Internal State Dependent Odor Processing and Perception—The Role of Neuromodulation in the Fly Olfactory System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Welcome to the New Open Access Neurosci

Editorial Welcome to the New Open Access NeuroSci Lucilla Parnetti 1,* , Jonathon Reay 2, Giuseppina Martella 3 , Rosario Francesco Donato 4 , Maurizio Memo 5, Ruth Morona 6, Frank Schubert 7 and Ana Adan 8,9 1 Centro Disturbi della Memoria, Laboratorio di Neurochimica Clinica, Clinica Neurologica, Università di Perugia, 06132 Perugia, Italy 2 Department of Psychology, Teesside University, Victoria, Victoria Rd, Middlesbrough TS3 6DR, UK; [email protected] 3 Laboratory of Neurophysiology and Plasticity, Fondazione Santa Lucia, and University of Rome Tor Vergata, 00143 Rome, Italy; [email protected] 4 Department of Experimental Medicine, University of Perugia, 06132 Perugia, Italy; [email protected] 5 Department of Molecular and Translational Medicine, University of Brescia, 25123 Brescia, Italy; [email protected] 6 Department of Cell Biology, School of Biology, University Complutense of Madrid, Av. Jose Antonio Novais 12, 28040 Madrid, Spain; [email protected] 7 School of Biological Sciences, University of Portsmouth, Hampshire PO1 2DY, UK; [email protected] 8 Department of Clinical Psychology and Psychobiology, University of Barcelona, 08035 Barcelona, Spain; [email protected] 9 Institute of Neurosciences, University of Barcelona, 08035 Barcelona, Spain * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 6 August 2020; Accepted: 17 August 2020; Published: 3 September 2020 Message from Editor-in-Chief: Prof. Dr. Lucilla Parnetti With sincere satisfaction and pride, I present to you the new journal, NeuroSci, for which I am pleased to serve as editor-in-chief. To date, the world of neurology has been rapidly advancing, NeuroSci is a cross-disciplinary, open-access journal that offers an opportunity for presentation of novel data in the field of neurology and covers a broad spectrum of areas including neuroanatomy, neurophysiology, neuropharmacology, clinical research and clinical trials, molecular and cellular neuroscience, neuropsychology, cognitive and behavioral neuroscience, and computational neuroscience. -

The Creation of Neuroscience

The Creation of Neuroscience The Society for Neuroscience and the Quest for Disciplinary Unity 1969-1995 Introduction rom the molecular biology of a single neuron to the breathtakingly complex circuitry of the entire human nervous system, our understanding of the brain and how it works has undergone radical F changes over the past century. These advances have brought us tantalizingly closer to genu- inely mechanistic and scientifically rigorous explanations of how the brain’s roughly 100 billion neurons, interacting through trillions of synaptic connections, function both as single units and as larger ensem- bles. The professional field of neuroscience, in keeping pace with these important scientific develop- ments, has dramatically reshaped the organization of biological sciences across the globe over the last 50 years. Much like physics during its dominant era in the 1950s and 1960s, neuroscience has become the leading scientific discipline with regard to funding, numbers of scientists, and numbers of trainees. Furthermore, neuroscience as fact, explanation, and myth has just as dramatically redrawn our cultural landscape and redefined how Western popular culture understands who we are as individuals. In the 1950s, especially in the United States, Freud and his successors stood at the center of all cultural expla- nations for psychological suffering. In the new millennium, we perceive such suffering as erupting no longer from a repressed unconscious but, instead, from a pathophysiology rooted in and caused by brain abnormalities and dysfunctions. Indeed, the normal as well as the pathological have become thoroughly neurobiological in the last several decades. In the process, entirely new vistas have opened up in fields ranging from neuroeconomics and neurophilosophy to consumer products, as exemplified by an entire line of soft drinks advertised as offering “neuro” benefits. -

Glutamatergic Synaptic Plasticity in the Mesocorticolimbic System in Addiction

REVIEW ARTICLE published: 20 January 2015 CELLULAR NEUROSCIENCE doi: 10.3389/fncel.2014.00466 Glutamatergic synaptic plasticity in the mesocorticolimbic system in addiction Aile N. van Huijstee and Huibert D. Mansvelder * Department of Integrative Neurophysiology, Center for Neurogenomics and Cognitive Research, Neuroscience Campus Amsterdam, VU University Amsterdam, Amsterdam, Netherlands Edited by: Addictive drugs remodel the brain’s reward circuitry, the mesocorticolimbic dopamine (DA) Arianna Maffei, SUNY Stony Brook, system, by inducing widespread adaptations of glutamatergic synapses. This drug-induced USA synaptic plasticity is thought to contribute to both the development and the persistence Reviewed by: Christian Luscher, Geneva of addiction. This review highlights the synaptic modifications that are induced by in vivo University Hospital, University of exposure to addictive drugs and describes how these drug-induced synaptic changes may Geneva, Switzerland contribute to the different components of addictive behavior, such as compulsive drug Fereshteh S. Nugent, Uniformed use despite negative consequences and relapse. Initially, exposure to an addictive drug Services University, USA induces synaptic changes in the ventral tegmental area (VTA). This drug-induced synaptic *Correspondence: Huibert D. Mansvelder, Department potentiation in the VTA subsequently triggers synaptic changes in downstream areas of of Integrative Neurophysiology, the mesocorticolimbic system, such as the nucleus accumbens (NAc) and the prefrontal Center -

Neurobiology and Behavior (NEURBIO) 1

Neurobiology and Behavior (NEURBIO) 1 Neurobiology and Behavior (NEURBIO) Courses NEURBIO 200A. Research in Neurobiology and Behavior. 2-12 Units. Individual research with Neurobiology and Behavior faculty. Repeatability: Unlimited as topics vary. Restriction: Graduate students only. Neurobiology and Behavior Majors only. NEURBIO 200B. Research in Neurobiology and Behavior. 2-12 Units. Individual research with Neurobiology and Behavior faculty. Prerequisite: NEURBIO 200A Repeatability: Unlimited as topics vary. Restriction: Graduate students only. Neurobiology and Behavior Majors only. NEURBIO 200C. Research in Neurobiology and Behavior. 2-12 Units. Individual research with Neurobiology and Behavior faculty. Prerequisite: NEURBIO 200B Repeatability: Unlimited as topics vary. Restriction: Graduate students only. Neurobiology and Behavior Majors only. NEURBIO 201A. Research in Neurobiology and Behavior. 2-12 Units. Individual research with Neurobiology and Behavior faculty. Grading Option: Satisfactory/unsatisfactory only. Repeatability: Unlimited as topics vary. Restriction: Graduate students only. Neurobiology and Behavior Majors only. NEURBIO 201B. Research in Neurobiology and Behavior. 2-12 Units. Individual research with Neurobiology and Behavior faculty. Prerequisite: NEURBIO 201A Grading Option: Satisfactory/unsatisfactory only. Repeatability: Unlimited as topics vary. Restriction: Graduate students only. Neurobiology and Behavior Majors only. NEURBIO 201C. Research in Neurobiology and Behavior. 2-12 Units. Individual research with Neurobiology and Behavior faculty. Prerequisite: NEURBIO 201B Grading Option: Satisfactory/unsatisfactory only. Repeatability: Unlimited as topics vary. Restriction: Graduate students only. Neurobiology and Behavior Majors only. NEURBIO 202A. Foundations of Neuroscience. 2 Units. Intended to expose students to critical reading and analysis of the primary neuroscience literature. Instructors from departments associated with the Interdepartmental Neuroscience Program participate and discuss topics of current interest. -

Neuroscience Major Requirements (Fall 2017 Or Later)

Neuroscience Major Requirements (Fall 2017 or later) Undergraduate Program in Neuroscience : 1140 Undergrad. Science Bldg. (USB) : http://www.lsa.umich.edu/neurosci : [email protected] : 734-763-7984 (front desk) Why study Neuroscience? Neuroscience is the study of the nervous system. Neuroscientists aim to understand how the nervous system develops and functions on a cellular level as well as the mechanisms that underlie behavior, mental disorders and disease. The faculty teaching courses in the major include cellular and molecular neuroscientists appointed in the Department of Molecular, Cellular and Developmental Biology (MCDB) and behavioral and cognitive neuroscientists appointed in the Department of Psychology. This interdisciplinary program gives students the best of both of these worlds. Who should major in Neuroscience? Any student who wishes to pursue a career studying the nervous system or behavior. This is an excellent major for anyone interested in pre-health careers, graduate studies, or careers in the biotech industry. Exclusions: Students who elect a major in Neuroscience may not elect the following majors: Biochemistry Biology Biology, Health & Society (BHS) Biomolecular Science (BMS) Biopsychology, Cognition and Neuroscience (BCN) Cellular & Molecular Biology (CMB) CMBS (formerly CMB:BME) Molecular, Cellular, and Developmental Biology (MCDB) Microbiology Plant Biology Students who elect a major in Neuroscience may not elect a minor in Biology, Plant Biology, Chemistry, or Biochemistry. Students can double major in Psychology and Neuroscience or Cognitive Science and Neuroscience, but may only share a maximum of 3 courses between their two programs. How do I declare? Students interested in neuroscience are encouraged to meet with an advisor to discuss their academic plans as soon as possible! Students need not have completed all of the prerequisites of the major to declare, but should usually have completed the biology introductory sequence with a 2.0 or better and be in good academic standing. -

Neuromodulation Shapes Interneuron Communication in the Mouse Striatum

From DEPARTMENT OF NEUROSCIENCE Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden NEUROMODULATION SHAPES INTERNEURON COMMUNICATION IN THE MOUSE STRIATUM Matthijs Constantijn Dorst Stockholm 2020 All previously published papers were reproduced with permission from the publisher. Published by Karolinska Institutet. Printed by US-AB © Matthijs Constantijn Dorst, 2020 ISBN 978-91-7831-908-4 Neuromodulation shapes interneuron communication in the mouse Striatum THESIS FOR DOCTORAL DEGREE (Ph.D.) By Matthijs Constantijn Dorst Principal Supervisor: Opponent: Professor Gilad Silberberg Professor Hagai Bergman Karolinska Institutet The Hebrew University of Jerusalem Department of Neuroscience Edmond & Lily Safra Center for Brain Sciences Co-supervisor(s): Examination Board: Professor Per Uhlén Professor Per Svenningsson Karolinska Institutet Karolinska Institutet Department of Medical Biochemistry and Department of Clinical Neuroscience Biophysics Division of Neuropharmacology - movement disorders Senior lecturer Karima Chergui Karolinska Institutet Department of Physiology and Pharmacology Division of Molecular Neurophysiology Professor Klas Kullander Uppsala Universitet Department of Neuroscience Research group Formation and Function of Neuronal Circuits Included Studies The following studies are included in this thesis, and will be referenced through- out the text as such: Study 1 Garas, F.N., Shah, R.S., Kormann, E., Doig, N.M., Vinciati, F., Nakamura, K.C., Dorst, M.C., Smith, Y., Magill, P.J. and Sharott, A., 2016. Sec- retagogin expression delineates functionally-specialized populations of striatal parvalbumin-containing interneurons. Elife, 5, p.e16088. Study 2 Lindroos, R., Dorst, M.C., Du, K., Filipović, M., Keller, D., Ketzef, M., Kozlov, A.K., Kumar, A., Lindahl, M., Nair, A.G., Pérez-Fernández, J., Grillner, S., Silberberg, G., Kotaleski, J.H., 2018. Basal Ganglia Neuromodulation Over Multiple Temporal and Structural Scales—Simulations of Direct Pathway MSNs Investigate the Fast Onset of Dopaminergic Effects and Predict the Role of Kv4. -

Dan Zekzer, M

SHOSHANA EITAN, PH.D. ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR Behavioral and Cellular Neuroscience • Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences Texas A&M University • College Station, TX 77843 Positions and Employment: 1997-2000 Trainee, Norman Cousin Center of Psychoneuroimmunology, UCLA, Los Angeles, CA - Rothschild Foundation Scholar 2000-2002 Post-Doctoral Fellow, Neuropsychiatric Institute, UCLA, Los Angeles, CA 2002-2005 Assistant Researcher, Neuropsychiatric Institute, UCLA, Los Angeles, CA 2005-2013 Assistant Professor, Behavioral and Cellular Neuroscience, Department of Psychology, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 2008-present Faculty Member, Texas A&M Institute for Neuroscience (TAMIN), College Station, TX 2013-2017 Associate Professor, Behavioral and Cellular Neuroscience, Department of Psychology, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 2017-present Associate Professor, Behavioral and Cellular Neuroscience, Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX Education: 1997 Ph.D. in Neurobiology, Clore Distinguished Scholar, Neurobiology Department, Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot, Israel – Clore Distinguished Scholar for Graduate Students 1992 M.Sc. in Neurobiology, Neurobiology Department, Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot, Israel – Wolf Prize Award for Master Students 1990 B.A. in Biology, Open University, Tel-Aviv, Israel Professional Experiences and Memberships: 1992- present Society of Neuroscience 2005- present Society of Neuroscience, Texas A&M chapter 2005- present Member of the Graduate Faculty at Texas A&M University 2008- present Faculty of Neuroscience, Texas A&M Institute for Neuroscience 2009 Texas A&M-CONACYT: Collaborative Research Grant Program Review Committee 2013-present Editorial Board member, Pain Studies and Treatment (PST) 2014-15 PESCA Peer Review Committee Research Interests: I. Understanding the effects of psychosocial environment and stress on drug abuse, with specific focus on the vulnerabilities of adolescents to opioid abuse. -

Regional Complexity in Enteric Neuron Wiring Reflects Diversity of Motility

RESEARCH ARTICLE Regional complexity in enteric neuron wiring reflects diversity of motility patterns in the mouse large intestine Zhiling Li1, Marlene M Hao2, Chris Van den Haute3,4, Veerle Baekelandt3, Werend Boesmans1,5,6*, Pieter Vanden Berghe1* 1Laboratory for Enteric NeuroScience (LENS), Translational Research Center for Gastrointestinal Disorders (TARGID), University of Leuven, Leuven, Belgium; 2Department of Anatomy and Neuroscience, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia; 3Laboratory for Neurobiology and Gene Therapy, Department of Neurosciences, KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium; 4Leuven Viral Vector Core, KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium; 5Department of Pathology, GROW-School for Oncology and Developmental Biology, Maastricht University Medical Center, Maastricht, The Netherlands; 6Biomedical Research Institute (BIOMED), Hasselt University, Hasselt, Belgium Abstract The enteric nervous system controls a variety of gastrointestinal functions including intestinal motility. The minimal neuronal circuit necessary to direct peristalsis is well-characterized but several intestinal regions display also other motility patterns for which the underlying circuits and connectivity schemes that coordinate the transition between those patterns are poorly understood. We investigated whether in regions with a richer palette of motility patterns, the underlying nerve circuits reflect this complexity. Using Ca2+ imaging, we determined the location *For correspondence: and response fingerprint of large populations of enteric neurons upon focal network -

Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences

DEPARTMENT OF BRAIN AND COGNITIVE SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF BRAIN AND COGNITIVE mathematics, or computer science, depending on the individual SCIENCES student's research program. Graduate students begin a research apprenticeship immediately upon arrival with lab rotations in the rst year, aer which time advisor choices are made based upon a match of interests. These Graduate Study assignments may change as a student's goals become more focused. The Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences oers programs of At the end of the rst year, an advisory committee of two to four study leading to the doctoral degree in neuroscience or cognitive faculty members is formed. This committee monitors progress and, science. Areas of research specialization include cellular and with membership changing as necessary, evolves into the thesis molecular neuroscience, systems neuroscience, computation, and committee. Thesis research normally requires 24-48 months of full- cognitive science. The graduate programs are designed to prepare time activity aer the qualifying examinations have been passed. It students to pursue careers in research, teaching, or industry. is expected that the research embodied in the PhD dissertation be original and signicant work, publishable in scientic journals. Doctor of Philosophy The departmental PhD program can normally be completed with Financial Support four to six years of full-time work, including summers. Institute Financial assistance is provided to qualied applicants in the form requirements for the PhD are given in the section on General Degree of traineeships, research assistantships, teaching assistantships, Requirements (http://catalog.mit.edu/mit/graduate-education/ and a limited number of fellowships, subject to availability of general-degree-requirements). -

Unifed Double Major in Psychology and Biological Sciences

Bachelor of Science in Neuroscience Concentrations in Cognitive Neuroscience, Neurobiology or Computational Neuroscience The Dietrich College of Humanities & Social Sciences and the Mellon College of Science have joined forces to establish an interdisciplinary program leading to a Bachelor of Science in Neuroscience. Students will gain a broad understanding of Neuroscience at many different levels of analysis, including cellular biology of the brain, brain systems, cognitive brain function, and computational brain modeling. Students will need to complete one of the three concentrations: Cognitive Neuroscience, Neurobiology or Computational Neuroscience. Students may only double count 3 courses from the Core Neuroscience courses and concentration area of the major with another major or minor. If you have problems scheduling or course requirements, please reach out to Emilie O’Leary [email protected]. Please contact Emilie O’Leary ([email protected]) or Dr. Erik Thiessen ([email protected]) with further questions. General Science Requirements Core Neuroscience Courses 21-120 Differential & Integral Calculus 85-219 Biological Foundations of Behavior 21-122 Integration & Approximation Or 03-161 Molecules to Mind Or 21-124 Calculus II for Biologists and Chemists 85-211 Cognitive Psychology Or 85-213 Human Information Processing and AI 03-121 Modern Biology 03-220 Genetics 03-362 Cellular Neuroscience 33-111 Physics 1 for Science Students 03-363 Systems Neuroscience Or 33-141 Physics for Engineering Students 85-419 Intro to -

Development of Enteric Neurons and Muscularis Macrophages Marina Avetisyan Washington University in St

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations Arts & Sciences Spring 5-15-2019 Development of Enteric Neurons and Muscularis Macrophages Marina Avetisyan Washington University in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/art_sci_etds Part of the Allergy and Immunology Commons, Immunology and Infectious Disease Commons, Medical Immunology Commons, and the Neuroscience and Neurobiology Commons Recommended Citation Avetisyan, Marina, "Development of Enteric Neurons and Muscularis Macrophages" (2019). Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1781. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/art_sci_etds/1781 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Arts & Sciences at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS Division of Biology and Biomedical Sciences Neurosciences Dissertation Examination Committee: Robert O. Heuckeroth, Chair Aaron DiAntonio, Co-Chair Paul Bridgman Joseph Dougherty Kelly Monk Development of Enteric Neurons and Muscularis Macrophages. by Marina Avetisyan A dissertation presented to The Graduate School of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2019 St. Louis, -

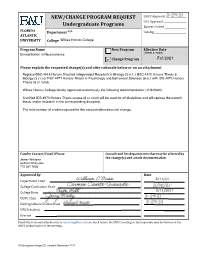

NEW/CHANGE PROGRAM REQUEST Undergraduate Programs

NEW/CHANGE PROGRAM REQUEST UUPC Approval _________________ UFS Approval ___________________ Undergraduate Programs Banner Posted __________________ FLORIDA Department Catalog __________________________ ATLANTIC UNIVERSITY College Program Name New Program Effective Date (TERM & YEAR) Change Program Please explain the requested change(s) and offer rationale below or on an attachment Faculty Contact/Email/Phone Consult and list departments that may be affected by the change(s) and attach documentation Approved by Date Department Chair College Curriculum Chair 3/14/21 College Dean UUPC Chair 3/12/2021 Undergraduate Studies Dean UFS President Provost Email this form and attachments to [email protected] one week before the UUPC meeting so that materials may be viewed on the UUPC website prior to the meeting. FAUprogramchangeUG, created December 2017 Concentration in Neuroscience There are two tracks: Track one: Cellular Neuroscience Track Two: Neuroscience, Cognition, and Behavior Track one Neuroscience - Cellular Neuroscience Required courses Course# Course Title Credits NEURO CORE PSY 1012 Honors General Psychology 3 BSC 1010 Honors Biological Principles 3 BSC 1010L Honors Biological Principles Lab 1 PCB 3703 Honors Human Morphology 1 3 PCB 3703L Honors Morphology and Function 1 Lab 1 CHM 2045 Honors General Chemistry 1 3 CHM 2045L Honors General Chemistry 1 Lab 1 CHM 2046 Honors General Chemistry 2 3 CHM 2046L Honors General Chemistry 2 Lab 1 STA 2023 Honors Statistics 3 BSC 4915* Honors Research in Biology 3 BSC 4970* IDS 4970 RI: Honors