE ૽2 Evanston History 4 SHERIDAN PL Center/Dawes House ISABELLA ST BROADWAY AVE BROADWAY ASBURY AVE ASBURY SHERIDAN RD ૽3 Frances E. Willard House THAYER ST JENKS ST GIRARD AVE WALNUT AVE WALNUT ૽4 Grosse Point Lighthouse PARK PL STEWART AVE 5 DR LINCOLNWOOD MONTICELLO ST HURD AVE RYAN FIELD EASTWOOD AVE EASTWOOD ૽5 HARTZEL ST MCGAW HALL CLINTON PL Mary & Leigh Block Museum of Art CENTRAL ST CENTRAL ST MARCY AVE MARCY CENTRAL PARK AVE 16 McDANIEL AVE McDANIEL B 1 LAKE HARRISON ST ૽6 Northwestern University 6 AVE EWING MILBURN ST 4 MICHIGAN BRYANT AVE BRYANT BENNETT AVE BENNETT PRAIRIE AVE LINCOLN ST ૽7 Noyes Cultural Center LINCOLN ST ૽8 COLFAX ST NOYES CT Rotary International PIONEER RD PIONEER COLFAX ST FORREST VIEW RD 7 Headquarters GRANT ST AVE WESLEY METRA 7 NOYES ST ૽9 Sigma Alpha Epsilon NOYES ST 6 ASHLAND AVE Levere Memorial Temple DEWEY AVE HAVEN ST GAFFIELD PL PAYNE ST NORTHWESTERN 8 15 GREEN BAY RD GARRETT PL recreation SIMPSON ST UNIVERSITY ᮡ RIDGE AVE RIDGE 10 SIMPSON ST HAMLIN ST LIBRARY PL Burnham Shore Park WOODLAND RD CORMICK BLVD Dempster Street Beach GOLF MC FOSTER ST 9 SHERMAN Aquatic Center CTA LAUREL AVE LAUREL MAPLE ᮡ EMERSON ST 11 Centennial Park -

Service Area Map.Pdf

North Shore Water Reclamation District Service Area Map Lake County, Illinois January 2015 George Lake L a k e C s Camp Lake h o k r o e ro Paasch Lake b g W 1 n h 31 i t C VU r s p 9 t 114th Voltz Lake V S 3 116th # Lake Shangri La and Benet Lake 1 Rock Lake 1 Mud Lake h Peat Lake t 0 Cross Lake 1 Russell 2 Russel y Russell n y a Antioch STP l e e n # D a Catherine, Lake Deer Lake l e Antioch D 41 VU173 ¤£ Silver Lake Sterling Lake e k Antioch Lake a L VU59 p Bluff Lake e e d r D o f w a y East Loon Lake White Lake Huntley Lake r Zion n C a Loon Lake l ! e Elmwood Farms Lake D Turner Lake Grass Lake Kelly Lindenhurst STP 29th Fox Lake # Potomac, Lake Wadsworth Petite Lake Sun Lake Waterford Lake Mill Creek STP Dunns Lake Hastings Lake Wadsworth Beach Park Deep Lake Crooked Lake ! Cedar Lake Lake Linden Lindenhurst # ! ¤£45 VU132 ! Sand Lake Sand Lake H Yorkhouse u tc Dead Lake h Slough Lake in s Fox Lake Miltmore Lake Ste VU132 Monaville arns School Fox VUL59ake STP Sunset Ro Fourth Lake llin Grandwood Lake # s n o G s o l i lf VU131 W L akes s hore Rollin Waukegan WRF VU59 Duck Lake Long Lake Round Lake Beach Lake Shore ! Gurnee VU137 # e Waukegan k ! a ! VU173 L Third Lake VU132 132 VU s r 134 i VU a Druce Lake w d Brandenburg Lake e e Wooster Lake Washington L C s Bay i Gurnee WRF o # n Highland Lake i l l I Round Lake f a Camp Hickory STP e # l n Cranberry Lake Gages Lake e e Nippersink Gages Lake ! r Grayslake G ! Valley Lake Lake Michigan e 10th Grays Lake n Sullivan Lake i a l p O Fish Lake r e v i R U120 Lily Lake V y n d l a -

2014–2015 Community Benefits Report

2014–2015 Community Benefits Report The more NorthShore University HealthSystem and the community connect, the stronger and healthier both will become. Participants in the Be Well-Lake County diabetes management program plant vegetables at the North Chicago Community Garden. Be Well is a partnership between NorthShore University HealthSystem and the Lake County Health Department and Community Health Center. See page 6 for more about the program. At NorthShore University HealthSystem (NorthShore), we believe in serving and investing in the health and well-being of people who live in our communities. Whether it is care for the medically underserved, medication assistance, perinatal services or specialized programs—NorthShore’s commitment to the community is demonstrated every day in many ways. NorthShore Mission NorthShore’s core mission is “to preserve and improve human life.” This mission will be achieved through the provision of superior clinical care, Statement academic excellence and innovative research. NorthShore is a not-for-profit organization principally formed to provide quality healthcare services for the communities it serves. The delivery of healthcare services is provided in a wide range of inpatient and ambulatory healthcare settings, community- wide, employing modern technology and expertise. Support for qualified patients who may not be able to pay the entire cost of their care is part of the organization’s commitment. In support of its primary mission of patient care, the organization engages in a wide range of academic activities in medical education and research. This statement recognizes the Board of Directors’ responsibility to maintain the organization’s viability to meet its long-term commitment to the communities it serves. -

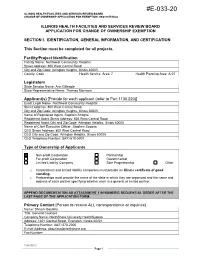

E-033-20 ILLINOIS HEALTH FACILITIES and SERVICES REVIEW BOARD CHANGE of OWNERSHIP APPLICATION for EXEMPTION- 09/2019 Edition

#E-033-20 ILLINOIS HEALTH FACILITIES AND SERVICES REVIEW BOARD CHANGE OF OWNERSHIP APPLICATION FOR EXEMPTION- 09/2019 Edition ILLINOIS HEALTH FACILITIES AND SERVICES REVIEW BOARD APPLICATION FOR CHANGE OF OWNERSHIP EXEMPTION SECTION I. IDENTIFICATION, GENERAL INFORMATION, AND CERTIFICATION This Section must be completed for all projects. Facility/Project Identification Facility Name: Northwest Community Hospital Street Address: 800 West Central Road City and Zip Code: Arlington Heights, Illinois 60005 County: Cook Health Service Area: 7 Health Planning Area: A-07 Legislators State Senator Name: Ann Gillespie State Representative Name: Thomas Morrison Applicant(s) [Provide for each applicant (refer to Part 1130.220)] Exact Legal Name: Northwest Community Hospital Street Address: 800 West Central Road City and Zip Code: Arlington Heights, Illinois 60005 Name of Registered Agent: Stephen Scogna Registered Agent Street Address: 800 West Central Road Registered Agent City and Zip Code: Arlington Heights, Illinois 60005 Name of Chief Executive Officer: Stephen Scogna CEO Street Address: 800 West Central Road CEO City and Zip Code: Arlington Heights, Illinois 60005 CEO Telephone Number: (847) 618-5007 Type of Ownership of Applicants Non-profit Corporation Partnership For-profit Corporation Governmental Limited Liability Company Sole Proprietorship Other o Corporations and limited liability companies must provide an Illinois certificate of good standing. o Partnerships must provide the name of the state in which they are organized and the name -

Community Health Needs Assessment 2019

Evanston Hospital | Glenbrook Hospital | Highland Park Hospital | Skokie Hospital Community Health Needs Assessment 2019 NorthShore University HealthSystem Acknowledgements The community health needs assessment (CHNA) for NorthShore University HealthSystem (NorthShore) supports the organization’s mission to “preserve and improve human life.” This community health needs assessment was made possible because of the commitment toward addressing the health needs in the community. Many individuals across the organization devoted time and resources to the completion of this assessment. NorthShore would like to thank leaders from the following community organizations who participated in focus groups and interviews and provided valuable information to be used in the assessment: City of Evanston-Department of Health Moraine Township CJE Senior Life NAMI Cook County North Suburban Deerfield Parent Network Niles Township High School District 219 Erie Family Health Center Northbrook Chamber of Commerce Evanston Fire Department Northfield Township Evanston/Skokie School District 65 Northwest Suburban United Way Faith in Action Peer Services Family Services of Glencoe Skokie Police Department Frisbie Senior Center St. Philip Lutheran Church Glenbrook South High School Terry Performance Group Glenview Chamber of Commerce Tri-Con Child Care Center Great Lakes Adaptive Sports Association Turning Point Behavioral Health Lake County Health Department Village of Glenview McGaw YMCA Village of Skokie, Health Department This CHNA has been facilitated by Crowe LLP (“Crowe”). Crowe is one of the largest public accounting, consulting, and technology firms in the United States. Crowe has significant healthcare experience including providing services to hundreds of large healthcare organizations across the country. For more information about Crowe’s healthcare expertise visit www.crowe.com/industries/healthcare. -

Northshore Council of Mayors Management Monitoring Schedule FY 2022-2027 Proposed Highway Improvement Program

NORTHWEST MUNICIPAL CONFERENCE 1600 East Golf Road, Suite 0700 A Regional Association of Illinois Des Plaines, Illinois 60016 Municipalities and Townships Representing a Population of Over One Million (847) 296-9200 Fax (847) 296-9207 www.nwmc-cog.org MEMBERS North Shore Council of Mayors Antioch Arlington Heights Technical Committee Meeting Bannockburn Thursday, July 15, 2021 Barrington Bartlett 8:30 a.m. Buffalo Grove Via Zoom Video Conference Deer Park Deerfield https://us02web.zoom.us/j/83082897682?pwd=VkFLWGttTEJKOTMvcE14TG9KVGduZz09 Des Plaines Elk Grove Village Evanston AMENDED AGENDA Fox Lake Glencoe Glenview I. Call to Order Grayslake Hanover Park Highland Park II. Approval of Meeting Minutes – April 15, 2021 (Attachment A) Hoffman Estates Action Requested: Approval Kenilworth Lake Bluff Lake Forest III. Agency Reports Lake Zurich Libertyville a. Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning (Attachment B) Lincolnshire b. IDOT Local Roads Update (Attachment C) Lincolnwood Morton Grove c. IDOT Highways Report (Attachment D) Mount Prospect d. Illinois Tollway Niles Northbrook e. Metra (Attachment E) Northfield f. Pace (Attachment F) Northfield Township Palatine g. Cook County Department of Transportation and Highways Park Ridge Action Requested: Informational Prospect Heights Rolling Meadows Schaumburg IV. North Shore Council of Mayors Surface Transportation Program (STP) Skokie Streamwood a. Local Surface Transportation Program (STP-L) Update (Attachment G) Vernon Hills Staff will present an updated status sheet for the FFY 2021-2025 program West Dundee and highlight the changes that were made. Wheeling Wilmette Action Requested: Informational Winnetka b. Cost Increase Request – Village of Morton Grove (Attachment H) President The Village of Morton Grove is requesting a cost increase of $44,925 STP-L Nancy Rotering funding for Phase II engineering for their Austin/Oakton Intersection project. -

Wintrust.Com/Findus

TO FIND THE LOCATION AND FREE ATM CLOSEST TO YOU, VISIT: OUR COMMUNITY BANK LOCATIONS BY CITY wintrust.com/findus MORE THAN WHEATON BURLINGTON LAKE GENEVA MONROE Wheaton Bank & Trust Town Bank Town Bank Town Bank 72 OVER 370 S. County Farm Rd. 100 E. Washington St. 550 Commercial Ct. 101 7 1/2 St. BANK 175 4,000 Wheaton, IL 60187 Burlington, WI 53105 Lake Geneva, WI 53147 Monroe, WI 53566 LOCATIONS EMPLOYEES 630-407-0900 262-767-3283 262-248-5189 608-328-3800 BRANDS WILLOWBROOK 400 Milwaukee Ave. 567 Broad St. PEWAUKEE Community Bank of Willowbrook Burlington, WI 53105 Lake Geneva, WI 53147 Town Bank ILLINOIS BLOOMINGDALE Wintrust Bank - Delaware Place Wintrust Bank - Oak & Rush 6262 S. Route 83 262-763-3581 262-248-6940 N35 W23877 Highfield Ct., Bloomingdale Bank & Trust 190 E. Delaware Pl. 1000 N. Rush St. Willowbrook, IL 60527 Ste. 100 ADDISON 165 W. Lake St. Chicago, IL 60611 Chicago, IL 60611 630-920-2700 CLINTON MADISON Pewaukee, WI 53072 Addison Bank & Trust Bloomingdale, IL 60108 312-280-0360 312-440-4000 Town Bank Town Bank 262-691-9400 114 E. Lake St. 630-295-9111 WILMETTE 501 Ogden Ave. 10 W. Mifflin St. Addison, IL 60101 Wintrust Bank - Fulton Market Wintrust Bank - Old Town North Shore Community Clinton, WI 53525 Madison, WI 53703 RACINE 630-607-7760 BOLINGBROOK 801 W. Fulton Market 100 W. North Ave. Bank & Trust 608-676-4700 608-282-4840 Town Bank Bolingbrook Bank & Trust Chicago, IL 60607 Chicago, IL 60610 1145 Wilmette Ave. 5005 Washington Ave. ALGONQUIN 198 S. -

The Art of Craft the 35Th Annual American Craft Exposition Show This Month Wilmette’S Actors Supports Access to Mental Health Care

SATURDAY SEPTEMBER 7 | SUNDAY SEPTEMBER 8 2019 FIND US ONLINE: DailyNorthShore.com SPORTS SOCIAL SUNDAY Loyola Academy’s Spencer SCENE BREAKFAST Werner churns to distance The Gallery in Lake Paula Danoff gets hall of double at Junior Olympics. Forest hosts local fame distinction. P18 P17 artists. P10 NO. 360 | A JWC MEDIA PUBLICATION FOLLOW US: NEWS Top Props THE ART OF CRAFT THE 35TH ANNUAL AMERICAN CRAFT EXPOSITION SHOW THIS MONTH WILMETTE’S ACTORS SUPPORTS ACCESS TO MENTAL HEALTH CARE. TRAINING CENTER IS HONORED ON THE RED diagnosed with kidney disease. BY MONICA KASS ROGERS It was Miller’s memories of the CARPET. THE NORTH SHORE WEEKEND pleasure that early adventures in wood- working brought that sent him back EDITED BY SHERRY THOMAS The morning light filtering in from to the tool bench, helping him segue THE NORTH SHORE WEEKEND the front window at Jeff Miller’s hand- to the new form of artistic expression crafted furniture gallery is soft—soft that would become his life’s work. as the finish and gentle curves that “With music, you’ve got a bunch of Carole Dibo, founder of Actors Training Center beckon from the designer craftsman’s notes on a page that tell you what you (ATC) of Wilmette, took to the stage on August elegant chairs. are supposed to play, but that’s the 24 to accept Illinois Theatre Association’s (ITA) Each was born of a constellation of merest beginning of what makes a 2019 Award of Honor inspirations that Miller has drawn beautiful composition. It’s very much “It is true that we “train to work,” but we do it from for 35 years, creating furnishings the same with furniture,” he says. -

Area Lodging Summer Festivals

Chicago’s North Shore Bahá’í House of Worship, one of the Seven Wonders of Illinois, 2007 Kohl Children’s Museum Bordering Chicago, along the glorious shores of Lake Michigan, the inviting communities of Evanston, Skokie, Glenview, Wilmette and Northbrook are just twenty minutes north of Chicago’s city center and truly offer something for everyone! During your North Shore visit, you can stroll through Northwestern University’s ivy-lined campus. If you continue north, do so by taking a relaxing drive along the region’s famed Sheridan Road, which actually hugs the lakefront. This gorgeous, winding stretch of road offers the most spectacular views of gracious homes, famed architecture, and the bounty of nature. Make a point to see Wilmette’s Bahá’í House of Worship, an architectural wonder, and take a tour of Wilmette’s Historical Homes on a walking tour or visit the Chicago Botanic Garden where you can explore dozens of natural gardens from the brightly colored Chicago Botanic Garden whimsical to the peaceful, subtle and serene. If you’re in town with children, you won’t want to miss The last sentence on the first page should read the Skokie Northshore Sculpture Park and Wagner Farm. brought to you by Lots to See and Do Summer Festivals JUNE 16 & 17 Custer’s Last Stand Arts & Crafts Fair Custer Ave. & Washington St. • Evanston 847.328.2204 • www.custerfair.com 23 & 24 Fountain Square Arts Festival Church St. & Sherman Ave. • Evanston 773.868.3010 • www.chicagospecialevents.com Westfield Old Orchard 30 Glenview Summer Festival If shopping is your passion Chicago’s North Shore is Glenview Rd.